15 Sialadenitis and Sialadenosis—Interventional Sialendoscopy

Indications and Patient Selection

Patient Information and Consent

Cannulas (Double-Flow with Working Channel)

Standard Procedure for Salivary Stones

Treating Salivary Duct Stenosis

Preoperative Extracorporeal Lithotripsy

Impacted Stone with Dormia Basket

Pharyngeal Infiltration and Large Parotid Swelling in Juvenile Recurrent Parotitis Treatment

Permanent Intraductal Stenting

Introduction

Almost immediately after the introduction of diagnostic sialendoscopy,1 it became apparent that the method would not only make the diagnosis of salivary pathologies more accurate, but that it should also be possible to perform treatments and manipulation of the salivary ductal system at the same time. Ever since the first large series on interventional sialendoscopy were published more than 10 years ago,2,3 new technical devices expanding the ability to perform more innovative maneuvers in interventional sialendoscopy have been reported each year.

The public has also become aware of these improvements in sialendoscopy techniques and is expecting minimally invasive interventions to be offered as the first treatment option when surgery is necessary for salivary gland disorders. It is currently almost always possible to use interventional sialendoscopy to correct abnormalities of the salivary ductal system, while at the same time maintaining or restoring salivary gland function. Occasionally, when more complex pathologies are encountered, a combined approach may be necessary—e.g., combining interventional sialendoscopy with open surgery to allow preservation of the salivary gland, while at the same time minimizing the extent of surgery and consequently the associated morbidity for the patient.

Definition

To be able to carry out interventional sialendoscopy as a skilled surgical procedure, the clinician must first become proficient in the techniques of diagnostic sialendoscopy (see Chapter 9). The surgeon’s ideal is to be able to perform diagnostic and therapeutic procedures in sequence in a single session.4 If a salivary stone or duct stenosis is diagnosed as the cause of the patient’s symptoms and is confirmed at diagnostic sialendoscopy, then interventional sialendoscopy skills can allow the stone or stenosis to be dealt with in the same time slot allocated for the procedure.

Interventional sialendoscopy is the natural second step after diagnostic sialendoscopy. It can be performed during the same procedure.

Interventional sialendoscopy is the natural second step after diagnostic sialendoscopy. It can be performed during the same procedure.

Indications and Patient Selection

The majority of indications for interventional sialendoscopy are in patients suffering from either sialolithiasis or stenosis of the salivary ductal system.

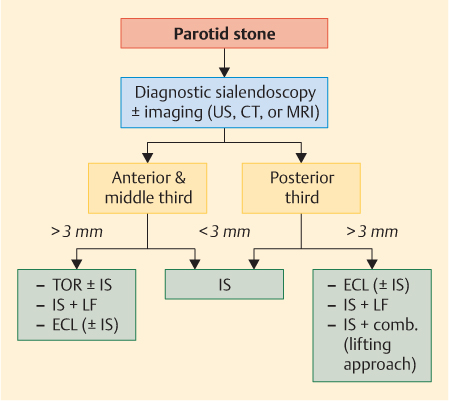

Fig. 15.1 Decision-making algorithm for the treatment of parotid stones. Comb., combined technique (open surgery and interventional sialendoscopy); CT, noncontrast computed tomography; ECL, extracorporeal lithotripsy; IS, interventional sialendoscopy; LF, laser fragmentation; TOR, transoral removal; US, ultrasound.

Sialolithiasis

Sialolithiasis

With the developments and improvements in interventional sialendoscopy since its introduction into sialendoscopy in the management of sialolithiasis, the indications for interventions are continuing to expand as newer techniques and instruments are developed.

Sialolithiasis is the main indication for interventional sialendoscopy, especially for the submandibular glands.

Sialolithiasis is the main indication for interventional sialendoscopy, especially for the submandibular glands.

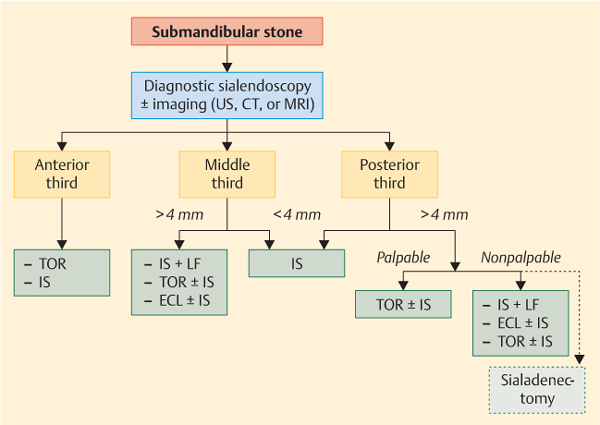

The decision-making algorithms (Figs. 15.1 and 15.2) show the steps involved in treatment and management.

The indications for sialolith removal are still changing thanks to the continuing development of the available techniques. The algorithm is also helpful for grasping the criteria for optimal decision-making in patients with salivary gland stones:

Involved gland: parotid or submandibular gland

Involved gland: parotid or submandibular gland

Location in the duct: stone diameters in the distal, middle, and proximal or intraglandular thirds: about 3 mm diameter for the Stensen duct about 4 mm diameter for the Wharton duct

Location in the duct: stone diameters in the distal, middle, and proximal or intraglandular thirds: about 3 mm diameter for the Stensen duct about 4 mm diameter for the Wharton duct

Available equipment: interventional sialendoscopes, dedicated laser, extracorporeal lithotripter

Available equipment: interventional sialendoscopes, dedicated laser, extracorporeal lithotripter

Fig. 15.2 Decision-making algorithm for the treatment of submandibular stones. CT, noncontrast computed tomography; ECL, extracorporeal lithotripsy; IS, interventional sialendoscopy; LF, laser fragmentation; TOR, transoral removal; US, ultrasound.

Salivary Duct Stenosis

Salivary Duct Stenosis

The decision-making algorithm for managing patients with salivary stones is simple in comparison with the one for ductal stenosis. A suggested LSD classification—lithiasis (stones), stenosis, and dilation—has been published and is currently being used by many clinicians.5 At present, however, there is no agreed consensus for the diagnosis and treatment of salivary duct stenosis.

It would seem logical when treating salivary duct stenosis to commence with a technique that is less traumatic initially, such as dilation using the sialendoscope itself, progressing to using bougies and ultimately miniballoon dilation. These procedures are curative when a minor stenosis is present (LSD classification S1 and S2; see Table 9.1). In more advanced stenosis (LSD S3 or S4), such maneuvers rarely work, and a more aggressive surgical approach is required, with a termino-terminal graft technique that uses a venous or arterial graft to replace the duct stenosis. As is to be expected, such aggressive surgical approaches are associated with greater morbidity as result of the combined approach as well as potential damage to the facial nerve. Some surgeons recommend permanent stenting of the repaired segment, as the risk of recurrent stenosis persists lifelong after this type of operation.

Juvenile Recurrent Parotitis

Juvenile Recurrent Parotitis

The pathological physiology of juvenile recurrent parotitis is unknown.6 A typical white appearance and lack of vascularity in the ductal layer has been described.7 This lack of vascularity in the ductal layer interferes with the sphincter system and with the ductal system’s ability to drain saliva, leading to stricture formation, ductal obstruction, and chronic infection of the parotid gland. In an analysis of 70 patients with juvenile recurrent parotitis who were treated with sialendoscopic lavage using a steroid solution, there was no recurrence of symptoms in more than 93% of the patients who were followed up for 6–36 months.

Interventional sialendoscopy has been validated as a safe technique in children with sialolithiasis of whatever age and is reported to have a low rate of complications. During the last 10 years, there has been a rapid expansion in the use of sialendoscopy to diagnose and manage salivary glandular disorders in children.7 In patients with juvenile recurrent parotitis, the purpose of sialendoscopy is to diagnose and confirm the white aspect and global narrow duct. In our experience, there is always a narrow duct in comparison with adults and with children of equivalent age.7 There appears to be a difference between the excretion and secretion capacity of the parotid gland as salivary capacity increases during childhood. Stenosis in juvenile recurrent parotitis often has to be classified as S3/S4 on the LSD classification. In such cases, the aim of sialendoscopic treatment is to enlarge the main duct, with forced progression of 1.1 mm or if possible 1.3 mm, using an all-in-one sialendoscope in the Stensen duct. Sialendoscopy is also used in the same session to provide strong and complete irrigation and dilation of the Stensen duct.

Diagnostic Work-Up

For the parotid gland, all patients should have a diagnostic sialendoscopy and possibly imaging work-up including computed tomography (CT) of the salivary glands, sialo-magnetic resonance imaging (sialo-MRI), or sialography. CT is currently the best method of diagnosing salivary stones. If the CT scan does not confirm the diagnosis of a stone, further investigation using sialography or sialoMRI may be helpful for diagnosing ductal stenosis before proceeding to interventional sialendoscopy.8

For the LSD classification, two additional criteria are required before interventional sialendoscopy is considered in patients with stones:

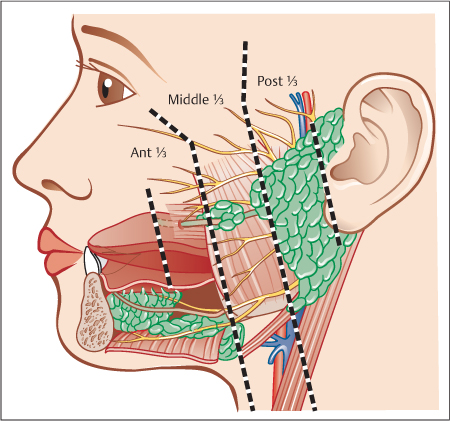

Firstly, it is important to localize the stone’s position within the duct anatomically: in the distal third of the Stensen duct (in front of the anterior border of the masseter muscle), the middle third (between the anterior border of the masseter muscle and the substance of the gland), or the proximal third of the duct (within the gland substance itself) (Fig. 15.3).

Firstly, it is important to localize the stone’s position within the duct anatomically: in the distal third of the Stensen duct (in front of the anterior border of the masseter muscle), the middle third (between the anterior border of the masseter muscle and the substance of the gland), or the proximal third of the duct (within the gland substance itself) (Fig. 15.3).

Fig. 15.3 Lateral view of the three parts of the Stensen duct. Distal (anterior) third: between the papilla and the anterior border of the masseter muscle. Middle third: between the anterior border of the masseter muscle and the parotid gland. Proximal (posterior) third or intraglandular portion: inside the gland itself.

In the submandibular gland, CT is the best imaging technique, and three criteria are used for the LSD classification:

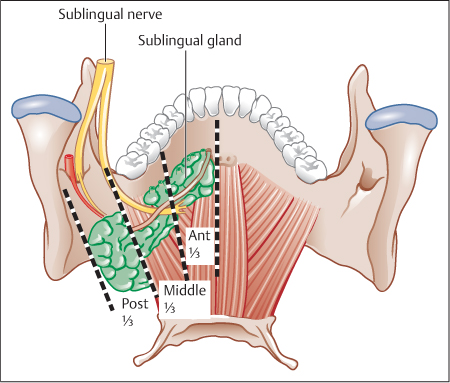

Firstly, the location of the stone: in the anterior third (from the papilla to the lingual nerve crossing, in front of the first lower molar), in the middle third (from the lingual nerve crossing to the gland), or in the posterior third (in the gland) (Fig. 15.4).

Firstly, the location of the stone: in the anterior third (from the papilla to the lingual nerve crossing, in front of the first lower molar), in the middle third (from the lingual nerve crossing to the gland), or in the posterior third (in the gland) (Fig. 15.4).

Secondly, the stone’ s diameter: in contrast to the parotid gland, stones smaller than 3 mm in diameter are often mobile and stones over 4 mm are more often impacted.

Secondly, the stone’ s diameter: in contrast to the parotid gland, stones smaller than 3 mm in diameter are often mobile and stones over 4 mm are more often impacted.

The third and most important criterion is whether the stone is bimanually palpable. This is because palpable submandibular stones can always be removed via the intraoral approach.9,10

The third and most important criterion is whether the stone is bimanually palpable. This is because palpable submandibular stones can always be removed via the intraoral approach.9,10

Contraindications

As sialendoscopy is a conservative technique, there are very few contraindications. However, if other more aggressive procedures are scheduled in the same surgical session (laser, combined techniques), some contraindications need to be observed. Some of these are not specific and mostly relate to comorbid conditions such as hemostasis and anticoagulant treatment (aspirin, anti-vitamin K, clopidogrel) or hemostasis pathologies, or even relative contraindications for the use of local anesthesia such as patients with active pustular disease. There is also one specific contraindication: intraductal infections hinder the procedure due to loss of vision and involve an increased risk of creating false routes due to ductal fragility in these patients.

Fig. 15.4 Posterior view of the three parts of the Wharton duct. Distal (anterior) third: between the papilla and the lingual nerve crossing (lower third molar, level l). Middle third: between the lingual nerve crossing and the submandibular gland. Proximal (posterior) third or intraglandular potion: inside the gland itself.

Contraindications for interventional sialendoscopy are:

Contraindications for interventional sialendoscopy are:

Ductal infection, with pus in the duct.

Ductal infection, with pus in the duct.

Hematological pathologies or anticoagulant medication, if a combined approach with interventional sialendoscopy and open surgery is planned (relative contraindications).

Hematological pathologies or anticoagulant medication, if a combined approach with interventional sialendoscopy and open surgery is planned (relative contraindications).

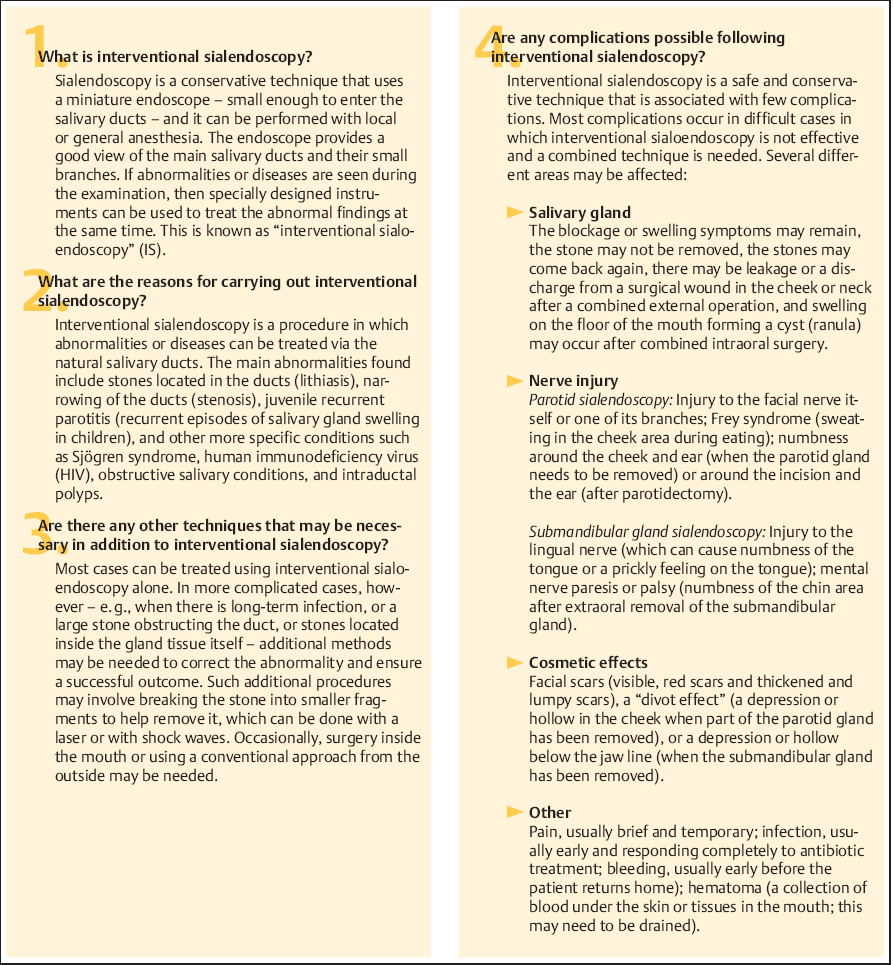

Patient Information and Consent

The patient has to receive information about the procedure to be undertaken and the risks associated with it. A single key point is that everything possible should be undertaken at a single session, even if in rare cases a submandibular gland has to be removed. A consent form must be completed in the patient’s presence and signed by the patient and the surgeon who will be carrying out the interventional sialendoscopy procedure (Fig. 15.5). In patients with parotid stones, the possibility of a combined approach being needed, with a potential risk of injury to the facial nerve, must be explained and agreed with the patient. The consent process underlines the value of an effective preoperative evaluation including ultrasonography or CT to document the number and location of stones and allow appropriate planning of the possible different procedures that may be required for a correct and appropriate surgical procedure.

Anesthesia and Positioning

Following a complete preoperative check-up, the surgeon, patient, and anesthetist will be prepared for the planned interventional sialendoscopy procedure and for the full range of optional procedures that may be necessary to achieve a successful outcome. Depending on the patient’s preferences and the duration of the procedure, there is a choice between local anesthesia (for the L1 or S1 stages in the LSD classification, a procedure taking < 30 to ≤ 60 minutes is generally required), local potentiated anesthesia (for the L2a and S2 stages, < 1 to 2 hours is required) and general anesthesia (for the L2b and L3 and S3 or S4 stages, which can only be treated with combined techniques, a procedure of 2 hours or more is indicated).

Fig. 15.5 An example of an informed consent form.

There are some specific points to be considered in relation to anesthesia in interventional sialendoscopy. The patient is placed in the decubitus (supine) position, with the head up. The choice of anesthetic agent is based on maintaining salivation (avoiding atropine-type drugs). If general anesthesia is necessary, nasotracheal intubation is preferable to ensure that there is still adequate space in the mouth for any intraoral procedures that may be needed.

The optimal choice of anesthesia depends on the planned intervention time:

The optimal choice of anesthesia depends on the planned intervention time:

30–60 minutes: local anesthesia is recommended (a motivated and cooperative patient is mandatory).

30–60 minutes: local anesthesia is recommended (a motivated and cooperative patient is mandatory).

30–120 minutes: local potentiated anesthesia (a motivated and cooperative patient is recommended).

30–120 minutes: local potentiated anesthesia (a motivated and cooperative patient is recommended).

30–180 minutes: general anesthesia with nasotracheal intubation (also for uncooperative patients).

30–180 minutes: general anesthesia with nasotracheal intubation (also for uncooperative patients).

Equipment

Therapeutic Sialendoscopes

Therapeutic Sialendoscopes

All of the sialendoscopes that are used for diagnostic sialendoscopy can also be used for interventional sialendoscopy (see Chapter 9). In interventional sialendoscopy, it is necessary to have an additional working channel to insert and work with instruments inside the salivary ductal system. The working channel may be incorporated into the sialendoscope itself, as in all-in-one sialendoscopes, or may be a dedicated cannula, with the sialendoscope being inserted into a second cannula. Three different diameters of all-inone (Storz) sialendoscopes are available—1.1 mm, 1.3 mm, and 1.6 mm. The surgeon has to anticipate the ductal size and then select the endoscope to start with (2 mm for the parotid and 3 mm for the submandibular gland) and the type of instrument that will need to be inserted to work within the ductal system (e.g., Dormia baskets, guide wire, balloon, laser fibers). In most cases, the 1.3-mm endoscope fits, except when a balloon or grasping forceps are needed, as a larger working channel is then necessary (new balloons suitable for a 0.6-mm or even 0.5-mm working channel have recently been designed, so that it may be possible in the future to use balloons with smaller endoscopes as well).

Cannulas (Double-Flow with Working Channel)

Cannulas (Double-Flow with Working Channel)

There is a choice between all-in-one sialendoscopes with a working channel and diagnostic sialendoscopes that are inserted into one of the channels of a double-cannula scope, with the other channel being used for the interventional instruments. Different sizes of double-channel cannula are available (0.65 + 0.9 mm, 0.65 + 1.15 mm, 0.9 + 1.15 mm, 1.15 + 1.15 mm), and the choice is based on the estimated duct diameter and the range of instruments to be used (Fig. 15.6).

A surgeon purchasing his or her first equipment for interventional sialendoscopy should test the different systems available, in order to decide whether the easier handling of all-inone endoscopes is more important or the additional freedom provided by combining simple endoscopes with cannula systems.

A surgeon purchasing his or her first equipment for interventional sialendoscopy should test the different systems available, in order to decide whether the easier handling of all-inone endoscopes is more important or the additional freedom provided by combining simple endoscopes with cannula systems.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses

Secondly, it is important to estimate the stone’s diameter (larger or smaller than the duct itself; the Stensen duct is usually less than 3 mm). Thus, if a stone is less than 2 mm in diameter, it is likely to be mobile, whereas a stone larger than 3 mm is more likely to be stuck in the duct, making endoscopic removal more difficult.

Secondly, it is important to estimate the stone’s diameter (larger or smaller than the duct itself; the Stensen duct is usually less than 3 mm). Thus, if a stone is less than 2 mm in diameter, it is likely to be mobile, whereas a stone larger than 3 mm is more likely to be stuck in the duct, making endoscopic removal more difficult.