11

Communications and education for palliative care

INTRODUCTION

New styles of communications and education have been identified as essential components of healthcare generally, but nowhere are they needed so obviously as in the context of managing the healthcare needs of frail elders. Appropriate communication networks are likely to include various health professionals, managers, educators, researchers, and policy makers, especially considering the political dimensions globally of so much of healthcare today (Best, 2010). This chapter will consider the impact of education and communications on the current and potential role of oral healthcare in palliative care.

PALLIATIVE CARE

Palliative care is any form of healthcare or treatment of disease that focuses on reducing the severity of symptoms, rather than curing, halting, or delaying progress of the disease (Merriam Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary, 1993; World Health Organization, 1997). The aim is to prevent or reduce pain and discomfort and to improve quality of life, while affirming life and helping a patient and family to live in dignity with diseases and disabilities.

Hospice care

The hospitium or hospitality in ancient Greece and Rome established a close relationship of caring between the host and a visiting stranger. It evolved through medieval times in the context of the hospice as a philosophy of care and a place of shelter or respite for weary and ill travelers. Its current use stems from the specialized care for dying patients which Dame Cicely Saunders introduced in 1967 at St. Christopher’s Hospice in a suburb of London (Dahlin, 2004). It has developed since then into a program of caring for the physical, spiritual, psychological, and social needs of incurably ill patients and their families. Hospice care includes palliative care. Although not all palliative care is hospice care, they both share similar goals to provide symptom relief and pain management (Wiseman, 2000).

The aim of palliative care in hospice care is to

- help families and patients accept dying as a normal process;

- provide care that neither hastens nor postpones death;

- integrate the psychological and spiritual aspects of care;

- support patients to live as actively as possible and with dignity until death;

- allow families to cope with illness and bereavement;

- provide multidisciplinary healthcare teams to care for patients and their families; and

- help patients and their families select appropriate treatments, and understand and manage clinical side effects.

Metaphysics and spirituality

Medical and nursing schools have recognized for many years the role of communications between mind and matter, and the positive contributions of spirituality to palliative and end-of-life care (Puchalski and Larson, 1998; Pettus, 2002). Spirituality, in contrast to external physical sensations, is a medium of communications between the inner “self” and the surrounding environment, where contemplative introspection occurs in the form of meditation or prayer. Advocates of spiritual communications are reacting typically to the dominance of scientific technology and cure-oriented healthcare (Puchalski, 2001). More broadly, they present spirituality as “the way individuals seek and express meaning and purpose” to life (Puchalski et al., 2009). However, practically, it is a very important form of communication for some patients, especially near the end-of-life where it can help immensely with decisions about healthcare and quality of life (McCord et al., 2004; Balboni et al., 2007). It shores up relationships, and allows patients and clinicians to communicate together collaboratively on treatment and care. Religion as a formal organization of spiritual beliefs, texts, rituals, and other formalities helps many people to conceptualize and express their spirituality in a particular way, whereas others gain similar comfort from a more personal introspection (Sulmasy, 2009).

Serious illness triggers questions about values and relationships. Dentists can help patients with serious illness by listening sympathetically and sensitively, and by alleviating pain and discomfort. This “empathetic witnessing” is beginning to infiltrate dental curricula generally, although not without a struggle, as a counter to the more traditional instrumental approach to dentistry (Khatami et al., 2008).

ORAL HEALTH IN PALLIATIVE CARE

It is unusual for dentists to attend to dying patients. Nonetheless, they offer an invaluable service to palliative care when the mouth is disturbed directly by the diseases or indirectly by treatments. Consequently, the focus of dentistry in palliative care is on quality of life (Larue et al., 1994). Patients want to eat and talk comfortably, to feel clean and at ease with their appearance, and of course to be free of pain (MacEntee, 2006; Brondani et al., 2007). Even patients who are fed through a gastrointestinal feeding tube value the role of anterior teeth in speech, normal appearance, and personal dignity.

Unfortunately, dental services are not part of the health benefits in many countries (Lapeer, 1990; Leake, 2000); consequently, dentists and other dental professionals play a very minor, if any, role on the interdisciplinary care teams that constitute the backbone of communications in most long-term care facilities.

Communications between members of an interdisciplinary healthcare team can take various forms (British Medical Association 2004; Rider et al., 2006). Verbal communications dictate mediation, negotiation, and advocacy. However, nonverbal communications are very pertinent to the success of clinical practice within interdisciplinary teams, especially in multicultural societies. Effective teams acknowledge the diversity of working cultures and professional languages that permeate most interdisciplinary teams in Western society today. There is also a skill to communicating with healthcare managers and administrators, and maneuvering effectively through the organizational hierarchy of a nursing facility. Dental professionals as lone practitioners are usually unfamiliar with these communication tactics, and so they often feel unwelcome or even threatened by the stance of administrators and other team members (Thorne et al., 2001). On a broader perspective, they need to communicate also with professional and governmental bodies, such as dental associations and health ministries, to promote policy change.

Clinical competencies for palliative care

Wiseman (2006) has identified several competencies that are especially relevant to palliative care where dentists need to

- prevent and manage oral mucositis and stomatitis, xerostomia, and candidiasis;

- manage nausea and vomiting;

- cope with the influence of depression and adverse effects of psychotropic drugs on oral care;

- help dieticians with nutrition, hydration, and taste disorders; and

- prevent and manage oral diseases.

Xerostomia, caries, gingivitis, mucosal ulceration, denture-induced trauma, along with disturbances of taste and swallowing are common findings in frail patients as they near death (Jobbins et al., 1992; Wyche and Kerschbaum, 1994; Chiodo et al., 1998; Paunovich et al., 2000). Unfortunately, hospice administrators, physicians, and nurses are very prone to underestimate the prevalence of oral concerns among their frail patients (Andersson et al., 2007). Indeed, medical care teams in general usually overlook the significance of teeth as an integral part of social communications and body image, and only a very small proportion of nursing administrators place any significance on the daily oral hygiene or mouth problems of their patients (Ettinger, 2000; Cohen-Mansfield and Lipson, 2002; MacEntee, 2005).

Clinical scenario

Mr. Franklin is aged 77 years, divorced, and lives in a long-term care center in a small town. His daughter has power of attorney over his affairs, and he has a “living will” with a “Do-Not-Resuscitate” and a “No-Tube-Feeding” directive.

He complains that his denture, which he usually wears day and night, is loose, his mouth is sore and dry, and he cannot eat comfortably. He was very annoyed also that he had difficulty eating the cookies that were a frequent treat during the day but especially before bed and when he could not sleep. He had been advised to reduce his sugar consumption, but he found this difficult.

He has several major health problems: congestive heart failure, diabetes mellitus type II, osteoarthritis, severe hearing loss, hypothyroidism, peroneal muscle atrophy, right total hip replacement, venous insufficiency, diabetic neuropathy, spinal stenosis, and muscular dystrophy. However, he can stand with help but needs a wheelchair to move around.

Mr. Franklin, along with his daughter, visited Dr. Aloysius, his dentist. His daughter told Dr. Aloysius that her father “was failing” and had about 3–6 months to live due to his deteriorating heart and kidneys. Mr. Franklin’s blood pressure at mid-morning of the appointment was 195/98. Neither he nor his daughter could remember whether or not he took his medications that morning, nor did they know his blood sugar levels.

The nurse at the long-term care facility relayed the information to Dr. Aloysius that Mr. Franklin took the following medications daily: levothyroxine—125 mcg qd; acetaminophen—325 mg × 2 qid; aspirin (enteric coated) 325 mg qd; hydrocodone/APAP 5/500 1 tab 4–6 h; furosemide—80 mg qd; gabapentin—300 mg bid; glipizide—5 mg AM; glipizide—10 mg PM; metformin—500 mg bid; novolin—100 u/mL 15 units subcu AM; spirolactone—50 mg qd.

The nurse reported also that his blood pressure was usually high and unstable, and that he had not taken all of his medications that morning.

Mr. Franklin’s mouth on examination revealed that he was cleaning his mouth effectively, and he had several crowns and an upper acrylic partial denture (Figure 11.1).

Figure 11.1 Mr. Franklin’s mouth, teeth, and denture.

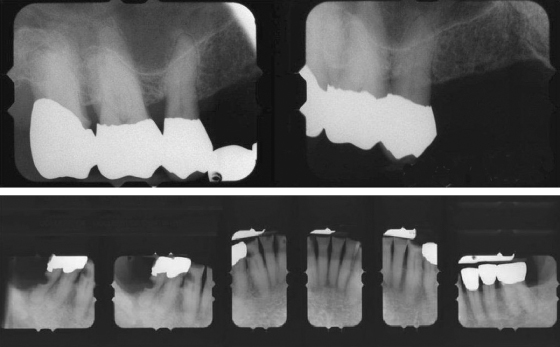

The periodontium of all of the teeth looked secure (Figure 11.2); however, there were carious lesions and a few cavities in several mandibular teeth.

Figure 11.2 Radiographs of Mr. Franklin’s teeth.

The right lateral border of his tongue had leukoplakia, which he was aware of without change for many years, and had been examined by a dermatologist about a year ago. No lymph nodes were palpable one either side of his jaw;

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses