Moderate Nonskeletal Problems in Preadolescent Children

Preventive and Interceptive Treatment in Family Practice

Orthodontic Triage: Distinguishing Moderate from Complex Treatment Problems

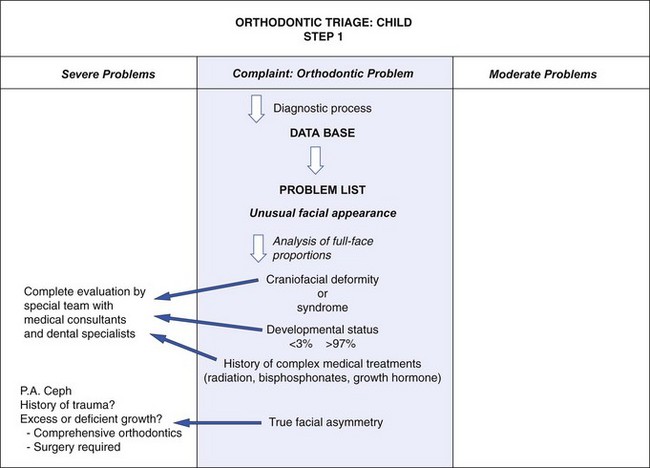

This section presents a logical scheme for orthodontic triage for children. It is based on the diagnostic approach developed in Chapter 6 and incorporates the principles of determining treatment need that have been discussed. An adequate database and a thorough problem list, of course, are necessary to carry out the triage process. A cephalometric radiograph is not required since a facial form analysis is more appropriate in the generalist’s office, but appropriate dental radiographs are needed (usually, a panoramic film; occasionally, bitewings supplemented with anterior occlusal radiographs) as are dental casts and photographs. A space analysis (see later in this chapter) is essential. A flow chart illustrating the steps in the triage sequence accompanies this section.

Step 1: Syndromes and Developmental Abnormalities

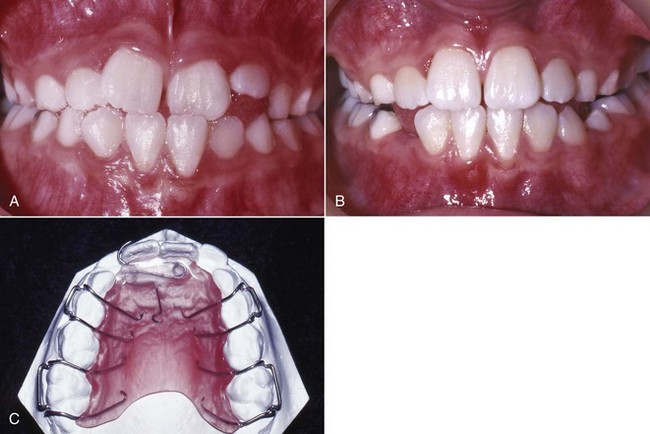

The first step in the triage process is to separate out patients with facial syndromes and similarly complex problems (Figure 11-1) so they can be treated by specialists or teams of specialists. From physical appearance, the medical and dental histories, and an evaluation of developmental status, nearly all such patients are easily recognized. Examples of these disorders are cleft lip or palate, Treacher Collins syndrome, hemifacial microsomia, and Crouzon’s syndrome (see Chapter 3). Complex medical treatments, such as radiation, bisphosphonates, and growth hormones, can affect dentofacial development and responses to treatment. Patients who appear to be developing either above the 97th or below the third percentiles on standard growth charts require special evaluation. Growth disorders may demand that any orthodontic treatment be carried out in conjunction with endocrine, nutritional, or psychologic therapy. For these patients and those with diseases that affect growth, such as juvenile rheumatoid arthritis, the proper orthodontic therapy must be combined with identification and control of the disease process.

FIGURE 11-1 Orthodontic triage, step 1.

Patients with significant skeletal asymmetry (not necessarily those whose asymmetry results from only a functional shift of the mandible due to dental interferences caused by crossbites) always fall into the severe problem category (Figure 11-2). These patients could have a developmental problem or the growth anomaly could be the result of an injury. Treatment is likely to involve growth modification and/or surgery, in addition to comprehensive orthodontics. Timing of intervention is affected by whether the cause of the asymmetry is deficient or excessive growth (see Chapter 13), but early comprehensive evaluation is always indicated.

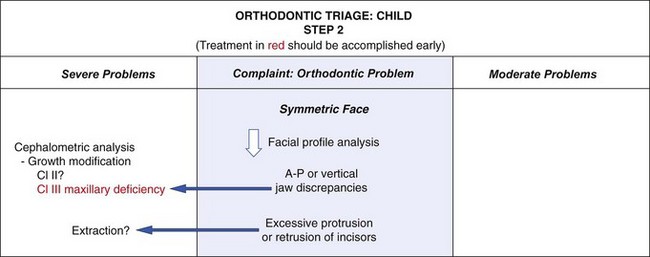

Step 2: Facial Profile Analysis (Figure 11-3)

Anteroposterior and Vertical Problems

Skeletal Class II and Class III problems and vertical deformities of the long-face and short-face types, regardless of their cause, require thorough cephalometric evaluation to plan appropriate treatment and its timing and must be considered complex problems (Figure 11-4). Issues in treatment planning for growth modification are discussed in Chapter 13. As a general rule, Class II treatment can be deferred until near adolescence and be equally effective as earlier treatment, while Class III treatment for maxillary deficiencies should be addressed earlier. Class III treatment for protrusive mandibles appears equally ineffective whenever it is attempted. Treatment of both long- and short-face problems probably can be deferred, since the former is due to growth that persists until the late teens and outstrips early focused intervention, and the latter usually can be managed well with comprehensive treatment during adolescence. As with asymmetry, early evaluation is indicated even if treatment is deferred, so early referral is appropriate.

FIGURE 11-3 Orthodontic triage, step 2.

Excessive Dental Protrusion or Retrusion

Some individuals with good skeletal proportions have protrusion of incisor teeth rather than crowding (Figure 11-5). When this occurs, the space analysis will show a small or nonexistent discrepancy because the incisor protrusion has compensated for the potential crowding. Excessive protrusion of incisors (bimaxillary protrusion, not excessive overjet) usually is an indication for premolar extraction and retraction of the protruding incisors. This is complex and prolonged treatment. Because of the profile changes produced by adolescent growth, it is better for most children to defer extraction to correct protrusion until late in the mixed dentition or early in the permanent dentition. Techniques for controlling the amount of incisor retraction are described in Chapter 15.

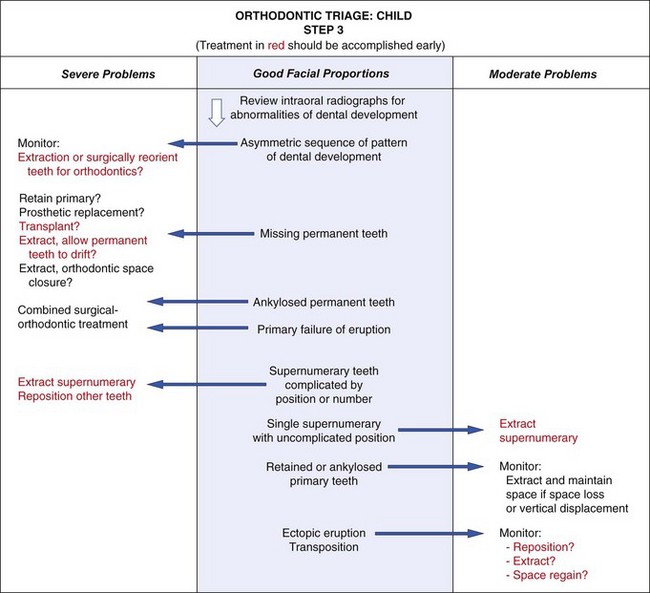

Step 3: Dental Development

Unlike the more complex skeletal problems and problems related to protruding incisors, problems involving dental development often need treatment as soon as they are discovered, typically during the early mixed dentition, and often can be handled in family practice. Considerations in making that decision are outlined in Figure 11-6, and treatment of the less severe problems of this type is presented in detail in this chapter.

FIGURE 11-6 Orthodontic triage, step 3.

Missing Permanent Teeth

The treatment possibilities differ slightly for anterior and posterior teeth. For missing posterior teeth, it is possible to (1) maintain the primary tooth or teeth, (2) extract the overlying primary teeth and then allow the adjacent permanent teeth to drift, (3) extract the primary teeth followed by immediate orthodontic treatment, or (4) replace the missing teeth prosthetically or perhaps by transplantation or an implant later. For anterior teeth, maintaining the primary teeth is often less of an option due to the esthetics and the spontaneous eruption of adjacent permanent teeth into the space of the missing tooth. Also, extraction and drift of the adjacent teeth is less appealing because anterior edentulous ridges deteriorate quickly. As with other growth problems, early evaluation and planning is essential. Treatment of missing tooth problems in mixed dentition children is discussed in more detail in Chapter 12.

Other Eruption Problems

Ectopic eruption (eruption of a tooth in the wrong place, or along the wrong eruption path) often leads to early loss of a primary tooth, but in severe cases, resorption of permanent teeth can result. Repositioning of the ectopically erupting tooth may be indicated, either surgically or by exposing the problem tooth, placing an attachment on it, and applying traction. A dramatic variation of ectopic eruption is transposition of teeth. Early intervention can reduce the extent to which teeth are malpositioned in some cases. These severe problems often require a combination of surgery and orthodontics and may be genetically linked to other anomalies. They are discussed in Chapter 12.

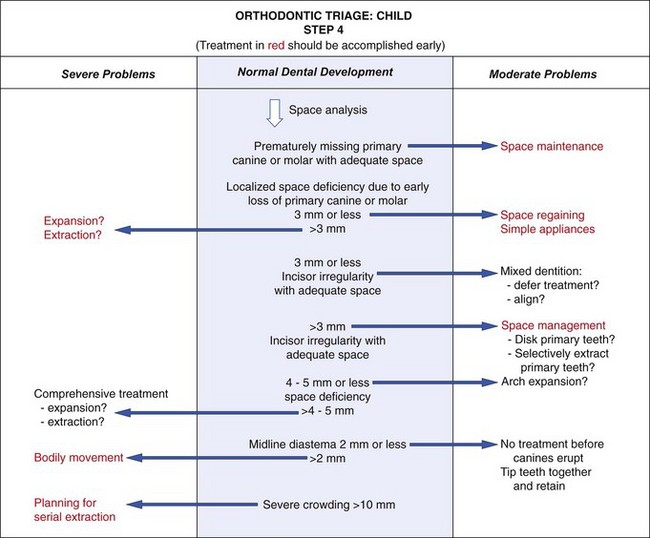

Step 4: Space Problems

Orthodontic problems in a child with good facial proportions involve crowding, irregularity, or malposition of the teeth (Figure 11-7). At this stage, regardless of whether crowding is apparent, the results of space analysis are essential for planning treatment. The presence or absence of adequate space for the teeth must be taken into account when other treatment is planned.

FIGURE 11-7 Orthodontic triage, Step 4.

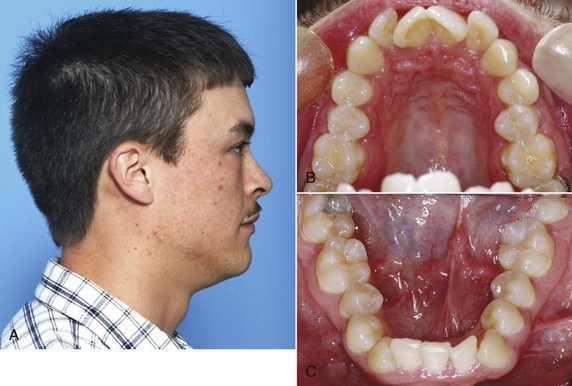

In interpreting the results of space analysis for patients of any age, remember that if space to align the teeth is inadequate, either of two conditions may develop. One possibility is for the incisor teeth to remain upright and well positioned over the basal bone of the maxilla or mandible and then rotate or tip labially or lingually. In this instance, the potential crowding is expressed as actual crowding and is difficult to miss (Figure 11-8). The other possibility is for the crowded teeth to align themselves completely or partially at the expense of the lips, displacing the lips forward and separating them at rest (see Figure 11-5). Even if the potential for crowding is extreme, the teeth can align themselves at the expense of the lip, interfering with lip closure. This must be detected on profile examination. If there is already a degree of protrusion in addition to the crowding, it is safe to presume that the natural limits of anterior displacement of incisors have been reached.

FIGURE 11-8 In some patients, as in this young adult (A), potential crowding is expressed completely as actual crowding (B and C) with no compensation in the form of dental and lip protrusion. In others (see Figure 11-5) potential crowding is expressed as protrusion. The teeth end up in a position of equilibrium between the tongue and lip forces against them (see Chapter 5).

Step 5: Other Occlusal Discrepancies

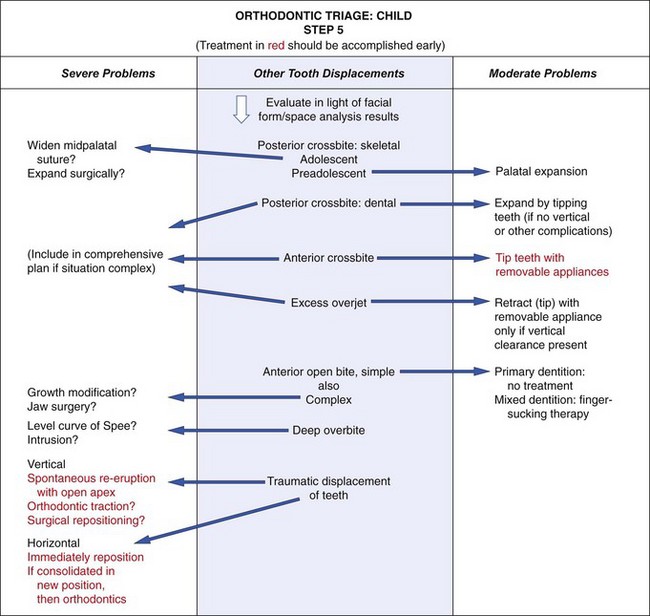

Whether crossbite and overbite/open bite should be classified as moderate or severe is determined for most children from their facial form (Figure 11-9). Mixed dentition treatment for all of these problems must be discussed in the context of “should be treated” versus “can be treated.”

FIGURE 11-9 Orthodontic triage, step 5.

Anterior open bite in a young child with good facial proportions usually needs no treatment because there is a good chance of spontaneous correction with additional incisor eruption, especially if the open bite is related to an oral habit like finger sucking. A complex open bite (one with skeletal involvement or posterior manifestations) or any open bite in an older patient is a severe problem. A deep overbite can develop in several ways (see Chapter 6) but often is caused by or made worse by short anterior face height. This is seldom treated in the mixed dentition.

Traumatically displaced erupted incisors pose a special problem because of the resulting occlusal problems. There is a risk of ankylosis after healing occurs, especially after traumatic intrusion. If the apex is open and root development is incomplete, waiting for spontaneous re-eruption is warranted. If the injuries are more severe or in older patients, either immediate orthodontic or surgical treatment is needed, and the long-term prognosis must be guarded. Treatment planning after trauma is discussed in Chapter 13.

This triage scheme is oriented toward helping the family practitioner decide which children with orthodontic problems to treat and which to refer. Treatment for children with moderate nonskeletal problems, those selected for treatment in family practice using the triage scheme, is discussed later in this chapter. Early (preadolescent) treatment of more severe and complex nonskeletal problems is discussed in Chapter 12, and treatment for skeletal problems is discussed in Chapter 13.

Management of Occlusal Relationship Problems

Posterior crossbite in mixed dentition children is reasonably common, occurring in 7.1% of U.S. children aged 8 to 11.1 It usually results from a narrowing of the maxillary arch and often is present in children who have had prolonged sucking habits. The crossbite can be due to a narrow maxilla (i.e., to skeletal dimensions) or due only to lingual tipping of the maxillary teeth. If the child shifts on closure or if the constriction is severe enough to significantly reduce the space within the arch, early correction is indicated. If not, treatment can be deferred, especially if other problems suggest that comprehensive orthodontics will be needed later.

Correcting posterior crossbites in the mixed dentition increases arch circumference and provides more room for the permanent teeth. On the average, a 1 mm increase in the inter-premolar width increases arch perimeter values by 0.7 mm.2 Total relapse into crossbite is unlikely in the absence of a skeletal problem, and mixed dentition expansion reduces the incidence of posterior crossbite in the permanent dentition, so early correction also simplifies future diagnosis and treatment by eliminating at least that problem from the list.

Although it is important to determine whether the crossbite is skeletal or dental, in the early mixed dentition years the treatment is usually the same, since relatively light forces will move teeth and bones. An expansion lingual arch is the best choice at this age—heavy force from a jackscrew device is needed only when the midpalatal suture has become significantly interdigitated during adolescence (Figure 11-10; also see Chapter 13). Heavy force and rapid expansion are not indicated in the primary or early mixed dentition. There is a significant risk of distortion of the nose if this is done in younger children (see Figure 7-8).

There are three basic approaches to the treatment of moderate posterior crossbites in children:

1. Equilibration to Eliminate Mandibular Shift

In a few cases, mostly observed in the primary or early mixed dentition, a shift into posterior crossbite will be due solely to occlusal interference caused by the primary canines or (less frequently) primary molars. These patients can be diagnosed by carefully positioning the mandible in centric occlusion; then it can be seen that the width of the maxilla is adequate and that there would be no crossbite without the shift (Figure 11-11). In this case, a child requires only limited equilibration of the primary teeth (often, just reduction of the primary canines) to eliminate the interference and the resulting lateral shift into crossbite.3

2. Expansion of a Constricted Maxillary Arch

More commonly, a lateral shift into crossbite is caused by constriction of the maxillary arch. Even a small constriction creates dental interferences that force the mandible to shift to a new position for maximum intercuspation (Figure 11-12), and moderate expansion of the maxillary dental arch is needed for correction. The general guideline is to expand to prevent the shift when it is diagnosed, but there is an exception: if the permanent first molars are expected to erupt in less than 6 months, it is better to wait for their eruption so that correction can include these teeth, if necessary. A greater maxillary constriction may allow the maxillary teeth to fit inside the mandibular teeth—if so, there will not be a shift on closure (Figure 11-13), and there is less reason to provide early correction of the crossbite.

Although it is possible to treat posterior crossbite with a split-plate type of removable appliance, there are three problems: this relies on patient compliance for success, treatment time is longer, and it is more costly than an expansion lingual arch.4 The preferred appliance for a preadolescent child is an adjustable lingual arch that requires little patient cooperation.

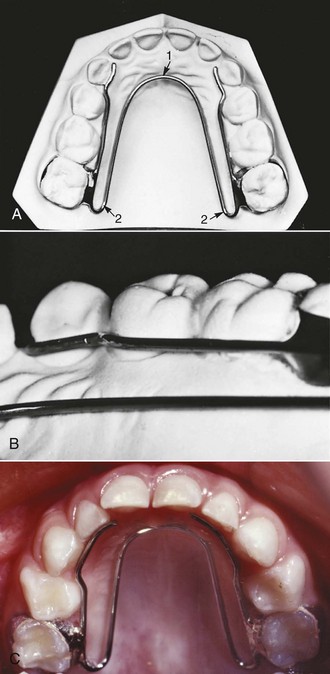

Both the W-arch and the quad helix are reliable and easy to use. The W-arch is a fixed appliance constructed of 36 mil steel wire soldered to molar bands (Figure 11-14). It is activated simply by opening the apices of the W and is easily adjusted to provide more anterior than posterior expansion, or vice versa, if this is desired. The appliance delivers proper force levels when opened 4 to 6 mm wider than the passive width and should be adjusted to this dimension before being cemented. It is not uncommon for the teeth and maxilla to move more on one side than the other, so precise bilateral expansion is the exception rather than the rule, but acceptable correction and tooth position are almost always achieved.

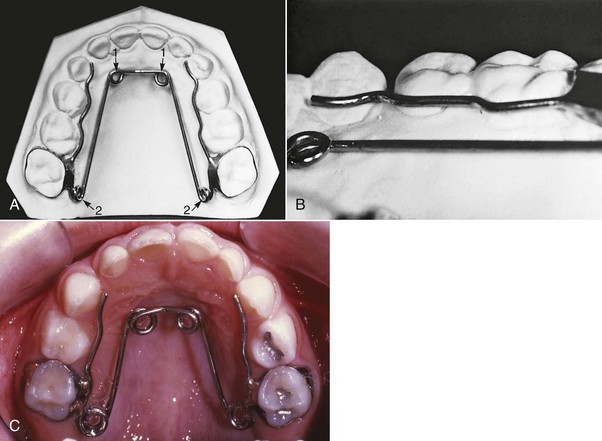

The quad helix (Figure 11-15) is a more flexible version of the W-arch, although it is made with 38 mil steel wire. The helices in the anterior palate are bulky, which can effectively serve as a reminder to aid in stopping a finger habit. The combination of a posterior crossbite and a finger-sucking habit is the best indication for this appliance. The extra wire incorporated in it gives it a slightly greater range of action than the W-arch, but the forces are equivalent. Soft tissue irritation can become a problem with the quad helix. Both the W-arch and the quad helix leave an imprint on the tongue. Both the parents and child should be warned about this (Figure 11-16). The imprint will disappear when the appliance is removed but can take up to a year to totally do so.

With both types of expansion lingual arches, some opening of the midpalatal suture can be expected in a primary or mixed dentition child, so the expansion is not solely dental. Expansion should continue at the rate of 2 mm per month (1 mm on each side) until the crossbite is slightly overcorrected. In other words, the lingual cusps of the maxillary teeth should occlude on the lingual inclines of the buccal cusps of the mandibular molars at the end of active treatment (Figure 11-17). Intraoral appliance adjustment is possible but may lead to unexpected changes. For this reason, removal and re-cementation are recommended at each active treatment visit. Most posterior crossbites require 2 to 3 months of active treatment (with the patients seen each month for adjustments) and 3 months of retention (during which the lingual arch is left passively in place). This mixed dentition correction appears to be stable in the long term.5

3. Unilateral Repositioning of Teeth

Some children do have a true unilateral crossbite due to unilateral maxillary constriction of the upper arch (Figure 11-18). In these cases, the ideal treatment is to move selected teeth on the constricted side. To a limited extent, this goal of asymmetric movement can be achieved by using different length arms on a W-arch or quad helix (Figure 11-19), but some bilateral expansion must be expected. An alternative is to use a mandibular lingual arch to stabilize the lower teeth and attach cross-elastics to the maxillary teeth that are at fault. This is more complicated and requires cooperation to be successful but is more unilateral in its effect.

All of the appliances described above are aimed at correction of teeth in the maxillary arch, which is usually where the problem is located. If teeth in both arches contribute to the problem, cross-elastics between banded or bonded attachments in both arches (Figure 11-20) can reposition both upper and lower teeth. The best choice is a latex elastic with a  -inch (5 mm) lumen generating 6 ounces (170 gm) of force. The force from the elastics is directed vertically as well as faciolingually, which will extrude the posterior teeth and reduce the overbite. Therefore cross-elastics should be used with caution in children with increased lower face height or limited overbite. Crossbites treated with elastics should be overcorrected, and the bands or bonds left in place immediately after active treatment. If there is too much relapse, the elastics can be reinstated without rebanding or rebonding. When the occlusion is stable after several weeks without elastic force, the attachments can be removed. The most common problem with this form of crossbite correction is lack of cooperation from the child.

-inch (5 mm) lumen generating 6 ounces (170 gm) of force. The force from the elastics is directed vertically as well as faciolingually, which will extrude the posterior teeth and reduce the overbite. Therefore cross-elastics should be used with caution in children with increased lower face height or limited overbite. Crossbites treated with elastics should be overcorrected, and the bands or bonds left in place immediately after active treatment. If there is too much relapse, the elastics can be reinstated without rebanding or rebonding. When the occlusion is stable after several weeks without elastic force, the attachments can be removed. The most common problem with this form of crossbite correction is lack of cooperation from the child.

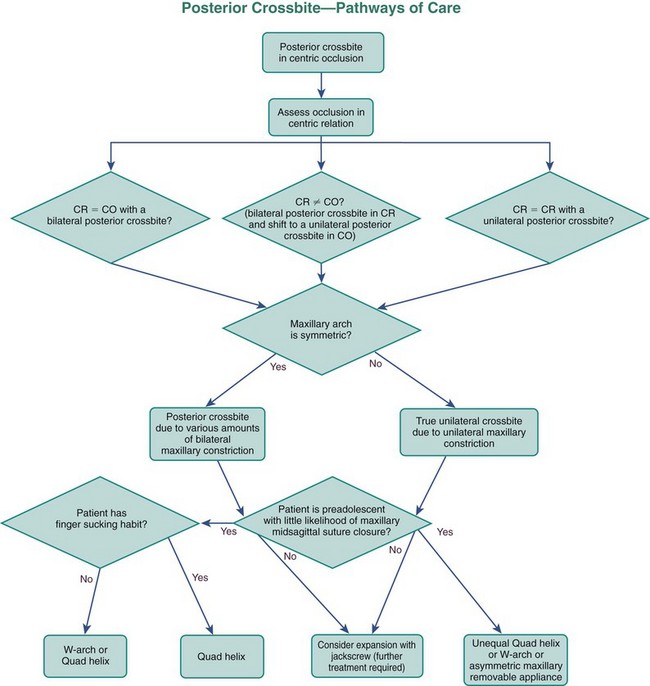

A flowchart is provided to help guide decision making for posterior crossbites (Figure 11-21).

FIGURE 11-21 This flowchart can be used to aid decision making regarding possible options for posterior crossbite correction in the primary and mixed dentitions. Answers to the questions posed in the chart should lead to successful treatment pathways. The approaches to skeletal correction of posterior crossbites are described in Chapter 13.

Anterior Crossbite

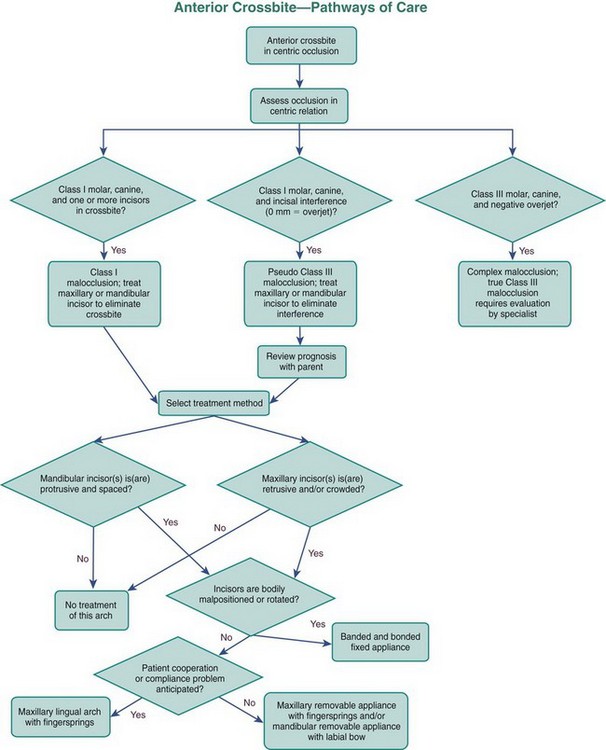

Anterior crossbite, particularly crossbite of all of the incisors, is rarely found in children who do not have a skeletal Class III jaw relationship. A crossbite relationship of one or two anterior teeth, however, may develop in a child who has good facial proportions. When racial/ethnic groups in the U.S. population are combined, about 3% of children have an anterior crossbite in the mixed dentition (see Figure 1-7).

In planning treatment for anterior crossbites, it is critically important to differentiate skeletal problems of deficient maxillary or excessive mandibular growth from crossbites due only to displacement of teeth.6 If the problem is truly skeletal, simply changing the incisor position is inadequate treatment, especially in more severe cases (see Chapter 13).

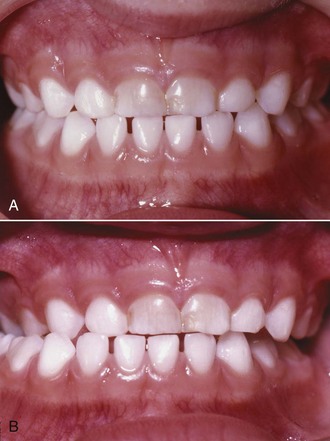

Anterior crossbite affecting only one or two teeth almost always is due to lingually displaced maxillary central or lateral incisors. These teeth tend to erupt to the lingual because of the lingual position of the developing tooth buds and may be trapped in that location, especially if there is not enough space (Figure 11-22). Sometimes, central incisors are involved because they were deflected toward a lingual eruption path by supernumerary anterior teeth or overretained primary incisors. More rarely, trauma to maxillary primary teeth reorients a permanent tooth bud or buds lingually.

The most common etiologic factor for nonskeletal anterior crossbites is lack of space for the permanent incisors, and it is important to focus the treatment plan on management of the total space situation, not just the crossbite. If the developing crossbite is discovered before eruption is complete and overbite has not been established, the adjacent primary teeth can be extracted to provide the necessary space (Figure 11-23).

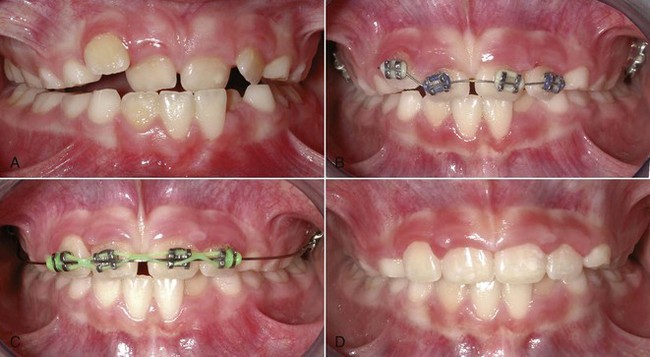

Treatment of Nonskeletal Anterior Crossbite

In a young child, one way to tip the maxillary and mandibular anterior teeth out of crossbite is with a removable appliance, using fingersprings for facial movement of maxillary incisors (Figure 11-24) or, less frequently, an active labial bow for lingual movement of mandibular incisors. Two maxillary anterior teeth can be moved facially with one 22-mil double-helical cantilever spring. The appliance should have multiple clasps for retention, but a labial bow is usually contraindicated because it can interfere with facial movement of the incisors and would add little or no retention.

One of the simplest fixed appliances for correction of maxillary incisors with a moderate anterior crossbite is a maxillary lingual arch with fingersprings (sometimes referred to as whip springs). This appliance (Figure 11-25) is indicated for a child with whom compliance problems are anticipated. The springs usually are soldered on the opposite side of the arch from the tooth to be corrected, in order to increase their length. They are most effective if they are approximately 15 mm long. When these springs are activated properly at each monthly visit (advancing the spring about 3 mm), they produce tooth movement at the optimum rate of 1 mm per month. The greatest problems are distortion and breakage from poor patient cooperation and poor oral hygiene, which can lead to decalcification and decay.

It also is possible to tip the maxillary incisors forward with a 2 × 4 fixed appliance (2 molar bands, 4 bonded incisor brackets). In the rare instance when there is no skeletal component to the anterior crossbite, this is the best choice for a mixed dentition patient with crowding, rotations, the need for bodily movement, and more permanent teeth in crossbite (Figure 11-26). When the anterior teeth are bonded and moved prior to permanent canine eruption, it is best to place the lateral incisor brackets with some increased mesial root tip so that the roots of the lateral incisors are not repositioned into the canine path of eruption, with resultant resorption of the lateral incisor roots. If torque or bodily repositioning is needed for these teeth, finishing with a rectangular wire is required even in early mixed dentition treatment. Otherwise, the teeth will tip back into crossbite again.

See Figure 11-27 for a flowchart to help guide decision making for anterior crossbites.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses