10

Controversial Issues in Computer – aided Surgical Planning for Craniomaxillofacial Surgery

With the new computer simulation technology, we are able to create three- dimensional (3D) models of the face that incorporate accurate renditions of the teeth, the skeleton, and the soft tissues. Moreover, these models can be oriented to a certain reference head orientation, that is, the natural head position (NHP). From this, one may infer that the value of the physical examination in the clinical decision – making process will become irrelevant, but in our experience, this is far from true. Although these models can capture the anatomy in great detail, they are static and only present the status of the tissues at the time when the image was captured. The physical examination still provides us with extremely valuable dynamic information that cannot be obtained from any other source. To illustrate this, we will discuss several pitfalls that can be encounter by relying only on static images.

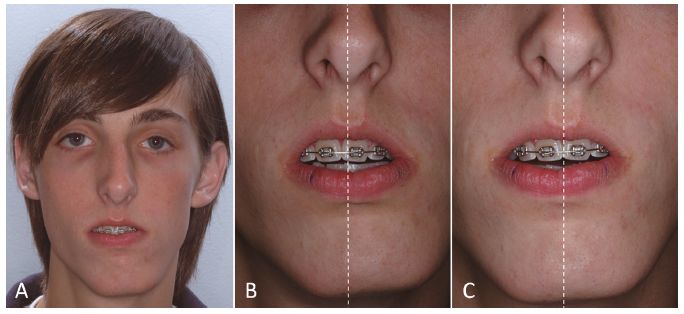

The first example is a patient with significant mandibular laterognathia (lateral chin deviation; Figure 10.1 A). On assessing the alignment of the maxillary dental midline, we have discovered that, in some of these patients, the relationship of the maxillary dental midline to the upper lip varies depending on the mediolateral position of the chin.

During the physical examination, we first measure the transverse alignment of the maxillary dental midline to the middle of the upper lip while the patient is in a centric relationship. In this position, the maxillary dental midline seems to be deviated opposite to chin deviation (Figure 10.1 B). We then measure the same alignment after we have asked the patient to move his chin to the midline, simulating correction of the mandibular asymmetry. In this position, the maxillary dental midline is no longer deviated (Figure 10.1C).

Figure 10.1 The deviation of maxillary dental midline changes depending on different mandibular positions. (A) A patient with significant mandibular laterognathia (lateral chin deviation). (B) The maxillary dental midline seems to be deviated opposite to the chin deviation while the patient is in a centric relationship. (C) The maxillary dental midline is no longer deviated after we have asked the patient to move his chin to the midline simulating correction of the mandibular asymmetry.

What is happening here is that the lateral displacement of the mandible is producing a deformation of the upper lip by dragging it to the side of the chin deviation. When the chin is moved to the midline, the upper lip regains its normal shape. The pitfall here is that if this dynamic deformation is not taken into account, the surgeon will “correct” a maxillary dental midline deviation that is nonexistent. Obviously, this will create an unwanted outcome. Therefore, we recommend that the decision to correct a maxillary midline deviation should be based on physical examination rather than on study images.

Another example of a possible pitfall of simply relying on static images is assessment of the amount of maxillary incisal show. The amount of incisal show varies with the patient’ s position. It tends to decrease when the patient changes position from supine to sitting, and to standing (Figure 10.2).

The measurement of the incisal show on an acquired static image is important, in particular the uncertainty of the functional state of the lips. Ideally, the upper and lower lips should be in repose during the measurement. However, the functional state of the lips is questionable unless the surgeon is present during the scanning. Strained lips will produce an inaccurate determination of the incisal show. In addition, the computed tomography (CT) and cone beam CT (CBCT) images are usually acquired when the patient is biting in occlusion. Therefore, it is best to determine this parameter clinically during the physical examination rather than relying on the computer images.

Figure 10.2 The amount of maxillary incisal show may vary with the patient’ s position. (A) Incisor show in the standing position. (B) Incisor show of the same subject in a supine position.

During the physical examination, this parameter should be measured with the patient standing in front of the surgeon. The decision of how much to change the amount of incisal show should not be based solely on the amount of show at rest. Other important issues should also be taken into account as well. These include the amount of gingival show during smiling, the presence of delayed passive eruption, and the presence of attrition. Finally, clinical measurements of the occlusal cant, degree of dystopia, and ear position also serve to verify that the composite skull model is correctly oriented in the 3D coordinate system.

An important prerequisite for accurate planning is to orientate the 3D composite skull model to a reference position. In two- dimensional (2D) cephalometry, the reference planes are usually the Frankfort horizontal plane and sella – nasion plane. However, many patients with craniomaxillofacial deformities have significant asymmetries of the upper face and skull base, and common intracranial cephalometric landmarks and planes often cannot be used to orient the composite skull model. The use of the NHP obviates the need for intracranial landmarks and provides a reproducible reference framework.

Currently, there is still debate over how to record the NHP and transfer it to the 3D model. The simplest method is to “eyeball” the 3D model in the computer and orient it to a balanced position based on the physician’ s best estimate. Although it is not the patient’ s true NHP, it may work if the craniofacial structures are symmetric. However, when the upper face and skull base have significant asymmetry, this method is more an art than a science. It is the authors’ opinion that NHP should be recorded directly when the patient is in NHP.

Can the NHP be recorded during CT scanning? If a medical CT scanner is used, the patient />

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses