Chapter 1

Problem Solving in the Diagnosis of Odontogenic Pain

Problem-solving challenges and dilemmas in diagnosis addressed in this chapter are:

“A few moments’ consideration of the original cause of trouble at the apex of roots enables us to realize what is required to be accomplished in the way of successful treatment. If the original cause is admitted to be irritation from decomposing pulp, its removal will in most cases affect a cure.”< ?xml:namespace prefix = "mbp" />

Making an accurate endodontic diagnosis is a problem for many dentists. The solution to this problem is neither easy nor lends itself to a method that can be reduced to a series of simple steps. A further complication is that most clinicians find it difficult to challenge long-held concepts and practices and resist the notion that these beliefs may be biased. Their experience, under examination, may be limited. There is also a tendency to place trust in authorities without asking how these authorities came to be dominant influences in clinical thinking and practice. When attending a continuing education course, it is not unusual to have thoughts, such as “I already know this,” or “I have heard this before,” or “There is nothing new to be learned here.”

Dentists attend continuing education courses or read professional literature with the intent to improve their knowledge and abilities. In reality, most of the information in a course may not be new to an experienced clinician. What is often missed by clinicians, however, is the importance of detail, relative significance of concepts, and how this unique information can enhance their diagnostic acumen and clinical data gathering. Upon returning to the practice of dentistry, the information presented in the educational experience is often forgotten, and the clinician is destined to repeat the same errors they have been perpetuating for years. In an attempt to minimize this nonproductive process, and in the hope that ingrained patterns of erroneous thinking in the diagnosis of pulpal and periapical pathosis states will be clarified, simplified, and enhanced for the dental clinician, this chapter will provide detailed diagnostic methods used by the authors and most endodontic specialists.

Most concepts may already be familiar; the intent of this chapter is to provide a context for each method or test that will emphasize its unique importance in a problem-solving format. Not all diagnostic tests, examination methods, weighing of historical information, or patient subjective data are relevant to every case. Through clinical examples, the value of each approach will be emphasized to assist the clinician in reevaluating the entire diagnostic process and the incorporation of a realistic and meaningful approach to making a final diagnosis.

Taking an Accurate Dental History

The most common complaint that brings people to the dentist is pain. It is usually an acute problem termed “an emergency” by the patient, who typically characterizes it as being swollen, having pain to biting, being unable to tolerate temperature changes, or the statement, “I have an infection in my tooth.” Occasionally the dental problem is the result of trauma that is usually obvious by appearance; or the patient arrives with complaints of vague or nonlocalized pain. In some cases, pain may not be a reason for the dental consultation at all. The specific nature of the problem is sorted out during the consultation interview, where patient statements and other critical information are collected. In addition to revealing much information about the dental problem, this initial contact, if done in an open and nonthreatening manner, will usually disclose patients’ expectations, previous experiences, fears, and their understanding of the nature of their dental problem.

Because pain is so variable and its perception so subjective, history taking will require gathering and interpreting appropriate information. Patients frequently have strongly held preconceptions that may not be true or relevant. For example, often they believe they know which tooth is causing the problem. The clinician must be able to distinguish information that is useful, such as “I cannot bite on this tooth,” from that which is subjective, such as “The pain hurts me in these three teeth.” It is highly unlikely there are three teeth creating the patient’s problem, but it is quite common for pain to be referred to an area larger than the area of the offending tooth. A few pertinent questions to obtain greater insight into the patient’s specific problem may include:

In some cases, pain has continued after another clinician has attempted to manage the patient’s problem. In these cases, the following questions may be appropriate.

Hearing the patient describe their pain is essential to understanding their problem, interpreting the information gathered, and asking additional probing questions when necessary. Some patients may be accompanied by a spouse, parent, or friend who wishes to contribute to the interview. Generally, this is not very helpful. It is best to address the patient for this information.

At this point, it is appropriate to ask the patient about any physical perceptions or concerns.

Interpretation of Historical Data and Subjective Findings

Interpreting historical data and subjective findings usually occurs simultaneously as they are secured, and these initial impressions usually direct the subsequent questioning. As a broad overview, let us consider these questions in the order they have been presented. Responses to the initial questions about the basic dental complaint can often lead directly to a clinical examination and a rapid diagnosis. If the problem were an acute abscess, for example, the patient would probably give enough information in the first two or three sentences to make a tentative diagnosis of abscess. Subsequent questioning would then concentrate on the presence of physical signs and symptoms of infection. It would remain to be determined if the abscess is of pulpal, periodontal, or other etiology.

Patients who have been experiencing chronic pain problems may not be feeling any pain at the moment of examination but can describe the chronic nature of it in detail. Endodontic problems can develop episodically over a period of time but will most often show a pattern of decreasing periods of comfort and increasing periods of discomfort. This may even be followed by periods of complete comfort.

The overall time frame for tooth problems is much shorter than for myofascial pain problems, which often come and go over a period of years. It is helpful to find out if there have been periods of complete resolution. This kind of history is also consistent with myofascial pain related to nocturnal bruxing or clenching, which is discussed in

If the patient has not experienced appreciable pain, responses to the probing questions during data gathering often focus on a nodule or “bump” noticed on the mucosal surface or an area that is noticeably tender to touch. These findings may indicate a developing periapical lesion or a draining sinus tract. Other possibilities could include a wide range of possibilities, from a normal but previously unrecognized exostosis to a small swelling associated with blocked ducts of minor or major (Stensen’s duct) salivary glands. Diagnosis and treatment of many of these etiologies is beyond the intended scope of this book. Our purpose here is to rule these out as having a pulpal or periapical origin or focus.

Finally, some patients who come for a routine examination are found to have a clinical lesion of possible pulpal or periapical origin or a radiographic lesion discovered on the routine radiographic survey (see

Clinical Examination: Objective Findings

Visual Inspection

Clinical examination specifically for an endodontic diagnosis will focus on two areas: causative factors in the teeth (pulpal inflammation, infection, etc.) and signs of periapical pathosis in the soft tissues due to spread of an inflammatory/infectious process from the pulp.

CLINICAL PROBLEM

Problem

A 52-year-old male was seen on an emergency basis. His chief complaint was of acute, spontaneous pain episodes in the mandibular left molar area (

Solution

Failure to reproduce the patient’s chief complaint during the examination of this quadrant of teeth resulted in conducting further tests in other areas of the left side. Further tests were then conducted on the opposing teeth. The heat test elicited an acute, severe painful response on the maxillary second molar. A radiograph of this area revealed gross caries (see

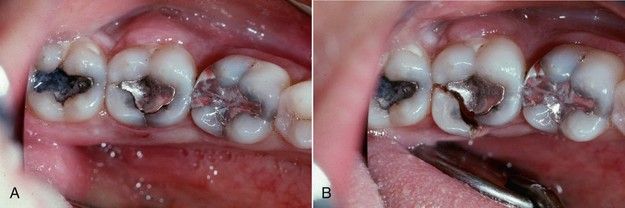

Another important process in the clinical examination is to search for the presence of coronal fracture lines.

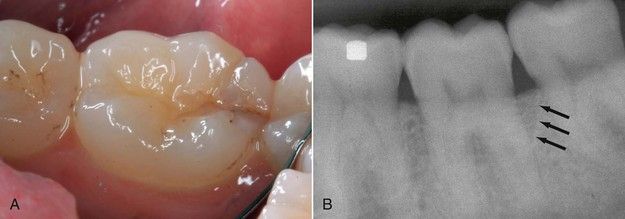

FIGURE 1-2 Coronal fracture evident on intact marginal ridges. The mesial fracture line is obvious (black arrows). The distal extension of the same fracture is not as apparent but is visible (red arrow).

FIGURE 1-3 A, Coronal fracture extending over distal marginal ridge. B, Periodontal defect from extension of crack below crestal bone (arrows).

FIGURE 1-4 A, Fracture lines evident on distal marginal ridge and lingual developmental groove of mandibular second molar. B, In this case, the fracture resulted in complete separation of the cusp from the crown.

The soft tissues should be examined for physical signs of redness and swelling that may indicate that the periapical tissues have become inflamed or infected. Typically these specific physical signs would be evidence of a sinus tract, local swelling over the apices, or regional swelling (

Occasionally there may be signs of infection that are likely to be the source of the patient’s complaint but unlikely to be of pulpal or periapical origin. Pericoronitis around a partially erupted third molar is usually recognizable owing to its location; an endodontic problem with the second molar may have to be ruled out (

The clinical examination is conducted with a series of instruments and techniques that might be considered the “tools of problem solving.” Each test or assessment technique can reveal a clue that may impact or confirm the ultimate diagnosis. Seldom will it be necessary to do all of the tests or techniques listed, but it is equally important not to jump to conclusions too early in difficult diagnostic cases. The process of clinical examination is intended to both identify the source of the symptoms or observed pathosis and to rule out pathosis on adjacent teeth. It may be difficult in some cases to reproduce reported symptoms, but it often will be possible to reach a confident opinion about the normality of certain teeth, thereby reaching a diagnosis through the process of elimination.

During a clinical examination, data are gathered using a multitude of tests and evaluative procedures. While some tests will focus on the status of the pulp, others will be used to ascertain the extent of the spread of pulp inflammation or infection to the supporting periodontium. At times, it is difficult to separate information that is pulpally related from information related to extension of the disease process or periapically related. It is the intent of this first chapter to focus on the gathering of key information that will initially provide evidence of pulpal status. Other findings gleaned in this problem-solving process must be correlated and integrated with a thorough examination of the supporting periodontium, along with quality radiographs. These data will then be integrated into a periapical diagnosis that will be addressed in

Use of the Explorer

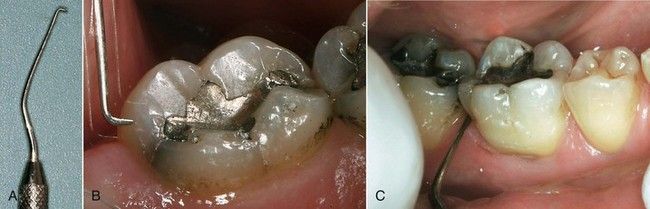

For diagnostic purposes, the No. 23 explorer or the DG16 endodontic explorer (both explorers can feature a No. 17 tip when the instruments are double ended) are useful for the detection of caries, open restorative margins, fractures, loose cusps, and fracture lines (

Palpation

One of the most informative but often overlooked evaluative procedures of the clinical examination is palpation. While not crucial for a pulpal diagnosis, for teeth with pulpal necrosis, palpation soreness or pain may reveal the presence of inflammation associated with periapical periodontitis.

Percussion

Pain or tenderness to tapping on a tooth (percussion) is not crucial to a pulpal diagnosis but is symptomatic of three other conditions. It may be a sequela of trauma, which applies to virtually all anterior teeth and is easy to identify by the history. A root canal procedure may not be indicated, because there may be no pulpal damage. Sensibility testing (formerly known as vitality testing) would be indicated. There may or may not be concomitant palpation tenderness with traumatized teeth, but if palpation tenderness is found, it will usually not be confined to the region over the apex.

Second, tenderness to percussion may be the result of periapical inflammation due to either a necrotic or an acutely inflamed pulp.

Third, tenderness to percussion may be a symptom of occlusal trauma, most often the result of nocturnal clenching or bruxing.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses