14

Pain and Anxiety Control

- local anaesthetics in pain control

- local anaesthetic techniques in dentistry

- anxiety control techniques

- patient monitoring techniques

- the role of the dental nurse during the use of anxiety control techniques

When a patient has dental disease, especially dental caries, the dental team will aim to treat and eradicate that disease by performing some type of dental or soft tissue surgery on the patient.

- Restorative treatment performed directly on the tooth involved by:

- fillings

- endodontics

- fixed restorations (crown, veneer, inlay).

- Extraction of the tooth:

- simple extraction

- surgical extraction.

- Periodontal treatment involving the supporting structures of the tooth:

- scaling and debridement

- periodontal surgery.

- Other types of soft tissue surgery.

All these dental techniques are covered in later chapters.

As described in Chapters 9 and 10, the oral cavity has an excellent nerve supply to all areas and anyone who has suffered the misery of ‘toothache’ or even minor mouth ulcers will vouch for just how well developed pain reception in this area can be. To carry out any oral or dental surgical treatments without some form of pain control would be acutely painful for the patient, and the majority of procedures are therefore usually carried out under a technique of local anaesthesia.

Local anaesthesia

The term ‘anaesthesia’ is defined as ‘the loss of all sensation’ but in dentistry when local anaesthetics are administered, they produce the loss of pain sensation only – pressure can still be felt by the patient. Drugs used to produce the loss of pain sensation only would therefore be more correctly termed ‘local analgesics’.

Teeth and their support structures are particularly well innervated with a sensory nerve supply that responds to temperature, pressure and pain. Local anaesthetics must be given by injection before dental treatment begins, so that the patient is comfortable and pain free throughout the procedure. As described in Chapter 5, all sensations felt by the body tissues are transmitted as electrical impulses along the length of the sensory neurones (nerve cells) to the brain, where the information is analysed and interpreted. Local anaesthetics act by blocking these electrical transmissions from the source of the stimulation (the tooth or its surroundings), so that the information that a painful procedure is being carried out does not reach the brain. The patient is conscious and fully aware of the treatment being carried out (unless they are sedated), but they feel no unpleasant or painful stimuli.

In addition, the sensations of hot and cold are also blocked as they would be interpreted as pain under these circumstances – the heat generated when a tooth is drilled with no cooling water spray is interpreted as pain by the brain, and similarly anyone with sensitive teeth will relate to the very uncomfortable sensation that occurs when cold drinks are taken.

The sensations of pressure and vibration will remain, so for example the patient will be aware of the pushing and wiggling sensations that occur during a tooth extraction procedure, but it should be completely painless if the local anaesthetic has been administered correctly.

Local anaesthetic drugs

Many local anaesthetics are now available for use in dentistry, and they are all supplied within glass or plastic cartridges for use in special dental syringes (Figure 14.1). The cartridges are available as either 2.2 mL or 1.8 mL sizes, and contain the following.

- Anaesthetic – to block the electrical nerve transmissions to the brain so that neither pain nor temperature changes can be felt.

- Sterile water – acts as a carrying solution for the other constituents, and makes up the bulk of the cartridge contents.

- Buffering agents – maintains the contents of the cartridge at a neutral pH, so they are neither acidic nor alkaline and do not irritate the soft tissues when they are injected.

- Preservative – to give an adequate shelf-life to the contents.

- Vasoconstrictor – present in some types of local anaesthetic (but not all), and acts to prolong the action of the anaesthetic by closing (constricting) local blood vessels so that the solution is not carried away so quickly in the bloodstream.

Both the anaesthetic agent and any vasoconstrictor present are classed as drugs, and are therefore subject to strict regulations with regard to their safe disposal. The topic of waste disposal is discussed in detail in Chapter 4, and used local anaesthetic cartridges are now classified as ‘infectious hazardous waste’. Unused but out-of-date cartridges are classified as ‘non-hazardous waste’ as a medicine, although broken cartridges should be disposed of as sharps waste under the ‘infectious hazardous waste’ category.

Figure 14.1 Local anaesthetic cartridges.

The more common local anaesthetics currently in use in dentistry are as follows.

- Lidocaine – 2% lignocaine hydrochloride as the local anaesthetic with 1:80,000 adrenaline (epinephrine) as a vasoconstrictor (known as Lignospan and Xylocaine).

- Articaine – carticaine as the local anaesthetic with 1:100,000 adrenaline as a vasoconstrictor.

- Citanest – 3% prilocaine hydrochloride as the local anaesthetic, with 0.03 units/mL felypressin (Octapressin) as a vasoconstrictor.

- Citanest plain – 4% prilocaine hydrochloride as the local anaesthetic, with no vasoconstrictor present.

- Mepivacaine – 3% mepivacaine hydrochloride as the local anaesthetic, with no vasoconstrictor present (known as Scandonest).

Adrenaline (also called epinephrine) is the vasoconstrictor most commonly used in dental local anaesthetics, but it is a potent cardiac stimulant which increases the rate and depth of a patient’s heart beat generally. This explains its usefulness as an emergency drug in various situations, such as during anaphylaxis when the blood pressure falls to such low levels that the heart can stop beating (see Chapter 6). Unfortunately, it also means that locals containing it cannot be used safely on patients with certain medical conditions.

- Hypertension – high blood pressure.

- Cardiac disease – poor functioning of the heart, whether due to valve defects or acquired problems such as coronary artery disease.

- Hyperthyroidism – an overactive thyroid gland, which tends to increase the overall metabolic rate of the patient, including the heart rate.

In addition, care should be taken with certain groups of patients or with those taking certain drugs.

- Elderly patients – as they may have complicated medical histories, be taking other drugs that could react with adrenaline, have undiagnosed diseases, or simply may not be able to excrete drugs efficiently due to their age.

- Hormone replacement therapy (HRT) – given to women to counteract the adverse effects of the menopause and prevent the development of osteoporosis (thinning of the bones), but which may produce hypertension as a side-effect.

- Thyroxine – a drug given to patients suffering from hypothyroidism (an underactive thyroid gland), which increases their overall metabolic rate, including the heart rate.

Figure 14.2 Close-up of cartridge details.

Theoretical risks are also said to exist with patients taking certain antidepressants, including tricyclics and monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs).

The use of local anaesthetics containing no vasoconstrictor is an alternative in these groups of patients, but then the analgesic action would wear off more quickly and there is more risk of haemorrhage during surgical procedures. Alternatively, they can be given 3% Citanest – the only contraindications to its use being pregnancy, as felypressin is a potent drug used to induce labour due to its contractive action on the muscles of the uterus.

Local anaesthetic equipment

The equipment required to administer the local anaesthetic consists of the cartridge itself, the syringe and needle, and sometimes a topical anaesthetic is used.

The anaesthetic cartridge is a glass or plastic tube sealed at one end with a thin rubber diaphragm and at the other with a rubber bung (Figure 14.2). A special syringe and needle are used with dental cartridges. When a cartridge is inserted in the syringe, a double-ended needle pierces the diaphragm. Solution is injected when the syringe plunger engages the rubber bung and pushes it down the tube. As some patients are now known to have an allergy to latex, the rubber bung and diaphragm have been replaced by plastic alternatives in some types of specialised cartridges.

Various designs of local anaesthetic syringe are available, some being side-loading and some being breech-loading (from the back) (Figure 14.3). The majority are metallic so that they can be sterilised in an autoclave after each use, but single-use disposable ones are now also available.

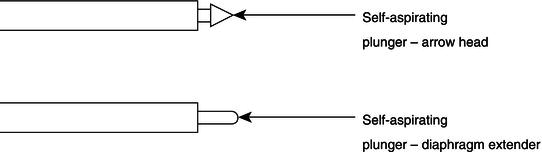

In addition, the head of the plunger is adapted in some syringes so that the dentist can use an aspirating technique when administering the local anaesthetic, for patient safety reasons (Figure 14.4). The technique is designed to avoid the injection of the solution into a blood vessel, rather than around the nerve as is the required position. Once the needle has been positioned, the plunger is drawn back or pressed slightly and released, before injection, so that if a blood vessel has been pierced, blood will flow visibly into the anaesthetic cartridge. The needle tip can then be repositioned, the cartridge aspirated to check again, and then the contents safely injected into the correct position around the nerve.

Figure 14.3 Local anaesthetic syringes.

Figure 14.4 Self-aspirating syringe plungers.

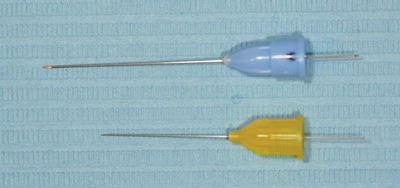

All syringes have a universal thread end for the needle to be positioned and attached. The needles are provided in various lengths and sizes, or gauges, depending on the type of injection to be given (Figure 14.5). Smaller sizes are less painful to use but are too fine to be used in some oral injection sites, especially where muscle tissue has to be penetrated to reach the target nerve.

Topical anaesthetics are used on the surface of the oral mucous membrane to provide localised anaesthesia in that area, so that a syringe needle can be inserted painlessly and the local anaesthetic can be administered. They are supplied as a paste, solution or spray which is applied to the appropriate site a few minutes before an injection is given. Commonly used surface anaesthetics are 5% lidocaine paste (Figure 14.6) or 20% benzocaine.

These products are also used to minimise the discomfort of superficial scaling, fitting matrix bands, and for preventing stimulation of the gag reflex when taking impressions.

Figure 14.5 Local anaesthetic needles.

Figure 14.6 Topical anaesthetic gel.

Local anaesthetic administration techniques

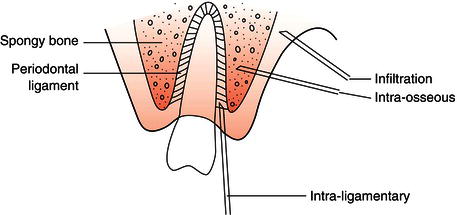

Due to the variable anatomy of the jaws, the administration technique required to anaesthetise teeth is dependent on whether the relevant sensory nerve is deep within the bone or superficial to the surface. Other techniques can be used to anaesthetise individual teeth and their surroundings only, without causing any soft tissue effects. Generally, there are four basic methods of administering a dental local anaesthetic (Figure 14.7).

- Nerve block.

- Local infiltration.

- Intraligamentary injection.

- Intraosseous injection.

Nerve block

A nerve block is an injection which anaesthetises the nerve trunk as it runs in soft tissue, either before it enters the jaw bone or after it leaves it to reach the teeth and associated parts. Pain sensations from every part supplied by the nerve are blocked at the site of injection and cannot reach the brain. A nerve block is used when it is necessary to anaesthetise several teeth in one quadrant or where a local infiltration cannot work.

Figure 14.7 Types of injection.

Figure 14.8 Inferior dental nerve block technique.

The most common example of this type of injection is the inferior dental block. For this injection, the anaesthetic solution is injected over the mandibular foramen, on the inner surface of the ramus of the mandible (Figure 14.8). At this site the inferior dental and lingual nerves are so close to each other that both nerves are anaesthetised together. Thus it has the effect of anaesthetising all the lower teeth and lingual gum on the side of the injection, together with that half of the tongue as well. Furthermore, it anaesthetises the lower lip and buccal gum of the incisors, canine and premolars as these are supplied by the mental branch of the inferior dental nerve. So once the patient confirms the numbness of the lower lip, the dentist knows that all the lower teeth on that side are numb too.

The only part unaffected by this injection is the buccal gum of the lower molars; this area of soft tissue is supplied by the long buccal nerve which is too far from the injection site to be affected. The nerve supply of the oral cavity is covered in detail in Chapter 9.

Other nerve block injections that may be administered by the dentist are as follows.

- Mental nerve block – to anaesthetise the end portion only of the inferior dental nerve, as it leaves the mandible through the mental foramen, so that only the anterior teeth and their buccal or labial soft tissues are affected (Figure 14.9).

- Posterior superior dental nerve block – to anaesthetise this nerve before it enters the maxillary antrum, so that both the upper second and third molar teeth are affected.

Figure 14.9 Mental nerve block technique.

The nerve block technique is useful in situations where an infection is present around a tooth requiring dental treatment, as it can be anaesthetised without risking the spread of the infection by placing the injection at a distance from the tooth involved.

As stated previously, the nerves tend to run as neurovascular bundles and an aspirating technique should be used during a block injection, to prevent the inadvertent placement of the cartridge contents into a blood vessel.

Local infiltration

A local infiltration injection is given over the apex of the tooth to be anaesthetised. The needle is inserted beneath the mucous membrane overlying the jaw bone. The anaesthetic soaks through pores in the bone and anaesthetises the nerves supplying the tooth and gum at the site of injection. Thus the difference between these two types of injection is that a nerve block applies the anaesthetic to the nerve trunk, whereas an infiltration applies it to the nerve endings.

A local infiltration injection can only be used where the compact bone is sufficiently thin and porous to allow the anaesthetic to penetrate into the inner spongy bone. Thus it is usually effective for all upper teeth, and for the lower incisor teeth. The compact bone overlying the mandibular premolars and molars, however, is too thick and an inferior dental block or a mental block is necessary for these, respectively. A local infiltration can always be used to anaesthetise the local gingivae only, as will be required for procedures such as extractions.

Intraligamentary injection

The intraligamentary injection technique tends to be used in conjunction with either an infiltration or a nerve block, to produce deeper anaesthesia around hypersensitive teeth. Various specialised syringes are available, which hold the smaller 1.8 mL anaesthetic cartridge within a protective plastic sheath (Figure 14.10). The force required to administer the cartridge contents is considerable, so a ratchet design of plunger is used to maintain the pressure, and the plastic sheath prevents injury if a glass cartridge shatters during use, as sometimes happens.

Figure 14.10 Ligmaject syringe.

Figure 14.11 Intraosseous system.

The anaesthetic is administered into the periodontal ligament of the tooth, and the surrounding gingivae can be seen to blanch as it takes effect. The technique is especially useful when a nerve block has failed to produce sufficient anaethesia of the tooth, but it cannot be used in the presence of gingival infection unless the tooth is being extracted. The force required for administration may also cause some postoperative soreness for the patient.

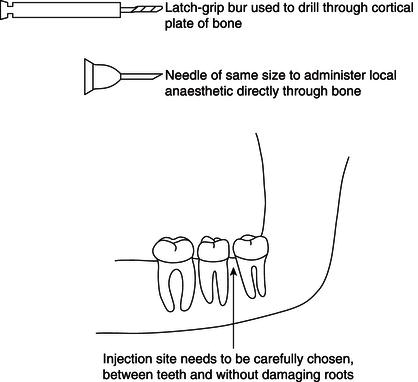

Intraosseous injection

An intraosseous injection is given directly through the outer cortical plate of the jaw and into the spongy bone between two teeth. A few drops of anaesthetic are first injected into the overlying gum to permit painless drilling of a small hole through the compact bone, to allow access for a needle to be inserted directly into the spongy bone (Figure 14.11).

This injection provides a relatively short duration, but profound depth, of anaesthesia for the tooth and buccal and lingual gum, on either side of the injection site, but it does not numb the cheek, lip or tongue. This makes it an excellent method for extractions. Other advantages are that it works immediately and rarely fails, thus making it useful where an infiltration or block has been unsuccessful. The disadvantages are that it cannot be used where gingival (gum) infection is present, nor should it be used in the region of the mental foramen of the mandible, as the nerve could easily be damaged while the access hole is being drilled.

The technique is very old but has gained a new lease of life with the introduction of the Stabident kit, containing a special drill for perforating the compact bone and a matching ultra-short needle for injecting directly into spongy bone.

Local anaesthesia for extractions

When a tooth requires extraction it is necessary to anaesthetise the surrounding periodontium as well as the tooth itself, as the periodontal ligament will be severed during the procedure. The injections required for each tooth will be more readily understood by referring back to the nerve supply of teeth.

Upper teeth

To anaesthetise any upper tooth for extraction, a local infiltration injection is given on both its buccal/labial and palatal sides. The buccal infiltration will anaesthetise the tooth and the buccal/labial periodontium, and the palatal injection will anaesthetise the palatal periodontium. It also helps to ensure sufficient anaesthesia of the tooth by infiltrating to the palatal root of the molars too.

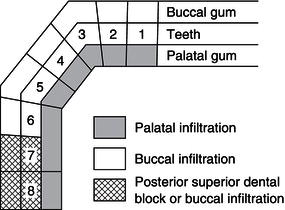

For the second and third molars, some operators prefer to give a posterior superior dental block instead of a local infiltration on the buccal side. The nerve supply of the upper teeth and their gingivae is shown diagrammatically in Figure 14.12.

Lower teeth

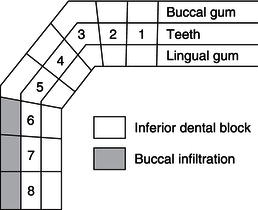

An inferior dental block injection blocks the lingual as well as the inferior dental nerve. This single injection will therefore suffice for the extraction of premolars, canine and incisors, as their buccal/labial periodontium is supplied by the end section of the inferior dental nerve, the mental nerve.

For lower molars, whose buccal periodontium is supplied by the long buccal nerve, an additional local buccal infiltration is required for full anaesthesia.

The compact bone in the incisor region of the mandible is sufficiently thin to allow the use of a labial and lingual local infiltration, and many operators prefer this technique rather than an inferior dental block for anaesthetising lower incisors. The nerve supply of the lower teeth and their gingivae is shown diagrammatically in Figure 14.13.

Local anaesthesia for restorative treatments

It is unnecessary to additionally anaesthetise the palatal or lingual gingivae as well as the tooth and buccal/labial gingivae for restorative treatments, unless the gingivae in these areas need adjustment or removal as part of the restorative procedure. Examples of when this is necessary are when:

- a cavity has been present for some time and the gingiva has grown into the space present – its removal is necessary to ensure that the filling material is fully adapted to the cavity walls

- a crown lengthening technique is required during tooth preparation for fixed prosthodontics – its adjustment is necessary to allow for a lengthened tooth preparation so that adequate retention of the restoration is achieved, or to achieve good aesthetics

- a crown has been lost and the remaining root face has been covered by gingival overgrowth – its removal is required to ensure an accurate impression is taken so that the new restoration fits the root face adequately.

Figure 14.12 Injections for upper teeth.

Figure 14.13 Injections for lower teeth.

Upper teeth

A local buccal/labial infiltration is enough for routine restorative treatments, although a posterior superior dental block is sometimes preferred for the second and third molars.

Lower teeth

An inferior dental block will anaesthetise every lower tooth, while a mental block may be used when treatment involves any tooth other than the lower molars. For restorative treatment involving just the lower incisors, a local labial infiltration will suffice instead of a full nerve block technique.

Preparation for local anaesthesia

All cartridges and needles are supplied by their manufacturers presterilised and ready for use. Reusable metal syringes are sterilised as usual in an autoclave.

A long needle of 27 gauge is used for/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses