Occlusal-plane canting is a challenging problem for orthodontists because it cannot be solved easily without surgical intervention. Normally, a LeFort I osteotomy and concomitant mandibular surgery is used to correct the problem, even in patients with mild facial asymmetry but with noticeable occlusal-plane canting. Skeletal anchorage can be used in patients with occlusal canting to reduce the need for orthognathic surgery. The purpose of this article was to introduce a biomechanical system—rhythmic wire— to correct occlusal-plane canting. The records of 2 patients treated with this system are shown.

The cant of the occlusal plane in the frontal plane can be the result of skeletal asymmetry of the jaw bones or the asymmetric vertical position of anterior or posterior teeth. Before the advent of skeletal anchorage in orthodontics, the correction of occlusal-plane canting had only limited indications, whether the origin was skeletal or dental. Therefore, surgery was considered the only method for correcting this problem. However, skeletal anchorage has made possible true intrusion of molars, which was difficult with conventional orthodontic means. Moreover, it is now possible to correct occlusal-plane canting by controlling the vertical position of the molars.

It was reported that all people have some craniofacial asymmetry, even in esthetically normal or pleasing faces. In addition, an occlusal cant in most normal patients might be too small to detect. Padwa et al reported that 4° is the threshold for recognizing an occlusal cant. However, they measured occlusal-plane canting from a horizontal line connecting the supraorbital rim. In our experience, patients often recognize their occlusal canting as being unpleasant esthetically when there is a discrepancy in parallelism between the lip line and the occlusal plane. In some patients with vertical asymmetry of the right and left posterior teeth without anterior occlusal-plane canting, the occlusal canting becomes obvious after orthodontic leveling. Facial asymmetry that is too minimal for orthognathic surgery but accompanies recognizable occlusal canting can be corrected by skeletal anchorage-reinforced orthodontic treatment. However, few biomechanical systems use skeletal anchorage to correct occlusal canting.

We developed a biomechanical system called “rhythmic wire,” which consists of 2 miniscrews (on the maxillary and mandibular teeth), intrusion wire, extrusion wire, transpalatal arch, and lingual arch. This report presents the use of this method in 2 patients for correcting the occlusal cant to avoid or minimize orthognathic surgery.

Rhythmic wire

Rhythmic wire was initially developed to control the vertical position of the posterior teeth and consists of intrusion rhythmic wire and corresponding extrusion rhythmic wire. In addition, a transpalatal arch or a lingual arch can be applied if there is a need to control the third-order torque of posterior teeth that face an intrusion or extrusion force. Rhythmic wire can also be a good option for patients with palatally or lingually tipped posterior teeth because buccal tipping of the teeth can occur without a transpalatal or lingual arch.

The intrusion wire is formed with 0.019 × 0.025-in beta-titanium alloy straight wire of appropriate length (usually the length between the first premolar and the second molar) with hooks on each end for engagement to the main archwire ( Fig 1 ). If a decrease in the intrusion force is required, the size of wire can be reduced, or helices can be included. There is no consensus on the optimal force for the intrusion of teeth, but there appears to be some accord between researchers that posterior teeth require more force than anterior teeth. Kalra et al used 90 g of force per posterior tooth, Park et al suggested 150 to 200 g, Umemori et al recommended 500 g, and Melsen and Fiorelli used 50 g buccolingually per posterior tooth. The intrusion wire is placed on the vestibular side of the miniscrew, which is generally placed between the second premolar and the first molar, and each end is activated to engage the main archwire ( Fig 1 ). The point where the hooks of the intrusion rhythmic wire engage depend on the clinical need; this means that the clinician can choose the site to apply the force and change the site by adjusting the intrusion wire without replacing the miniscrew. The miniscrew should have an undercut in its head design to place the intrusion wire, and an elastomeric ring can be used to secure the intrusion wire to the miniscrew.

The extrusion rhythmic wire, which is placed on the opposite dentition, is made from stainless steel wire (or cobalt-chromium wire with heat treatment) in a clover-like form ( Fig 2 ). An indentation is prepared on the top half circle (vestibular side) to accept the miniscrew head, and each root (occlusal side) has a hook for attachment to the main archwire. Figure 2 shows its configuration and activation. Activation is achieved by manipulation of the horizontal loops. A smaller force than for intrusion is sufficient for extrusion of the teeth. However, to prevent deformation of the wire, its size should be greater than 0.016 in, and stainless steel wire is recommended. Helices or loops can be added to reduce the force ( Fig 3 ). The intrusion and extrusion rhythmic wires should be used simultaneously to maintain the integrity of the occlusal contacts. In addition, the position of the hooks is determined by the clinical situation.

The extrusion or intrusion of molars from the buccal side can cause buccal or lingual crown tipping, which is generally undesirable. To minimize this tipping, a transpalatal or lingual arch can be applied with a rectangular lingual sheath to the active (extrusion or intrusion) side, and a round sheath can be applied to the other side, as described by Rebellato. Also, full alignment, leveling, and space consolidation are recommended before applying a rhythmic wire, and the main archwire should be rectangular stainless steel for more predictable and easy control of the posterior quadrant.

Patient 1

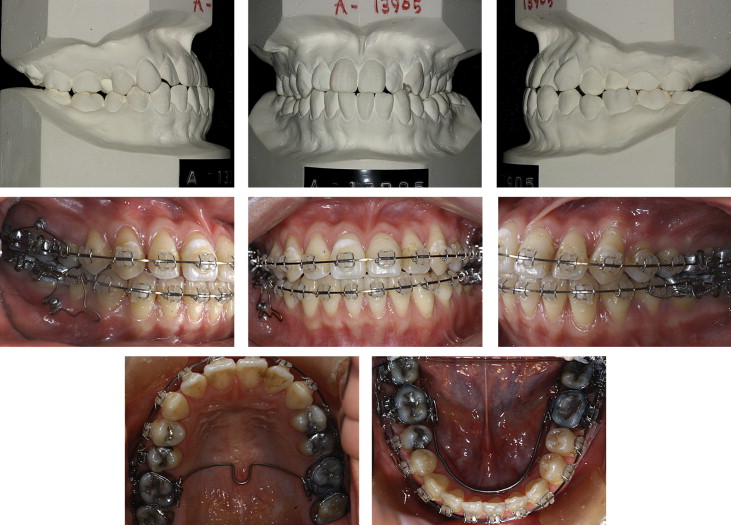

A 20-year-old woman was referred from a local dental clinic complaining of masticatory problems on the left side. The intraoral features showed moderate crowding of her maxillary dentition, an anterior edge-to-edge bite, and a posterior crossbite on the left side ( Fig 4 ). The occlusal relationship was Class II molar and Class I canine on her right side, and Class III molar and canine on her left side ( Fig 4 ). Her maxillary right posterior teeth were positioned vertically low compared with the left side ( Fig 4 ). After reviewing her condition, she was diagnosed with skeletal Class III facial asymmetry and a canted posterior occlusal plane.

Her skeletal problems were mild, and she did not require facial changes. She refused surgery and also declined treatment accompanying the extraction of her premolars. The treatment plan was established to distalize the maxillary right posterior and mandibular left posterior teeth with miniscrews to resolve the crowding and correct the occlusal relationships with rhythmic wire.

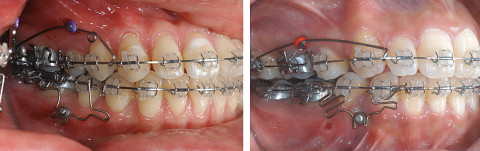

After distalization of the molars, aligning and leveling were performed. The leveling procedure unmasked the posterior occlusal canting and showed an apparent difference in the gingivae between the left and right sides while smiling ( Fig 5 ). It was decided to intrude the maxillary right posterior teeth because of the excessive gingival display on the right side. Miniscrews were placed between the maxillary right second premolar and molar, and between the mandibular right second premolar and molar. An intrusion rhythmic wire was placed on the maxillary right posterior teeth, and an extrusion wire was placed on the mandibular right posterior teeth. In addition, a transpalatal arch and a lingual arch with a rectangular lingual sheath were applied on the right side, and a round sheath was used on the left to control the inclination of the teeth.

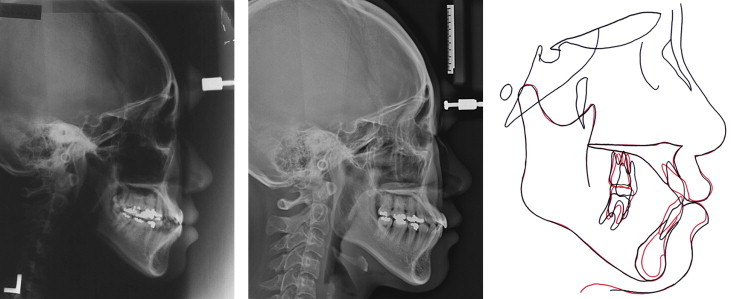

The occlusal cant was corrected by the intrusion of the maxillary right posterior teeth. Finishing and detailing of the occlusion was then performed, and the intruded maxillary right posterior teeth were maintained with wire ligation to the miniscrew. After removing the appliances, a canine-to-canine lingual bonded retainer was placed in the maxilla, and a wraparound retainer was used for the mandible. Superimposition of pretreatment and posttreatment lateral cephalogms showed reductions of the difference in vertical height of the right and left molars ( Fig 6 ).

Distalization of the molars and leveling took 15 months, correction of the occlusal cant with rhythmic wires took 9 months, and finishing took 4 months. Overall, the total active treatment period was 28 months.

Patient 2

A 22-year-old woman visited the orthodontic department of Kyunghee University complaining of crowding of her maxillary teeth and protrusion of her lips. The intraoral examination showed maxillary and mandibular anterior crowding, and the facial examination showed a canted occlusal plane with asymmetric elevation of the right and left corners of the mouth during smiling that exaggerated the occlusal canting ( Figs 7 and 8 ). The treatment plan was to extract the first premolars to resolve the crowding and lip protrusion and to apply rhythmic wire to correct the occlusal canting.