Malocclusion and Dentofacial Deformity in Contemporary Society

The Changing Goals of Orthodontic Treatment

Crowded, irregular, and protruding teeth have been a problem for some individuals since antiquity, and attempts to correct this disorder go back at least to 1000 BC. Primitive (and surprisingly well-designed) orthodontic appliances have been found in both Greek and Etruscan materials.1 As dentistry developed in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, a number of devices for the “regulation” of the teeth were described by various authors and apparently used sporadically by the dentists of that era.

After 1850, the first texts that systematically described orthodontics appeared, the most notable being Norman Kingsley’s Oral Deformities.2 Kingsley, who had a tremendous influence on American dentistry in the latter half of the nineteenth century, was among the first to use extraoral force to correct protruding teeth. He was also a pioneer in the treatment of cleft palate and related problems.

To make good prosthetic replacement teeth, it was necessary to develop a concept of occlusion, and this occurred in the late 1800s. As the concepts of prosthetic occlusion developed and were refined, it was natural to extend this to the natural dentition. Edward H. Angle (Figure 1-1), whose influence began to be felt about 1890, can be credited with much of the development of a concept of occlusion in the natural dentition. Angle’s original interest was in prosthodontics, and he taught in that department in the dental schools at Pennsylvania and Minnesota in the 1880s. His increasing interest in dental occlusion and in the treatment necessary to obtain normal occlusion led directly to his development of orthodontics as a specialty, with himself as the “father of modern orthodontics.”

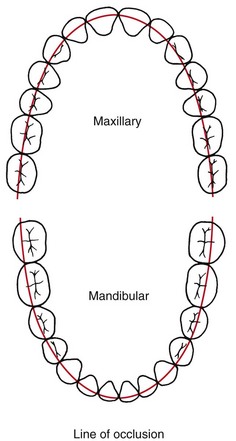

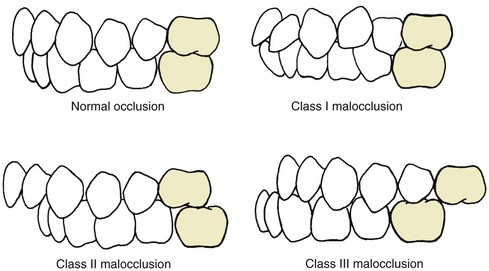

Angle’s classification of malocclusion in the 1890s was an important step in the development of orthodontics because it not only subdivided major types of malocclusion but also included the first clear and simple definition of normal occlusion in the natural dentition. Angle’s postulate was that the upper first molars were the key to occlusion and that the upper and lower molars should be related so that the mesiobuccal cusp of the upper molar occludes in the buccal groove of the lower molar. If the teeth were arranged on a smoothly curving line of occlusion (Figure 1-2) and this molar relationship existed (Figure 1-3), then normal occlusion would result.3 This statement, which 100 years of experience has proved to be correct—except when there are aberrations in the size of teeth, brilliantly simplified normal occlusion.

Class I: Normal relationship of the molars, but line of occlusion incorrect because of malposed teeth, rotations, or other causes

Class II: Lower molar distally positioned relative to upper molar, line of occlusion not specified

Class III: Lower molar mesially positioned relative to upper molar, line of occlusion not specified

Note that the Angle classification has four classes: normal occlusion, Class I malocclusion, Class II malocclusion, and Class III malocclusion (see Figure 1-3). Normal occlusion and Class I malocclusion share the same molar relationship but differ in the arrangement of the teeth relative to the line of occlusion. The line of occlusion may or may not be correct in Class II and Class III.

The changes in the goals of orthodontic treatment, which are to focus on facial proportions and the impact of the dentition on facial appearance, have been codified now in the form of the soft tissue paradigm.4

Modern Treatment Goals: The Soft Tissue Paradigm

A paradigm can be defined as “a set of shared beliefs and assumptions that represent the conceptual foundation of an area of science or clinical practice.” The soft tissue paradigm states that both the goals and limitations of modern orthodontic and orthognathic treatment are determined by the soft tissues of the face, not by the teeth and bones. This reorientation of orthodontics away from the Angle paradigm that dominated the twentieth century is most easily understood by comparing treatment goals, diagnostic emphasis, and treatment approach in the two paradigms (Table 1-1). With the soft tissue paradigm, the increased focus on clinical examination rather than examination of dental casts and radiographs leads to a different approach to obtaining important diagnostic information and that information is used to develop treatment plans that would not have been considered without it.

TABLE 1-1

Angle Versus Soft Tissue Paradigms: A New Way of Looking at Treatment Goals

| Parameter | Angle paradigm | Soft tissue paradigm |

| Primary treatment goal | Ideal dental occlusion | Normal soft tissue proportions and adaptations |

| Secondary goal | Ideal jaw relationships | Functional occlusion |

| Hard/soft tissue relationships | Ideal hard tissue proportions produce ideal soft tissues | Ideal soft tissue proportions define ideal hard tissues |

| Diagnostic emphasis | Dental casts, cephalometric radiographs | Clinical examination of intraoral and facial soft tissues |

| Treatment approach | Obtain ideal dental and skeletal relationships, assume the soft tissues will be OK | Plan ideal soft tissue relationships and then place teeth and jaws as needed to achieve this |

| Function emphasis | TM joint in relation to dental occlusion | Soft tissue movement in relation to display of teeth |

| Stability of result | Related primarily to dental occlusion | Related primarily to soft tissue pressure/equilibrium effects |

1. The primary goal of treatment becomes soft tissue relationships and adaptations, not Angle’s ideal occlusion. This broader goal is not incompatible with Angle’s ideal occlusion, but it acknowledges that to provide maximum benefit for the patient, ideal occlusion cannot always be the major focus of a treatment plan. Soft tissue relationships, both the proportions of the soft tissue integument of the face and the relationship of the dentition to the lips and face, are the major determinants of facial appearance. Soft tissue adaptations to the position of the teeth (or lack thereof) determine whether the orthodontic result will be stable. Keeping this in mind while planning treatment is critically important.

2. The secondary goal of treatment becomes functional occlusion. What does that have to do with soft tissues? Temporomandibular (TM) dysfunction, to the extent that it relates to the dental occlusion, is best thought of as the result of injury to the soft tissues around the TM joint caused by clenching and grinding the teeth. Given that, an important goal of treatment is to arrange the occlusion to minimize the chance of injury. In this also, Angle’s ideal occlusion is not incompatible with the broader goal, but deviations from the Angle ideal may provide greater benefit for some patients, and should be considered when treatment is planned.

3. The thought process that goes into “solving the patient’s problems” is reversed. In the past, the clinician’s focus was on dental and skeletal relationships, with the tacit assumption that if these were correct, soft tissue relationships would take care of themselves. With the broader focus on facial and oral soft tissues, the thought process is to establish what these soft tissue relationships should be and then determine how the teeth and jaws would have to be arranged to meet the soft tissue goals. Why is this important in establishing the goals of treatment? It relates very much to why patients/parents seek orthodontic treatment and what they expect to gain from it.

The Usual Orthodontic Problems: Epidemiology of Malocclusion

In the United States, two large-scale surveys carried out by the U.S. Public Health Service (USPHS) covered children ages 6 to 11 years between 1963 and 1965 and youths ages 12 to 17 years between 1969 and 1970.5,6 As part of a large-scale national survey of health care problems and needs in the United States in 1989-1994 (National Health and Nutrition Estimates Survey III [NHANES III]), estimates of malocclusion again were obtained. This study of some 14,000 individuals was statistically designed to provide weighted estimates for approximately 150 million persons in the sampled racial/ethnic and age groups. The data provide current information for U.S. children and youths and include the first good data set for malocclusion in adults, with separate estimates for the major racial/ethnic groups.7

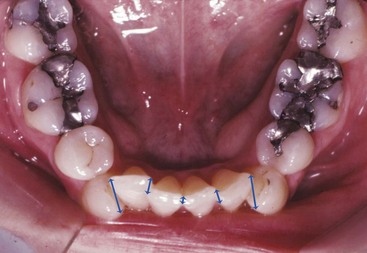

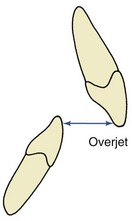

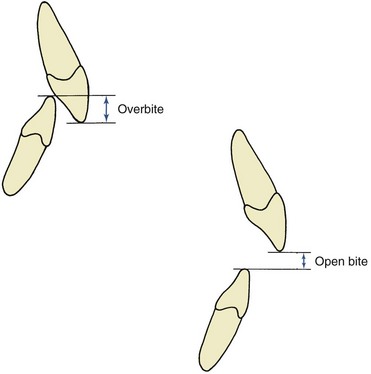

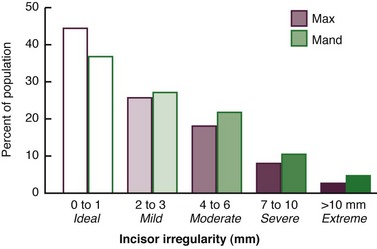

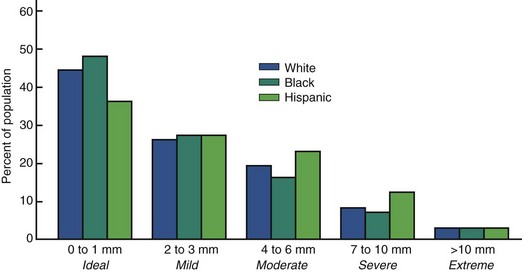

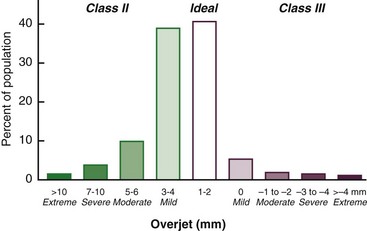

The characteristics of malocclusion evaluated in NHANES III included the irregularity index, which is a measure of incisor alignment (Figure 1-4); the prevalence of midline diastema larger than 2 mm (Figure 1-5); and the prevalence of posterior crossbite (Figure 1-6). In addition, overjet (Figure 1-7) and overbite/open bite (Figure 1-8) were measured. Overjet reflects Angle’s Class II and Class III molar relationships. Because overjet can be evaluated much more precisely than molar relationship in a clinical examination, molar relationship was not evaluated directly.

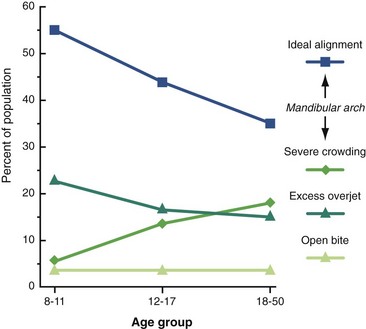

Current data for these characteristics of malocclusion for children (age 8 to 11), youths (age 12 to 17), and adults (age 18 to 50) in the U.S. population, taken from NHANES III, are displayed graphically in Figures 1-9 to 1-11.

Note in Figure 1-9 that in the age 8 to 11 group, just over half of U.S. children have well-aligned incisors. The rest have varying degrees of malalignment and crowding. The percentage with excellent alignment decreases in the age 12 to 17 group as the remaining permanent teeth erupt, then remains essentially stable in the upper arch but worsens in the lower arch for adults. Only 34% of adults have well-aligned lower incisors. Nearly 15% of adolescents and adults have severely or extremely irregular incisors, so that major arch expansion or extraction of some teeth would be necessary to align them (see Figure 1-9).

A midline diastema (see Figure 1-5) often is present in childhood (26% have >2 mm space). Although this space tends to close, over 6% of youths and adults still have a noticeable diastema that compromises the appearance of the smile. Blacks are more than twice as likely to have a midline diastema than whites or Hispanics (p < .001).

Occlusal relationships must be considered in all three planes of space. Posterior crossbite reflects deviations from ideal occlusion in the transverse plane of space. It is relatively rare at all ages. Overjet or reverse overjet indicates anteroposterior deviations in the Class II/Class III direction, and overbite/open bite indicates vertical deviations from ideal. Overjet of 5 mm or more, suggesting Angle’s Class II malocclusion, occurs in 23% of children, 15% of youths, and 13% of adults (Figure 1-12). Reverse overjet, indicative of Class III malocclusion, is much less frequent. This affects about 3% of American children and increases to about 5% in youths and adults. Severe or extreme Class II and Class III problems, at the limit of orthodontic correction or too severe for nonsurgical correction, occur in about 4% of the population, with severe Class II much more prevalent. Severe Class II problems are less prevalent and severe Class III problems are more prevalent in the Hispanic than the white or black groups.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses