This article describes the nonextraction treatment of a girl in the late mixed dentition with a severe arch-length deficiency. Rapid maxillary expansion and molar distalization were combined with a lip bumper in the mandible, followed by fixed appliances. Although the literature has reported a high rate of relapse with this method of treatment, excellent stability was achieved at 5 years 3 months posttreatment. The merits of extraction vs nonextraction treatment and stability are discussed.

Arch-length deficiency is a common problem in orthodontics. Clinical signs of tooth-size–arch-length discrepancy are crowding, impaction, and incisor proclination. The controversy persists over whether to increase the size of the arch by expansion or decrease the size of the teeth by interproximal enamel reduction or extraction to resolve the discrepancy. Tooth extraction, an efficient way to resolve crowding, can have detrimental effects on facial esthetics if done haphazardly. Furthermore, tooth extraction is not a better guarantee for stability than anteroposterior or transverse arch expansion in the permanent dentition. This case report describes the nonextraction treatment of a girl with a severe arch-length deficiency. The possible issues that led to the long-term stability will be discussed.

Diagnosis and etiology

The patient was a girl, age 11 years, whose chief complaint was an unpleasant smile. Her medical history was noncontributory, and her dental history included routine dental evaluations. She had no restorations, and her oral hygiene was good. The probable cause of her malocclusion was a combination of genetic and developmental factors.

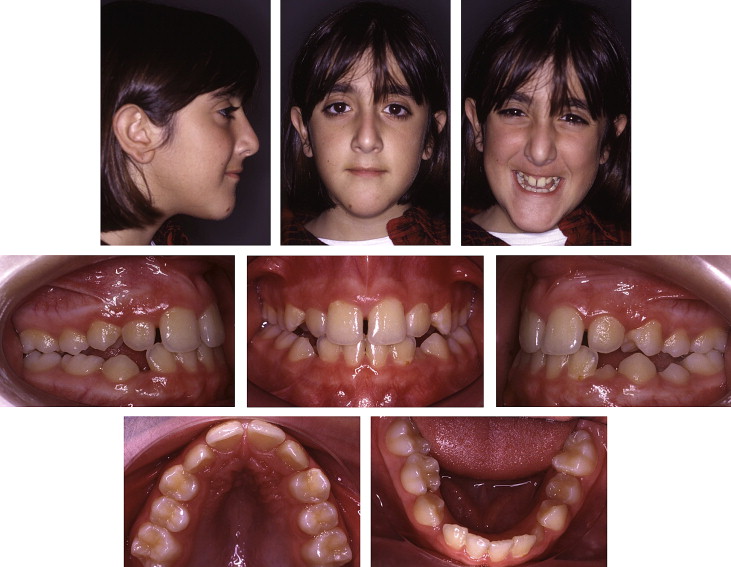

The patient had a straight profile with a tendency to lip retrusion. The nasolabial angle was slightly increased, but the chin extension was adequate. From a frontal view, the face was triangular and symmetrical. The lower lip height (distance from the superior border of the lower lip to the bottom of the chin) was increased relative to the upper lip height. She had competent lips with a thin vermilion. She had normal maxillary incisor vertical display on smiling, but a poor smile arc with the upper incisal curve not running along the lower lip. Transversally, the smile was narrow dentally, displaying the mandibular teeth ( Fig 1 ).

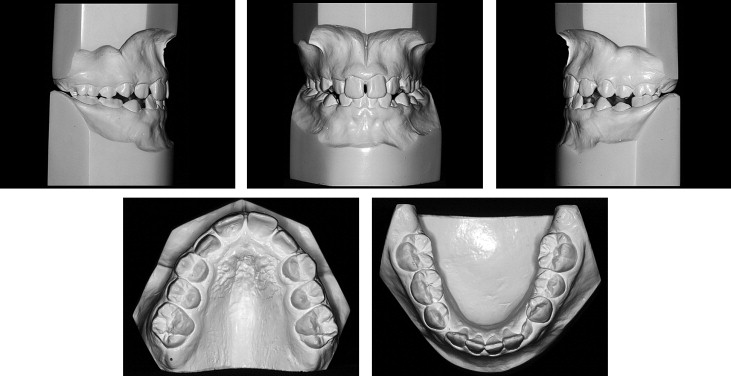

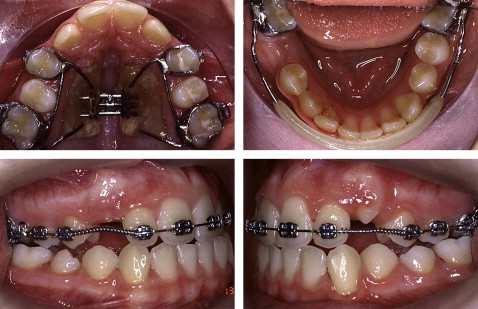

Intraorally, she was in the late mixed dentition stage of development with a persistent mandibular right second deciduous molar. She had an Angle Class I molar relationship on the left side and an edge-to-edge molar relationship on the right side. She had a transverse maxillary deficiency with a transpalatal first molar width of 30 mm. The maxillary arch form was narrow and V-shaped with a high palatal vault. There was no posterior crossbite, but the maxillary posterior teeth were buccally inclined, whereas the mandibular posterior teeth were lingually inclined (dental compensation). The arch-length deficiency was 13 mm in the maxillary arch with no space for the canines to erupt. The mandibular arch was ovoid, and the right canine was also unerupted. The mandibular arch-length deficiency was 7 mm but could be reduced to 4.5 mm if leeway space was gained from the retained deciduous molar with arch-length maintenance. There was a maxillary midline diastema of 1 mm, and both dental midlines were aligned and coincident with the facial midline. The maxillary right lateral incisor was in crossbite. Overjet was normal, and overbite was 50% ( Figs 1 and 2 ).

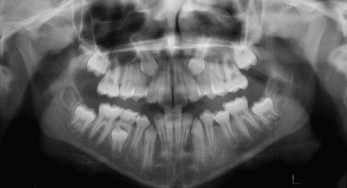

The panoramic radiograph showed a full complement of teeth, including developing third molars. The second molars were not erupted and positioned high in the maxilla. The unerupted maxillary canines were oblique. The roots of the mandibular right second deciduous molar showed 30% resorption, and the succedaneous premolar had 50% root development ( Fig 3 ).

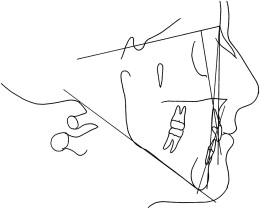

Cephalometric analysis showed a skeletal Class I anteroposterior relationship evidenced by an ANB angle of 4°; the Wits appraisal of –4 mm indicated skeletal Class III compensated by severe hyperdivergence (FMA, 34°; SN-MPA, 50°). The maxillary and mandibular incisors were upright, and the soft-tissue analysis confirmed lip retrusion with an increased value of the Holdaway line to the tip of the nose ( Fig 4 , Table I ).

| Measurement | Norm | Pretreatment (11 y) | Retention (15 y 10 mo) | Posttreatment (21 y 1 mo) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Skeletal | ||||

| SNA (°) | 82 | 76 | 78 | 77 |

| SNB (°) | 80 | 72 | 74 | 73 |

| ANB (°) | 2 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| FH-NA (maxillary depth) (°) | 90 | 92 | 93 | 93 |

| FH-NP (facial angle) (°) | 87 | 88 | 89 | 90 |

| Wits (mm) | 1 | –4 | –1 | 1 |

| SN-MPA (°) | 32 | 50 | 48 | 48 |

| FMA (°) | 25 | 34 | 33 | 33 |

| Dental | ||||

| UI-SN (°) | 103 | 86 | 98 | 98 |

| UI-NA (°) | 22 | 10 | 20 | 21 |

| UI-NA (mm) | 4 | 1 | 4 | 5 |

| LI-NB (°) | 25 | 13 | 32 | 30 |

| LI-NB (mm) | 4 | 3 | 8 | 8 |

| LI-MP (°) | 87 | 72 | 88 | 88 |

| LI-Apo (mm) | 1 | 0 | 4 | 5 |

| UI-LI (°) | 131 | 153 | 126 | 126 |

| Soft tissue | ||||

| Holdaway line (mm) | ||||

| Tip of nose | 9 | 12 | 9 | 5 |

| Subnasale | 5 | 2 | 4 | 7 |

| Upper lip | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Lower lip | 0 | 1 | –1 | –1 |

| Supramentale | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 |

| Pogonion | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Treatment objectives

The main objectives in treating this malocclusion were to reposition the impacted canines and address the arch-length deficiency. The upright incisors would need to be proclined to improve lip support. Transverse maxillary deficiency would also need to be addressed to enhance smile esthetics and width. Finally, ideal overbite and overjet and an optimal posterior intercuspation would need to be achieved.

Treatment objectives

The main objectives in treating this malocclusion were to reposition the impacted canines and address the arch-length deficiency. The upright incisors would need to be proclined to improve lip support. Transverse maxillary deficiency would also need to be addressed to enhance smile esthetics and width. Finally, ideal overbite and overjet and an optimal posterior intercuspation would need to be achieved.

Treatment alternatives

Three treatment options were considered.

- 1.

Extraction of 4 first premolars to allow canine eruption and resolve the severe arch-length deficiency. The main advantage of this treatment option would be a shorter treatment time with no need for patient cooperation. Nevertheless, 4 premolar extractions would not address the upright incisors and the lip retrusion, and might even worsen the profile. Furthermore, by not addressing the initial transverse maxillary deficiency, smile esthetics would not be improved.

- 2.

Extraction of the maxillary first premolars and arch maintenance in the mandible followed by incisor proclination. Class III elastics or a maxillary protraction facial mask (dental forces) would be needed to finish in a Class II molar relationship. This treatment option would address the arch-length deficiency with less adverse effect on the profile than 4 premolar extraction. However, profile and smile esthetics would not be optimized.

- 3.

Nonextraction treatment with rapid maxillary expansion (RME) followed by maxillary molar distalization with headgear and lip bumper in the mandible, and proclination of the incisors. The arch-length deficiency would be resolved by transverse and anteroposterior arch expansion, and both profile and smile esthetics would be enhanced. However, this treatment plan relies heavily on patient compliance. Furthermore, long-term stability is questionable, and some type of long-term or permanent retention might need to be considered.

The nonextraction treatment option was adopted because the patient’s chief concern was facial esthetics. Cooperation and stability issues were discussed with the patient and her parents.

Treatment progress

A tissue-borne appliance with bands attached to the first premolars and first molars was used for RME. The appliance was activated once a day for 24 days; approximately 6 mm of arch widening was obtained at the level of the first molars. The screw was then locked with a double ligature tie, and the expander served as a stabilizer for the next 10 months ( Fig 5 , A ). After stabilization, a mandibular lip bumper was placed with bands attached to the first molars. The persistent deciduous molar was extracted 1 month later to favor distal drifting of the first premolar into the leeway space and allow spontaneous eruption of the right canine in proper alignment ( Fig 5 , B ). The lip bumper was discontinued 20 months later after full eruption of the right second premolar.

Cervical traction headgear was placed after expander removal. The outer bow of the headgear was bent upward to direct the forces (250 g per side) through the center of resistance of the maxillary first molars, generating a translatory distal movement of these teeth. The headgear’s inner bow was expanded to prevent the first molars from getting into crossbite while being distalized into a wider portion of the arch. One month later, the maxillary arch was bonded with edgewise brackets (0.022 × 0.028 in). Compressed coil springs were used to open the needed space for the unerupted canines while proclining the anterior teeth. The headgear was used for 11 months and discontinued when the maxillary canines started erupting, while a Class III molar relationship was achieved ( Fig 5 , C and D ).

The mandibular arch was banded and bonded 15 months after the maxillary arch, when the maxillary canines were erupted completely. A normal progression of archwires was used to level, align, and coordinate the arches. Class II and vertical elastics were also needed to achieve proper anteroposterior occlusal interdigitation. The impacted mandibular third molars were removed during active treatment at 14 years of age. Her cooperation was excellent, and the appliances were removed at age 15 years 10 months—3 years 10 months after the start of fixed appliance treatment.

Retention consisted of a maxillary Hawley appliance worn full time for 24 months, followed by 3 months of nighttime wear. The mandibular retainer consisted of a 0.0215-in twisted wire bonded onto the lingual sides of the incisors and canines. The fixed mandibular retainer could be kept permanently to enhance the long-term stability of the results.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses