This report describes the orthodontic treatment of a 12-year-old girl with transposition of the maxillary left canine and the lateral incisor. Cone-beam computed tomography was used during treatment planning. The transposed tooth positions were corrected with an unconventional orthodontic approach. Treatment alternatives and their clinical concerns are presented.

Transposition is defined as an unusual type of ectopic eruption where a permanent tooth develops in the position normally occupied by another permanent tooth. It is a rare occurrence that affects less than 1% of the population. Transposition affects the maxillary dentition (68.5%-76%) more frequently than the mandibular dentition. The most common type of transposition (55%-70%) is that of the maxillary canine and the first premolar (Mx.C.P1). Twenty-seven percent of Mx.C.P1 patients demonstrate bilateral occurrence. Maxillary canine-lateral incisor transposition (Mx.C.I2) is the second most common type at 20% to 42%, with only 5% having bilateral occurrence.

Peck et al described Mx.C.P1 as an anomaly “resulting from genetic influences within a multifactorial inheritance model.” This was based on an elevated frequency of associated dental anomalies, elevated bilateral occurrence (27%), familial occurrence (11%), and differences between male and female prevalence (females 1.55:1 males). Others have demonstrated elevated frequencies of associated dental anomalies with Mx.C.P1 patients. These associated dental anomalies included hypodontia, submerged deciduous teeth, retained deciduous teeth, and supernumerary teeth.

Unlike Mx.C.P1, it has been hypothesized that the etiology of Mx.C.I2 is more environmental than genetic. Dentofacial trauma in the deciduous dentition, with subsequent drifting of the developing permanent teeth is the most common etiologic factor. There are few reports of familial occurrence or dental anomalies associated with Mx.C.I2 transpositions. The only dental anomaly that has an apparent association with Mx.C.I2 is increased third molar agenesis.

Treatment of Mx.C.I2 depends on many factors. If the central incisor has significant root resorption (either from past dentofacial trauma or due to the ectopically erupting canine), the central incisor can be extracted and the canine moved into its position, as has been reported. Significant restorative work is necessary for acceptable smile esthetics with this treatment plan.

If extractions are indicated because of severe crowding or a desire for a change in the soft-tissue profile, then the following extraction pattern should be considered: the transposed canine and the 3 first premolars in the remaining quadrants. If this option is chosen, it could be necessary to intrude the first premolar next to the lateral incisor so that the height of the gingival margin matches that of the contralateral canine. The premolar crown could then be veneered and brought into occlusal function. It also might be necessary to extract the transposed lateral incisor (rather than the canine) if it has already demonstrated root resorption. Extraction of transposed peg-shaped lateral incisors and substitution of canines has also been described.

Another possibility—leaving the canine and the lateral incisor transposed—is rarely a good esthetic or functional option. The difficulty of resolving the transposition is the risk of root interference as the canine passes distally around the lateral incisor. This interference could lead to significant root resorption and subsequent pathologic tooth mobility of the affected teeth. However, resolving the transposition is ideal for esthetics and function.

Diagnosis and etiology

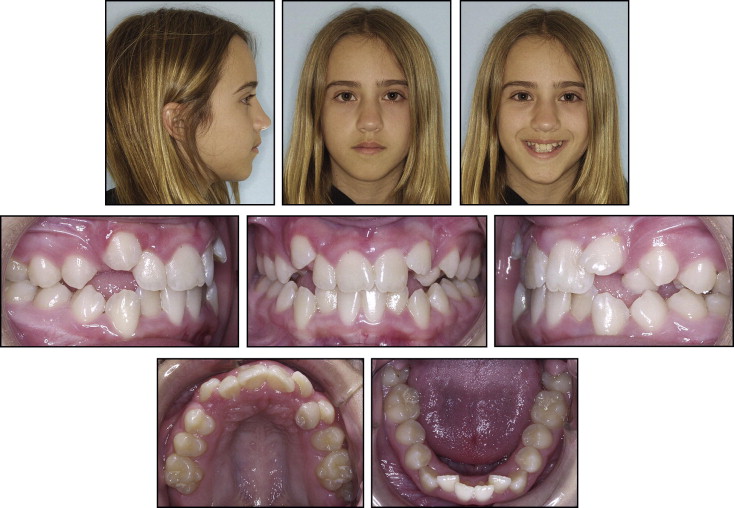

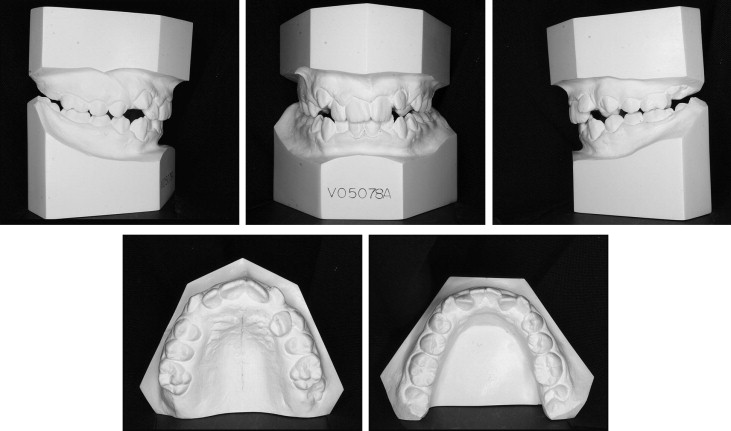

A girl, aged 12 years 5 months, came to my practice with the chief complaint of malaligned teeth ( Figs 1 and 2 ). She was physically healthy with no history of dental trauma. She had a slightly convex profile with mild chin asymmetry to the right. She had a pleasing smile and lip competence. The intraoral examination showed half-cusp Class II molar relationships with crowding of 3.5 mm in the mandibular arch and 9 mm in the maxillary arch. The maxillary left canine was blocked out of the arch, and the maxillary left lateral incisor was proclined labially. The maxillary left canine could not be palpated labially or palatally. Her maxillary dental midline was displaced 2 mm to the left of the facial midline and mandibular dental midline. Overbite was 25% with an exaggerated curve of Spee of 3 mm.

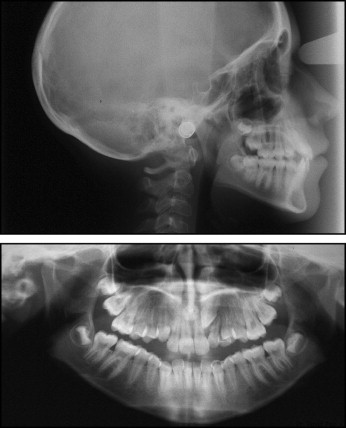

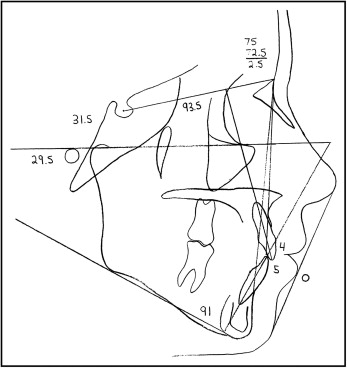

The panoramic radiograph showed normal root and tooth development, with the exception of transposition of the maxillary left canine and the lateral incisor ( Fig 3 ). Cephalometric assessment showed a Class I, mesofacial skeletal pattern (Wits, 1.5 mm; ANB, 2.5°; SN-GoGn, 33°) with normally inclined incisors ( Fig 4 , Table ).

| Pretreatment | Posttreatment | |

|---|---|---|

| SNA | 75° | 76° |

| SNB | 72.5° | 75° |

| ANB | 2.5° | 1° |

| Wits | −1.5 mm | −3 mm |

| SN Go-Gn | 31.5° | 37° |

| FMA | 29.5° | 28° |

| Max 1-NA | 4 mm | 8 mm |

| Max 1-SN | 93.5° | 105° |

| Mand 1-NB | 5 mm | 7 mm |

| Mand 1-Go-Gn | 91° | 96° |

| E-line | 0 mm | −1 mm |

Treatment objectives

Ideally, the treatment objectives would include full resolution of the transposition. However, achievement of this objective might subject the transposed teeth to mechanics that have significant root resorption risks. Class I molar and canine relationships, ideal overjet and overbite, and an esthetic smile with minimal change in the profile were desired.

Treatment objectives

Ideally, the treatment objectives would include full resolution of the transposition. However, achievement of this objective might subject the transposed teeth to mechanics that have significant root resorption risks. Class I molar and canine relationships, ideal overjet and overbite, and an esthetic smile with minimal change in the profile were desired.

Treatment alternatives

The following treatment alternatives were considered and discussed with the patient and her parents.

- 1.

Extraction of 3 first premolars (14, 34, 44) and the transposed canine (23) with intrusion of the maxillary left first premolar (24) to match the gingival height of the contralateral canine. After orthodontic treatment, a veneer would be placed on tooth 24 to match the morphology of the contralateral canine and bring it into occlusion for canine disclusion. Extractions without careful anchorage control could negatively affect her profile.

- 2.

Nonextraction treatment without resolution of the transposition followed by postorthodontic veneers in an attempt to normalize crown morphology and create ideal function. The disadvantage is the unlikelihood of ideal smile esthetics. The advantage is the minimal risk of root interferences during alignment. There is also less chance of bony loss of the buccal cortical plate of the canine, since it does not have to pass labially to the lateral incisor.

- 3.

Extraction of the maxillary left lateral incisor (22), normalization of the canine, and a future implant in the lateral position. This would be considered if, when analyzing the initial records, significant root resorption was found on the lateral incisor. The advantage is a relatively short treatment time. However, the future cost of an implant-supported crown must be considered.

- 4.

Nonextraction treatment with full resolution of the transposition. This plan has been described previously in the literature. One disadvantage of resolving a transposition is the likelihood of a protracted treatment time, as has been demonstrated previously. Another disadvantage is the likelihood of root resorption to the lateral incisor if root interferences are not eliminated during mechanics. Also, there is the potential for loss of the buccal cortical plate on the canine as it passes distally and labially to the lateral incisor. It was explained to the patient’s family that, if the lateral incisor suffered significant root resorption, it would be extracted, the canine would be normalized, and a future implant-supported crown would be placed in the lateral incisor’s position (alternative 3).

All treatment options would achieve an ideal Class I molar relationship and ideal overjet. However, the patient and her parents wished to avoid postorthodontic restorative work if possible and were willing to accept a protracted treatment plan (alternative 4). The risks of root resorption to the lateral incisor and loss of the buccal bony plate on the canine were understood and accepted by the patient.

Treatment progress

The exact relative positions of the transposed teeth were impossible to ascertain on the pretreatment panoramic radiograph. We instead planned on initially leveling the maxillary arch (with no bracket on 22, except for a metal pad to satisfy the patient, who was self-conscious about having a front tooth without a bracket attached). After leveling, we planned to open space for the transposed teeth, followed by more radiographs and, possibly, a cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) scan to better assess the position of the canine relative to the root of the lateral incisor.

Fixed appliances (self-ligating Damon2, 0.022-in slot; Ormco Corporation, Orange, Calif) were placed in the maxillary arch in May 2005. A nickel-titanium (NiTi) open coil was used to gain more space for the transposed teeth. Radiographs taken after the arch was leveled did not clearly show the relative tooth positions ( Fig 5 ); an occlusal image suggested that the canine crown was palatal to the root of the lateral incisor, but the periapical images suggested that the crown of the canine was buccal to the lateral incisor root. A CBCT scan was obtained in December 2005 ( Fig 6 ). The scan and the composite video showed a complete transposition, with the crown of the canine buccal to the root of the lateral incisor, yet palatal to the crown of the lateral incisor (still images, Fig 6 ). Bracket placement and archwire engagement at this time on the lateral incisor would bring the root labially and into the crown of the canine, most likely leading to root resorption. Surgically exposing the canine and pulling it distally would drag the crown of the canine across the cervical junction of the lateral incisor, also a risky proposition. It appeared instead that, if the lateral incisor could be simply tipped palatally, it would create enough space to bring the canine into the arch without engaging the lateral incisor on its way down. A palatal bar was fabricated with soldered hooks; the bar and buttons were placed on the crown of the lateral incisor. The lateral incisor was activated with a power chain ( Fig 7 ). After 6 weeks, a second CBCT scan was taken. It showed complete separation of the lateral incisor root and the canine crown (still images, Fig 8 ). A path had been cleared for surgical exposure and traction of the canine. No root resorption was noted on the lateral incisor.