Oral Cancer: Prevention, Management, and Treatment

Oral cancer can occur in any part of the oral cavity, including the lips and oropharynx. This chapter will focus on the identification, management, and treatment of oral cancer and the means of preventing it from occurring. The causes of oral cancer will be reviewed with special emphasis on tobacco use. Systemic and oral effects of tobacco use, implications of tobacco use with regard to dental treatment planning, and tobacco cessation programs are also included in this chapter.

INCIDENCE AND PREVALENCE

In the United States, approximately two thirds of oral cancers occur in the oral cavity and one third in the oropharynx. The most common type of oral and oro-pharyngeal cancer is squamous cell carcinoma, accounting for about 9 out of every 10 oral malignancies. Other malignancies of the oral cavity include melanomas, lymphomas, sarcomas, and metastases from other areas of the body.

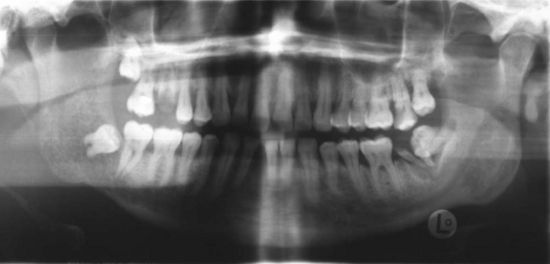

Metastasis to the oral region from a malignant tumor elsewhere in the body is rare, but those that occur are most often found in the mandible. Figure 11-1 is a radio-graph of cancer metastasis in the mandible. The majority of cancers found to have metastasized to the jaw are adenocarcinomas. The most common primary tumor sites with metastasis to the jaws are breast, lung, and kidney.1 See Table 11-1 for the relative frequency of metastatic lesions to the jaws.

Table 11-1

Relative Frequency of Origins of Metastasic Lesions in the Jaws

| Percent | |

| Breast | 30 |

| Lung | 20 |

| Kidney | 15 |

| Thyroid | 5 |

| Prostate | 5 |

| Colon | 5 |

| Stomach | 5 |

| Cutaneous melanoma | 5 |

Figure 11-1 Panoramic radiograph of a 48-year-old male smoker showing metastatic lung cancer to the right mandible.

The incidence of squamous cell carcinoma in the oral cavity, including the lips, differs by anatomic sites. Some sites seem to be relatively resistant, whereas other locations are particularly susceptible. In the past, when all anatomic sites were considered, the lower lip was cited as the most susceptible site, accounting for 30% to 40% of all oral squamous cell carcinomas. Data from the National Cancer Institute SEER (Surveillance, Epidemio-logy, and End Results) Program shows that in the last 10 years the incidence of squamous cell carcinoma of the lip has significantly decreased in the United States and is no longer the most prevalent oral site.1–3 Squamous cell carcinoma of the lip is still much more common in males than in females and occurs most commonly in individuals between the ages of 50 and 80 years old. Most of these lesions occur on either the right or left vermilion borders, seldom at the midline. Current statistics show that the highest incidence of oral squamous cell carcinoma is found at the lateral borders and the adjacent ventral surfaces of the tongue.

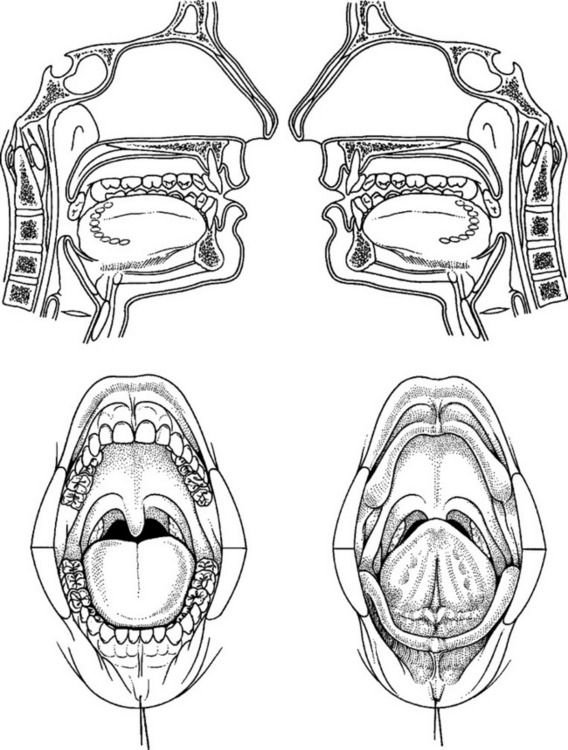

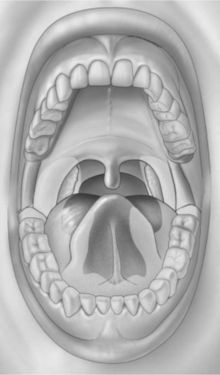

Intraoral squamous carcinoma lesions frequently form a horseshoe-shaped pattern as shown in Figure 11-2. The lateral and ventral surfaces of the tongue and the floor of the mouth are the most common sites. The soft palate and the lateral posterior regions adjacent to the anterior faucial pillars are the next most frequently seen sites for squamous cell carcinoma. Other areas less frequently affected are the gingiva and alveolar ridges, and the buccal mucosa. These areas combined account for less than 10% of oral squamous cell carcinomas.1

Figure 11-2 Horseshoe-shaped intraoral area most prone to the development of squamous cell carcinoma. It consists of the anterior floor of mouth, lateral borders of the tongue, tonsillar pillars, and lateral soft palate. (From Sapp JP, Eversole LR, Wysocki GP: Contemporary oral and maxillofacial pathology, ed 2, St Louis, 2004, Mosby.)

The incidence of oral cancer has remained at approximately 3% of all cancers in the United States. Approximately 30,000 new cases of oral and oropharyngeal cancer are diagnosed annually in men and women in the United States. About 95% of all oral cancers occur in persons over the age of 40.1–5 In the last decade, the ratio of male to female has been slightly less than 2 to 1. In the 1950s, this ratio was 6:1; this shift has been attributed to an increase in smoking by women.1,4

The total number of deaths annually attributed to oral and oropharyngeal cancer is as high as 7500 in the United States.3 Deaths caused by oral cancer represent approximately 2% of the total deaths caused by cancer in men and 1% in women. Although survival rates for most cancers have increased during the past several decades, there has been no such trend in the survival of patients with oral cancer. The overall 5-year survival rate of all patients with oral cancers has remained at about 50% over many decades. Approximately two thirds of all oral cancers are in the advanced stages (III or IV) at the time of diagnosis, decreasing the 5-year survival rate to 30%. Because 80% of early stage oral cancer (I or II) is localized, the cancer can be cured with appropriate treatment.2,5,6 Black males have the highest mortality from oral cancer when compared with other men of the same age.2,3,5 Genetics, education, socioeconomic status, and access to health care also seem to play a role in survival rates. The primary reason for the poor survival rate of individuals with oral cancer appears to be the result of the advanced stage of the cancer typically present at the initial diagnosis (See the What’s the Evidence? box on p. 276).1–3,6 The mortality statistics underline the importance of early detection and treatment for improving survival and the critical role played by the dental team.1,2,5,7

PROGNOSIS AND STAGING

As noted above, the prognosis for patients with oral cancer depends on the clinical stage of the tumor at the time of diagnosis. Staging is based on clinical findings: How large is the lesion? Has it spread to the lymph nodes? Has it metastasized? The abbreviations used in staging systems are TNM (tumor, nodes, and metastasis). See Table 11-2 for the TNM definitions and staging groups for the oral cavity. Staging is used in planning the treatment protocol for the cancer and in determining prognosis. For example, a patient with a stage I cancer might have a tumor of 2 cm or less with no palpable lymph nodes and no distant metastases. A patient with a cancer larger than 4 cm, palpable bilateral nodes, and with or without metastasis would be classified as a stage IV. As seen in Table 11-2, there can be many combinations that fall into the advanced stages III and IV. Oral cancers are initially staged based on clinical examination. The initial stage may change after findings from additional tests, imaging studies, and biopsy procedures. As a result, oral cancers that are first considered to be at stage I or II may be reclassified as stage III or IV if further information is obtained, showing, for example, tumor invasion into deeper structures, spread into lymph nodes, or distant metastases.1,2,6

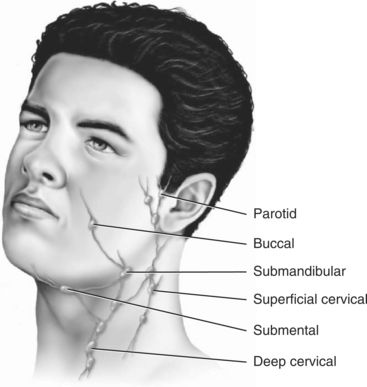

As the tumor grows, it may invade adjacent structures, such as the carotid artery sheath or neurovascular bundles. Squamous cell carcinomas of the oral cavity are known to spread by invading the lymphatic vessels. Once inside the lymphatic vessels, the tumor cells lodge and continue to proliferate in the regional lymph nodes. The lymph nodes most commonly invaded by intraoral squamous cell carcinoma are the submandibular and the superficial and deep cervical nodes. Squamous cell carcinomas of the lower lip metastasize first to the submental nodes and then may spread to the submandibular and the cervical lymph nodes. Tumor cells that spread beyond the regional lymph nodes of the head and neck often metastasize to the lungs, liver, and bone.1,2,6 Figure 11-3 provides a diagram of lymphatic drainage from oral cancers.

CAUSATION

The actual cause of oral cancers is not known. A number of causative factors have been speculated to contribute to the development of oral cancer (See the What’s the Evidence? box on p. 276). These factors include tobacco use, alcohol consumption, exposure to carcinogens and ultraviolet light (sun exposure), and gene mutation. Preexisting conditions, such as chronic candidiasis, viral infection (herpes simplex virus [HSV-1], human papillomavirus [HPV], human immunodeficiency virus [HIV], Epstein-Barr virus [EBV]), immunosuppression, and chronic irritation have also been implicated as risk factors.1,2,6 Poor dental health and poor nutritional status are often co-morbid factors in patients with oral cancer, but this as a causative factor has not been confirmed.2,4,6 Of all factors, tobacco use is regarded as the most important and is believed to contribute to the majority of oral cancers.4,6

Tobacco

The plant alkaloid nicotine, found in all forms of tobacco, is the psychoactive and addictive chemical agent, which in small quantities can have a profound effect on human physiology and psychology. This naturally occurring, plant-produced substance has many local and systemic toxic and physiologic effects (Table 11-3). When a small dose is delivered to the brain, nicotine can stimulate, relax, or induce a state of euphoria in the user. This psychoactive pleasurable perception is the primary reason for continuation and habituation of tobacco use. The longer an individual uses tobacco, the greater is the risk of developing dependence as a result of the effects of nicotine on the brain.

Table 11-3

Pathophysiologic Effects of Nicotine

| Effect on Cells and Cellular Functions | Effect on Oral Environment |

| Inhibition of fibroblast function | Poor wound healing |

| Increased collagenase function | Increased periodontal disease |

| Increased inflammatory response | Vasoconstriction |

| Impaired cellular immunity (chemotaxic function of macrophages and polymorphonuclear leukocytes [PMNs]) | Increased risk of infection |

| Impaired humoral immunity (decreased salivary and serum antibodies) | Quantitative and qualitative decrease in salivary secretions |

Initiation in the use of tobacco and progression to nicotine addiction is influenced by sociocultural, psychological, physiologic, and genetic factors.8 Chronic tobacco use is characterized by psychological (habituation, behavioral) and pharmacologic (addiction, chemical dependency) factors. Because tobacco use may decrease appetite and increase the user’s basal metabolic rate, some smokers may use tobacco as a weight management strategy. Both male and female smokers may experience a weight gain of 5 to 10 lb upon smoking cessation, a frequently cited justification for not quitting.9 The health risks of continued smoking are far greater than the health benefit of avoiding a 5 to 10 lb weight gain,10 but unfortunately in the mind of the continuing tobacco user, the psychosocial reinforcement associated with preventing weight gain and the concurrent psychological pleasure of tobacco use may outweigh the obvious health benefits of smoking cessation.

Tobacco can cause oral cancer in multiple ways. There are 43 identified carcinogens in tobacco smoke and 28 in smokeless tobacco.11,12 The effects of these agents at the cellular and DNA levels are profound and continue to be better understood. Chemical components in tobacco products, and heat generated by smoked tobacco act as direct physical irritants to the oral tissue. Some forms of smokeless tobacco contain a gritty additive that, by intent, abrades and creates microscopic lacerations in the mucosa, thereby increasing the absorption of the nicotine and carcinogens. Chronic irritation to oral soft tissue may precede the formation of premalignant or malignant epithelial lesions in susceptible individuals. Perhaps more importantly, the microulceration and chronic inflammation facilitate the ingress of tobacco constituents and provide the carcinogens with increased cellular contact.13

In the United States, tobacco use, though declining, is still pervasive, resulting in significant morbidity and mortality to both users and nonusers.14 Worldwide, tobacco use continues to increase. Cigarette smoking is a major risk factor for heart disease, various forms of cancer (oral and systemic), stroke, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. It is estimated that one in five deaths is related to smoking and that one in four smokers will die prematurely of a tobacco-related disease, losing on average 15 years of life.8 Women who smoke are at risk for the same adverse effects as men and, in addition, a pregnant woman who smokes also puts her unborn child at risk for complications, such as premature birth and low birth weight. Tobacco smoking causes 30% of all cancer deaths in the United States.14 Tobacco smoking has been cited as the leading preventable cause of mortality and morbidity worldwide.15 The morbidity and mortality from cigarette smoking are related to the total years of smoking, the number of cigarettes per day, and the depth of inhalation. The use of nonfiltered cigarettes and mentholated cigarettes is also related to increased morbidity.16 Examples of tobacco products for smoking are seen in Figure 11-4.

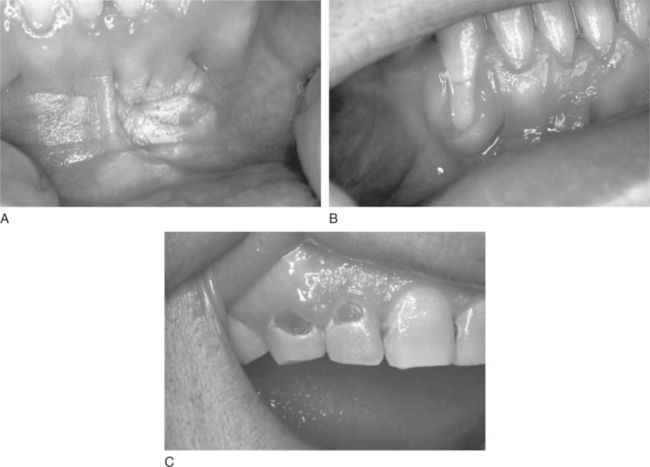

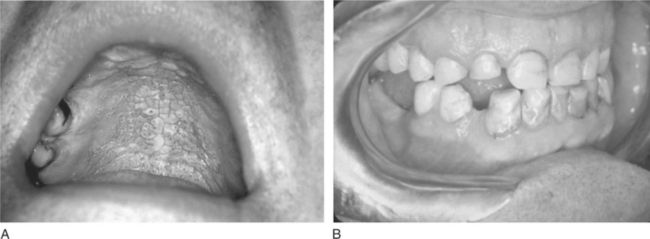

Cigar and pipe smoking are associated with the same health concerns as cigarette smoking, including systemic and upper aerodigestive tract diseases, the risk of nicotine addiction, and the creation of indoor air pollution.17 Cigar and pipe smoking are considered at least as great a risk factor for the development of oral cancer as cigarette smoking.4,17 The pipe stem (smoke delivery end) delivers smoke that has both thermal effects and hot gasses produced during combustion. These act synergistically with the toxic components in tobacco smoke to enhance the risk of carcinogenesis in chronically exposed tissues, such as lips and oral soft palate. The habit of holding the lighted end of the cigarette inside the mouth, called “reverse smoking,” is also associated with a significantly higher risk of oral cancer.2,4 Oral effects of pipe smoking are shown in Figure 11-5.

Figure 11-5 Pipe effects on oral tissue. A, Nicotine stomatitis. B, Attrition of both canines and the right maxillary lateral incisor from habitual pipe smoking in a 60-year-old male.

Currently, there are as many as 46 million smokers in the United States14 and an unknown yet important number of individuals who are indirectly exposed to passive or second-hand smoke. The second-hand smoke from cigarettes, cigars, and pipes is air pollution that poses health risks to nonsmokers.13The oral use of smokeless tobacco (commonly called spit, chew, or snuff) is not a safe alternative to smoking.6,13,18 Compelling scientific evidence documents the fact that smokeless tobacco is also dangerous, and can lead to nicotine addiction and a number of noncancerous oral pathologic conditions demonstrated in Figure 11-6. Types of smokeless tobacco to be chewed are shredded loose-leaf, pressed brick or plug, or twist made of dried ropelike strands. Snuff is a powdered or finely cut cured tobacco, which is available as a wet or dry product to be used topically in the mouth or nose. An example of smokeless tobacco is shown in Figure 11-7. All forms contain nitrosamines and other potentially carcinogenic substances. The risk of developing oral cancer increases with long-term use of smokeless tobacco.

Alcohol

Although not considered to be an oral carcinogen itself, some research suggests that alcohol consumption may add to the risk of oral cancer.1,2,4,6,19 Alcohol consumption potentiates the oral carcinogenic effect of tobacco. It has been hypothesized that alcohol’s drying effect may result in mucosa that is more susceptible to carcinogens. Ethanol may act as a solvent for tobacco carcinogens or a promoter for chemical carcinogenesis. Alcoholic beverages contain carcinogens, such as nitrosamines and polycyclic hydrocarbons.2 It is estimated that smoking tobacco and drinking alcohol combine to account for approximately three fourths of all oral and oropharyngeal cancers in the United States.2,5,20,21 (See also Chapter 12 for additional information on the adverse effects, pathophysiology, and addictive qualities of alcohol.)

Other Causes

In addition to tobacco and alcohol, a number of other factors may increase the risk of developing oral cancer. Chronic candidiasis has been suggested as a predisposing factor for oral squamous cell carcinoma.1,2,4 Studies have shown that the HPV is found in up to 50% of oral squamous cell carcinoma lesions.4,22 Patients with prolonged exposure to direct sunlight and lack of appropriate sun protection barriers are at greater risk for having cancers of the head and neck develop (basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, or malignant melanoma). A compromised immune system may also render patients at an increased risk for having cancer develop. Patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), bone marrow and kidney transplant recipients, and patients who have had total-body radiation and high-dose chemotherapy are also at a higher risk of having squamous cell carcinoma develop. Oral submucosal fibrosis and chronic forms of oral lichen planus may predispose the oral mucosa to having squamous cell carcinoma develop.1 In some cultures, chewing betel (areca) nut is common and appears to be related to the increased incidence of oral cancer.1,6 Although chronic irritation is not generally believed to initiate oral cancer, it is not uncommon to find a cancer at a site of irritation. It is therefore important to have the patient return so that any oral lesions can be reevaluated, even those apparently related to a dental prosthesis.1,4

Current cancer research evaluates ways in which inherited genes may influence the risks, classification, prognosis, and treatment of head and head cancer. Microassay methodology now allows the expression of thousands of genes to be studied simultaneously. The researcher can provide gene expression profiling (GEP) for a single patient’s cancer. Comparisons of gene expression patterns between patients with the same type of cancer may allow differentiation of tumors with a poor prognosis from others with better prospective outcomes. The future is expected to open new avenues for cancer prevention and treatment.2,4,23,24

ROLE OF THE DENTAL TEAM IN HEAD AND NECK CANCER

Patient Education

The dental team plays a crucial role in educating patients about oral cancers and the associated risk factors (see the Dental Team Focus box).5,7,21,25 Because many individuals may be more likely to visit the dentist than the physician for periodic or episodic visits, the dental team has a special responsibility to identify potentially malignant oral lesions and provide critical oral health information to the patient. Patients need to know if they are at risk and what they can do for the prevention of oral cancer. Excellent pamphlets are available to use as teaching tools and may be kept in the waiting area of a dental office. Specific prevention and tobacco cessation strategies are discussed later in this chapter.

Patient History

Interviewing patients to identify risk factors for oral cancer is an important part of taking the dental and medical history.5,21,25 Although gender, race, and age are easy data to gather, many people underreport their use of alcohol and tobacco. Because patients with a history of smoking or drinking are at greater risk for oral cancer, special attention should be given to obtaining accurate information on these habits. “Do you smoke?” is a simple question that may elicit an answer of “No,” but asking the same patient, “Have you ever smoked or used any type of tobacco?” may reveal a more accurate history. Further questions are needed to determine the extent of usage, including amount, length of time, and type of tobacco used since a patient may have smoked more in the past or may have recently quit smoking. These factors can be incorporated into a “pack-year” smoking history, used by some providers. Some sample questions concerning smoking history and oral changes are found in Box 11-1.

Findings from the Clinical Examination: Signs and Symptoms

The head and neck cancer examination must be part of every complete examination and should be repeated at each maintenance visit, whether the patient is seen by the dentist or the dental hygienist. (See Chapter 1 for more information.) The dental team should inform the patient that the purpose of this examination is to identify any change that may be a sign of oral cancer.5 The clinician may explain the process during the examination, discussing examples of signs or symptoms that may or may not raise a concern. This is also a good opportunity to involve the patient in his or her own oral self-assessment and encourage the individual to carefully monitor lesions that are deemed benign but that need periodic follow-up. This may also provide an excellent opportunity to educate the patient about the risks of oral cancer and any recommended prevention strategies, particularly if the patient is using tobacco.

The oral cancer screening examination includes a thorough systematic visual inspection and palpation of extraoral and intraoral structures. This can be accomplished effectively in minutes and requires only adequate lighting, a dental mouth mirror, and a gauze square. If the same sequence is followed each time an exam is performed, it is unlikely that even a small lesion will be overlooked. See Box 11-2 for steps of an oral cancer screening examination. The practitioner should document any lesion’s appearance on a drawing as in Figure 11-8, or with a photograph or digital image. The size of the lesion may be measured using a small ruler or even a periodontal probe. Examples of suitable dental instruments used to measure oral lesions are seen in Figure 11-9.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses