Physiologic Tooth Movement

Eruption and Shedding

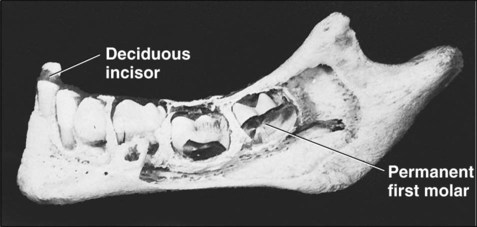

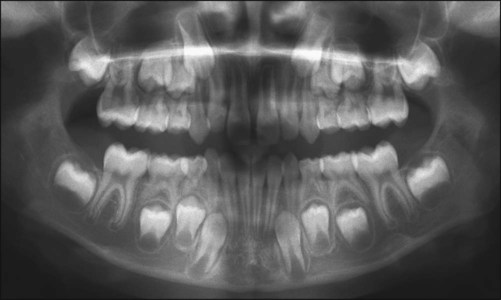

The jaws of an infant can accommodate only a few small teeth. Because teeth, when formed, cannot increase in size, the larger jaws of the adult require not only more but also bigger teeth. This accommodation is accomplished with two dentitions. The first is the deciduous or primary dentition, and the second is the permanent or secondary dentition (Figures 10-1 and 10-2).

The early development of teeth has been described already, and the point has been made that the teeth develop within the tissues of the jaw (Figure 10-3). For teeth to become functional, considerable movement is required to bring them into the occlusal plane. The movements teeth make are complex and may be described in general terms as follows:

Preeruptive tooth movement. Made by the deciduous and permanent tooth germs within tissues of the jaw before they begin to erupt.

Eruptive tooth movement. Made by a tooth to move from its position within the bone of the jaw to its functional position in occlusion. This phase sometimes is subdivided into intraosseous and extraosseous components.

Posteruptive tooth movement. Maintaining the position of the erupted tooth in occlusion while the jaws continue to grow and compensate for occlusal and proximal tooth wear.

Preeruptive Tooth Movement

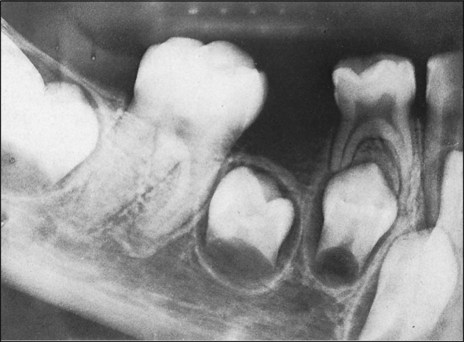

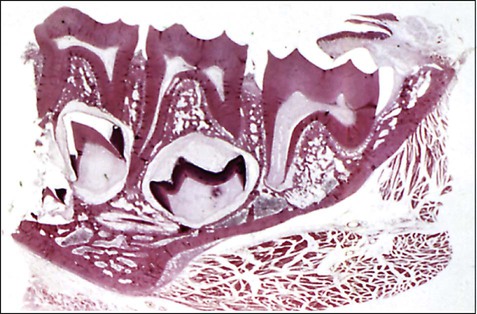

The origin of the successional permanent teeth was described in Chapter 5. Those tooth germs develop on the lingual aspect of their deciduous predecessors, in the same bony crypt. From this position they shift considerably as the jaws develop. For example, the incisors and canines eventually occupy a position, in their own bony crypts, on the lingual side of the roots of their deciduous predecessors, and the premolar tooth germs, also in their own crypts, finally are positioned between the divergent roots of the deciduous molars (Figures 10-4 and 10-5).

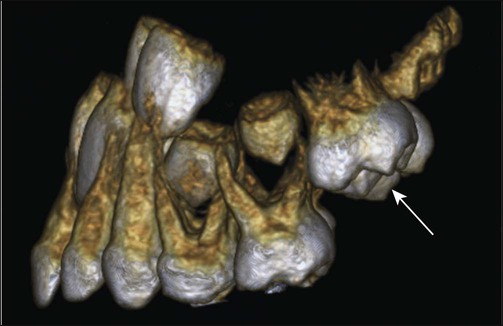

The permanent molar tooth germs, which have no predecessors, develop from the backward extension of the dental lamina. At first, little room is available in the jaws to accommodate these tooth germs. In the upper jaw the molar tooth germs develop first, with their occlusal surfaces facing distally, and then swing into position only when the maxilla has grown sufficiently to provide room for such movement (Figure 10-6). In the mandible the permanent molars develop with their axes showing a mesial inclination, which becomes vertical only when sufficient jaw growth has occurred.

Eruptive Tooth Movement

Histologic Features

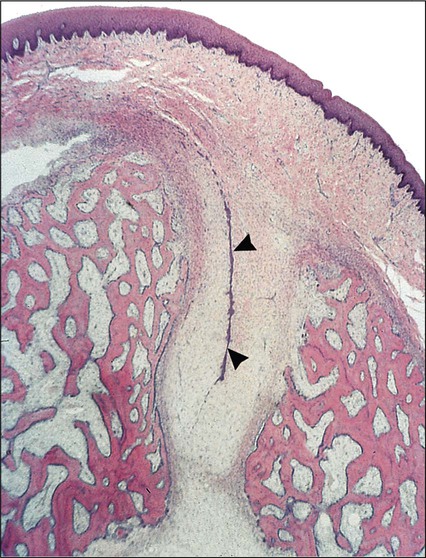

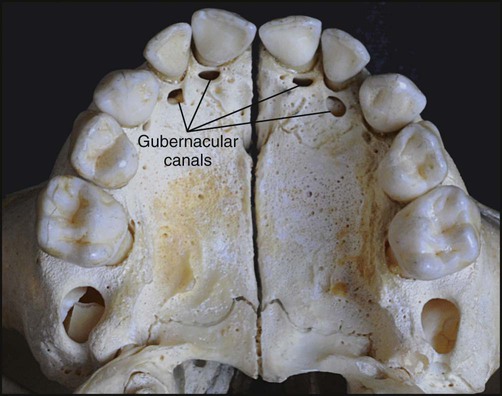

The architecture of the tissues in advance of erupting successional teeth differs from that found in advance of deciduous teeth. The fibrocellular follicle surrounding a successional tooth retains its connection with the lamina propria of the oral mucous membrane by means of a strand of fibrous tissue containing remnants of the dental lamina, known as the gubernacular cord. In a dried skull, holes can be identified in the jaws on the lingual aspects of the deciduous teeth. These holes, which once contained the gubernacular cords, are termed gubernacular canals (Figures 10-7 and 10-8). As the successional tooth erupts, its gubernacular canal is widened rapidly by local osteoclastic activity, delineating the eruptive pathway for the tooth. The rate of eruption depends on the phase of movement. During the intraosseous phase, the rate can attain 10 mm per day; it increases to about 75 mm per day once the tooth escapes from its bony crypt. This rate persists until the tooth reaches the occlusal plane, indicating that soft connective tissue provides little resistance to tooth movement.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses