Esthetic anterior implant restorations: Surgical techniques for optimal results

![]() Additional illustrations can be found on the companion website at www.blockdentalimplantsurgery.com

Additional illustrations can be found on the companion website at www.blockdentalimplantsurgery.com

Esthetic implant restorations represent a challenge to reproduce natural-appearing restorations with natural- and esthetic-appearing soft tissue bulk and form.1,2 An ideal implant site with complete preservation of bone and the overlying soft tissue is infrequently seen. Most esthetic-requiring implant sites have deficiencies in the ideal bone and overlying soft tissue and must be enhanced with a variety of surgical techniques. This chapter provides surgical guidelines for handling esthetic implant sites that have hard tissue compromise. The chapter discusses the reconstruction of soft tissue deficiencies for esthetic implant restorations.

Critical factors for esthetic central incisor implant restorations

The central incisor is the dominant tooth in the smile (Figure 9-1). Gingival problems, such as recession of the facial gingival margin, clefts, scars from vertical incisions, lack of papilla, discontinuous bands of keratinized gingiva (KG), and changes in gingival thickness all have a major effect on the final esthetic restoration. These problems must be prevented or compensated for to provide the patient with an esthetic tooth rather than simply a crown on an implant.

Six related areas must be evaluated preoperatively for implant restoration of the single central incisor, as follows (Figure 9-2):

1. Bone. Assessment requires very accurate determination of bone width and height, at the crest, midcrestal, and apical regions, as well as ridge and root prominence contour.

2. Soft tissue. Assessment includes the pre-extraction levels of the gingival margin, the quality and thickness of the gingiva, and the presence or absence of papilla.

3. Smile line. The level and contour of the smile may mask gingival problems, as well as highlight small discrepancies.

4. Color of the teeth. Some teeth are perfectly white and homogenous, but others are yellow with staining patterns.

5. Symmetry. The presence of symmetric anterior dentition can have a beautifying effect on the esthetic outcome, and lack of symmetry brings nonesthetic attention to the restoration.

6. Position of the implant. If the implant is too far labial, an esthetic outcome is not possible. Accurate placement of the implant, avoiding excessive cervical contouring of the crown, is critical to achieve an esthetic restoration. The implant must be placed vertically to allow for optimal emergence of the crown with bone-level maintenance at the level of the implant, with minimal bone-level changes over time.

Bone and soft tissue

A periapical radiograph can be used to assess the crestal level of bone on the adjacent teeth. If the bone is at the level or within 1 mm of the cementoenamel junction (CEJ) of the adjacent teeth, papilla support is expected. Ryser et al.3 found that the most critical factor for predicting papilla in the final restoration was the distance of bone from the contact point of the teeth to the level of bone on the adjacent teeth. Thus, a periapical radiograph combined with the observation of adequate papilla before tooth extraction is often the basis for predicting the esthetic quality of the final restoration (Figures 9-3 to 9-8).

Loss of bone occurs most often on the labial surface (see Figures 9-5 and 9-6). If labial bone loss is limited to 3 mm from the planned gingival margin, the implant can be placed at the level of the remaining bone with minimal esthetic compromise as long as the original position before tooth extraction of the facial gingival margin is appropriate and the gingiva has adequate thickness. If gingival recession is present, extrusion of the tooth may be necessary to reposition the facial gingiva.

Loss of all of the labial bone

Labial orientation of the implant results in gingival recession because of the labial position of the implant (see Figure 9-7, A and B). When a crown is placed on a labially positioned implant in the esthetic zone, excessive gingival contour results in apical migration of the gingiva. This situation often requires removal of the malposed implant to gain a final esthetic result.

Placement of implants into extraction sockets immediately after tooth extraction

The advantages for placing implants into the fresh extraction socket include:

1. Decreasing the amount of time from extraction to final restoration

2. Decreasing the morbidity of several surgical procedures

3. Increasing the efficiency for preservation of ridge contour by using the labial bone to retain and position grafts

4. Molding the soft tissue profile by the use of concave subgingival or anatomically correct healing abutments

5. In specific cases, placement of a fixed provisional restoration eliminating the use of removable provisional

Smile line (see figure 9-2)

Patients may show excessive gingiva for two reasons. One reason may be skeletal dysmorphism, with vertical maxillary excess present in the anterior maxilla. These patients’ teeth most likely are normal in length, with the central incisor approximately 10.5 to 11 mm tall. To correct vertical maxillary excess as a skeletal problem, an osteotomy is required to reposition the maxilla superiorly. The deficient lip may be short in the length of the skin above the wet line, or the bulk of the upper lip may be deficient. Lip augmentation may be an appropriate procedure rather than, or combined with, skeletal surgery.4

A second common reason for excessive gingival show on smiling is short teeth caused by passive altered eruption. These teeth are normal in length structurally, but they are covered with gingiva along their cervical region because of passive eruption. Treatment of this problem, which is dental in origin, is crown lengthening.5 For these patients, implant crown planning may include crown lengthening. The final gingival margin needs to be determined before implant placement to know exactly where to place the implant vertically, which should be 3 mm apical to the planned facial gingival margin. The workup should include photographs with computer-generated adjustment of the teeth and gingiva to find the optimal gingival show. At the time of crown lengthening, a surgical stent is made available to reposition the gingiva accurately within 0.5 mm.

Color of adjacent teeth

In older patients with staining on their teeth, a new implant crown will be more acceptable if the staining and other discoloration or tooth length are incorporated into the implant crown to keep the anterior teeth natural in appearance. The patient in Figure 7-9, O has the final restoration whiter than his adjacent teeth because he plans on whitening the remaining teeth. The presence of a diastema may be acceptable in the patient. If gingival recession is present on adjacent teeth, creative ceramics, including dentin and pink porcelain, may be appropriate. Thus, for each patient, consideration should be given to matching the other teeth.

Prognostic factors

Loss of labial bone

When a tooth is removed, a labial bone defect may exist. The ideal graft result is a ridge that has a convex profile that simulates an underlying tooth root, such as the root prominence. As a labial bone defect increases in dimension and shape, the final bone graft bulk may result in a flat, rather than a convex, root prominence. Therefore, soft tissue augmentation or further hard tissue augmentation with a nonresorbable material may be needed. If the ridge crest is exposed and found to be flat but sufficient for implant placement, the establishment of a root prominence is essential because of the smile line. In this situation, sintered xenograft can be placed over the ridge to “plump” the ridge form, establishing a root prominence (see Figure 9-8).

When the single-tooth edentulous site in the central incisor region is examined, four surfaces of bone need to be evaluated. The mesial and distal interproximal crestal bone surfaces on the adjacent teeth determine the bone support for the papilla. The interproximal bone level on the adjacent tooth is the most critical bone determinant of papilla support3 (Figure 9-9).

Bone can be restored to the width of the bone at the mesial or distal surfaces facing the adjacent teeth. It is difficult to establish long-term maintenance of the convex ridge profile after this bone has been lost. In the thick gingival biotype, this is less of a problem (Figure 9-10). In the thin biotype, however, it is a significant problem. The lip line must be assessed. Often the problem can be solved by using carefully designed crown contours. The use of temporary prostheses is critical in these patients to develop optimal gingival architecture.

Diagnosis, treatment planning, and surgical techniques

To establish the treatment plan, the surgeon and restorative dentist initiate a diagnostic phase at the patient’s first visit. Articulated models are used to create an esthetic diagnostic tooth setup using wax or denture teeth to determine the extent of missing hard and soft tissues. The planned restoration is used to determine the need for hard and soft tissue grafting.6–12 The use of virtual tooth setups can be used to simulate tooth positions, eliminating the need for study models and wax setups. The virtual plan can be milled into a mask and tried in the patient’s mouth. In the future, the use of digital methods rather than laboratory models will dominate the market.

In a series of 100 consecutive cases of single anterior maxillary implants treated with a traditional two-stage technique, fewer than 20% of patients had adequate bone and soft tissue with no need for hard or soft tissue grafts. Another 20% of the single anterior maxillary implant sites appeared to have adequate bone, but soft tissue thickness was deficient, requiring only an adjunctive soft tissue procedure after implant placement. The most common finding for esthetic implant sites was inadequate bone and soft tissue, requiring both bone and soft tissue augmentation.13

Patients have either a tooth in need of extraction or an edentulous space from a prior extraction. When extracting a tooth with plans for its replacement with an implant, the clinician must decide whether to perform an immediate implant placement or a delayed placement.10,14–18 Implants are not placed at the time of extraction when signs of infection are present. These signs include severe pain, the presence of granulation tissue, hyperplastic and hyperemic gingiva, periapical radiolucency, serous or purulent exudate, and lack of adequate bone for the restoration. If an infection occurs after placement of an implant in the esthetic zone, severe gingival compromise results, and an ideal esthetic restoration is difficult to achieve. Therefore, delaying implant placement for a short period time to allow for resolution of the infection after tooth extraction is the safest method for esthetic implant restoration. However, delaying implantation may result in loss of labial bone. Careful clinical judgment needs to be used in these cases.

When extracting a tooth in the anterior maxilla, incisions are made within the sulcus but without vertical release. The tooth is minimally subluxed and removed with preservation of the labial bone if present. Gentle curettage is performed to remove granulation tissue from the socket. The walls of the extraction site are gently probed to determine the amount of bone available when the implant is placed. The natural healing response of the extraction site forms woven bone within 8 weeks. If labial bone is missing, grafting within the socket is performed with mineralized bone allograft, with an onlay of sintered xenograft (bovine or equine) to prevent excessive hard tissue grafting 3 to 4 months later (Figure 9-11). Techniques used to replace the missing tooth temporarily include a removable partial prosthesis, bonding a temporary pontic to the adjacent teeth, or the use of a type of Essix device.

Most anterior maxillary single-tooth sites have inadequate bone and soft tissue, requiring both bone and soft tissue augmentation. The height of the papilla reflects the underlying crestal bone height on the adjacent teeth.11,19 Careful assessment of the bone levels on the adjacent teeth enables the surgeon and restorative dentist to inform patients of the realistic expectations of retaining or creating papilla for an esthetic single-tooth restoration. For example, when the level of crestal bone on a central incisor is apical to the CEJ of the incisor and the distance from the crestal bone to the proposed contact of the lateral incisor single-tooth implant restoration is greater than 7 mm, the chances of achieving adequate papilla are low.19–21 Patients are counseled before surgery concerning the realistic expectations of the papillary prognosis based on the adjacent bone–tooth height relationship. For patients with 7 mm or greater distance from the contact area to the crestal bone, papilla-sparing incisions are used rather than sulcular incisions and an enveloped reflection.

Incision design

The following guidelines to proper implant placement can prevent problems:

1. The implant should be placed 3 mm countersunk from the planned gingival margin of the restoration. Implants with polished collars or nonmedialized abutment implant interfaces should be avoided in the esthetic zone because of expected 1 to 2 mm of crestal bone loss, which can result in gingival recession on the facial aspect.

2. The angulation of the implant should place it slightly palatal to the incisive edge of the restoration.

3. The labial edge of the implant should be at least 2 mm palatal to the planned labial edge of the gingival margin portion of the restoration.

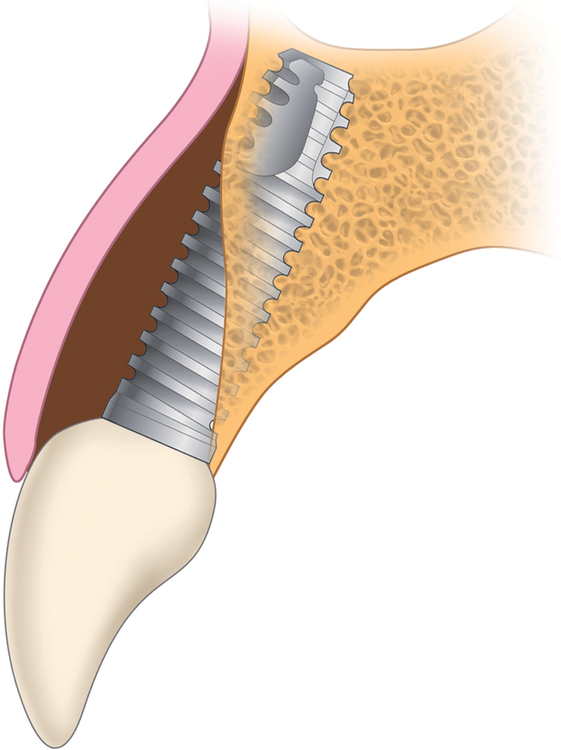

Bone may be lacking at the apical third, middle third, or coronal third of the implant body, or there may be combinations of fenestrations or dehiscences. These areas require hard tissue grafts to prevent epithelial ingrowth and potential soft tissue problems. In addition, thin bone covering the implant is most likely insufficient to restore horizontal bone contours, mimicking root prominence; therefore, thin bone also needs to be grafted to achieve the desired esthetic result.22–24

Decisions affecting treatment

The decision tree in Figure 9-12 outlines the major choices the surgeon and restorative dentist face when placing anterior maxillary implants, as well as implants for other sites in the jaws.

The first decision concerns the adequacy of alveolar bone. Is the alveolar bone width satisfactory? Is the alveolar bone height satisfactory? The preoperative physical examination and the diagnostic setup, with appropriate radiographic studies (e.g., panoramic and periapical views and tomograms), should provide the surgeon with an accurate understanding of the anatomy of the surgical site as follows (Figure 9-13):

1. If both the alveolar bone width and the alveolar bone height are satisfactory, the implant can be placed without hard tissue grafting.

2. If a vertical bone defect is present with adequate alveolar bone width, an onlay bone graft or other bone-regenerative process is indicated before placement of the implant.

3. For thin bone, which is slightly less than or greater than the diameter of the implant, the implant can be placed and the area grafted simultaneously as long as the vertical height of bone is adequate. Grafting the labial surface helps form a root eminence, which enhances the natural appearance of the final restoration.

4. If the vertical alveolar bone height is deficient along with a thin ridge, an onlay graft or other regenerative procedure is indicated before the implant is placed.

5. If the bone is severely thin, preventing implant stability at placement, with or without a vertical defect, an onlay graft or other bone-regenerative procedure is indicated before the implant is placed.

Thin bone width and sufficient bone height

Ridge shapes can lead to thin bone in the apical, middle, or coronal third of the implant site or any combination of these three areas. Thus, the implant surgeon must be aware of these potentially thin areas, which require grafting to obturate the defect and reduce the possibility of soft tissue invagination along a portion of the implant (Figures 9-14 to 9-16).

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses