8

Infection Control and Cleanliness

- the basic principles of infection control

- decontamination, disinfection, and sterilisation techniques

- personal protective equipment and its correct usage in the dental workplace

- cross infection and inoculation injury and their avoidance in the dental workplace

The maintenance of a high standard of cleanliness and the control of infection are topics of fundamental importance in the dental workplace, as they are in any clinical environment. All members of the dental team (including trainee dental nurses) have a duty of care to protect their patients and themselves from coming to harm while on the premises, and one potential area of vulnerability is to become contaminated by, or to acquire an infection from another patient or a member of staff, or from a dirty instrument. This is called cross-infection.

The methods used to avoid this are the foundations of good infection control, and of the principles of maintaining an adequate standard of cleanliness.

Legislation and national variation

Over the last few years, many changes and updates in the safe running of the dental workplace have occurred throughout the UK, including in the area of infection control. Unfortunately, the four countries of the UK (England, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland) have produced slightly different guidelines and are answerable to different regulators when following those guidelines. This has resulted in a complicated set of work practices in the dental environment that still must be understood and followed by dental staff, irrespective of where they work in the British Isles – and this is particularly so in the area of infection control.

For the purposes of this text, the legislation and guidelines applicable in England will be described in detail, and further information is available at www.dh.gov.uk. Students working in Northern Ireland are advised to access further specific information at www.dhsspsni.gov.uk.

Those areas of general knowledge common to all countries (definitions, basic principles, standard precautions, etc.) will form the bulk of the text.

In England, the guidelines applicable to decontamination in general dental practice (primary care dental practices) are covered by the Department of Health document Health Technical Memorandum 01-05 (HTM 01-05, Figure 8.1). Northern Ireland and Wales have their own modified versions of this document, while Scotland has not adopted it but instead has a number of organisations which provide guidance on compliance with decontamination standards. HTM 01-05 is produced as a guide on decontamination techniques for use in the dental workplace itself, and is a ‘working document’ in that it may be updated as evidence of better techniques and systems becomes available. It is intended to help dental workplaces establish a programme of continuous improvement in their decontamination techniques. Those currently included are listed in two categories.

Figure 8.1 HTM 01-05 guidance booklet.

- Essential quality requirements – the basic level of decontamination standards that all workplaces will achieve within the first year of implementation of the guidance.

- Best practice – the ‘gold standard’ to be aimed at in the future (no timescale has currently been set); the additional improvements required to achieve best practice cover the following main points.

- Use of a washer-disinfector to clean instruments

- Separate facility for decontamination tasks, away from the clinical treatment area

- Separate storage area for sterilised items, away from the clinical treatment area (a ‘clean zone’ within the decontamination room would be adequate).

Although it is accepted that many dental workplaces will be unable to achieve full ‘best practice’ status due to the limitations of their building layout, all will need to assess the improvements they can make and have a plan in place to implement what is achievable.

Throughout this chapter, the impact of HTM 01-05 on decontamination techniques will be highlighted.

Recently, registration for healthcare providers, including all dental practices in England (private, NHS or mixed practice), has been introduced and is overseen by the Care Quality Commission (CQC). Compliance with the essential quality requirements of HTM 01-05 will ensure that each dental workplace satisfies the registration requirements of the CQC in the areas of patient safety and decontamination. Initially, and in line with clinical governance requirements (see Chapter 3), the registration system will rely on self-audit and effective management within the dental workplace, although practice inspections by the CQC will occur at some point in the future.

Full registration with the CQC is provisional on each dental workplace showing that it meets essential standards of quality and patient safety in all its regulated activities, not just decontamination. This topic is discussed in more detail in Chapter 3.

The CQC acts only in England, and is not recognised in the other countries of the UK.

Need for infection control

As discussed in Chapter 7, the mouth is full of micro-organisms, some of which are harmful to the patient and to others. Consequently instruments and equipment used in dental treatment become contaminated with these micro-organisms whenever they are used, whether they are drilled into teeth, used to cut into soft tissues or are simply placed in the contaminated oral cavity. If no action were taken to clean these items after use, this micro-organism contamination would be passed on from patient to patient, from patient to dental staff, and from staff to patient. In addition, the use of dental air turbines (high-speed drills) creates an aerosol in the surgery, which falls onto the working surfaces and contaminates them too. If staff are not personally clean while taking part in chairside dental procedures, they can also contaminate patients and other staff.

The transfer of infection from person to person is called direct cross-infection, and that from person to equipment and onto a second person is called indirect cross-infection. The techniques, policies and safeguards in place to prevent the occurrence of cross-infection form the basic principles of infection control procedures.

Basic principles of infection control

A system of standard precautions (previously referred to as ‘universal precautions’) has been adopted in healthcare work, which is designed to protect staff from inoculation and contamination risks, and to protect patients from being exposed to the risk of cross-infection.

The basic principle is to assume that any patient may be infected with any micro-organism at any time, and therefore they pose an infection risk to all dental staff and to other patients. A detailed medical history questionnaire, completed at the patient’s initial attendance and updated at every appointment thereafter, will identify the majority of problems.

However, a patient may be infected with a micro-organism without showing any signs of disease, and therefore be unaware of the risk they pose to others – these are called carriers. Also, a patient may choose not to disclose their full medical history to the dental staff, and would then mistakenly be assumed to be ‘safe’ to treat.

So, if all patients are considered to be a possible source of infection and treated as such, the infection control techniques used in the dental environment will be good enough to reduce all cross-infection risks to a minimum. The other general basic principles of infection control to be adopted are summarised below.

- Apply good basic personal hygiene with regular appropriate hand washing.

- Cover existing wounds with waterproof dressings.

- Do not undertake invasive procedures if suffering from chronic skin lesions on the hands, such as eczema or dermatitis.

- Wear non-latex clinical gloves at all times when assisting in the surgery, and discard after single use.

- Avoid contamination with body fluids by wearing appropriate protective clothing, safety spectacles and masks – referred to as personal protective equipment (PPE).

- Institute approved procedures for decontamination of instruments and equipment.

- Apply good basic environmental cleaning procedures.

- Clear up blood and other body fluid spillages promptly.

- Follow the correct procedure for safe disposal of contaminated waste and sharps.

- Ensure all staff are aware of, understand and follow infection control policies and procedures.

- Ensure all staff are fully vaccinated against hepatitis B (this is now a legal requirement for all who work in the clinical environment) and that all childhood immunisations are up to date (see Chapter 7).

In the dental surgery environment itself, special methods of infection control are now routinely practised, as well as following the general points listed above. Best practice dictates that good general infection control is achieved by the following.

- Correct cleaning of the hands.

- Use of personal protective equipment.

- Correct cleaning of the clinical area.

- Correct cleaning and/or disposal of dental equipment, handpieces and instruments.

- Correct and safe disposal of hazardous waste.

Each point is discussed in detail later in this chapter.

HTM 01-05 implications – infection control policy

Under clinical governance requirements, all dental workplaces have had to have a written infection control policy in place for some time. Under HTM 01-05 guidance, the policy must now specifically cover the following points.

- Policy of action following an inoculation (sharps) injury, including occupational health contact details.

- Decontamination and storage policy for dental instruments, indicating full compliance with essential quality requirements and plans in place to achieve best practice.

- Details of procedures in use for decontamination of reusable items.

- Details of the correct management of instruments and equipment in the workplace to avoid cross-infection.

- Hazardous waste disposal policy.

- Hand hygiene policy.

- Details of required use of personal protective equipment.

- Details of recommended disinfectants and their correct use.

- Chemical spillage procedure, in line with Control of Substances Hazardous to Health (COSHH) requirements.

The infection control policy is subject to update in line with the requirements of the Health and Social Care Act 2008 – Code of Practice, or at 2-yearly intervals if shorter.

General definitions

The terms ‘cleaning’ and ‘cleanliness’ in a clinical context are quite different from a lay person’s concept of them, and the relevant terms used here are defined below.

- Social cleanliness – clean to a socially acceptable standard for personal hygiene purposes but not disinfected nor sterilised.

- Disinfection – the killing/destruction of bacteria and fungi, but not spores nor some viruses (the technique usually involves the use of special chemicals).

- Sterilisation – the process of killing all micro-organisms and spores to produce asepsis (involves the use of autoclaves, which produce high temperatures and pressure within the sterilising chamber).

- Asepsis – the absence of all living pathogenic micro-organisms.

- Decontamination – the process used to remove contamination from reusable items, so that they are safe for further use on patients and for staff to handle. This may also be referred to as ‘reprocessing’ and involves the following four stages.

- Cleaning

- Disinfection

- Inspection

- Sterilisation.

All areas of the dental workplace should be socially clean, as a minimum standard. All clinical areas of the dental workplace must be cleaned to a higher standard still, by disinfection of the contaminated work surfaces using specific cleaning agents. Equipment and instruments that are not used in the patient’s mouth but are contaminated by aerosol or splatter must also be decontaminated by disinfection. Some items may be protected by coverage with disposable plastic barrier sheets. All instruments that are used directly in the patient’s mouth and that are not single-use disposable must be sterilised before being safe to reuse on another patient.

Cleaning of the hands and general appearance

Hand washing is the most important method of preventing cross-infection, and the technique used should be that stipulated by the Health and Safety Council. Recent studies have suggested that many instances of hospital-based infection of patients with micro-organisms such as methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) are due to poor hand hygiene amongst hospital staff and visitors.

When working in the clinical area, nails should be kept short and wounds covered with a waterproof dressing to reduce the number of areas for micro-organisms to contaminate. False nails should never be worn when working at the chair side. The minimum amount of jewellery (earrings, rings, bracelets and watches) should be worn by those working in a clinical environment, for the same reason. Professionally, facial piercings and tattoos should be kept to an absolute minimum, and preferably are removed or discretely covered wherever possible.

HTM 01-05 implications – hand hygiene

Hand hygiene covers the topics of the different methods of hand washing as well as the recommended use of hand gels for disinfection purposes, as an alternative or in addition to washing, depending on the circumstances. Hand hygiene is a required topic of coverage in staff induction training, under the essential quality requirements.

Dedicated hand-washing sinks must be available in the dental workplace, and marked as such. They should have taps that can be operated either by the elbow or by foot, to avoid contamination from dirty hands.

The three levels of hand hygiene recognised are as follows.

- Social – to become physically clean from socially acquired micro-organisms, using general-purpose liquid soap.

- Hygienic – to destroy micro-organisms, maintain cleanliness and avoid direct cross-infection, using an approved antibacterial hand cleanser.

- Surgical – to significantly reduce the numbers of micro-organisms normally resident on the hands, before an invasive surgical procedure is carried out, using an approved antibacterial hand cleanser.

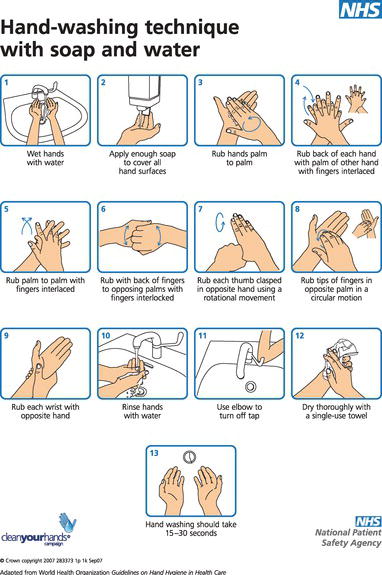

Figure 8.2 Hand wash poster. © Crown copyright. Contains public sector information licensed under the Open Government Licence v1.0.

Social hand washing provides a general level of cleanliness, and should be carried out at the start and end of each session, before preparing food or eating, and especially after using the toilet facilities. It follows a similar technique to that used for hygienic hand cleansing as described below, but should take just 10–15 sec as it need not include the wrists or forearms.

The correct procedure for hygienic hand washing should be displayed in poster form at each dedicated sink, and the instructions are as follows (Figure 8.2).

- Turn on the tap using the foot or elbow control, to prevent contaminating the tap.

- Wet both hands under running water of a suitable temperature.

- Apply a suitable antibacterial liquid soap from the specially operated dispenser, and wash all areas of both hands and wrists thoroughly – this should take up to 30 sec to carry out correctly.

- Nailbrushes are not advised unless they are autoclavable, as they can become contaminated with repeated use.

- Rinse both hands under running water, holding them up so that the water does not flow back over the fingers.

- Dry the hands thoroughly, using single-use disposable paper towels.

- Heavy-duty gloves must be worn when the cleaning of dirty instruments is being carried out.

- Clinical gloves must be worn whenever patients are being treated, and discarded between patients. These should be non-powdered and of a non-latex material, such as nitrile or vinyl, to avoid the development of skin sensitisation conditions.

Whenever an invasive surgical procedure is to be carried out (oral, periodontal or implant surgery), the hand-washing procedure described above should be extended to include the forearms and should be carried out for a minimum of 2 min to be completed effectively. Special surgical-grade hand wash should be used, with a sterile, single-use scrubbing brush.

At the end of the cleaning, the hands should be held up during rinsing to allow the water to drain off the elbows, and then the hands and forearms should be dried with sterile paper towels. Sterile gloves should then be placed on both hands. This ‘scrubbing-up’ procedure is known as the surgical (aseptic) technique of hand washing.

Use of personal protective equipment

Personal protective equipment is worn to prevent staff from coming into contact with blood and other bodily fluids, and its correct use should be stipulated in the infection control policy.

It is a legal requirement for dental employers to provide the following protective clothing for their staff (Figure 8.3).

- Gloves of varying quality (clinical or household), as discussed above.

- High-temperature wash uniform, to be worn in the work area only.

- Plastic apron to be worn over the uniform when soiling may occur during surgical procedures or while cleaning the surgery.

- Safety glasses or goggles, to prevent contaminated material entering the eyes.

- Prescription glasses should be further protected by wearing a visor or face shield.

- Visors or face shields alone do not provide adequate protection to the eyes, nor prevent the inhalation of aerosol contaminants without the use of a facemask.

- Facemasks of surgical quality should be worn whenever dental handpieces or ultrasonic equipment is in use, to prevent the inhalation of aerosol contamination and pieces of flying debris.

Alcohol-based hand gels should not be used with clinical gloves, as they can damage the nitrile or vinyl material, allowing leakage to occur. Household gloves can be safely washed with detergent and hot water, then left to dry naturally.

There has been no change in the recommended use of PPE following the publication of HTM 01-05.

Cleaning of the clinical area

The whole of the dental practice should be cleaned to a socially acceptable standard on a daily basis, and this is usually carried out by a domestic cleaner. In clinical areas, however, a far higher standard of cleaning is necessary because these are the areas where contamination of the environment by body fluids is greatest, and where the highest chance of cross-infection is likely to occur.

Figure 8.3 Personal protective equipment – examples.

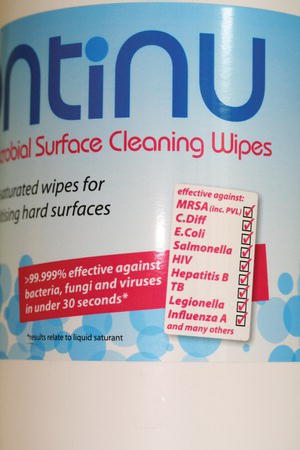

Figure 8.4 Disinfectant cleaning product.

The standard to be achieved in the clinical environment is that of disinfection. This involves the use of various chemicals to inhibit the growth of, or ideally kill, bacteria and fungi (Figure 8.4). However, most are not effective against bacterial spores or some viruses.

Those in common use in the dental workplace include the following.

- Bleach-based cleaners – containing sodium hypochlorite and used to disinfect all non-metallic and non-textile surfaces, and to soak laboratory items.

- Aldehyde-based cleaners – can be used on metallic surfaces and to soak laboratory items.

- Isopropyl alcohol wipes – to disinfect items such as exposed x-ray film packets for safe handling during processing.

- Chlorhexidene gluconate – as an irrigating disinfectant during root canal treatments, and as a skin cleanser.

The practice as a whole should be kept clean, dry and well ventilated. Some workplaces have air conditioning installed, but care should be taken that the system does not recirculate the contaminated surgery air. In addition, special precautions are required to ensure that the air conditioning unit does not become contaminated with the waterborne micro-organism Legionella.

A written protocol for surgery cleaning should be available in all dental workplaces, which lays out the correct procedure in a logical manner and details how each item should be dealt with. In general, it should include the following.

- All work surfaces should have the minimum items of equipment out for each procedure, and when these items are not in use they should be stored in drawers or cupboards to prevent aerosol contamination.

- Areas should be designated as ‘clean’ and ‘dirty’ so that dirty used instruments are not placed where clean items should be – this is called zoning.

- Equipment likely to be contaminated, such as chair and light controls, and headrests, should be covered with impervious plastic sheets (such as ‘Clingfilm’) and changed between patients – this is called using protective barriers.

- Dental aspirators which exhaust outside the surgery area will reduce the risk of aerosol contamination; they should be used routinely and flushed through daily with a recommended non-foaming disinfectant.

- Clinical records and computer keyboards should not be handled while gloves are being worn.

- All non-metallic equipment can be wiped down with a bleach-based preparation, which is particularly effective against viruses, at the end of each day.

- Bleach-based disinfectants cannot be used on metallic items as they will corrode the metal.

- All intraoral radiographs should be wiped with an isopropyl alcohol (IPA) wipe before being handled with clean gloves and taken for processing.

- Reusable digital devices must be decontaminated in accordance with manufacturers’ instructions and then sterilised.

Most of these disinfectant products are sold as convenient sprays or presoaked wipes, but bleach products have to be made up on a daily basis as a fresh solution. This is because the chlorine content is lost over the day so that the resulting solution becomes weaker, and cannot then be assumed to be strong enough to act as a viricide. Bleach also has to be used with caution on any fabrics as it will remove the colour, and it has an unpleasant smell and taste.

The uses of bleach-based disinfectants are as follows.

- 1% fresh solution to disinfect all non-metallic, non-fabric surfaces within the surgery.

- 1% fresh solution to disinfect impressions and removable prostheses before transferring between the patient and the laboratory.

- Up to 10% fresh solution to clean blood spillages within the surgery.

As all disinfectants are poisonous if ingested, their manufacture and usage are strictly controlled by the COSHH legislation, which is discussed in detail in Chapter 4.

HTM 01-05 implications – clinical area decontamination

The key issue of reducing the risk of cross-infection has brought about the following updates.

- The protocol in use for cleaning of the clinical areas should be written down and should clearly outline the steps to be taken by staff for the decontamination procedure.

- All surfaces and equipment should be impervious (resistant to fluids) and easily cleanable.

- Work surfaces and floor coverings should be continuous so no joints should occur between sections of the surface and with the walls of the room (Figure 8.5).

- The clinical area should be cleaned after each session using:

- disposable cloths or clean microfibre material

- water to wet cloths

- detergent.

- Commercially available bactericidal cleaning wipes and sprays can also be used to reduce any viral contamination of work surfaces, between patients (Figure 8.6).

- Alcohol wipes, although active against viral contamination, should be used as the sole cleaning agent with caution, as they may actually seal protein-based contaminants onto the surface.

- Alcohol is not a suitable cleaning agent for use on stainless steel surfaces, for the above reason.

- Wherever possible, covers should be used on as many chairside items as possible, as an effective barrier against contamination. In particular, computer keyboards must be covered during clinical sessions.

- Cleaning of all the following should occur at the end of each patient treatment, or have barrier covers changed after single use.

- Work surfaces in close proximity to the dental chair

- Dental chair and control panel

- Bracket table/trolley/delivery unit

- Aspirator unit and spittoon

- Inspection light and handles

- X-ray unit if in close proximity to the dental chair.

Figure 8.5 Sealed work surface detail.

Figure 8.6 Example of surface cleaning spray.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses