Dental Public Health Issues in Pediatric Dentistry

Definition of Dental Public Health

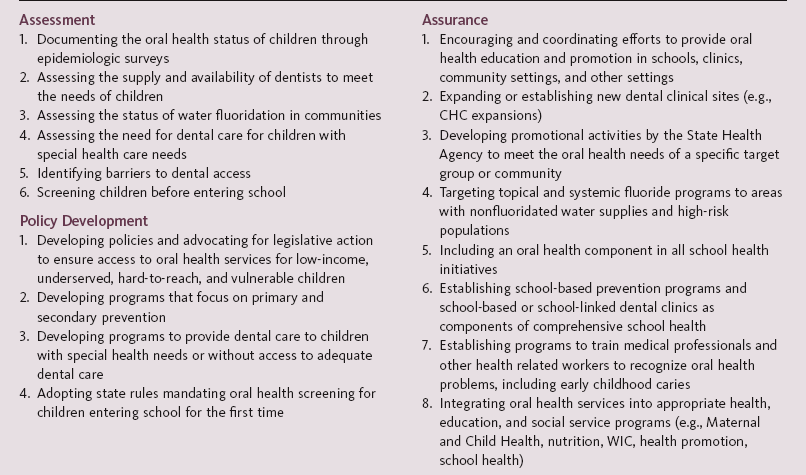

Dental public health is defined as “the science and art of preventing and controlling dental diseases and promoting dental health through organized community efforts.”1 A common misconception about dental public health is that its primary objective is the delivery of dental care to low-income persons. Although this is important, the actual delivery of dental care is only one aspect of dental public health. The three major core functions of public health, as identified by the 1988 Institute of Medicine study, are assessment, policy development, and assurance.2 The major activities of dental public health can be divided into these same categories. Examples of core dental public health activities that affect the oral health of children are given in Box 11-1.

Role of the Individual Practitioner

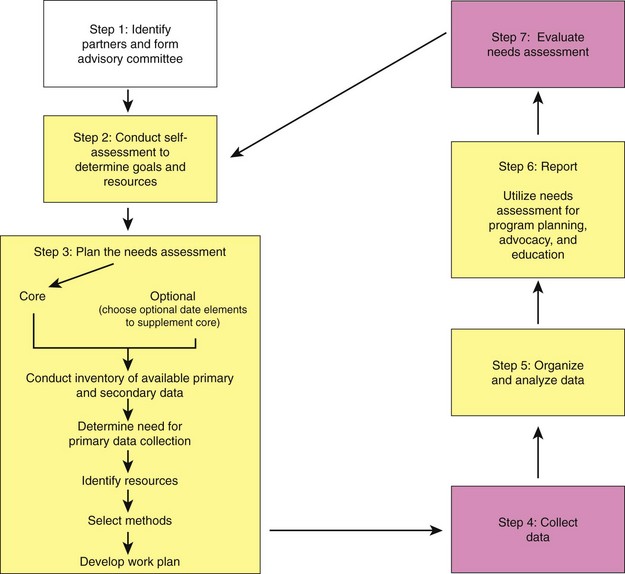

The Association of State and Territorial Dental Directors (ASTDD) developed and disseminated a needs assessment model last revised in 2003, designed to help communities identify and address their oral health needs.3,4 This model is known as the ASTDD Seven-Step Model (Figure 11-1). It provides a straightforward approach for identifying the oral health needs of a community and for designing a program to meet these needs based on available resources. Historically, needs assessments have relied on findings from intraoral examinations, which are typically expensive and time consuming to conduct. The ASTDD model provides an alternative for assessing needs that is more economical and utilizes existing resources and data when available. A community-based needs assessment will also provide an excellent opportunity to educate a community about the importance of oral health.4

FIGURE 11-1 Association of State and Territorial Dental Directors Seven-Step Needs Assessment Model. (Redrawn from the Association of State and Territorial Dental Directors: Assessing oral health needs: ASTDD Seven-Step Model (website). www.astdd.org/oral-health-assessment-7-step-model/. Accessed December 1, 2011.)

FIGURE 11-1 Association of State and Territorial Dental Directors Seven-Step Needs Assessment Model. (Redrawn from the Association of State and Territorial Dental Directors: Assessing oral health needs: ASTDD Seven-Step Model (website). www.astdd.org/oral-health-assessment-7-step-model/. Accessed December 1, 2011.)

Access to Care

Although regular dental care contributes substantially to healthy mouths for millions of children, a significant number of children and adults have serious problems receiving the care they need. These children are most often from low-income or minority families, and unfortunately these groups tend to experience more oral disease than other children.5–7 Some of the factors that can limit access to dental care for these children are (1) lack of finances (including lack of third-party coverage), (2) lack of transportation and geographic isolation, (3) language and cultural barriers, and (4) availability of dental providers who accept Medicaid.

Another major factor that limits use of dental services is lack of perceived need for care and low oral health literacy. Although financial, cultural, behavioral, and biological factors are among the major determinants of oral health, literacy skills are hypothesized to contribute to oral health outcomes. Oral health literacy is defined as “the degree to which individuals have the capacity to obtain, process, and understand basic oral health information and services needed to make appropriate health decisions.”8 Individual patient skills, the provider’s ability to communicate effectively and accurately, and the informational demands placed on patients by health care systems impact health literacy. Low health literacy has been linked to poor health outcomes, lower use of preventive services, increased use of hospital emergency rooms, and higher health care costs.

Dental Participation in Medicaid

Historically, financial limitations have been among the most formidable barriers for low-income children in receiving health care. In 1965, the federal government attempted to reduce these financial barriers by creating the Medicaid program (Title 19), which pays for medical and dental care for eligible low-income children. Adult dental coverage under Medicaid is optional, and covered services vary widely from state to state. However, coverage for child dental services is mandatory because of a 1968 amendment to the Medicaid program creating the Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnostic and Treatment (EPSDT) program.9 The purpose of the EPSDT program is to identify the health problems of children as early as possible and to provide comprehensive preventive and remedial care.

Since 1965, the Medicaid program has been the primary public insurance program for the financing of dental services for low-income children in the United States. Most children below the poverty level who receive dental care do so through the Medicaid (Title 19) program.10 In 1997, the State Children’s Health Insurance Program (SCHIP) was started to expand public insurance to children in families with incomes too high to qualify for Medicaid; the program is now simply known as the CHIP program.11 As of 2006, states have chosen to cover children in their CHIP program either through an expansion of their existing Medicaid program (11 states), a separate child health program (18 states), or a combination of the two (21 states).12

Although Medicaid and CHIP have been successful in improving access to dental services for some, in 1996 a report from the Inspector General of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services indicated that only one in five Medicaid-eligible children receive any dental services annually.13 One of the biggest barriers to dental care is the lack of dentists willing to accept Medicaid-enrolled children. Rates of participation vary by state and by the definition of participation. Since the Inspector General’s report in 1996, improvements in the provision of dental care to children enrolled in Medicaid have occurred. The most substantial improvements in access occurred between 2001 and 2008. In 2001, 27% of children accessed dental services; whereas in 2008, 36% of Medicaid-enrolled children accessed dental services. Though this was a substantial increase, it still means roughly two thirds of Medicaid children did not access dental services in 2008. One concern though is that a growing trend toward Medicaid managed care may result in decreased access. The Government Accountability Office reports that states with Medicaid Managed Care dental programs have much lower levels of children receiving dental services than those states that continue with traditional fee-for-service Medicaid.14

The most common reason cited by dentists for their lack of participation in Medicaid was the low reimbursement rates.15 Other nonfinancial issues, however, were important as well. For example, in a study from Iowa, although dentists were more likely to rank low fees as the most important problem, more dentists said that broken appointments were a more important problem in their practice than low fees.16 Dentists who were less busy and those who believed that dentists have an ethical obligation to treat Medicaid enrollees were most likely to be accepting all new Medicaid patients in their practice. A number of states have increased reimbursement rates to try and improve dentists’ acceptance of Medicaid enrollees. Several other states have been forced to raise Medicaid reimbursement rates after being successfully sued because of poor access to dental care. Michigan chose a different approach and improved dentist participation in Medicaid by “carving out” the dental portion of their Medicaid program in 39 counties to Delta Dental of Michigan to remove the stigma that Medicaid has among dentists and increase reimbursement rates. By 2007, there had been 27 lawsuits in 21 jurisdictions aimed at improving reimbursement rates for dental services in Medicaid.17

However, as of 2011, states face a new challenge because of the troubled U.S. economy. Combined with increasing enrollment in Medicaid and declining federal matching dollars to states, many state legislatures are reducing reimbursement rates for dental care for children and eliminating adult dental services to balance state budgets. These fee reductions for children may result in declining provider participation. Currently, in the 50 states and the District of Columbia, 7 Medicaid programs offer no dental services for adults, 15 offer emergency dental care only, 15 offer limited coverage, and the remaining 14 offer comprehensive services.18 Reducing or eliminating dental services for adults may result in an increase in modeling of poor behavior for children, and evidence clearly shows parental oral health status impacts that of their children.19 As well, in 2011 the Obama administration sided with states in opposing lawsuits against cuts in Medicaid rates that could result in further reductions in access for children and their parents/guardians.20

Federally Qualified Health Centers

Fiscal year (FY) 2010 collections for FQHCs were $7.5 billion. Program statistics from the 2010 Uniform Data System (UDS) for that same year were as follows21:

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses

Outline

Outline Box 11-1

Box 11-1