, Y. Natalie Jeong1, Robert J. Rudy1 and Daniel K. Coleman1

(1)

Department of Periodontology, Tufts University School of Dental Medicine, Boston, MA, USA

6.1 Phasing of Therapy

Patient care should be divided into 4 main phases of therapy, and today’s dental health team needs to be familiar with the components of each phase.

-

Phase I therapy refers to removing and controlling the etiologic factors contributing to dental disease as well as patient education in preventive dentistry techniques. It should be noted that prior to the initiation of phase I therapy, all emergency dental needs must be addressed (Figs. 6.1, 6.2, and 6.3).

Fig. 6.1Inflammatory changes in color, size, and shape of papillary anatomy

Fig. 6.1Inflammatory changes in color, size, and shape of papillary anatomy Fig. 6.2Loss of surface stippling with bleeding on probing

Fig. 6.2Loss of surface stippling with bleeding on probing Fig. 6.3(a) Correct probing—tip of probe should go beyond any calculus deposits and lightly touch the tooth surface and the epithelial attachment simultaneously. (b) Incorrect probing technique—the tip of the probe penetrating into the inflamed soft tissue anatomy—will illicit pain, bleeding, and false probing depths

Fig. 6.3(a) Correct probing—tip of probe should go beyond any calculus deposits and lightly touch the tooth surface and the epithelial attachment simultaneously. (b) Incorrect probing technique—the tip of the probe penetrating into the inflamed soft tissue anatomy—will illicit pain, bleeding, and false probing depths -

Phase II therapy refers to surgical services.

-

Phase III therapy refers to fabrication of permanent dental and prosthetic restorations.

-

Phase IV therapy refers to maintenance therapy services.

6.1.1 Advantages of Phasing Treatment Plans

There are several distinct advantages, to both the dentist and patient, for phasing all treatment plans; they include the following:

1.

Preventive dentistry counseling and services precede reparative dentistry.

2.

Patients can more easily understand complicated treatment plans when the total array of services is segmented into smaller, more limited groups of services.

3.

Phasing ensures that periodontal health is achieved before reparative dentistry is undertaken.

4.

The phase I therapy reevaluation offers the dentist a 2nd opportunity, after initial tissue healing, to adjust the details of the final treatment plan.

5.

Phasing ensures that once periodontal health has been achieved and caries prevention services have been offered, long-term vigilance through a structured maintenance therapy program will minimize the risk of recurrence of disease.

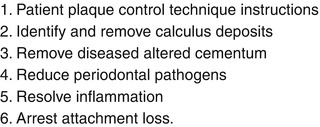

6.1.2 Phase I Therapy (Fig. 6.4)

Fig. 6.4

Six non-surgical periodontal therapy objectives

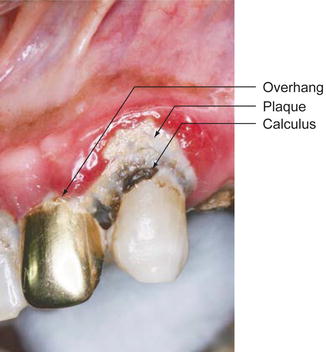

The basic purposes of phase I therapy, also known as active or initial therapy, are to eliminate inflammation by correcting and removing etiologic factors, particularly oral microorganisms, and to educate and motivate patients to take personal responsibility for the care of their dental and periodontal tissues. Many clinicians also include emergency services under initial phase I therapy guidelines (Figs. 6.5, 6.6, 6.7, and 6.8).

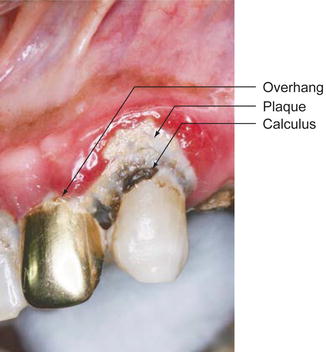

Fig. 6.5

Local irritating factors

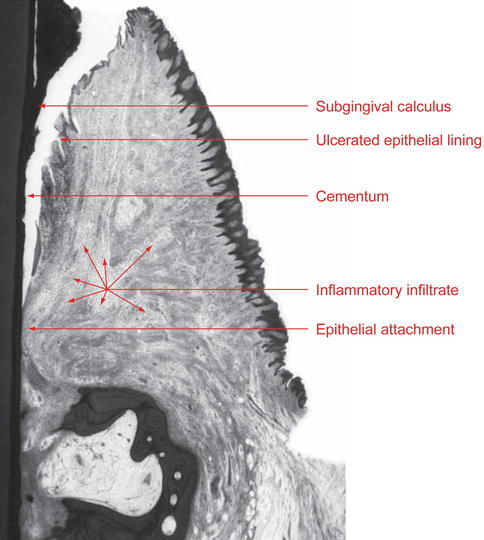

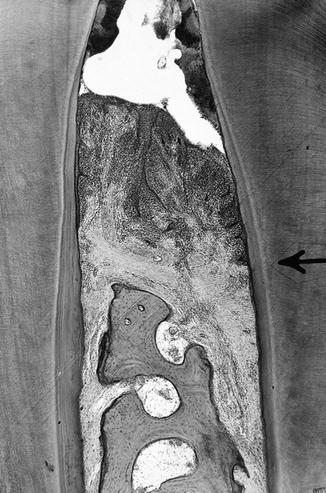

Fig. 6.6

Facial histological appearance

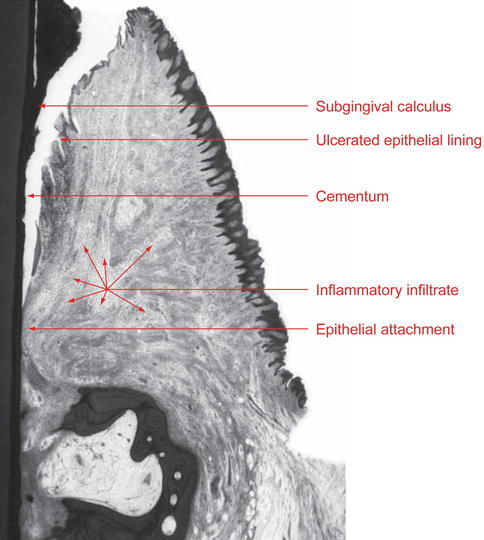

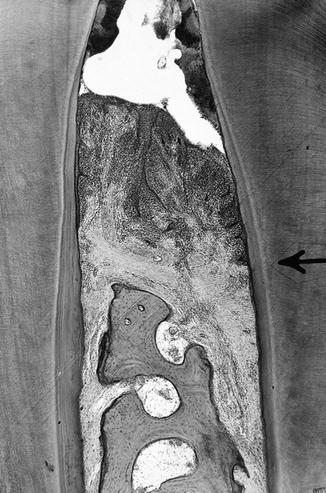

Fig. 6.7

Interdental histological appearance—note calculus deposits, crestal bone loss, attachment loss, and dense cellular inflammatory infiltrate

Fig. 6.8

(a) Compressed air and explorers are used to detect calculus, caries, and defective restorations. (b) Note polished restorations, removal of plaque and healing of the lingual pocket. (c) Note removal of calculus on the root surface; however, due to the persistent deep pocket, there is still the presence of plaque

6.1.2.1 Phase I Therapy Reevaluation: The Key to Clinical Success

Phase I therapy should NOT be considered complete without a formal reevaluation of the results of therapy. The interval between initial therapy and reevaluation may vary depending on the treatment rendered.

Recommended intervals for reevaluation of phase I therapy:

-

For patients with gingivitis who have received a dental prophylaxis, reevaluation occurs 4–6 weeks after treatment.

-

For patients who present with periodontitis and have received scaling and root planing, an 8–10 week reevaluation is recommended.

An adequate passage of time is necessary before the reevaluation appointment is scheduled; this is necessary for the following four reasons:

1.

To allow adequate healing of the gingival and periodontal tissues following the clinician’s mechanical plaque and calculus removal procedures.

2.

To allow patients to weave prevention methods into their daily schedules and routines.

3.

To allow dentists to complete the other very important components of the phase 1 treatment plan such as:

(a)

Caries control

(b)

Extraction of non-treatable teeth

(c)

Endodontic therapy

(d)

Provisionalization of crowns and bridges

(e)

Closure of open contacts

(f)

Removal of restorative overhangs

(g)

Occlusal adjustments

(h)

Fabrication of occlusal night guards

(i)

Specialty consultations (Figs. 6.8, 6.9, 6.10, and 6.11).

Fig. 6.9

(a, b) Provizationalization achieves not only dentinal coverage but allows for improvement in embrasure form, esthetics, and occlusal relation. These improvements will allow the gingival tissues and periodontal ligaments an opportunity to heal

Fig. 6.10

(a, b) Reduction of bulky restorative material

Fig. 6.11

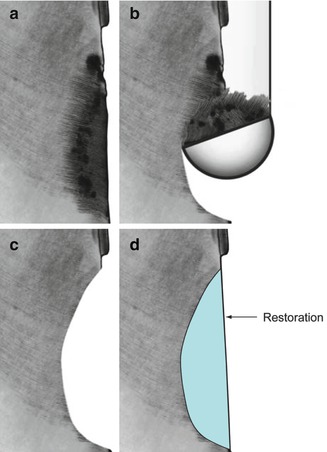

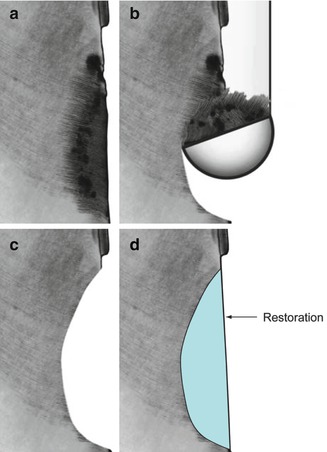

(a–d) Root caries removal and placement of a final restoration

4.

To allow for additional sessions that will focus on reviewing plaque control measures and motivational counseling regarding the advantages of preventive dentistry. These additional short sessions can easily be added as 5–15 min “stand-alone” appointments or be incorporated with the other phase I therapy services, as mentioned previously.

Clinical criteria that document achievement successful results of phase I therapy:

-

No erythematous gingiva present

-

No enlargement of the gingival margins or gingival papillae

-

No bleeding from the gingival sulcus upon gentle probing

-

Reduction in pocket depths

-

Tooth surfaces are smooth and hard, free from supra- and subgingival calculus, disease-altered cementum and supragingival stain.

-

Reduced tooth mobility patterns

-

Cervical clinical crown contours free of restorative overhangs and excessive bulkiness

-

All open contacts closed with temporary restorations

-

Plaque-free score of 85 % or higher: Patient can demonstrate correct plaque removal procedures using brushes, floss, and rubber tip; patient is spending 5–10 min per day, with home-care measures (Fig. 6.12).

Fig. 6.12(a) Note lingual gingival inflammation prior to treatment. (b) Note reduction in inflammation subsequent to polishing of rough amalgam restoration, scaling, and improved patient plaque control

Fig. 6.12(a) Note lingual gingival inflammation prior to treatment. (b) Note reduction in inflammation subsequent to polishing of rough amalgam restoration, scaling, and improved patient plaque control

6.1.2.2 The Six-Step Protocol for Phase I Therapy Reevaluation

After a complete periodontal charting has been recorded, the clinician must:

1.

State the original diagnosis.

2.

State the treatment rendered—make a brief summary of the patient’s progress to date.

3.

Comment on the patient’s ability to control plaque.

4.

State today’s gingival and periodontal diagnosis—compare with original diagnosis before treatment and determine if clinical health has been achieved or not; if not, determine the etiology.

5.

Determine if there has been resolution of the patient’s chief complaint, whether of a physical or emotional nature.

6.

Outline additional therapy required to achieve complete health.

There are four possible decisions that can be arrived at following the phase I therapy reevaluation appointment, which should be made by the treating clinicians.

1.

Refine phase I therapy.

2.

Proceed with phase II periodontal surgical services.

3.

Commence with phase III restorative therapy if no further active periodontal therapy is needed.

4.

Refer clinically healthy patients to the maintenance therapy program (phase IV therapy).

It is critically important at this juncture in the management of patients with an original diagnosis of periodontal disease that the person performing the phase I therapy reevaluation be very familiar with the common indications for periodontal surgical services. General dentists and hygienists must learn to realize that in spite of many successful cases based on phase I services alone, there are profound limitations for many patients as to what can be achieved clinically, even if phase I therapy is repeated and refined numerous times.

Periodontal surgical services, as a group, have great potential to benefit the oral health of many of our patients. Failure to review surgical options and alternatives deprives many patients of the opportunity to achieve the highest standard of oral health. Surgical periodontal services serve to compliment phase I, nonsurgical therapy, not to replace them. These services have an integral role to play in enhancing the standard of oral health for our patients.

6.1.3 Phase II Therapy

Surgical intervention including periodontal surgery and nonemergent exodontia are included in phase II therapy.

6.1.3.1 Common Clinical Indications for Periodontal Surgical Services

-

Augmentation of missing or narrow zones of keratinized attached gingiva

-

Release of high frenal attachments which create tension at the gingival margins

-

Coverage of exposed root surfaces

-

Deepening of shallow vestibular anatomy

-

Gingival pocket elimination (resective methods)

-

Periodontal pocket elimination (resective or regenerative methods)

-

Crown lengthening surgery for functional or aesthetic purposes (hard and soft tissue resection)

-

Pre-prosthetic edentulous ridge augmentation (hard and soft tissue grafting)

-

Removal of amalgam tattoos

-

Correction of bulky gingival contours with gingivoplasty

-

Implant site preparation procedures:(a)Guided bone regeneration (GBR) of previously healed extraction sites(b)GBR of new extraction sites (also called ridge preservation)(c)Sinus elevations with bone grafting

6.1.4 Phase III Therapy

This is the restorative phase of treatment and includes operative dentistry, fixed restorations, removable prosthesis, and orthodontics.

6.1.5 Phase IV Therapy

(see Chap. 8)

6.2 Clinical Treatment

6.2.1 The Rationale for Dental Prophylaxis and Scaling and Root Planing Procedures

There are three basic therapeutic techniques that have evolved and have been successfully employed by periodontal specialists, dentists, and hygienists, in their efforts to treat gingival and periodontal infections—infections so ubiquitous that they have been currently reported to affect over 50 % of the US population. It is the mastery of these techniques, scaling, and root planing with coincidental soft tissue curettage that enables today’s clinicians to be of truly great service to their patients, who commonly display various stages of gingivitis and periodontitis.

The appropriate selection and skillful delivery of these basic procedures, in conjunction with therapeutic plaque control measures at home by the patient, offers all patients several distinct advantages:

(a)

Arrests the progress of the diseases gingivitis and periodontitis

(b)

Reduces probing depths subsequent to pocket wall shrinkage

(c)

Reduces probing depths subsequent to reattachment and regeneration of the healing tissues

(d)

Reduces or eliminate entirely bleeding from the gingival tissues

(e)

Facilitates plaque control by the patient

(f)

Provides tissue conditioning if periodontal surgery is being considered

(g)

Results in healing and a return to clinical gingival and periodontal health in many cases, obviating the need for further surgical considerations, as well as improving the patient’s general health

6.2.2 Scaling

Over the centuries, many physicians and dentists have advocated the therapeutic value of scaling to reduce gingival inflammation. Among the most notable were Albucasis, Pierre Fauchard, Leonard Koecker, John M. Riggs, and Greene Vardiman (GV) Black.

During the last 100 years, the basic instruments and techniques that evolved by the end of the nineteenth century have been further refined, and the clinician can now choose from a great variety of instrument designs. The subject of scaling, which received minimal attention in dental school curriculums prior to 1939, is now routinely taught in all hygiene and dental programs.

The scaling procedure, often termed a “cleaning” by the patient, refers to the careful and thorough removal of plaque, calculus and stain from the exposed surfaces of the teeth upon which they have accumulated. Scalers, curettes, and ultrasonic instruments are used on enamel surfaces in order to dislodge these accumulations.

The rounded ends (toes) of curette blades are adapted to the convex and concave cemental root surfaces and can remove calculus deposits without gauging the root surface. A thorough study of root anatomy will enable the clinician to instrument the root surface contours efficiently and with minimal risk of injury, both to the root surface itself and to the adjacent soft dentogingival tissues.

Scalers are not routinely used to scale cemental surfaces because the sharp tips of these instruments can create gauging of the root surface and tearing of the adjacent soft tissues if placed subgingivally. The sharp point of a scaler is meant to be used supragingivally or just below the contact area.

The terms, supragingival scaling versus subgingival scaling, refer to the location of the scaling procedure whether the procedure is carried out occlusal to the gingival margin versus apical to the gingival margin.

Calculus attaches to the tooth through the following mechanisms:

1.

Direct attachment of calculus matrix to tooth surface. This is the most frequent mode of attachment of calculus on cementum.

2.

Cuticular attachment—a secondary cuticle is interposed between the calculus and tooth surface. This is the most frequent mode of attachment of calculus on enamel.

3.

Mechanical attachment of calculus into undercuts. The undercuts may be the result of resorption, caries, or grooves from previous instrumentation.

4.

Intercrystalline bonding between hydroxyapatite crystals of calculus and cementum.

“The variety of attachment mechanisms for subgingival calculus results in deposits that are often very difficult to remove from the root surface.”—Dr. Irwin D. Mandel (1987)

Calculus detection involves visual inspection of clinical crowns that have been dried using compressed air, in combination with tactile information derived from correct and sensitive subgingival usage of dental explorers. Detection of subgingival roughness should prompt the clinician to consider the presence of calculus, caries, or restorative overhangs. Following the removal of calculus from enamel or cemental surfaces—the surface should feel hard and “glassy” smooth.

The proper removal of calculus entails the use of thoroughly sharpened scalers or curettes; these instruments must be carefully inserted apical to the calculus deposit, and the face of the blade must be oriented to the tooth surface in a 70–80° range of angulation. Only this angulation will allow the previously sharpened blade edge to be effective in detaching the calculus deposit as the instrument is activated with appropriate firm lateral pressure, in a horizontal, oblique, or vertical direction. The scaling procedure should not be a painful procedure for the patient, and the appropriate use of topical and local anesthetic should be expected and gently administered. Once the clinician thinks all calculus deposits have been removed, a careful reassessment with compressed air and subgingival exploration with an explorer needs to be undertaken. It is the constant challenge to find, to remove, and to double-check one’s own work that allows the disciplined clinician to develop the very necessary tactile sensitivity skills that will benefit the patient (Figs. 6.13, 6.14, 6.15, 6.16, and 6.17

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses