Occlusion

• To understand how the eruption schedule, growth, and ultimate alignment of the teeth are related

• To understand how muscle forces affect the alignment of the teeth

• To define curve of Spee, curve of Wilson, sphere of Monson

• To understand the maxillary to mandibular vertical alignment of teeth

• To define overjet, overbite, crossbite, and open bite and to understand how they occur

• To identify the three occlusal classifications

• To understand the relationship that exists between the teeth during lateral excursive movements

POSITION AND SEQUENCE OF ERUPTION

The development of occlusion begins with the eruption of the primary teeth (see Fig. 5-7, A). Usually the first teeth to erupt are the central incisors with the mandibular teeth erupting slightly before the maxillary. The eruption of the lateral incisors, which occurs next, follows the same sequence.

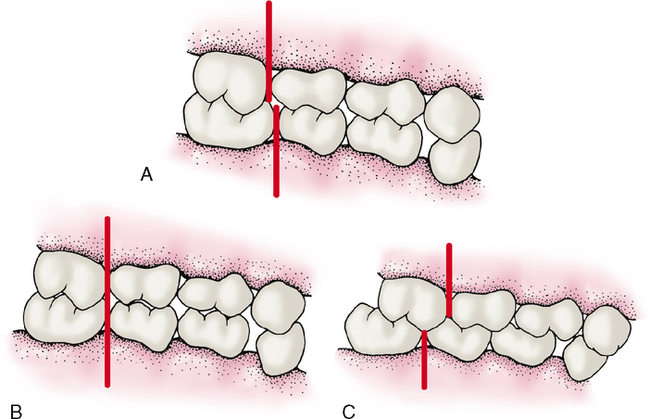

The primary dentition, which is usually complete by about 2.5 years of age, erupts in a more upright position than secondary teeth replacements. The average overjet of primary teeth is 3.0 mm, and the average overbite is 2.5 mm. The primary occlusion has one of three possible anteroposterior molar relationships called steps or planes. The majority of children has a mesial step between the distal surfaces of the second primary molars (Fig. 6-1, A). The mandibular molars are situated more mesially than their maxillary counterparts, thereby forming a mesial step. A smaller but still large group of children exhibits a flush terminal plane, with the distal surfaces of the deciduous second molars even with each other (Fig. 6-1, B). A still smaller minority has a distal step (Fig. 6-1, C). How would you describe a distal step in comparison with a mesial step or flush terminal plane? Note the large diastema or space in the mandibular arch between the canine and first molar.

As a child grows in height and weight, so too do the jaws. This growth of the mandible and maxilla results in horizontal and vertical growth of the dental arches. The teeth, however, remain the same size. Thus as the arches grow, spaces called diastemas form between the teeth. The largest spaces are often found mesial to the maxillary primary canines and distal to the mandibular canines. These spaces are called primate spaces, and although not always present, they are characteristic of all primates, including man (Fig. 6-2). As growth continues, diastemas also develop between the incisors.

DEVELOPMENT OF THE MESIAL STEP

A mesial step is further enhanced as the deciduous molars exfoliate and are replaced by the narrower permanent premolars. Extra space called leeway space is gained from this exchange of the second premolars. The earlier eruption cycle of the mandibular teeth allows them to capitalize on this exchange before the maxillary teeth, which further helps establish the mesial step (Fig. 6-3).

HORIZONTAL ALIGNMENT

If this balance of forces is disturbed, a malocclusion, or an abnormal alignment of the teeth within the dental arches, can result. Abnormal forward thrusting of the tongue against the anterior teeth can cause such an imbalanced state (Fig. 6-4). Tongue thrusting causes the maxillary anterior teeth to protrude labially out of the mouth. This is especially true if an underdeveloped upper lip is evident along with the tongue thrust.

CURVE OF SPEE, CURVE OF WILSON, AND SPHERE OF MONSON

Usually the buccal cusp tips of posterior teeth, seen in alignment from a lateral view (see Fig. 6-6), conform to a fairly even curve in an anterior to posterior direction. This curve is known as the curve of Spee.

An occlusal curve exists for posterior teeth in a direction from right to left as seen from a posterior view (Fig. 6-5). This transverse occlusal curve is called the curve of Wilson.

VERTICAL ALIGNMENT

Teeth are often thought to be vertically straight, but this is not true. The teeth are not positioned straight up and down in the mouth. The mandibular posterior teeth have a tendency to tip their crowns lingually and their roots laterally (Fig. 6-7). The maxillary posterior teeth tend to keep the crown straighter but with a slight buccal inclination and as a lingual inclination of the root (Fig. 6-8). From a lateral view, all the teeth, maxillary and mandibular, anterior and posterior, show a slight mesial inclination, with the possible exception of the maxillary third molar. Notice that the anterior teeth (Figs. 6-9 and 6-10) have a slight labial protrusion (a condition of being tipped forward), and from a frontal view, their crowns seem to incline laterally. In other words, the anterior teeth tip out to the side and toward the front (see Figs. 6-7 and 6-8).

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses