Chapter 11

Maxillary antrum

Introduction

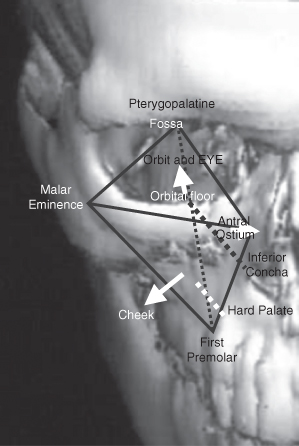

The maxillary antrum (also known as the “maxillary sinus”) occupies a considerable part of the midface and is surrounded by important structures and organs. These are the orbits, the nasal and oral cavities, the ethmoid sinuses, the pterygopalatine and infratemporal fossae. Therefore, disease arising within it can involve these structures in addition to disease arising within them involving it in turn. The shape of the maxillary antrum forms an inverted pyramid with its apex set laterally at the root of the temporal process of the zygoma (Figure 11.1). Its central position within hemi-midface means that it is involved in most maxillary fractures as the three struts joining the maxilla with the skull base. These struts arising from two of the four angles of the antral cavity are the frontozygomatic the zygomaticotemporal and the frontomaxillary. They transmit the occlusal forces from the dentoalveolar process to the skull base.

Figure 11.1. The anatomical parameters of the maxillary antrum.

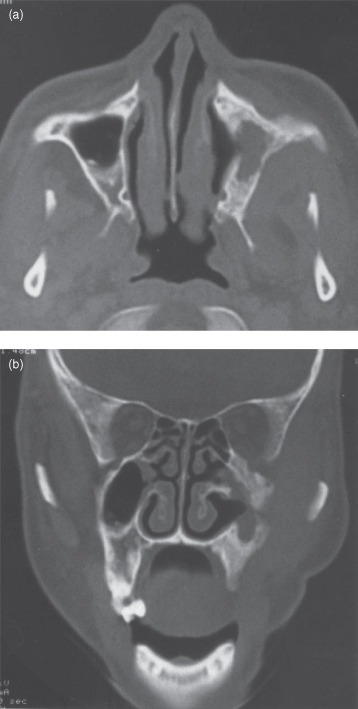

The maxillary antrum has a communication with the nasal cavity via an ostium over half way up the medial wall above the attachment of the inferior turbinate (concha) (Figure 11.2). This is the sole or at least the main point of egress for the antral fluids. An accessory osteum may be present. Normal evacuation is dependent upon the integrity of the pseudostriated squamous epithelium that lines the lumen of the antrum.

Figure 11.2. Normal maxillary antrum (MA) coronal helical computed tomography displaying the midface at the level of the osteum of the MA. The ostium’s position, above the inferior concha is toward the roof of the MA. The inferior orbital canal is laterally positioned anteriorly to the lumen of the hypoplastic MA. Note: The white rim represents the mucosal surface enhancing postcontrast. The darker part is the soft-tissue of the turbinates.

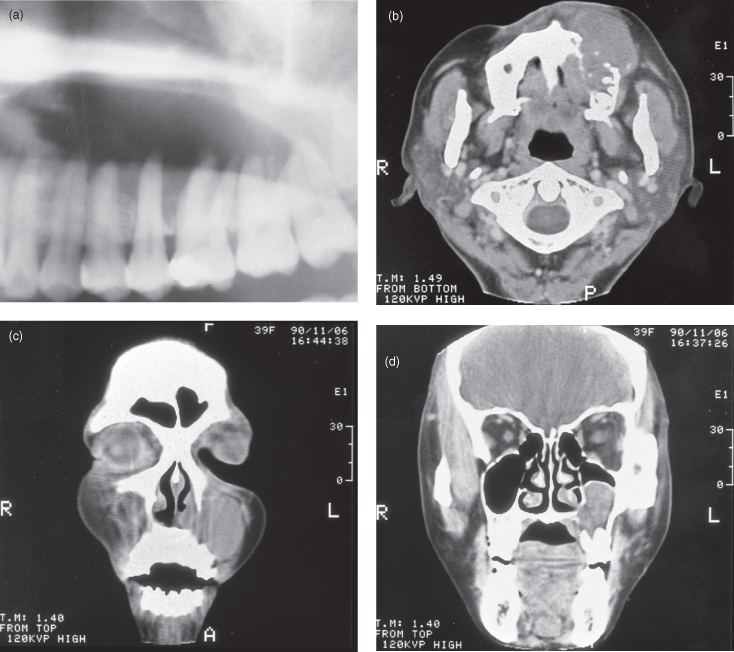

The hard palate established the junction between the alveolar and basal process of the upper jaw, as did the mandibular canal for the mandible.1 The profile of the hard palate is readily observed on lateral projections of the jaws, including panoramic radiographs (see Figure 1.24). The maxillary antrum frequently pneumatizes this process, particularly in the premolar region. Therefore diseases arising within this process or treatment for these diseases may involve the maxillary antrum. Extensive pneumatization of the alveolar process, as seen in Figure 11.3a), may indicate the presence of a lesion.

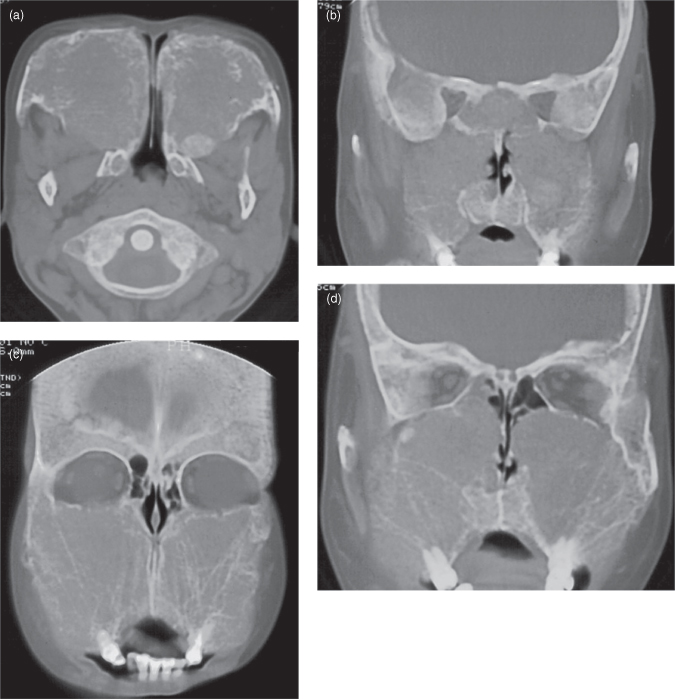

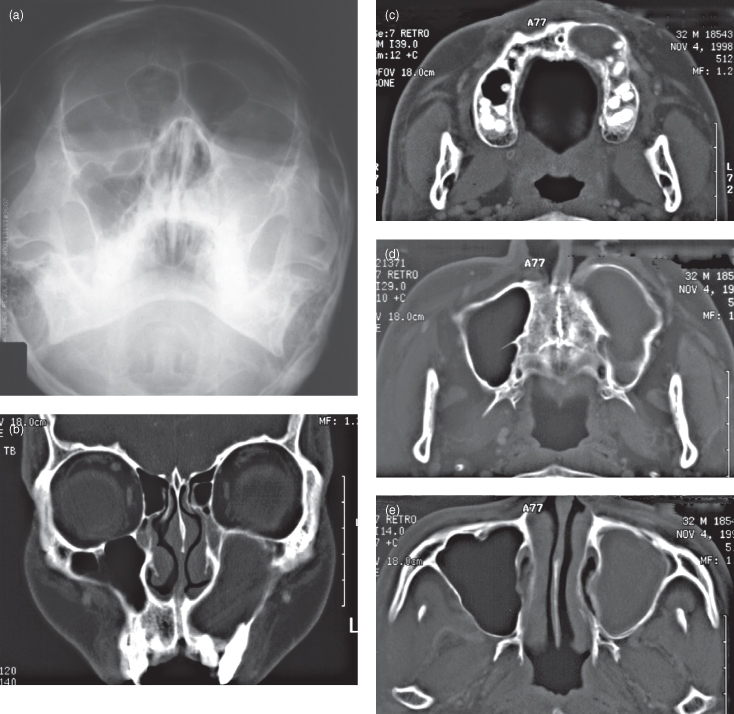

Figure 11.3. The panoramic radiograph and three soft-tissue window computed tomographs (CT) of a case of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL) that arose from lymphoid tissue within the alveolus. Although the majority of NHLs arise within Waldeyer’s ring, a number can arise outside it. They are generally bone sparing, unless they arise in bone itself. The breaching of the buccal and palatal cortices and substantial soft-tissue mass are reminiscent of a squamous cell carcinoma, but both the substantial palatal expansion and concave upward expansion of the floor of the maxillary antrum are more typical of a benign neoplasm or cyst. (a) The panoramic radiograph displays extensive loss of bone around the roots of maxillary molars in addition to premolars. This degree of bone loss far exceeds normal pneumatization of the alveolus. (b) Axial CT, at the level of the first cervical vertebra. The alveolar bone around the roots on the left side appear to have been resorbed. The buccal cortex is absent, whereas the palatal cortex is expanded, but it eroded with some perforations. The buccal soft-tissue mass has extended medially between the surface of the anterior alveolus and the skin of the upper lip. (c) Coronal CT, at the level of the first premolars, almost occludes the left antral and nasal cavities, leaving a residual air space just below the medial portion of the orbital floor. The medial and lateral bony walls, in addition to a considerable portion of the alveolar process are absent. The soft-tissue mass of the lesions has expanded medially into the nasal cavity. (d) Coronal CT, at the level of the first molars, has perforated the palatal cortex and expanded into the palatal submucosa, whereas the lateral wall appears intact. The lesion is separated from the floor of the orbit by a residual air space. The dome-shaped surface of the lesion is delineated by a well-defined uniformly thick cortex.

Reprinted with permission from Li TK, MacDonald-Jankowski DS. An unusual presentation of a high-grade non Hodgkin’s lymphoma in the maxilla. Dentomaxillofacial Radiology 1991;20:224–226.

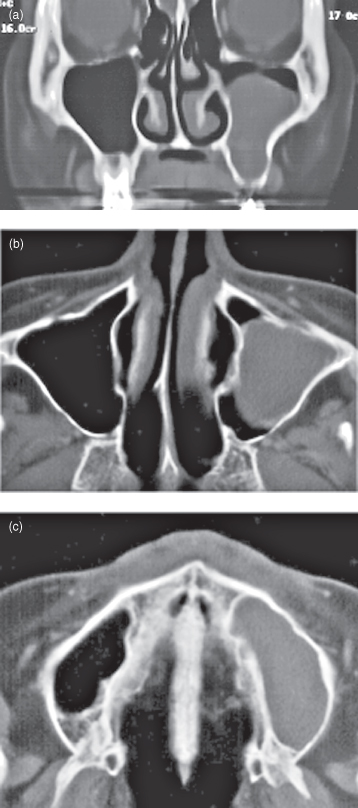

The maxillary antrum reaches adult size about 12 years of age. Chronic sinusitis during childhood has been suggested to be the cause of its failure to develop (aplasia) or its small size (hypoplasia) (Figures 11.4 and 11.5).2,3 Pneumatization is reduced by red-marrow conversion during anemia.2 Figure 11.6 exhibits a case of thalassemia, introduced in Chapter 9, affecting the maxillary antrum.

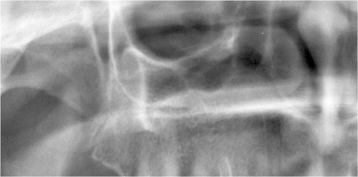

Figure 11.4. Panoramic radiograph displaying a very hypoplastic maxillary antrum.

Figure 11.5. Computed tomography (CT; bone windows) displaying a hemimaxilla which has been affected by osteomyelitis. This had resulted in loss of teeth and marked hypoplasia of the maxilla and also of the maxillary antrum. Some of the features of this lesion were secondary to the surgery required to remove sequestra and teeth. (a) Axial CT displays the hypoplasia of the residual maxilla and of the maxillary antrum. The latter cavity has been obturated with soft tissue. (b) Coronal CT displays the above. The floor of the orbit on the affected side is thicker. The inferior concha is not attached to the affected maxilla in this section. Note: Osteomyelitis affecting the maxilla usually affects children and is spread to the maxilla by the blood (hematogenous).

Figure 11.6. Computed tomography (bone windows) of thalassemia. See also Figures 9.5 and 17.21 for other images from the same patient. (a) Axial section, through the atlantoaxial articulation, reveals the complete absence of a maxillary antrum. The entire normal bone has been replaced by thickened and coarse trabeculae. There is a well-defined ovoid sclerosis on the posterior wall of the right maxilla. The cortex is either diffusely thickened or absent. Both maxillae are expanded. (b) Coronal section confirms the complete absence of the maxillary antrum observed in (b). The pattern of the background radiodensity is peau d’orange. (c) Coronal section through the middle of the globe (eyeball) displays the above. There are fewer trabeculae save for a few vertical trabeculae. The floor of the orbit is diffusely thickened or absent, whereas the roof is distinct and intact. (d) Coronal section, just behind the globe (note the rectus muscles and optic nerve). It displays the same pattern as (c). There is a small well-defined ovoid sclerosis just below the orbit on the right maxilla.

Although mucosal thickening of the maxillary antrum is common in symptom-free patients, it is considered normal if it is less than 4 mm (Figure 11.7).2

Figure 11.7. This axial computed tomograph (bone window) displays the normal triangular shape of the maxillary antrum (MA). Its degree of pneumatization, size, and shape are generally symmetrical. Note that the posteriolateral wall is sigmoid shaped. Neoplastic lesions generally expand the posterior half of this wall. Lumen of the MA on one side is nearly obturated by substantial expansion of the antral mucosa, leaving only a residual air space in the center. The other side reveals the presence of a shallow dome-shaped opacity of soft-tissue radiodensity arising from the anterior wall of the MA.

Sinusitis can be acute or chronic. A de novo acute sinusitis or an acute exacerbation of existing chronic sinusitis is generally painful. There may be a history of a recent upper respiratory tract infection. The intensity of the pain may vary with changes in position of the patient’s head. If the maxillary antrum is infected, there may be tenderness of the anterior maxilla, and the vital premolar and molar teeth may be tender to percussion or biting. The initial diagnosis can be concluded on clinical evidence alone. Although conventional radiography is often unhelpful, radiographs should be taken in cases of a long-standing history of sinusitis. Unlike the de novo acute sinusitis, long-standing chronic sinusitis may present with thickening of the sinus’s bony walls.2 If sinusitis remains unresponsive to antibiotics and decongestants, it is necessary to exclude the possibility of other underlying pathology, the most important being a squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) (see Figure 18.20). This can achieve considerable dimensions prior to manifestation of symptoms, of which chronic sinusitis is one. The earlier the diagnosis, the better the prognosis.

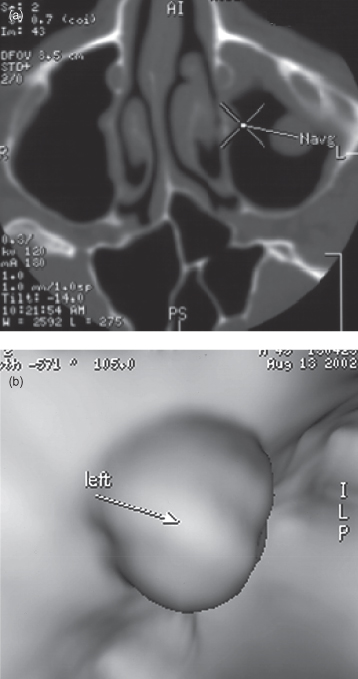

Osteosarcoma affecting the maxillary antrum displays the similar features reported earlier (Chapter 10). Figure 11.8 displays substantial soft-tissue involvement and swelling, which is not reflected by the extent of the radiologically apparent osseous (radiopaque) element of the disease.

Figure 11.8. Computed tomography (CT) of osteosarcoma affecting the anterior sextant of the maxilla and extending into the maxillary antrum (MA). (a) Sagital CT (bone window) exhibiting a poorly defined radiopacity displacing the roots of the canine and lateral incisor. Striae are present at the periphery of the lesion. The intraluminal mass is largely soft tissue with deeper sunburst striae. (b) Axial CT (bone window) displays a loss of the trabeculae and cortex at the anteriomedial angle of the MA and an invasion by a soft-tissue mass and striae deeper within it. The lateral surface of the medial wall of the MA presents with striae arising from the anterior two-thirds of its length. Just anterior to the anterior (facial) wall of the MA is a small area of periosteal reaction with faint striae. The affected side exhibits substantial swelling of the face.

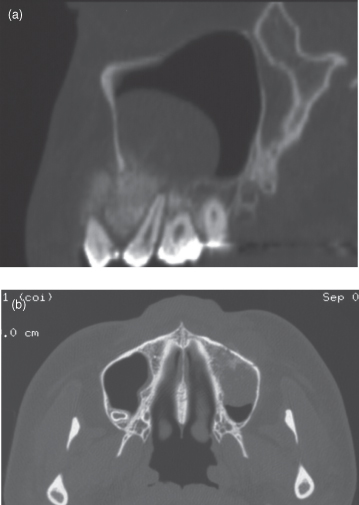

The classical presentation of sinusitis in conventional radiography is thickening of the antral mucosa and the presence of fluid levels. The thickened mucosa in infective sinusitis presents as a radiopaque (of soft-tissue density) band parallel to the bony walls (see Figure 11.7). This may be accompanied with polyps (Figures 11.9, 11.10), particularly in allergy sinusitis. Fluid levels are best seen on a occipitomental projection with the patient sitting upright and with a horizontal beam. It is important to ensure that the petrous temporal bone does not overlie the inferior antrum (Figure 11.11a). The fluid nature of the fluid line can be confirmed by reradiographing following a 30° tilt of the head to one side. Occasionally, if the antral ostium is completely occluded a mucocele can occur resulting in the expansion and erosion of the antral walls. Mucoceles occur more frequently in the frontal and ethmoid sinuses where their close association with the cranium prompts a neurosurgical emergency.

Figure 11.9. Mucositis and antral polyps can occur secondary to an oroantral fistula. Computed tomography of the maxillary antrum (a). This virtual antroscopy (b) displays the MAC suspended from the roof of the antral cavity.

Figure (b) reprinted with permission from MacDonald-Jankowski DS, Li TK. Computed tomography for oral and maxillofacial Surgeons. Part 1: Spiral computed tomography. Asian Journal of Oral Maxillofacial Surgery 2006;18: 68–77.

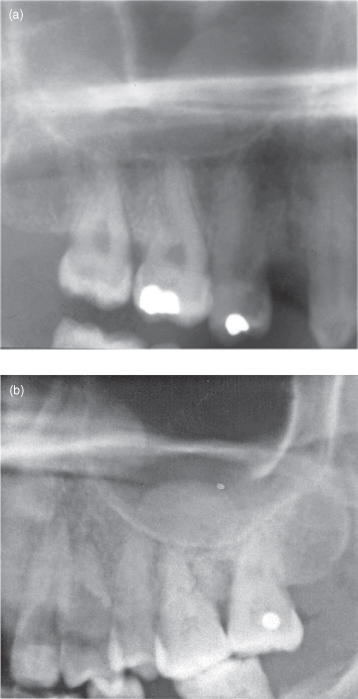

Figure 11.10. Panoramic radiographs from cases displaying polyps arising from the floor of the maxillary antrum.

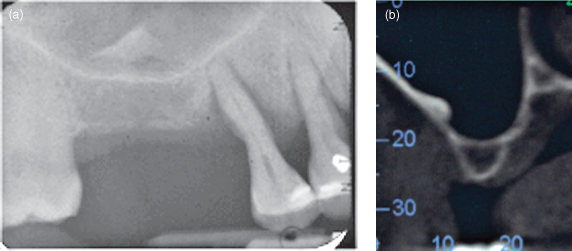

Figure 11.11. Conventional radiography and computed tomography (CT) of a radicular cyst arising in the maxilla’s anterior sextant affecting the maxillary antrum (MA). (a) 30° occipitomental projection displaying complete radiopacity of the left MA. Note that the petrous temporal bone is correctly below the floor of the antrum. There is no obvious buccal expansion, but the medial wall appears to have been displaced into the left nasal cavity. (b) Coronal CT (bone window), at the level of the maxillary canines, exhibits displacement of the lateral and medial walls and the roof of the MA. (c) Axial CT (bone window), through the alveolus, displaying a radiolucency occupying the left anterior region. It is associated with buccal expansion. (d) Axial CT (bone window), through the hard palate, showing an opacification of the entire MA. The anterior wall has been substantially expanded. (e) Axial CT (bone window), at the level of the neck of the condyle, displaying substantial obturation of the antrum by a corticated lesion containing a homogeneous light radiopaque content. The medial wall has been expanded. There is a residual air space at the anteriolateral angle of the MA.

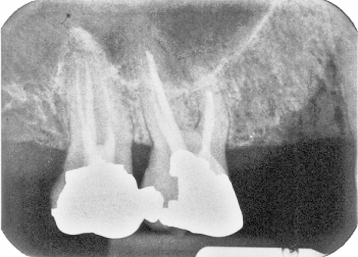

Bacterial sinusitis can arise from a dental origin, for example, from a periapical lesion (see Figure 11.11) or from an oroantral fistula following extraction of a maxillary premolar or molar (see Figure 11.9) Pinhole fistulae are more likely to result in sinusitis rather than a wide fistula, which allows free drainage. Figure 11.12 displays new bone at the apex of a root-filled tooth.

Figure 11.12. Periapical radiograph displaying a root-filled tooth, which exhibits new bone formation at the apex, analogous to the involucrum observed in Figure 10.14.

Antroliths, calcifications within the maxillary antrum, are occasionally observed (Figure 11.13). Such radiopacities may also represent exostoses arising from the antral wall. The latter may be considered when one of the exostosis’ margins appears diffuse rather than sharp (Figure 11.14) or if there has been no change in position over time (Figure 11.15).

Figure 11.13. A periapical radiograph displaying as a nonroot–appearing antrolith within the maxillary antrum. Adjacent to it is an extraction socket.

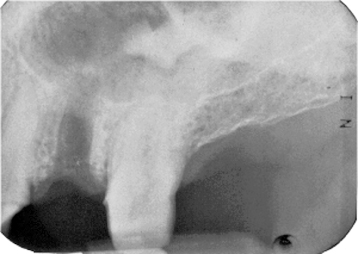

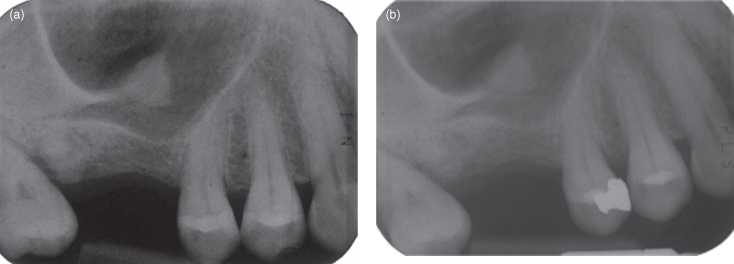

Figure 11.14. Periapical radiography (a) and cone-beam computed tomograph (CBCT; b) of an endostosis within the lateral wall of the maxillary antrum (MA). (a) The superior surfaces are well defined, but the inferior margin is not. (b) The exostosis is on the lateral wall of the MA. The lumen of the MA is otherwise completely normal; that is, the mucosa is not thick enough to be visible and there is no fluid.

Figure 11.15. Periapical radiographs (a and b) taken 3 years apart. They display an antrolith, which has not changed in site and shape during that period. (a) A well-defined radiopacity is sited just distal and superior to the apex of the second premolar. (b) Three years later, the second premolar has acquired an amalgam restoration, but the antrolith has remained unchanged in site and in shape.

Other lesions such as neoplasms and cysts affecting the maxillary antrum are either intrinsic to the antrum (arise within it) or are extrinsic to it (arise outside it) and invade it secondarily. The most frequent intrinsic lesions are mucosal antral cysts (MACs) (Figures 11.16–18). As the MAC represents an accumulation of fluid within the antral mucosa, but without an epithelial lining, it may be referred to as a “pseudocyst.” They vary in frequency in different communities depending upon local climate and culture. They are more frequent in Hong Kong4 than in inner-city London,5 at least during late summer to early autumn when the radiographs were taken. They may also vary within the community according to the seasons. They are dome-shaped and on the panoramic radiography appear to rise most frequently from the antral floor. On helical computed tomography (HCT) they are observed arising from other walls, particularly the lateral wall, which is outside the panoramic radiograph’s focal trough. Although features of periapical pathosis are classically absent in the alveolar bone subjacent to the MACs (Figures 11.16–18), in such situations where a periapical pathosis is present, the antral phenomenon is more likely to represent a mucositis induced by the underlying periapical inflammation rather than to be a MAC.

Figure 11.16. Postcontrast computed tomography (bone window) of a mucosal antral cyst (or pseudocyst). The cyst presents as a soft-tissue density structure partially filling the maxillary antrum. The white “rim” denotes contrast “enhancement” of the surface mucosal rather than a bony cortex as observed in Figure 11.3(d). The surface mucosa of the turbinates are also enhanced (compare with Figure 11.2). Therefore, this is a large mucosal antral cyst rather than a lesion arising within the alveolus (compare with Figure 11.11).

Figure 11.17. The panoramic radiographs of two different mucosal antral cysts (MAC; also called pseudocysts). (a) This MAC is centered upon the maxillary first molar tooth. Although this tooth has a moderate restoration, the likelihood of pulpal necrosis is low. (b) This MAC’s subjacent teeth are undergoing orthodontic treatment and therefore presumably noncarious. There is agenesis of the second premolar.

Reprinted with permission from MacDonald-Jankowski DS. Fibro-osseous lesions of the face and jaws.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses