Complex Odontogenic Infections

Thomas R. Flynn

Odontogenic infections are usually mild and readily treated with the appropriate surgical procedure with or without supplemental antibiotic therapy. Infections that spread beyond teeth into the oral vestibule are usually managed by intraoral incision and drainage (I&D) procedures, as well as dental extraction, root canal therapy, or gingival curettage, as appropriate. The principles of management of routine odontogenic infections are discussed in Chapter 16. Some odontogenic infections are serious and require management by oral-maxillofacial surgeons, who have extensive training and experience in this area. Even after the advent of antibiotics and improved dental health, serious odontogenic infections still sometimes result in death. These deaths occur when the infection reaches areas distant from the alveolar process. The purpose of this chapter is to present an overview of deep fascial space infections of the head and neck originating in teeth, as well as several less common but important infections of the oral cavity.

Deep Fascial Space Infections

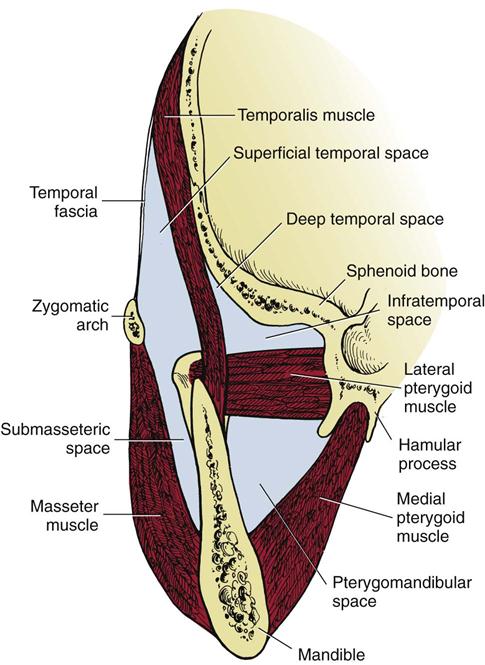

The pathways of odontogenic infection extending from the teeth through bone and into surrounding soft tissues are discussed in Chapter 16. As a general rule, infection erodes through the thinnest adjacent bone and causes infection in the adjacent tissue. Whether this becomes a vestibular or a deeper fascial space abscess is determined primarily by the relationship of the attachment of the nearby muscles to the point at which the infection perforates the bony cortical plate. Most odontogenic infections penetrate the facial cortical plate of bone to become vestibular abscesses. On occasion, infections erode into other deep fascial spaces directly (Fig. 17-1). Fascial spaces are fascia-lined tissue compartments filled with loose, areolar connective tissue that can become inflamed when invaded by microorganisms. The resulting process of inflammation passes through stages that are seen clinically as edema (inoculation), cellulitis, and abscess. In healthy persons, the deep fascial spaces are only potential spaces that do not exist. The loose areolar tissue within these spaces serves to cushion the muscles, vessels, nerves, glands, and other structures that it surrounds and to allow relative movement between these structures. During an infection, this cushioning and lubricating tissue has the potential to become greatly edematous in response to the exudation of tissue fluid and then to become indurated when polymorphonuclear leukocytes, lymphocytes, and macrophages migrate from the vascular space into the infected interstitial spaces. Ultimately, liquefactive necrosis of white blood cells and this connective tissue leads to abscess formation, and spontaneous or surgical drainage typically leads to resolution. This is the pathophysiology of the stages of infection that clinicians see as edema, when bacteria inoculate the tissues of a particular anatomic space; cellulitis, when an intense inflammatory response causes all of the classic signs of inflammation and abscess, when small areas of liquefactive necrosis coalesce centrally to form pus within tissues.

On the basis of the relationship between the point at which the infection erodes through alveolar bone and surrounding muscle attachments, infections arising from any maxillary or mandibular tooth can cause vestibular, buccal, or subcutaneous space infections. Infections passing beyond the alveolar process on the deep (toward the oral cavity) side of the nearby muscle of facial expression invade the vestibular space, and those that enter soft tissue on the superficial (toward skin) side of those muscles enter the buccal or the subcutaneous space. Infections arising from maxillary teeth also tend to spread into the infraorbital, palatal, orbital, and infratemporal spaces, and the maxillary sinus (Box 17-1). Mandibular dental infections also tend to spread into the submandibular, sublingual, submental, and masticator spaces. Infections can extend beyond these primary spaces into the deeper fascial spaces of the neck, such as the lateral pharyngeal, retropharyngeal, carotid, and pretracheal spaces. From there, such infections can spread into the danger space and the mediastinum. In addition, infections can rise superiorly through the sinuses or vascular structures to invade the brain or the intracranial dural sinuses such as the cavernous sinus.

Infections of the deep fascial spaces can be classified as having low, moderate, or high severity, according to their likelihood of threatening the airway or other vital structures. Low-severity infections are not likely to threaten the airway or vital structures. Moderate-severity infections hinder access to the airway by causing trismus or elevation of the tongue, which can make endotracheal intubation difficult. High-severity infections can directly compress or deviate the airway or damage vital organs such as the brain, heart, lungs, or skin (as in necrotizing fasciitis, popularly known as flesh-eating bacterial infection.) Determining the exact anatomic location of infection is a key step in determining its severity. A classification of the deep fascial spaces according to their severity is listed in Box 17-2. Examples of low-, moderate-, and high-severity infections are shown in Figures 17-2 to 17-4. Table 17-1 lists the anatomic borders of the more commonly infected deep fascial spaces of the head and neck.

Table 17-1

Borders of the Deep Fascial Spaces of the Head and Neck

< ?comst?>

| Space | Anterior | Posterior | Superior | Inferior | Superficial or Medial* | Deep or Lateral† |

| Buccal | Corner of mouth | Masseter muscle Pterygomandibular space |

Maxilla Infraorbital space |

Mandible | Subcutaneous tissue and skin | Buccinator muscle |

| Infraorbital | Nasal cartilages | Buccal space | Quadratus labii superioris muscle | Oral mucosa | Quadratus labii superioris muscle | Levator anguli oris muscle Maxilla |

| Submandibular | Anterior belly digastric muscle | Posterior belly digastric muscle Stylohyoid muscle Stylopharyngeus muscle |

Inferior and medial surfaces of mandible | Digastric tendon | Platysma muscle Investing fascia |

Mylohyoid muscle Hyoglossus muscle Superior constrictor muscles |

| Submental | Inferior border of mandible | Hyoid bone | Mylohyoid muscle | Investing fascia | Investing fascia | Anterior bellies of digastric muscles† |

| Sublingual | Lingual surface of mandible | Submandibular space | Oral mucosa | Mylohyoid muscle | Muscles of tongue* | Lingual surface of mandible† |

| Pterygomandibular | Buccal space | Parotid gland | Lateral pterygoid muscle | Inferior border of mandible | Medial pterygoid muscle* | Ascending ramus of mandible† |

| Submasseteric | Buccal space | Parotid gland | Zygomatic arch | Inferior border of mandible | Ascending ramus of mandible* | Masseter muscle† |

| Lateral pharyngeal | Superior and middle pharyngeal constrictor muscles | Carotid sheath and scalene fascia | Skull base | Hyoid bone | Pharyngeal constrictors and retropharyngeal space* | Medial pterygoid muscle† |

| Retropharyngeal | Superior and middle pharyngeal constrictor muscles | Alar fascia | Skull base | Fusion of alar and prevertebral fasciae at C6-T4 | Carotid sheath and lateral pharyngeal space† | |

| Pretracheal | Sternothyroid-thyrohyoid fascia | Retropharyngeal space | Thyroid cartilage | Superior mediastinum | Sternothyroid-thyrohyoid fascia | Visceral fascia over trachea and thyroid gland |

< ?comen?>< ?comst1?>

< ?comst1?>

< ?comen1?>

< ?comst1?>< ?comen1?>*< ?comst1?>< ?comen1?>Medial border.

< ?comst1?>< ?comen1?>†< ?comst1?>< ?comen1?>Lateral border.

From Flynn TR: Anatomy of oral and maxillofacial infections. In Topazian RG, Goldberg MH, Hupp JR, editors: Oral and maxillofacial infections, ed 4, Philadelphia, PA, 2002, WB Saunders.

Infections Arising from Any Tooth

As discussed in Chapter 16 and previously in this chapter, maxillary or mandibular teeth can cause infections of the buccal, vestibular, or subcutaneous spaces. The buccal space is actually a portion of the subcutaneous space, which extends from head to toe. Thus, a longstanding buccal space abscess tends to drain spontaneously through skin at its inferior extent near the inferior border of the mandible. Table 17-2 lists the likely causative teeth, contents, neighboring spaces into which infection may spread, and surgical approaches for drainage of the more commonly infected deep fascial spaces of the head and neck.

Table 17-2

Relations of the Deep Fascial Spaces of the Head and Neck

< ?comst?>

| Space | Likely Causes | Contents | Neighboring Spaces | Approach for Incision and Drainage |

| Buccal | Upper premolars Upper molars |

Parotid duct Anterior facial artery and vein |

Infraorbital Pterygomandibular |

Intraoral (small) Extraoral (large) |

| Lower premolars | Transverse facial artery and vein Buccal fat pad |

Infratemporal | ||

| Infraorbital | Upper canine | Angular artery and vein Infraorbital nerve |

Buccal | Intraoral |

| Submandibular | Lower molars | Submandibular gland Facial artery and vein Lymph nodes |

Sublingual Submental Lateral pharyngeal Buccal |

Extraoral |

| Submental | Lower anterior teeth Fracture of symphysis |

Anterior jugular vein Lymph nodes |

Submandibular (on either side) | Extraoral |

| Sublingual | Lower premolars Lower molars Direct trauma |

Sublingual glands Wharton’s ducts |

Submandibular Lateral Pharyngeal |

Intraoral Intraoral-extraoral |

| Lingual nerve Sublingual artery and vein |

Visceral (trachea and esophagus) | |||

| Pterygomandibular | Lower third molars Fracture of angle of mandible |

Mandibular division of trigeminal nerve | Buccal | Intraoral |

| Inferior alveolar artery and vein | Lateral pharyngeal Submasseteric Deep temporal Parotid Peritonsillar |

Intraoral-extraoral | ||

| Submasseteric | Lower third molars Fracture of angle of mandible |

Masseteric artery and vein | Buccal | Intraoral |

| Pterygomandibular Superficial temporal Parotid |

Intraoral-extraoral | |||

| Infratemporal and deep temporal | Upper molars | Pterygoid plexus Interior maxillary artery and vein Mandibular division of trigeminal nerve Skull base foramina |

Buccal Superficial temporal Inferior petrosal sinus |

Intraoral Extraoral Intraoral-extraoral |

| Superficial temporal | Upper molars Lower molars |

Temporal fat pad Temporal branch of facial nerve |

Buccal Deep temporal |

Intraoral Extraoral Intraoral-extraoral |

| Lateral pharyngeal | Lower third molars Tonsils Infection in neighboring spaces |

Carotid artery Internal jugular vein Vagus nerve Cervical sympathetic chain |

Pterygomandibular Submandibular Sublingual Peritonsillar Retropharyngeal |

Intraoral Intraoral-extraoral |

< ?comen?>< ?comst1?>

< ?comst1?>

< ?comen1?>

From Flynn TR: Anatomy of oral and maxillofacial infections. In Topazian RG, Goldberg MH, Hupp JR, editors: Oral and maxillofacial infections, ed 4, Philadelphia, PA, 2002, WB Saunders. With permission.

Infections Arising from Maxillary Teeth

Because the apices of upper lateral incisors and the palatal roots of upper premolars and molars are closest to the palatal cortical plate, infection arising from these teeth can erode through bone without perforating the periosteum. The potential subperiosteal space in the palate is the palatal space.

The infraorbital space is a thin potential space between the levator anguli oris and the levator labii superioris muscles. The infraorbital space becomes involved primarily as the result of infections from the maxillary canine tooth or by extension of infections from the buccal space. The canine root is often sufficiently long to allow erosion to occur through the alveolar bone that is superior to the origin of the levator anguli oris and below the origin of the levator labii superioris muscle. When this space is infected, swelling of the anterior face obliterates the nasolabial fold (Fig. 17-5). Spontaneous drainage of infections of this space commonly occurs near the medial or the lateral canthus of the eye because the path of least resistance is to either side of the levator labii superioris muscle, which attaches along the center of the inferior orbital rim.

The buccal space is bounded by the overlying skin of the face on the lateral aspect and the buccinator muscle on the medial aspect (Fig. 17-6). This space may become infected from extensions of infection from maxillary teeth through the bone superior to the attachment of the buccinator on the alveolar process of the maxilla. Posterior maxillary teeth, most commonly molars, cause most buccal space infections.

Involvement of the buccal space usually results in swelling below the zygomatic arch and above the inferior border of the mandible. Infections may follow the extensions of the buccal fat pad into the superficial temporal space, the infratemporal space, the infraorbital space, and the periorbital space, as illustrated in Figure 17-7. Because the fascial layers that pass over the zygomatic arch are tightly bound down to bone, swelling above and below the zygomatic arch can cause the relatively dimpled appearance over the left zygomatic arch, as seen in Figure 17-7. The zygomatic arch and the inferior border of the mandible remain palpable in buccal space infections.

The infratemporal space lies posterior to the maxilla. The space is bounded medially by the lateral pterygoid plate of the sphenoid bone and superiorly by the base of the skull. Laterally and superiorly, the infratemporal space is continuous with the deep temporal space (Fig. 17-8). Essentially, the infratemporal space is the bottom portion of the deep temporal space. The space contains branches of the internal maxillary artery and the pterygoid venous plexus. Importantly, emissary veins from the pterygoid plexus pass through foramina in the base of the skull to connect with the intracranial dural sinuses. Because the veins of the face and the orbit do not have valves, bloodborne infections may pass superiorly or inferiorly along their course. The infratemporal space is the origin of the posterior route by which infections may spread into the cavernous sinus (Fig. 17-9). The infratemporal space is rarely infected, but when it is, the cause is usually an infection of the maxillary third molar.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses