Esthetic stigmata and functional impairments associated with craniofacial and maxillofacial deformities have long challenged surgeons in the management of deficiencies of the middle third of the face. The French anatomist Rene Le Fort published in 1901 his classic treatise on the description of common fracture patterns in the middle facial third. The ensuing World Wars produced horrendous mass casualties that steered facial reconstructive surgeons like Kazanjian in their efforts to manage injuries of the middle third of the face. Building on the knowledge and skill borne by these conflicts, Sir Harold Gillies was the first surgeon to publish an attempt at mobilization of the midface in the treatment of a patient with craniofacial dysostosis. This procedure was unsuccessful and was abandoned by Gillies. Subsequently, Longacre attempted reconstruction of the midface in patients undergoing craniosynostosis by autogenous rib grafting. This procedure did nothing to address the functional impairments associated with total midface deficiency; furthermore, resorption of the grafts occurred. The long-term stability of reconstruction from an esthetic standpoint was questionable. In 1967, the pioneering efforts of Tessier revolutionized treatment of the patient with total midface deficiency. These landmark presentations and publications describing mobilization of the entire middle face through the concept of a combined intracranial and extracranial approach in a safe and consistent manner was groundbreaking. Modifications and extensions of this concept by Tessier and others have resulted in surgical techniques that provide relief of functional impairment and facial esthetics that benefit the patient with severe midface deficiency. The first known performance of this surgery in the United States was undertaken by Dr. Robert V. Walker in 1967, shortly after Tessier’s presentation in Rome.

INDICATIONS

Skeletal facial deformities can be repetitive patterns of deformity that affect the different functional and esthetic subunits of facial hard and soft tissues. Their only common feature is the degree of variable expressivity within each subtype of anomaly. Although numerous procedures can be done for the management of various craniofacial malformations in the middle third of the facial skeleton, only the subcranial Le Fort III osteotomy treats the nose, orbits, cheeks, and maxilla. However, specific limitations apply to the use of this surgical maneuver. The bony structures of the middle facial third are in contiguity with the cranial base superiorly. Transgression of this natural barrier is indicated in the surgical correction of some craniofacial anomalies when the presenting deformity includes excessive interorbital distance, or when significant aberration of the supraorbital/forehead subunit is apparent. In these instances, consideration should be given to using a combined intracranial and extracranial approach, such as facial bipartition or monobloc osteotomy. In addition, the subcranial Le Fort III osteotomy does not correct three-dimensional vertical slanting of the facial halves or the convex arc of rotation of the face, as may be seen in some patients with craniofacial dysostosis that can be adequately managed only with facial bipartition osteotomy.

This is not to suggest that within the context of an extracranial procedure, the Le Fort III osteotomy is inflexible; rather, the opposite is true. Modifications of the Le Fort III osteotomy, such as Kufner’s operation (modified Le Fort III), are possible and can be used to correct deformities that do not involve the nasal subunit. The stability of these procedures in both syndromic and non-syndromic patients has been studied. Thoughtful consideration by the surgeon must be given to addressing the presenting dysmorphology, with the intention of improving the patient’s esthetic and functional problems, while taking into account the potential complications and benefits associated with the use of an intracranial approach. Treatment of the skeletally immature patient requires surgical intervention that is based on the complex balance between long-term stability of the correction and the more immediate functional, psychological, and esthetic demands of each patient. As with all facial reconstructive procedures, patient selection is critical for a successful outcome.

CRANIOFACIAL DYSOSTOSIS

Craniofacial dysostosis syndromes (e.g., Apert, Crouzon, Pfeiffer, Saethre-Chotzen, Carpenter) are characterized by sutural involvement that not only includes the cranial vault but extends into the skull base and the midfacial skeletal structures. Although the cranial vault and the cranial base are thought to be the regions of primary involvement, a significant impact on midfacial growth and development has been noted. In addition to cranial vault dysmorphology, patients with these inherited conditions exhibit a characteristic “total midface” deficiency that must be addressed as part of the staged reconstructive approach. Although similarity has been reported between the patterns of facial growth and development in these patients, a high degree of variable expressivity is seen in each patient, regardless of syndrome. This must be taken into account during planning and execution of surgical correction of these deformities. If the nasal subunit is normal or is excessive preoperatively, further advancement of the nose will lead to a less than esthetic result. Therefore, the surgeon must give consideration to subtotal midface advancement via modified Le Fort III osteotomy.

CRANIOFACIAL DYSOSTOSIS

Craniofacial dysostosis syndromes (e.g., Apert, Crouzon, Pfeiffer, Saethre-Chotzen, Carpenter) are characterized by sutural involvement that not only includes the cranial vault but extends into the skull base and the midfacial skeletal structures. Although the cranial vault and the cranial base are thought to be the regions of primary involvement, a significant impact on midfacial growth and development has been noted. In addition to cranial vault dysmorphology, patients with these inherited conditions exhibit a characteristic “total midface” deficiency that must be addressed as part of the staged reconstructive approach. Although similarity has been reported between the patterns of facial growth and development in these patients, a high degree of variable expressivity is seen in each patient, regardless of syndrome. This must be taken into account during planning and execution of surgical correction of these deformities. If the nasal subunit is normal or is excessive preoperatively, further advancement of the nose will lead to a less than esthetic result. Therefore, the surgeon must give consideration to subtotal midface advancement via modified Le Fort III osteotomy.

MIDFACE DEFICIENCY

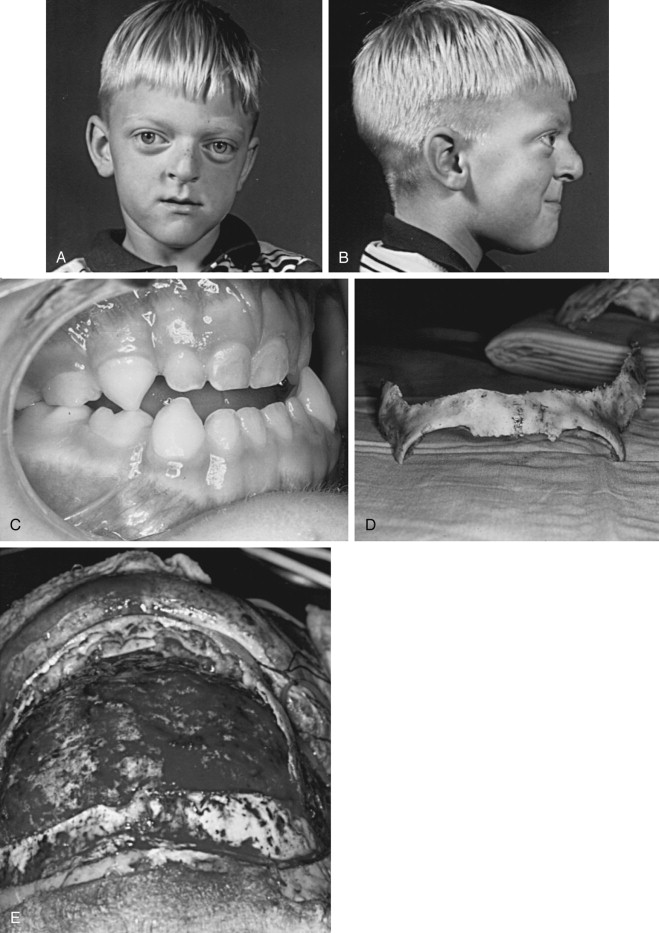

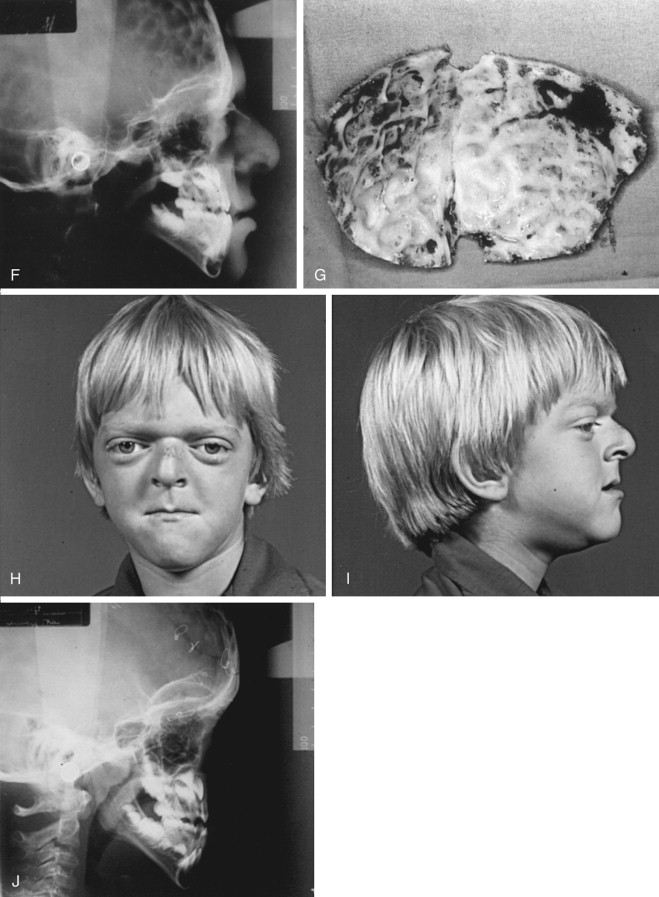

The role of the human face is significant in a direct and an indirect fashion for reasons other than purely esthetic considerations. This is so because of the highly evolved and specialized functions of the face that are involved in vision, breathing, speech production, smell, and hearing, to name a few. Total midface deficiency involving the orbits, nose, zygomas, and maxilla can occur in both syndromic and non-syndromic individuals. In patients with syndromal craniofacial dysostosis, in addition to potential neurologic deficits, variable fusion of the lesser sutures of the skull base is often seen. This commonly results in abnormal ophthalmologic findings such as exorbitism, exotropia, orbital dystopia, and ptosis caused by lack of orbital depth and diameter, as well as prolapse of the ethmoid sinuses through the medial orbital walls. Severe occlusal discrepancies seen in this group of patients are characterized by generalized hypoplasia of the maxilla, transverse deficiency, class III malocclusion, and apertognathia. All of these abnormalities may combine to affect speech articulation and mastication. In addition, cleft palate, when present, can produce velopharyngeal incompetence. The severe retrusive position of the midface can also interfere with nasal breathing and may produce chronic nasal obstruction. Varying degrees of orbital hypertelorism (OHT) may or may not be present. The extent to which this disorder is present strongly influences the type of surgical correction required for midface deficiency ( Figure 9-1, A through E ).

The presence of midface deficiency does not mitigate the co-existence of other facial skeletal abnormalities such as mandibular excess and retrogenia. In addition, irregularities of the forehead often occur, as well as frontal bossing. Nasal length can be short, and projection may be deficient. However, in many circumstances, nasal projection is normal or even excessive; this situation mandates subtotal midface advancement. Deficiency in orbital depth and diameter produces exorbitism, and an excessive amount of sclera may be present. Ptosis of the lids and lateral canthal dystopia are usually present. When high levels of midface deficiency are seen, the subcranial Le Fort III osteotomy or a modification thereof should be considered ( Figure 9-1, F through J ).

TECHNIQUE

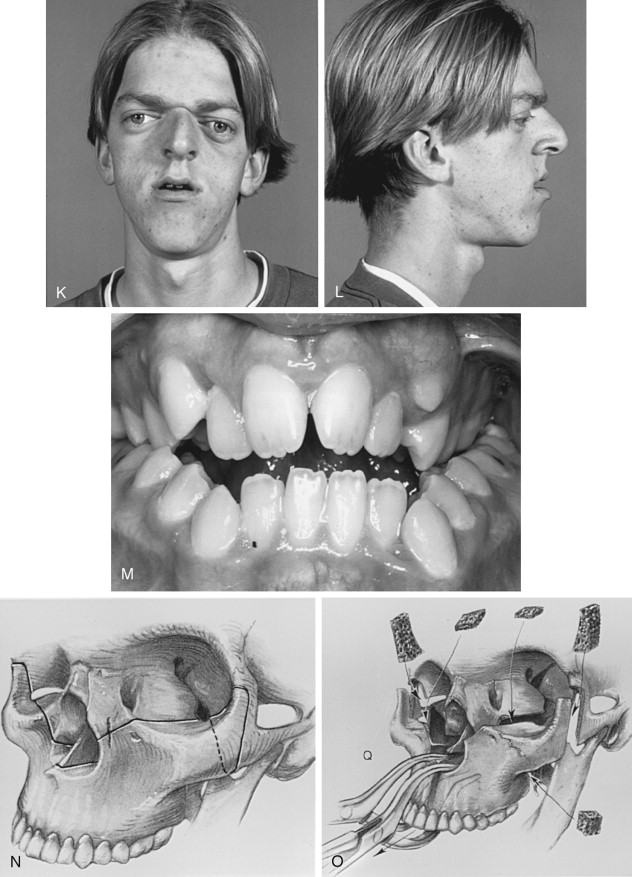

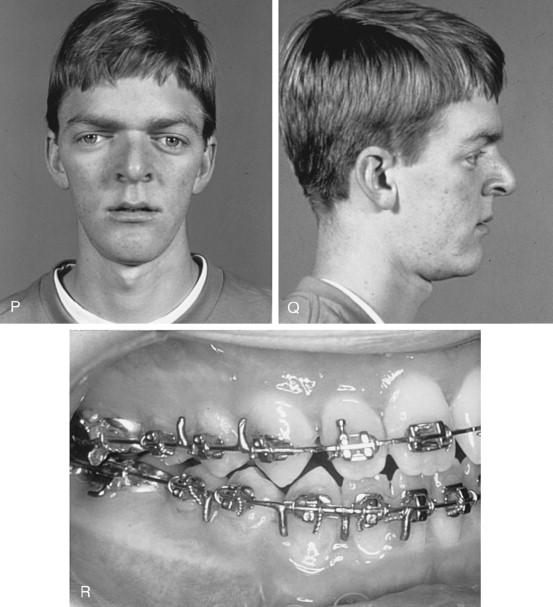

Naso-endotracheal intubation with a reinforced tube that exits inferiorly and across the cheek is preferred. The tube is secured with suture to the membranous septum and columella. Because intermaxillary fixation is necessary to establish the projection of the middle face, oral intubation is less desirable and should be avoided unless the splint can be modified to accommodate the position of the tube. Most of the endotracheal tube must be sufficiently below the level of the vocal cords, to prevent unintended dislodgement during midface disimpaction and advancement ( Figure 9-1, K through M ).

A corneal shield may be used to secure the eyelids after ophthalmologic lubricant is placed. An alternative is to place tarsorrhaphy sutures bilaterally. The hair is protected from the field by draping. The incision line is infiltrated with 2% lidocaine with 1 : 100,000 epinephrine for control of bleeding during dissection in the maxillary vestibular area and in the region of the lower eyelid incisions. The face and the oral cavity then are prepared with Betadine scrub. The entire operative field is straight, thus exposing the oral cavity, eyes, ears, forehead, and scalp posterior to the planned incision (if the coronal approach is used).

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses