Chapter 10

Root Caries

Dick Gregory and Susan Hyde

School of Dentistry, University of California, San Francisco, CA, USA

Introduction

Dental caries (tooth decay) is a transmissible infection caused by specific bacteria (Streptococcus mutans, Streptococcus sobrinus, lactobacilli, and others) that colonize tooth surfaces, feed on carbohydrates, and produce acids as waste products. These acids dissolve the mineral content of the tooth, and if not halted or reversed, a carious lesion (cavity) is formed (Featherstone et al., 2012).

The risk for dental caries persists throughout life. A dynamic balance exists between pathologic factors that promote caries and protective factors that inhibit it. Pathologic factors include acid-producing bacteria, frequent consumption of fermentable carbohydrates, poor oral hygiene, as well as subnormal salivary flow and composition. Protective factors include normal salivary function, fluoride, daily thorough oral hygiene, casein phosphopeptide-amorphous calcium phosphate paste (GC’s Tooth Mousse®, MI Paste®, and Recaldent®), and extrinsic topical antibacterial substances (Featherstone et al., 2012).

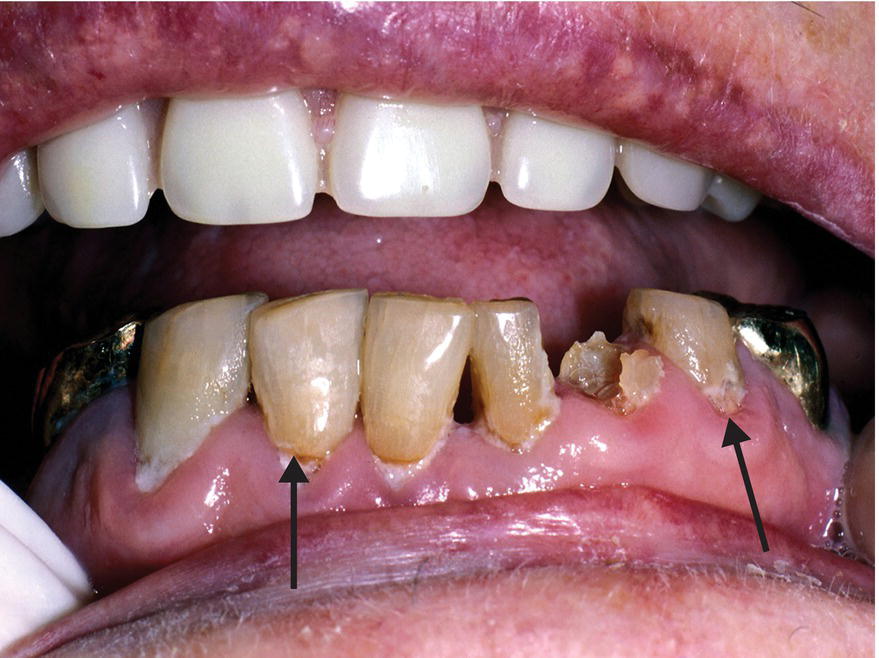

Carious lesions are termed either primary (new lesions on previously unrestored surfaces) (Fig. 10.1) or secondary (new caries around existing restorations) (Fig. 10.2). They occur on the crowns of teeth and exposed root surfaces. Periodontal disease (gum disease), results in loss of gingival (gum) attachment and exposure of the tooth’s root surface. The root comprises the biologic structures cementum and dentin. Root surface cementum and dentin are more susceptible to cavitation because they are less mineralized than enamel, the biologic material that comprises the crown of the tooth, and begin to demineralize at a higher salivary pH.

Figure 10.1 Primary root caries under heavy plaque accumulation: teeth nos. 22–27.

Older adults are retaining an increasing number of natural teeth, and nearly half of all individuals aged over 75 have experienced root caries. Root caries is a major cause of tooth loss in older adults, and tooth loss is the most significant negative impact on oral health-related quality of life for the elderly (Saunders & Meyerowitz, 2005). A false perception exists among dental professionals and policy-makers that dental caries is, for the most part, only active in younger people. Several of the clinical, social, and behavioral changes common to aging predispose older adults to the highest rates of decay are discussed below. The need for improved preventive efforts, and treatment strategies for this population is acute. Better clinical surveillance by public health agencies will drive decisions about oral health policy and education (Dye et al., 2007; Griffin et al., 2004).

Prevalence and risk factors

The prevalence of untreated root caries is 12% for adults aged 65–74 and 17% for those aged over 75 (Dye et al., 2007). African Americans and Mexican Americans experience more oral health problems, including dental caries, throughout the life course. Lower educational attainment is also strongly associated with increased oral health problems at all ages and across all races.

Aging is often associated with changes in oral morphology, chronic systemic disease such as diabetes, and decreasing dexterity, making personal oral hygiene more difficult, particularly for the oldest and most frail individuals. The pain of arthritis and neuropathies make it difficult to grasp or manipulate a manual toothbrush. Patients with dementia experience a higher prevalence of caries than those without dementia, and the rates are related to dementia type and severity. Individuals needing assistance with oral hygiene and whose caregivers have difficulties providing effective oral care experience the highest rates (Rethman et al., 2011).

Another risk factor that often accompanies aging is patients taking multiple medications. More than 500 medications have the potential to decrease salivary flow, which leads to xerostomia (dry mouth) and subsequently dental caries. Other social and behavioral factors that contribute to the higher frequency of root caries in older adults include lack of a perceived need for dental treatment and a history of smoking and alcohol consumption (Featherstone, 2004; Featherstone et al., 2007; ten Cate & Featherstone, 1991).

Good oral hygiene is also compromised by existing dental restorations and the presence of oral prostheses and appliances. Wearing a removable partial denture is associated with higher rates of dental caries. It is unclear whether this is due to the initial high caries rate that resulted in tooth loss or if the denture has a role in causing caries due to increased root surface exposure on the abutment teeth, food impaction, and plaque accumulation.

Caries risk assessment

Understanding factors and behaviors that directly or indirectly impact caries pathogenesis offers opportunities to reduce the caries burden of the aging population. Caries Management By Risk Assessment (CAMBRA) is a conservative and effective approach to prevention and treatment of the disease across the life course (Featherstone, 2004). Caries pathogenesis is recognized as a balance between protective factors (fluoride, calcium phosphate paste, sufficient saliva, and antibacterial agents) and pathologic factors (cariogenic bacteria, inadequate salivary function, poor oral hygiene, and dietary habits – especially frequent ingestion of fermentable carbohydrates) (Featherstone, 2004). Correctly assessing caries risk can identify a therapeutic treatment regimen for effectively managing the disease by reducing pathologic factors and enhancing protective factors, resulting in fewer carious lesions (Featherstone, 2004). With accurate risk assessment, noninvasive care modalities (chlorhexidine rinse and fluoride rinse or varnish) can be used proactively to prevent carious lesions and therapeutically to remineralize early carious lesions. Restorative procedures for more advanced lesions can be conservative, preserving tooth structure and benefiting patient oral health (Featherstone, 2004).

CAMBRA has proven to be a practical caries risk assessment methodology and a systematic and effective approach to caries management. Targeted antibacterial and fluoride therapy based on salivary microbial and fluoride levels has been shown to favorably alter the balance between pathologic and protective caries risk factors. Caries risk assessment with aggressive preventive measures and conservative restoration has been shown to result in a reduced two-year caries increment compared to traditional, nonrisk-based dental treatment. Altering the caries balance by reducing pathologic factors and enhancing protective factors, namely antimicrobial (for example, chlorhexidine) and fluoride rinses, reduced caries risk and resulted in fewer carious lesions. Readers are encouraged to further familiarize themselves with this research and CAMBRA methodology (Featherstone et al., 2012).

For the older adult population the etiology and pathogenesis of dental caries are known to be multifactorial, but the interplay between intrinsic and extrinsic factors is still not fully understood. Caries research commonly tests an intervention for a single pathologic factor; however, it is observed that effective caries control requires a comprehensive and coordinated approach. The predictors of root caries most frequently reported in the literature are caries history, number of teeth, and plaque index (Topping et al., 2009). In addition to the pathologic factors mentioned in the introduction to this chapter, patients with one or more existing carious lesions are at risk for additional new carious lesions in the future (Fig. 10.2). Simply restoring a single lesion does not reduce the bacterial loads in the rest of the mouth.

Figure 10.2 Tooth no. 11 shows secondary caries apical to a root carious lesion previously restored with amalgam.

Dental plaque is a complex biofilm constantly forming and maturing. It consists of microorganisms and extracellular matrix including cariogenic acid-producing bacteria. In high caries-risk individuals the bacterial challenge must be lowered to favorably alter the caries balance. Patients with moderate to high levels of mutans streptococci and lactobacilli require targeted antibacterial treatment and fluoride to combat growth and remineralize tooth surfaces (Featherstone et al., 2012). Recommended regimens are described in the next paragraph.

Evidence-based clinical recommendations generally favor fluoride-containing caries preventive agents; however, chlorhexidine-thymol varnish has also been shown to be effective in the treatment of root caries (Tan et al., 2010). A 38% solution of silver diamine fluoride (SDF) applied annually (Saforide®, Bee Brand Medical, Japan), or 5% sodium fluoride varnish applied every 3 months (Air Force Medical Service, 2007), or 1% chlorhexidine varnish applied every 3 months (Ivoclar Vivadent Corporate, 2014), have all been found more effective in preventing new root caries than giving oral hygiene instruction alone (Slot et al., 2011). Recent recommendations for the prevention of primary root caries called for the professional application of 38% SDF solution annually and 22,500 ppm sodium fluoride varnish applications every 3 months to prevent secondary root caries (Rosenblatt et al., 2009).

There is questionable evidence that xylitol and sorbitol gum can be used as an adjunct for caries prevention (Tan et al., 2010). Cariogenic bacteria prefer six-carbon sugars or disaccharides and are not able to ferment xylitol, depriving them of an energy source and interfering with growth and reproduction. Systematic reviews of clinical trials have not provided conclusive evidence that xylitol is superior to other polyols such as sorbitol (Gluzman et al., 2013) or equal to that of topical fluoride in its anti-caries effect (Mickenautsch & Vengopal, 2012).

Pathologic factors versus protective factors

Diet

A lifetime of caries and/or periodontal disease frequently results in tooth loss. In addition to the reduced masticatory function accompanying tooth loss, it is also common for older adults to experience a diminished ability to taste food. The resultant dietary shift from complex to simple sugars promotes caries. Cariogenic bacteria metabolize sucrose, glucose, fructose, and cooked starches to produce organic acids that dissolve the mineral content of enamel and dentin. The amount, consistency, and frequency of consumption determine the rate and degree of demineralization. Some medications and dietary supplements containing glucose, fructose, or sucrose also contribute to caries risk (Tan et al., 2010).

Genetic susceptibility

There appears to be variation in individual susceptibility to caries. Intrinsic host factors related to the structure of enamel, immunologic response to cariogenic bacteria, and the composition of saliva play key roles in modulating the initiation and progression of the disease. Genetic variation of the host factors may contribute to an increased risk for dental caries; however, the evidence supporting an inherited susceptibility to caries is limited. Utilizing the human genome sequence to improve understanding of a genetic contribution to caries pathogenesis will provide a foundation for future research (Shuler, 2001).

Saliva

Saliva contains many important caries-protective components, such as calcium, phosphate, and fluoride, which are essential to tooth surface remineralization. Salivary proteins and lipids form a protective pellicle on the tooth surface, while other proteins bind calcium, maintaining saliva as a super-saturated mineral solution. Bicarbonate, phosphate, and peptides in saliva provide a critical pH-buffering function. With age, the amount of saliva remains stable; however, saliva becomes thicker due to a reduction in serous flow relative to the mucous component, resulting in decreased lubrication or perceived decreased moistness.

Fluoride

Other than the pre-eruptive mineralization of the developing dentition, systemic benefits of fluoride are minimal. The anti-caries effects of fluoride are primarily topical in adults. The topical effect is described as a constant supply of low levels of fluoride at the biofilm/saliva/dental interface being the most beneficial in preventing dental caries. Therapeutic levels of fluoride can be achieved from drinking fluoridated water and the use of fluoride products (toothpaste, rinse, gel, varnish). Fluoride can inhibit plaque bacterial growth, but more significantly, fluorid/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses