18.2.1 The First Pure Surgical Two-Stage Protocols for Palatal Repair

It was Herman Schweckendiek (1955) from Marburg, Germany, who, in the early 1950s, first described a true surgical two-stage palatal repair method (Fig. 18.1b), which, over time, was employed in a great number of CLP patients. Even today, the two-stage protocol sometimes is referred to as the “Schweckendiek method,” though, presently, important details of the original description are no longer advocated and new features have been added. Follow-up reports from the German cleft center by the originator’s son, Wolfram Schweckendiek (1978, 1981a, b), described great satisfaction with the devised regimen, both regarding the patients’ speech development and their long-term maxillary growth. However, when an outside team examined some of the Marburg patients, they could only confirm the highly acceptable facial growth (Bardach et al. 1984). Regarding speech outcome of the investigated sample, an unusually high incidence of velopharyngeal incompetence (VPI) was found, most likely due to a short soft palate with poor mobility.

In the 1950s, Slaughter and Pruzansky (1954) from the United States also reported use of two-stage palatal surgery, particularly in patients where the palatal cleft did not lend itself to one-stage repair. They outlined several factors for the team to consider before deciding to perform velar surgery as an initial procedure. Examples of such determinants were width of the cleft, length and mobility of velum, and relation of velum to contiguous areas in nasopharynx. No outcome studies of their method were published, however, which might suggest that the results did not reach up to the authors’ expectation. Although a few American teams began advocating the two-stage palatal surgery protocol in the mid-1960s (Blocksma et al. 1975; Cosman and Falk 1980; Dingman and Argenta 1985), it was mostly in Europe the method gained acceptance. Interest in the protocol was boosted here, in particular after the Zürich cleft team reported favorable outcome following change to the two-stage method in 1967 (Hotz and Gnoinski 1976). When members of the Gothenburg cleft team in the mid-1970s also contemplated change to the two-stage regimen with early SPR followed by later HPR, it was the excellent short-term result from Zürich, which was the precipitating factor for us. At this time, several other Swedish teams began advocating the two-stage protocol as well, while other cleft centers in Scandinavia did not join the group using the protocol until more recently.

18.2.2 American Rejection of the Two-Stage Protocol

In the early 1980s, particularly, speech pathologists from a limited number of American cleft centers questioned the advisability of introducing the two-stage method for palatal repair (Witzel et al. 1984). They maintained that the few papers published on this subject had demonstrated severe speech problems, both before and after HPR. Some surgeons also expressed concerns about the protocol, which they felt not only jeopardized the patients’ speech development, but in addition, it resulted in inferior surgical results. The incidence of fistulas in the repaired cleft region increased significantly, and furthermore, the patients’ occlusion did not improve as much as hoped for (Cosman and Falk 1980; Jackson et al. 1983). Though this criticism was built only on short-term observations with minimal scientific analyses, many surgeons, especially in the United States, chose to abandon the two-stage method. Today, very few American teams appear to advocate the protocol with early SPR and delayed HPR (Katzel et al. 2009).

18.3 Surgical Details Introduced During Development of the Two-Stage Palatal Protocol

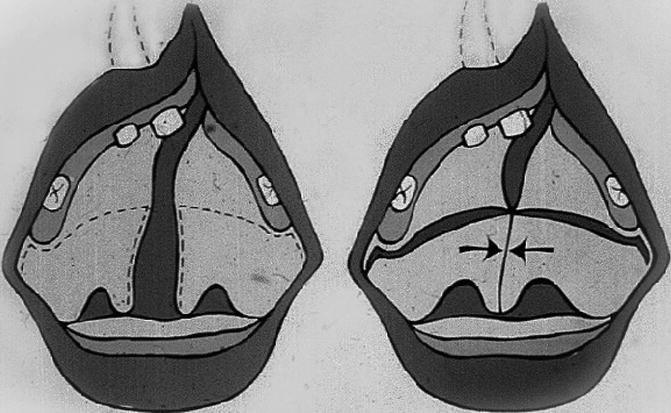

Though Gillies and Fry (1921) had employed surgical separation of part of the soft palate from the posterior edge of the hard palate, Schweckendiek (1955) did not include this important surgical step at the reintroduction of the two-stage protocol. With no detachment of velum at SPR, the repaired soft palate became both short and tight. The younger Schweckendiek (1978) presented schematic drawings, illustrating how tension in the sutured velum could be alleviated (Fig. 18.1b). Before uniting the velar halves, small incisions were made laterally on both sides. The dissections penetrated the soft palate, where a transverse rubber band was inserted. At the end of SPR, it was tightened to reduce tension at the midline stitches. The device was kept in place after surgery for 1–2 weeks. Releasing incisions around the maxillary tuberosities and cutting of hamulus on both sides were other ways trying to deal with the increased tension in the repaired velum.

18.3.1 Modern Methods for Velar Repair

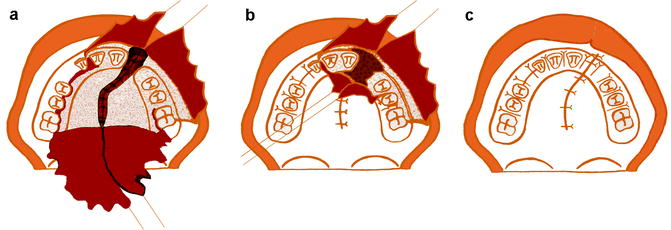

To avoid problems with a short and tight soft palate, surgeons began realizing that velum had to be released from the posterior hard palate (Braithwaite and Maurice 1968). This idea was supported by studies of Kriens (1970), showing that if there is a cleft of the soft palate, the velar muscular complex on both sides is running in an abnormal, anterior-posterior (A-P) direction. Therefore, it seemed logical, not only to detach but also to redirect those muscles to their normal transverse direction. To get access to the attachment of the velar muscles, mucosal/mucoperiosteal flaps were dissected from various positions at or within the posterior hard palate. The muscles were then cut from the palatal shelves, reoriented to a transverse course, and could be joined in the midline in a more posterior position than before. The procedure would be enhanced by addition of a posterior vomer flap (Malek and Psaume 1983), which was sutured to the nasal mucosa of the anterior soft palate (Fig. 18.2). With anterior velum attached to the lower edge of the posterior nasal septum, the soft palate was lifted up to the level of the palatal shelves, which, during healing, helped reduce the size of the remaining cleft of the hard palate.

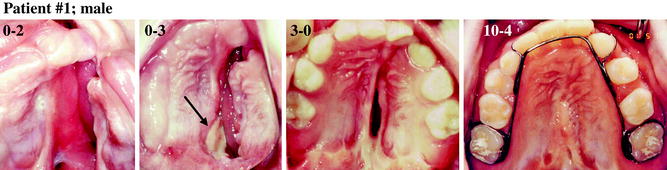

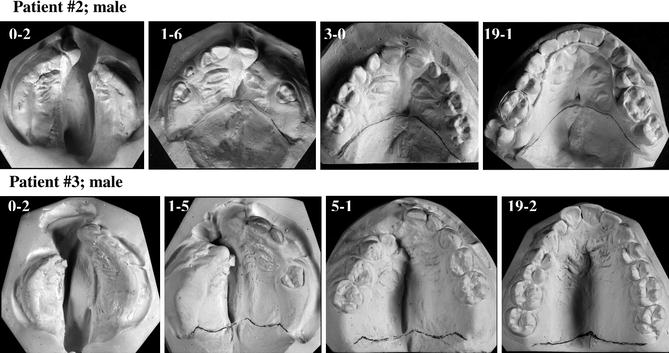

Fig. 18.2

Series of palatal views of a male patient from preoperatively to age 10 years and 4 months. The picture from 3 months shows early healing from where the posterior vomer flap was raised (arrow) and turned backward. Note narrowing of the residual cleft in the hard palate. The HPR added only midline scars

18.3.2 Methods for Repair of Remaining Cleft of Hard Palate

Regarding HPR, Schweckendiek (1955, 1978) did not suggest any particular method for this surgery and only mentioned that, preferably, it should be delayed until around puberty, i.e., when most of maxillary growth was completed. With such late repair of the residual cleft, the chosen method was not as crucial, as if this surgery had been performed at an early age. When later on some surgeons elected to close the remaining cleft already during development of the primary dentition, or sometimes even earlier, different repair methods were utilized. Without any direction from the originators of the two-stage protocol, most surgeons chose to use the same surgical method at HPR, as they were accustomed to in a one-stage palatal procedure. Examples of methods varied from use of uni- or bilateral mucoperiosteal flaps according to methods of Veau, Wardill-Kilner, von Langenbeck, Delaire, or others. Particularly, after use of methods where extensive mucoperiosteal flaps were shifted medially to cover the palatal cleft, areas of bone in the hard palate were left denuded. Growth-restricting palatal scars would then develop, which, depending on the position and size of these scars, had a varying negative effect on maxillary development.

With delay of HPR, the residual cleft usually would narrow considerably (Owman-Moll et al. 1998), which the surgeon should have taken advantage of. The reduced width of the remaining cleft would, in many cases, allow primary repair of the residual opening in the hard palate after mobilization of the cleft edges without leaving any palatal bone denuded. In wider residual clefts, the repair could be accomplished with a turnover vomer flap or by use of bilateral flaps taken from the thin palatal mucoperiosteum close to midline. According to Delaire, inclusion of the thick palatal mucoperiosteum more laterally would cause bare bone in areas with increased risk for development of growth impairing scars (Markus et al. 1993). If the remaining cleft in the hard palate was very wide, it was suggested to postpone HPR until age 2 or 3 years. These surgical details were decisive factors for maxillary development during subsequent growth.

18.3.3 Timing of Palatal Surgery

Timing of repair of the two palatal procedures has also been characterized by great variation. Reports from literature have suggested ages varying from 3 to 24 months for SPR, and for HPR, different papers have proposed ages ranging from 6 months to 16 years. The timing preferences of the surgeon and the cleft team most often have been guided by subjective estimations of how the operations might affect speech and/or maxillary growth outcome.

18.3.3.1 Surgical Timing and Speech Development

Regarding speech development, the controversial debate on optimal age for palatal closure has been hampered by questionable comparisons between studies with different timings of surgery without any consideration to other factors, i.e., staging, sequence, or technique for the repair, which will influence the outcome. From theoretical perspective of speech-language development and particularly in relation to the sensitive period or state of readiness for speech development between the ages of 4 and 6 months, there is no controversy that an early, complete palatal closure is preferable (Kemp-Fincham et al. 1990). The early age would mean before or at onset of pertinent canonical babbling and possibility to close the oronasal coupling for relevant development of oral pressure sounds. Both were found to be significant predictors of later speech and language performance (Oller et al. 1998; Chapman et al. 2003; Lohmander and Persson 2008; Scherer et al. 2008). Recent studies indicate that these factors can be reached to a higher degree, if the soft palate is repaired early, even if the cleft in the hard palate still is unoperated (e.g., Willadsen and Albrechtsen 2006). According to opinions published by one of the few American teams, currently advocating the two-stage repair (Rohrich et al. 2000), a protocol, with velar repair at around 3–6 months and delayed hard palate closure at age 15–18 months, would provide the best opportunities for normal speech development as well as favorable maxillary growth outcome.

18.3.3.2 Timing of Surgery and Maxillary Growth

Considering the growth influence from palatal surgery, our view is that possible effects from various timings, for SPR as well as HPR, depend upon whether the employed surgical methods will impair palatal areas, important for subsequent maxillary development. If using a method with definite propensity for growth restriction, an early repair should be delayed or preferably not be used at all. But, if surgery can be accomplished with minimal denudation of palatal bone in sensitive regions (Markus et al. 1993), the growth outcome of the procedure can be quite satisfactory even if performed during the patients’ first year of life. These circumstances have seldom been considered, which has contributed to controversies about the benefits of the two-stage method for palatal repair.

18.4 Reported Speech and Growth Outcome After Some Variants of the Two-Stage Palatal Protocol

After introduction of a new philosophy for solving a specific surgical problem, such as repair of cleft palate, many surgeons tend to “jump on the bandwagon,” and furthermore, some of them might devise their own treatment variants. When the two-stage palatal repair protocol was reintroduced in the 1960s and 1970s, many cleft teams converted to this regimen. Unfortunately, the majority of those early teams, including the operating surgeons, did not disclose, whether the new regimen had fulfilled their expectations or not. A few short-term reports were published in the 1980s, where the outcome generally was rated as poor.

18.4.1 Speech Outcome

Speech development, sometimes appraised before HPR, was judged as inferior to what was expected. These young children had significantly poorer articulation skills than their noncleft peers. Posterior substitutions had often developed and so had frequent VPI (Cosman and Falk 1980; Jackson et al. 1983; Noordhoff et al. 1987). From a methodological point of view, it has to be remembered that these evaluations were clinical, live judgements with no possibility for control of the data. If we believe that, even so, these early assessments were valuable, we suspect that many of the speech errors might have had their origin in missing important surgical details at closure of the soft palate. For instance, one of the papers stated, “the soft palate was closed directly with only minimal division of nasal mucosa and palatine aponeurotic fibers” (Cosman and Falk 1980). With no definite separation between the soft and hard palate, we suspect the surgeon had been unable to bring back the repaired velum to a position needed for achievement of velopharyngeal competence (VPC) on a regular basis. In other studies (Noordhoff et al. 1987), it was mentioned that SPR had been performed according to the original method of Perko (1979), but nothing was reported about use of a posteriorly based vomer flap. Omission of this crucial surgical step is likely to have caused reduced velar length in many cases and also a wider residual cleft in the hard palate due to less narrowing during early palatal growth. Tentatively, the short soft palate would increase the risk for VPI and posterior substitutions, such as pharyngeal and/or glottal articulations. In the report by Noordhoff et al. (1987), all patients treated with the two-stage method were said to have increased articulation errors, particularly those individuals with wide remaining cleft of the hard palate. A later follow-up paper (Liao et al. 2010) confirmed increased hypernasality and compensatory articulation disorders in these patients.

18.4.2 Maxillary Growth Results

More recently, a number of teams have, in particular, reported the patients’ maxillary growth outcome with limited focus on their speech development. The majority of the papers described favorable midfacial growth (Noverraz et al. 1993; Tanino et al. 1997; Nollet et al. 2005, 2008; Sinko et al. 2008; Liao et al. 2010), while a few of the reports did not find any maxillary growth advantage of the two-stage protocol (Gaggl et al. 2003; Mølsted et al. 2005; Holland et al. 2007; Stein et al. 2007). The first group of papers generally advocated methods for SPR and especially for HPR, where closure of the cleft resulted in minimal denudation of bone in the palate. Examples of such procedures comprised employment of a turnover vomer flap, suturing of the cleft edges, mobilization of mucoperiosteal flaps dissected close to the cleft, or use of a modified von Langenbeck operation. On the other hand, in studies describing no maxillary growth benefits or inferior maxillary development, the methods used in these patients had created growth-restricting scars, mostly from HPR. Examples of surgical methods included employment of a Veau pedicle flap, a mucoperiosteal pushback procedure, or use of “unipedicled mucoperiosteal flaps.” All of them will give rise to significant areas of bare palatal bone, which will heal secondarily, leading to scar tissue development. Thus, these different opinions about definite growth advantage or insufficient maxillary development after the two-stage palatal protocol can be explained by the performed repair methods and, only to a limited extent, by when surgery was done, as described above. Such explanations are easier to embrace than speculation about effects, e.g., from cleft team organization (Shaw et al. 1992a, b) or surgeons’ different operating skills (Ross 1987a, b), as reasons for the patients’ growth results. However, we have to remember that acceptance or rejection of the two-stage regimen might be influenced not only by how well the repaired maxilla will develop but also by other factors, such as increased risk for fistula formation, poor speech development, and need for more velopharyngeal flaps (VPFs); etc.

18.5 Outcome of Maxillary Growth as Well as Speech from Teams with Long-Term Records

Only a limited number of publications exist, where the patients’ maxillary growth as well as their speech development after two-stage palatal surgery has been studied up to adolescence or early adulthood. From this very small group of papers, we have chosen to report treatment outcome in unilateral cleft lip and palate (UCLP) patients from two European cleft teams still practicing the protocol.

18.5.1 Zürich, Switzerland

In Zürich, Switzerland, the cleft team has used their version of the two-stage palatal repair protocol since the late1960s. It was built on a systematic coordination between maxillary orthopedics and surgical interventions from early infancy (Hotz and Gnoinski 1976; Hotz et al. 1986). The team initiated preoperative maxillary orthopedic treatment shortly after birth, not only to help feeding but also for growth guidance of the maxillary segments. After lip repair at age 5–6 months, the infant continued with maxillary orthopedics until SPR, which was carried out at around 18 months. This surgery included reorientation of the velar muscles after their separation from the posterior hard palate (Perko 1979). The covering flaps of the oral mucosa were dissected from the posterior third of the hard palate, and, to reduce risks for maxillary growth impairment, the dissections were made supraperiosteally. A posterior vomer flap was also raised, and after turning it backward, the flap was sutured as part of the anterior nasal layer at SPR (Hotz et al. 1986). With the nasal mucosa not separated from the posterior hard palate, inclusion of the vomer flap would not help elongate the soft palate, and therefore, a midline Z-plasty was added. At age 5–6 years, HPR was performed. Due to narrowing of the residual cleft, closure was accomplished by use of a turnover vomer flap for the nasal layer, and for repair of the oral layer, a mucoperiosteal flap was shifted medially from the noncleft side.

18.5.1.1 Follow-up Studies

The Zürich cleft team has published several follow-up investigations, particularly about maxillary growth. Roentgencephalometric results from a group of 10-year-olds born with UCLP indicated satisfactory A-P relationship between maxilla and mandible in about 80 % of the subjects (Gnoinski 1990). At age 15–20 years, these patients showed continuation of the favorable orofacial development, documented in the 10-year sample (Gnoinski 1991; Gnoinski and Haubensak 1997). Even if the cleft maxilla grew slightly in length also between 15 and 20 years of age, the average maxilla was shorter than in noncleft subjects. Only about 10 % of the patients needed maxillary orthognathic surgery to achieve an acceptable facial profile.

The team from Zürich has also reported cross-sectional, detailed speech data based on live assessments. After HPR and speech therapy, the patients’ glottal or pharyngeal articulations were eliminated (Hotz et al. 1978). This outcome was in contrast to what was achieved with the previous treatment protocol. Nothing was mentioned about development of retracted articulations of certain consonants such as anterior plosives. Severe hypernasality decreased spontaneous with age, even before HPR was performed. After HPR, this speech error was claimed by the authors to have disappeared almost completely, often though, with help of intensive speech therapy. No pharyngeal flaps were judged by the team to be necessary in any of the Zürich patients.

18.5.1.2 Verification of the Zürich Speech Outcome

An outside investigator was recruited to verify the satisfactory speech development of the cleft children in Zürich (Van Demark et al. 1989). Thirty-seven UCLP patients were studied in a cross-sectional investigation at ages ranging from 6 to 16 years (mean 10.5 years). Oral examination generally revealed a mobile and fairly long soft palate, which was ascribed to the surgical method used for SPR. A comprehensive, independent speech analysis from audio recordings revealed that about 95 % of the patients displayed adequate or marginal VPC. The majority of subjects did not show speech errors such as glottal stops and pharyngeal substitutions. Even in the younger patients, the incidence of other compensatory articulations and “nasalizations” was low. The authors concluded that “good speech results for unilateral complete cleft lip and palate can also be achieved with late closure of the anterior palate, at least as done by the Zürich approach.” Unfortunately, no further follow-up has been published.

18.6 Gothenburg, Sweden

When we planned the palatal surgery in our new protocol, the Zürich group had neither published any suggested ages nor detailed descriptions of their surgical procedures. For velar repair, we opted for an age around 6–8 months, while we wanted to delay closure of the remaining cleft in the hard palate to the mixed dentition. Regarding surgical details for SPR, we chose the approach to separate soft palate from hard palate right at the border region (Friede et al. 1980) (Fig. 18.3). The lateral incisions and denudation of palatal bone were to be made as minimal as possible. The velar muscle bundles should be united in the midline after complete release of the muscular fibers from their abnormal insertion at the posterior border of the hard palate. The muscles remained attached to the nasal mucosa. At this stage of development of our method for velar repair, no posteriorly based vomer flap was raised and attached to the anterior soft palate. Therefore, the residual cleft of the hard palate did not narrow as much as expected. This made our surgeon dissect the palatal flaps further anteriorly, occasionally into the middle of the hard palate (Fig. 18.4). Such change would reduce the remaining cleft size and thereby enhance early speech development. However, after some time, we realized that this change in surgical detail at SPR also might restrict maxillary growth. It was first after introduction of the posterior vomer flap that the dissection line in the palatal mucosa returned to its previous position close to the edge of the hard palate. The Zürich surgeon Perko (1979) did not report in detail how their two-stage surgical procedures were carried out until 1979, and then, a posteriorly based vomer flap at SPR was not yet part of the Swiss surgical routine. It took another 1 or 2 years before many surgeons, including those from Zürich and Gothenburg, began utilizing this important addition to SPR.

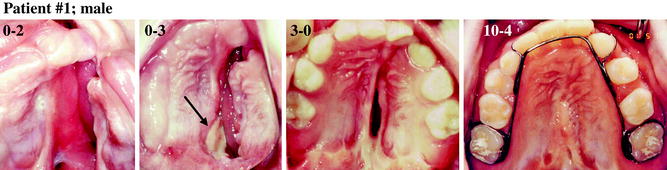

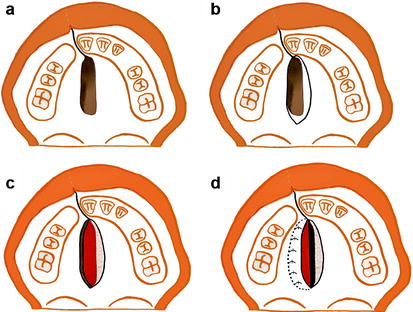

Fig. 18.3

Schematic illustration of SPR according to an early repair version used at Gothenburg Cleft Center. Incision lines run in the border region between velum and hard palate. The two halves of the soft palate, with the muscle bundles reoriented to a transverse course, are united in the midline (arrows)

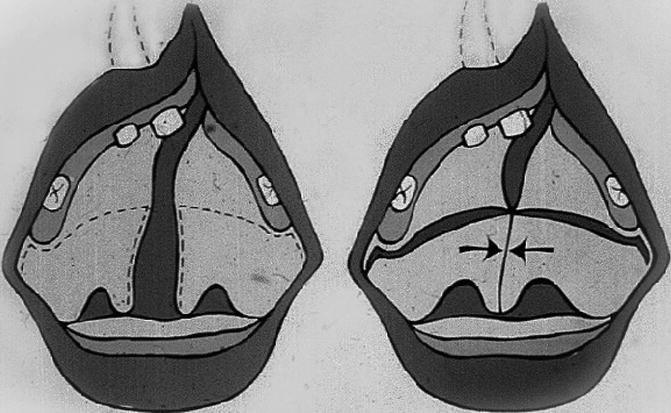

Fig. 18.4

Anterior-posterior variation in position of scar line from SPR. In upper patient, the scar line is too far forward, harming growth in length of the maxillary dental arch. In lower patient, the scar line is in correct position at posterior maxilla. The dental arch length is well developed with space for all teeth

18.6.1 More Detailed Two-Stage Palatal Surgery

In 1996, our cleft team published a detailed report how the two-stage protocol was practiced in Gothenburg up to 1995 (Lilja et al. 1996). At soft palate surgery, incisions began around the posterior part of the maxillary tuberosities and then followed a zigzag route at the posterior border of the hard palate (Fig. 18.5). A posteriorly based vomer flap was dissected. Anteriorly, the incision was placed behind the vomero-premaxillary suture, and the flap had its base close to the junction between vomer and the cranial base. Mucosal flaps in the soft palate were raised by blunt dissection. Hamulus was identified but not broken. The insertions of velar muscles, including their attached nasal mucosa, were cut at the posterior border of the hard palate. A flap with the muscles connected to the nasal layer was then dissected free and mobilized to a posterior position. After that, the muscles including the levator were reconstructed to a transverse course, where suturing could be performed without tension. The vomer flap was raised and the nasal layer of velum was closed anteriorly to the level of the muscular sling by use of the vomer flap. In this way, the vomer bone became connected to the anterior velum. The palatal closure was then continued over to the oral side, where a pushback procedure was performed within the oral layer of the soft palate. Inclusion of the vomer flap as well as the pushback surgery helped to increase the length of the repaired velum.

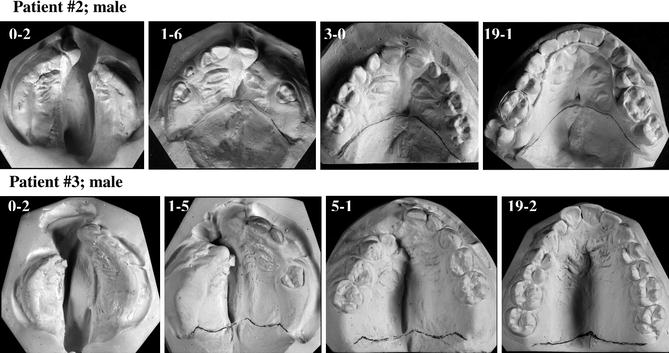

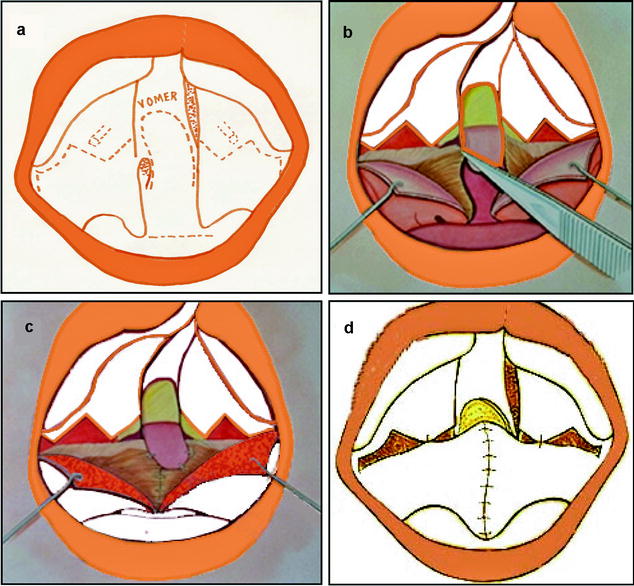

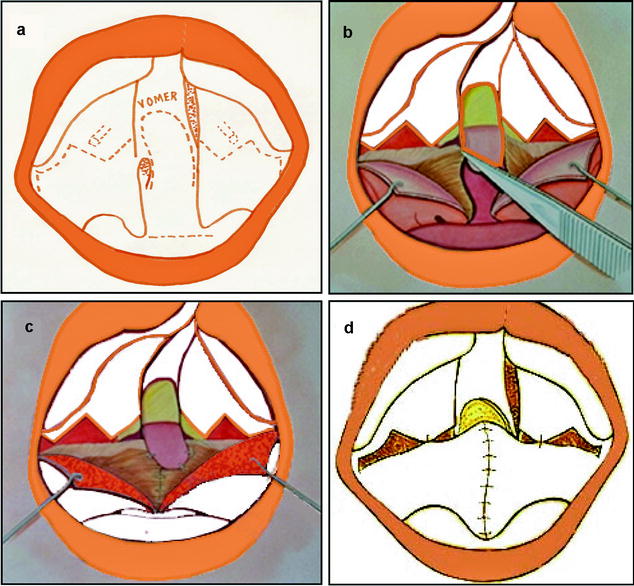

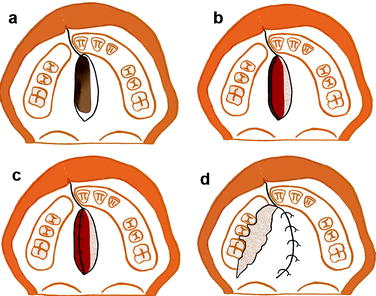

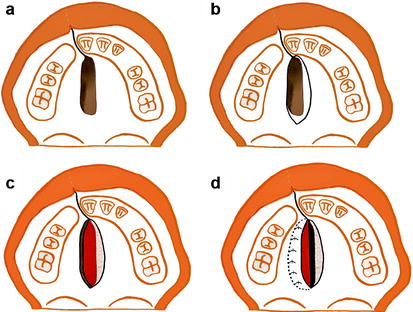

Fig. 18.5

Schematic drawings of the soft palate closure. (a) The incisions follow a zigzag line between the soft and hard palate. A posterior vomer flap is dissected, which has its base at the posterior-cranial part of vomer. (b) Both sides of velum are divided into two layers: the oral mucosa and the nasal mucosa with the forward inserting muscle bundles attached. The two layers are separated laterally and posteriorly to the uvula. Medially, the nasal layer with the muscle bundles is cut bilaterally from the posterior hard palate. (c) The muscles are redirected to a transverse course, sutured together medially in a posterior position, and also attached anteriorly to the backward-turned vomer flap. (d) The muscles and the raw surface of the vomer flap are covered by the oral flaps, which are pushed in a medial-posterior direction

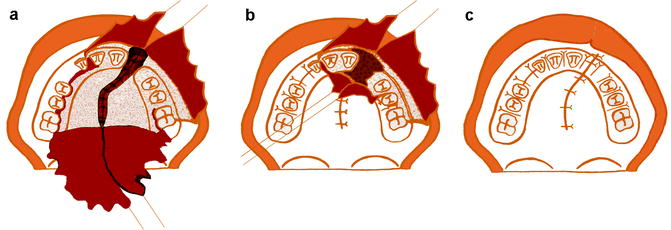

The HPR was delayed until the patient had reached the stage of early mixed dentition (7–9 years), because, thereby, the procedure could be combined with bone grafting to the alveolar cleft. Surgery began with gingival incisions along the neck of the teeth on the palatal side and in part also labially (Fig. 18.6). In the area of the cleft, incisions were made along the cleft edges, and gingival and palatal mucoperiosteal flaps were raised. On the labial side, a back-cut was made in the cleft-side molar area. This facilitated mobilization of the gingival flap as well as the dissection in the cleft area. When the cleft had been dissected completely free on both palatal and labial side, suturing in the midline began in the nasal layer and continued orally in the midline palate. Cancellous bone was then grafted to the cleft in the alveolar process and covered with gingival and palatal flaps. The operation was completed with suturing the gingival and palatal mucoperiosteal flaps together in some interdental spaces. We consider the palatal incisions along the necks of the teeth very important. Because of the reduced width of the residual cleft, suturing back of the combined palatal flaps along the dental arch could be done with none or only minimal palatal bone exposed close to the teeth. In 1996, timing for HPR was modified in an effort to prevent development of typical retracted oral speech deviations noted in some patients during preschool and early school age. The repair was then changed to be carried out around 3 years, which meant an extra operation, because HPR could no longer be performed together with the bone grafting procedure. If the residual cleft of the hard palate was narrow or of average size, it was closed in one layer by use of a simple turnover vomer flap (Fig. 18.7). This approach did not work so well for wider residual clefts of the hard palate due to increased risk for fistula development. In these cases, a two-layer repair was necessary. A vomer flap was then sutured to the nasal mucosa on the cleft side, and the suture line was closed with a mucoperiosteal flap from the cleft side of the palate (Fig. 18.8).

Fig. 18.6

Illustrations of the method for repair of the residual cleft in the hard palate in combination with bone grafting. (a) Incisions are made along the necks of the teeth and along the edges of the residual cleft. Palatal and gingival mucoperiosteal flaps are raised. The nasal layer is closed. (b) The palatal mucoperiosteal flaps are closed in the palate. Bone grafting is performed to the cleft in the alveolus. (c) The grafted bone is covered by gingival and anterior palatal mucoperiosteal flaps, which are sutured together

Fig. 18.7

Composite of drawings illustrating repair of a small- or average-sized residual cleft in the hard palate at age 3 years or preferably earlier. At this stage, bone grafting is not performed in connection with the HPR as shown in Fig. 18.6. (a) The residual cleft in the hard palate. (b) Incision lines. On the noncleft side, the incision goes into the flat medial part of the palate. On the cleft side, the incision is made at the cleft border between oral and nasal mucosa. (c) The vomer flap is raised. It contains some millimeters of oral mucosa leaving a raw bone surface in the medial part of the palate on the noncleft side. On the edge of the cleft side palatal shelf, a subperiosteal dissection is performed and a pocket is created between the oral periosteum and the bone. (d) The vomer flap is tucked into the pocket and sutured, which finalizes HPR. Thus, this is a one-layer closure, and the raw surface of the vomer flap is left for secondary epithelialization

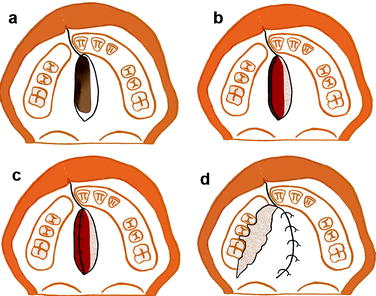

Fig. 18.8

Drawings illustrating HPR in an individual with a somewhat wide residual cleft. Preferably, the patient should have erupting/erupted upper deciduous molars, which usually means an age at around 3 years. (a) Incision lines. On the noncleft side, the incision goes into the flat medial part of the palate. On the cleft side, the incision is made at the cleft border between oral and nasal mucosa. (b) The vomer flap is raised. It contains some millimeters of oral mucosa leaving a raw bone surface in the medial part of the palate on the noncleft side. (c) On the cleft side, a subperiosteal dissection is performed, and the nasal layer is lifted and brought in contact with the vomer flap and sutured. (d) Also on the cleft side, an oral mucoperiosteal flap is raised via an incision along the teeth. The flap is brought in contact with the incision on the noncleft side and sutured. The suture line between the vomer flap and the nasal layer is now covered. The raw bone surface is left for secondary epithelialization, which takes place on a surface with thin neighboring wound edges. Thereby, the risk for bad scar contraction is small

18.6.2 Follow-up Studies of Maxillary Growth

Over the years, the Gothenburg cleft team has reported several follow-up studies, both regarding maxillary growth and speech development. An early growth comparison at age 7 years, before HPR in the two-stage protocol, demonstrated significantly improved results in comparison to what was achieved with our previous regimen (Friede et al. 1987

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses