Over the years, many articles have appeared in the AJO-DO regarding public relations and image. These have included discussions of the many “publics” that are involved, including our relationships with the public in general, other specialties of dentistry, and general dentists. Some of these discussions were centered on images that are formulated in the office (personal appearance, actions, and attitudes of doctors and staff; office layout and décor; Web site content and appearance), whereas others addressed the value of involvement in professional organizations and community, civic, and social activities. This editorial will focus on our image and relationships with the general public and within dentistry, and to a certain extent, it will echo ideas and issues that have been discussed before. In doing so, I admit that this editorial was hard to write, and I suspect it will be hard to read. So, as my dentist used to say: “sit back and relax; this might hurt a little.”

During the early days of the specialty and the American Association of Orthodontists, orthodontists were generally admired for their concern about children’s health and welfare; the goal at the time was to work toward a day when treatment was available to every child who needed orthodontic care. Individual efforts were eventually replaced by a centralized public relations initiative that began in earnest in the 1930s and aimed to educate, guide, and protect the public. At that time, there was great interest in providing such information to the public via magazine articles and leaflets that were written for specific audiences who were to “spread the good word about orthodontics” without the perception of self-promotion (ie, they were not provided to practitioners to hand out). This included targeting those involved in health care (physicians, dentists, dental hygienists, child psychologists), those involved in public health activities (health officers, public health nurses, nutritionists, health association volunteers, public health students, nursing schools), and those associated with the public school system (school administrators, school nurses, health teachers, parent-teacher associations, women’s clubs, and vocational advisors).

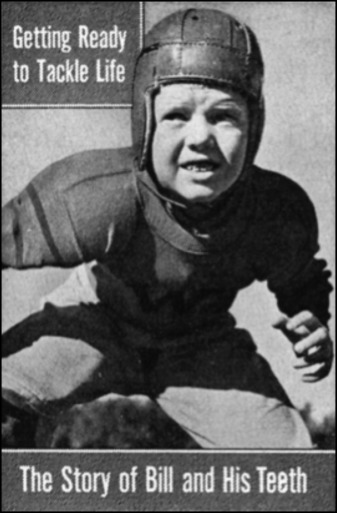

One early positive and productive effort was a pamphlet subtitled “The Story of Bill and His Teeth.” It told of a young lad who had a disappointment in football but whose life and attitude were later greatly improved because of orthodontic treatment ( Fig ). Another popular pamphlet, “Facts About Orthodontics for Health Workers,” was widely disseminated. Magazine articles touted the benefits of orthodontics, and radio shows did the same. Orthodontists also became active in support of other common causes, notably the use of fluoride to control caries. Overall, orthodontists were admired and respected as professionals. They instilled public confidence, and they were considered caring, responsible, courteous, and honest.

Over time, other opportunities for “spreading the word” became available and useful, including outdoor advertising (signs and billboards), telephone directories, newspaper articles and advertisements, television, and, lately, the Internet. In this new world, one might wonder whether the relationship between the public and orthodontics has improved, stayed the same, or declined. Perhaps part of the answer can be determined by evaluating 2 articles that appeared in February 2015 in the New York Times : “Straighter Teeth by Mail” and “Do-It-Yourself Orthodonture: Don’t Try This at Home.” These articles intended to inform, guide, and protect the public; although the message was a little twisted in the reporting, the articles accomplished what was intended. Even more important to this editorial were the 200 or so online comments posted by readers. Some were informed and supportive of orthodontics and orthodontists, but others were critical. The negative comments suggested that orthodontics is expensive and uncomfortable and takes a long time, with much of the work done by assistants (not the doctor), and bad outcomes can happen (root resorption, relapse, devitalization, and so on). The words chosen to emphasize negative feelings were difficult to read: corrupt, monopoly, racket, thieves, dishonest, elitists, money grubbers, fear-mongers, price-fixers, mafia, sleazy, incompetent, and others … often in an “us vs them” type of argument. This was shocking.

Of course, one could be defensive and dismissive of the comments, but there seems to be a message that might be worthwhile to consider. In terms of public relations, there is much work yet to be done. It is clear that some of the public knows about, appreciates, and respects orthodontics, but a significant part of the public knows very little about orthodontics, and so they miss the messages that we think are important, and they might not trust us as we would like them to. To us, orthodontics is not mysterious, but apparently it is to a significant segment of the public. Ironically, because of information made available to the public via television, the average person appears to have reasonable baseline knowledge about some complex maladies such as cancer, tuberculosis, Ebola, and others, and some knowledge about complex drugs used in the treatment of conditions such as depression, heart disease, rheumatoid arthritis, and erectile dysfunction. Even so, they do not seem to know about or understand something simpler: orthodontics. Based on this, I would argue that the public needs much more information about orthodontics. Before we can convince people that they should accept a certain idea or follow a specific course of action, they need good basic information about orthodontics.

As to how to best cast our image in the future, that will be collectively determined by the American Association of Orthodontists, its constituents and components, and individual orthodontists. The latter are most important, since we not only work for ourselves but also for the betterment of all of our other colleagues … all in service to patients.

Now, one might like general practitioners and other specialists to help us in this public relations endeavor. However, it is likely that the attitudes of other members of the dental profession might be contributing to this lack of knowledge by the public. As an example, in 1931, C. V. Mosby recounted a story about Edward H. Angle.

The first time I ever heard the word ‘orthodontics’ spoken was in St. Louis more than twenty-five years ago when a dentist remarked to me that Doctor Angle was the biggest grafter he had heard of because he had just charged $1500.00 ∗

∗ The average income in the United States at the time was approximately $500 per year.

for straightening the teeth of a child of the X___ family (one of the wealthiest families in St. Louis). This was my introduction to orthodontics and it was given by a dentist.

It can also be argued that over the last 100 years, the education provided to dental students about orthodontics has generally been poor. As a result, it should not be surprising that many dental graduates have been indifferent and do not feel inclined to tell patients much about orthodontics, let alone praise its benefits. Many dentists have also been inappropriately critical of orthodontics, suspicious of orthodontists, and antagonistic toward the specialty. They have suggested that orthodontists are looking for the rich patients from whom they can receive the largest fees. Orthodontists have been characterized as aristocrats, entitled, impersonal, unsympathetic, and hard to reach. Perhaps such attitudes initiated the derogatory term “wire bender.” At a minimum, it can be concluded that we have been badly misunderstood and poorly characterized over time.

Dentists should be the bearers of good tidings to the public about orthodontics; some do that, but others do not. Some even suggest that the health and welfare of the child and adolescent can be compromised by orthodontics. This situation has also fostered great misconceptions about orthodontics and contemporary treatment. As a result, many dentists stand as a barrier to the understanding of orthodontics by the public.

It can also be argued that orthodontists have not made continuous, well-directed efforts to be supportive of dentistry. As a case in point, look at the number orthodontists who have been elected to serve as president of the American Dental Association. In the 1930s, 2 orthodontists served as its president; 2 more were elected in the 1940s; and 2 more in each of the next 3 decades. In the 1980s, 1 orthodontist was selected, and then none over the next quarter century. Is there a message here?

Furthermore, according to the most recent orthodontic practice survey published in the Journal of Clinical Orthodontics in 2013, 100% of orthodontic practices received patient referrals from general practitioners. In 2003, the median percentage of patients treated by an orthodontist and referred by general practitioners stood at 50%; this declined to 40% in 2011, and in 2013 the percentage declined even further to 35%. Is there a message here?

From my view, we are still being supported by dentists and dentistry, but we must seek ways to work with our dental colleagues more in the future than we have done in the past. There is no value in being isolated in terms of the advancement of the specialty of orthodontics and the quality of care that patients receive. Moreover, improving our interaction with our dental colleagues would be an extension of the vision of Vincent Kokich, who spent much of his professional life extolling the virtues of interdisciplinary care and its related demonstration of the mutual dedication of practitioners to improvements in patient care.

Now, one could argue that this is a small problem rather a large one, but that dismissal misses the point; no matter the size of the problem, it is still a problem that will take positive effort to produce needed improvement. Public relations that are bad in singular or small ways can overshadow all your other individual good works, and all the good works of others by association. Furthermore, not much will come from practitioners and members of the public who are sour about everything and seek to be defined by what they oppose rather than by what they support; they are lost. Over time, we have treated millions of patients to a good end, and this has served us well as preparation for a better tomorrow for the specialty and the millions more who will be served in the future. Public relations are a manifestation of the contemporary values of the specialty and its parent organization as they interact with the changing needs and desires of the public. So, there is always need for assessment and always room for improvement. It thus seems that it is the right time to call for personal reconsideration of our image and seek actions that will improve our relationships with others as we strive for the greater good of the many, rather than the vested interests of a few.

Rolf G. Behrents

“Follow impulses and leaderships that represent ideals; that point the way to your professional destiny; that express—in integrity, fidelity, service, and lofty purposes—the finest that is in you individually and professionally.” If you proceed along this route, your specialty will continue to deserve the highest professional esteem and the greatest public appreciation.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses