This group of diseases is classified broadly under the terms vesiculobullous or vesiculoulcerative disorders. The group includes causes from a number of often unrelated problems including: infectious diseases, genetic diseases, acquired diseases, and idiopathic and autoimmune diseases. Clinically, they generally produce some discomfort to the patient with variability in duration and severity. However, some foundation therapeutic paradigms apply to all these diseases regardless of cause. In addition, some of these diseases are managed rather than cured. Thus control of low-level disease processes is often a key to long-term patient care. In our clinical oral and maxillofacial pathology referral practice, it is not uncommon for many of our referrals to have been treated with the appropriate medications, but the referring clinician did not consider overall maintenance of an intact oral mucosal surface along with the salivary pellicle. Additionally, simple education of the patient of the expected disease course and prognosis is often essential.

These foundation principles, which are discussed later, are not therapeutic in and of themselves. It is best to think of them as providing the best scenario for therapeutic regimens to be most effective. The desired effect is that less potent medications, less complicated regimens, and time between exacerbations may be favorably altered.

- •

Decrease all possible irritants

- •

Avoid mucosal irritants (e.g., pyrophosphates, cinnamon, menthols, phenols, etc.)

- •

Prevent destruction of “salivary pellicle”

- •

Especially prevent sodium lauryl sulfate

- •

Also minimize ethanol

- •

Maintain and build salivary pellicle

- •

Counteract xerostomic agents as much as possible

- •

Hydration

- •

Prescribe cholinergics or buffered citrate

- •

Manage “bugs”

Oral health care products are notorious for having possible irritants incorporated right into the product. Pyrophosphates may be one of the more common irritants in mouth rinses and toothpastes. They are actually seen in the majority of toothpastes. Pyrophosphates act several ways, including to help potentiate the sodium lauryl sulfate and to decrease the possibility of mineralization. When considering irritated oral mucosa, they cannot be considered helpful. In addition, pyrophosphates are not very pleasant tasting, so they are generally masked with the use of cinnamic aldehyde or other strong flavoring agents. Cinnamic aldehyde in particular creates sensitivity reactions in large numbers of patients. In the mouth rinse category, menthol and camphors are not uncommon ingredients. These essential oils all have some antibacterial effect, but also act as an irritant.

Maintenance of the salivary pellicle is one of the most essential aspects of protecting the mucosa. The salivary pellicle is the first defense to prevent antigenic presentation to the immune system. In addition, the salivary pellicle acts as a deflector for minor trauma secondary to mastication habits and oral health care. Sodium lauryl sulfate removes the salivary pellicle very efficiently. Sodium lauryl sulfate is in a number of oral health care products and, most notably, in every toothpaste that foams. Once removed, the patient’s saliva must re-form the salivary pellicle each time. In a normal patient, this is not a major complication, but in the patient with some sort of mucositis, it is best to have the mucosa protected as much and as long as possible. Ethanol also removes the salivary pellicle to a certain extent. Therefore minimization of ethanol-containing mouthwashes is also desirable.

In a number of patients, xerostomia is what minimizes the effectiveness and production of the salivary pellicle. This is usually a result of the multiple medicines that the patient is taking. Xerostomic medications include antidepressants, antianxiety agents, antihypertensives, and antihistamines, just to name a few. All are drying agents. If the patient is taking no type of medication (such as a beta blocker), you may be able to stimulate salivary flow with medications, such as pilocarpine or cevimeline. However, it is very common to have some sort of anticholinergic agent in the patient’s history. For these patients, the only solution may be buffered citrate tablets, which are sold under the brand name of SalivaSure. An even simpler and more basic solution is to instruct the patient on proper hydration.

Good oral hygiene is also very important. For this I tend to think of oral hygiene as managing the “bugs.” I often use alcohol-free chlorhexidine or 2% zinc chloride mouth rinses. Generally, I simply encourage good plaque control through the proper brushing of teeth and actually instruct them to avoid commercial mouthwashes. Often the patient’s mucosal surfaces adjacent to the teeth are very tender and make it difficult to properly brush. I have found that patients are often able to better manage a sonic type of toothbrush to minimize trauma and maximize oral health. Although there is certainly movement associated with the sonic toothbrushes, I find these somewhat better than the shearing action that can occur with many of the rotary type of electric toothbrushes. Manual toothbrushes are often just too difficult to control and always traumatize the adjacent mucosa.

A special note: When treatment is discussed in the various disease categories to follow, the reader will note the absence of some regimens with which they may be familiar. Specifically, concoctions known variously as magic mouth rinse, special mouth rinse, or miracle mouth rinse will not be recommended. A quick note for why this is omitted follows.

Many clinicians have used such rinses, perhaps even successfully. However, in my experience on numerous referrals, there is usually no place for such medication concoctions. The typical formulations for these prescriptions are as follows:

- •

Magic rinse, special rinse, and miracle rinse (all generally the same thing, may be known by other names regionally)

- •

Ingredients

- •

Nystatin 12,500 units/mL

- •

Diphenhydramine 1.25 mg/mL

- •

Hydrocortisone 0.25 mg/mL

- •

Normal nystatin 100,000 units/mL

-

Magic mouthwash 12,500 units/mL

-

This represents an eightfold decrease in potency

-

Even infant thrush treated with 100,000 units/mL

-

- •

Benadryl commonly 25 mg/ml

-

7.5 mg total dose of fairly low concentration too

-

Probably acts as a topical anesthetic, NOT as an antihistamine.

-

For anesthetic effect higher concentration is important

-

- •

Hydrocortisone 25 mg/mL

-

This is a very low potency

-

It is a ten-fold decrease from dexamethasone 0.5 mg/5 mL

-

It is a twenty-fold decrease from 0.1% triamcinolone acetonide

-

- •

Please note these concentrations as outlined above. These concentrations simply do not make any sense. If you think the patient needs steroids, use a potent enough steroid to do the work. If the patient needs an antifungal, why go with a concentration of an antifungal that is eight times less than the mildest antifungal that we would ever prescribe? If we want a topical anesthetic effect, why would we choose diphenhydramine? If we want to use diphenhydramine, why would we not just use it by itself in a more potent concentration or use viscous lidocaine if the patient is old enough? In short, if you believe antifungals are needed, prescribe a proper antifungal. If you think they need an antiinflammatory, prescribe a potent enough steroid to do the job. If they need some topical anesthetic, think about the potency of a topical anesthetic that would be appropriate for the age group being treated.

When steroid rinses are employed or systemic steroids are used, candidal overgrowth is a common complication. In practice, I find it generally useful to give a warning to the patient about the possibility of candidal overgrowth and to alert them to what to expect. But I do not empirically start antifungals on every patient. I generally give a patient a handout to cover this possibility. Anecdotally, the candidal overgrowth probably only occurs in 25% to 40% of the patients, and therefore antifungals are not necessary in the majority of patients. With that said, I have no problem with the preference of some clinicians to go ahead and use adjunctive antifungal therapy when employing steroids.

HERPES SIMPLEX VIRUS INFECTIONS

The herpes family is a family of DNA viruses. The family includes a diverse group of viruses, ranging from herpes simplex 1 through herpes type 8. Diseases caused by or associated with the herpes family include but are not limited to chickenpox, shingles, genital herpes, “cold sores,” chronic fatigue syndrome, Kaposi sarcoma, and mononucleosis. For this discussion, though we realize that herpes simplex 2 infections can occur in the oral region, we will consider the oral and maxillofacial region herpetic infections (both primary and secondary) to be represented for clinical purposes by herpes simplex 1. Serum antibody conversion of patients who have been exposed to herpes simplex 1 has decreased somewhat over the decades. Currently, in the United States, people in upper socioeconomic strata reveal a serum antibody conversion rate of only 50% to 60%. On the other hand, in undeveloped third world countries, the rate by adulthood may be as high as 95%. When considering serum conversion rates, the main thing to remember is that a large number of Americans coming into your practice may indeed have primary herpetic gingivostomatitis at any age.

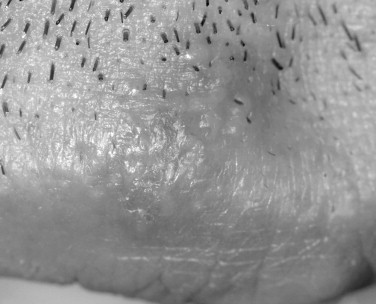

Herpes simplex viruses (HSVs) have been implicated in causing various immune-mediated reactions, including, most notably, erythema multiforme. Though secondary herpetic recurrences often create lesions, the lesions are not necessary for viral shedding. Viral shedding can occur intermittently without lesions in a significant subsample of persons who have been exposed to the virus ( Figures 31-1 and 31-2 ).

CLINICAL FEATURES

As any oral and maxillofacial surgeon knows, the two expressions of herpes simplex 1 are in the form of primary infections and secondary infections.

Primary Herpetic Gingivostomatitis

In primary infections, the patients are generally children; however, as mentioned before, as a result of the relatively low serum antibody conversion rate in the United States, primary herpetic gingivostomatitis may be diagnosed at any age. Additionally, people who are immunosuppressed can have multiple episodes of recurrent primary herpetic-like lesions. In primary herpetic gingivostomatitis, the lesions can occur on any of the oral mucosal surfaces regardless of whether they are “keratinized” or “nonkeratinized.” Classically the interdental papillae will be “punched out.” It would be rather unusual for the lesions to be localized on only one type of mucosal surface or to be unilateral. Therefore the diagnosis should be entertained only in the presence of bilateral disease affecting both keratinized and nonkeratinized mucosa. The onset of the lesions should be rather rapid and sudden. There is often cervical lymphadenopathy and an elevated temperature. If lesions involve the skin, this may portend a more severe disease course than if only the oral mucosal surfaces are involved.

Of particular note in skin lesions whether they are primary or secondary is that involvement of the tip of the nose or in areas of V1 distribution is an ophthalmologic emergency. This presentation is known as Hutchinson’s sign. If present, this herpetic involvement of the eye can result in blindness. Indeed, herpetic infections are one of the leading causes of acquired blindness in childhood.

Both skin and oral mucosal lesions generally start out as a small vesicular type of lesion that rapidly coalesces into an irregularly shaped ulcer. The individual ulcers are often surrounded by an erythematous halo. The halo region can vary in diffuseness depending on location. The primary outbreak can involve circumoral skin, the lip vermilion border, the oral mucosa, and the oropharynx, and pharyngeal tonsillitis is not unheard of. The most difficult problem with primary herpes is management of the pediatric patient in their various age groups. This is covered at length in a separate section ( Figures 31-3 and 31-4 ).

Secondary Herpes

On the oral mucosa, secondary herpes will uniquely involve the keratinized oral mucosal surfaces. This is in stark contrast to the distribution of aphthous type ulcers. The keratinized surfaces of the oral mucosa are the hard palate, dorsum of the tongue, gingivae, and lip vermilion border outside the wet line. In classic cases of recurrent herpes, a prodrome will present itself before vesicle formation. The prodrome usually starts out as a feeling of fullness with or without tingling. Generally, within the next 24 to 48 hours, vesicles will appear. As with primary herpes, these small 1- to 3-mm vesicles often coalesce. In recurrent herpes, the lesions are often unilateral, though occasional bilateral expressions may occur. These bilateral occurrences would generally be associated with some immunosuppression. Individual lesions generally last 7 to 10 days.

The reasons for recurrences are many. Triggering agents include trauma, drying, light exposure, and altered immune status. The number of Americans with a history of secondary herpes varies by report, but is probably in the range of one fourth to one third of the population.

HISTOPATHOLOGY

The virus primarily reacts within the nucleus to create changes within the nuclei of the epithelial cells. This is generally observed as an altered chromatin pattern. This chromatin pattern is generally altered to create peripheralized chromatin granules with central clearing. The nuclei are also enlarged, with the definition of the nucleolus impossible to discern. These nuclear changes have often been termed ballooning degeneration, and multinucleation is a common focal feature. The degeneration of the cells also results in loss of cohesiveness of the squamous cells. This results in free-floating acantholytic cells. These free-floating acantholytic cells are commonly called Tzanck cells.

DIAGNOSIS

The diagnosis of both primary and secondary herpes is generally clinical. The need for a biopsy is rare. Occasionally, there may be some confusion between primary herpetic gingivostomatitis and erythema multiforme. Although culture can be performed in such cases, it generally takes up to 48 hours for the culture results to return. An additional complicating factor is that viral shedding can occur in people with erythema multiforme who originally had a subclinical case of primary herpetic gingivostomatitis. In acute cases, the clinical acumen of the clinician will allow for proper diagnosis. The more difficult cases are those in immunosuppressed patients when lesions persist for long periods of time or do not conform to the 7- to 10-day period of immunocompetent patients. In these patients, a biopsy, cytology, or culture might be helpful. In some cases in which there is some clinical doubt and an intact vesicle is present, puncturing of the vesicle with immediate retrieval of cells for cytologic evaluation can be helpful. However, this is usually more for curiosity than for obtaining a definitive diagnosis before therapy.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS

We will begin with a short treatment regimen that will cover the huge majority of adult patients. These treatments are rather straightforward, though many options exist. Management of the pediatric patient is more complicated and often requires consultation.

Premise #1

Topical antivirals are not usually a first-line therapy for secondary herpetic lesions in our clinical practice. Although there are some studies that show a half-day to 1-day or more reduction in the length of the lesions with some resultant decrease in discomfort, the literature is generally clear that they help less predictably than the systemic therapies. However, looking at many of these studies, there may be a subgroup of patients that do respond very well. For instance in some studies, the half-day to 1-day reduction was actually a result of 5% to 10% of the patients never having developed a vesicle after application of the topical agent at the prodrome. Therefore the actual reduction in some reports was partially due to a small subset of patients. This appears to happen in many of these topical agents. So it seems prudent to use the topical agents if the patient already knows that they are a member of that small subset of patients who do benefit from topical agents. These topical agents are relatively expensive, and sometimes the cost of the course of topical therapy is almost the same as the systemic therapy. If used, penciclovir is better than acyclovir cream, which is better than acyclovir ointment, which is better than docosanol.

Premise #2

Although like the topical preparations, even though L-lysine may be beneficial in a subset of patients, this is not a first-line therapy. In some patients, it may act best as a prophylactic agent. Even in this case, the scientific proof of this remains sketchy.

Premise #3

In primary herpetic gingivostomatitis, the major clinical problem to address is maintenance of hydration. “Tilt tests” and other methods for hydration evaluation are highly recommended in patients with primary herpetic gingivostomatitis. These methods will be further elucidated in the section on pediatric management.

Premise #4

Of the systemic medications, the cyclovir family of drugs offers the best evidence of efficacy. Famciclovir, valacyclovir, and acyclovir can alter the systemic course of the disease whether it is primary or secondary, but they are best given within 24 to 48 hours of prodromal onset.

Premise #5

After the 48- to 72-hour window, therapy is generally limited to managing the pain and discomfort and hydration problems the patient is experiencing.

Premise #6

Systemic medications, as outlined later, appear most efficacious, though valacyclovir, famciclovir, and acyclovir are very similar by class.

SYSTEMIC AGENTS FOR HERPES SIMPLEX (ASSUMES PATIENT IS NOT IMMUNOSUPPRESSED)

Cyclovir antiviral family:

For all members of this antiviral family , use with caution in patients with renal or hepatic disease. Also consider patient’s hydration status. Headache and/or nausea are dose-related side effects and may occur in about one out of six patients.

Primary HSV

-

RX: Acyclovir 400 mg

-

Disp: 50 tablets

-

Sig: 400 mg 5 times daily for 10 days

Recurrent HSV

-

RX: Acyclovir 400 mg

-

Disp: 25 tablets

-

Sig: 400 mg 5 times daily for 5 days

ACYCLOVIR FOR HERPES LABIALIS

-

The duration of pain and time to complete healing is unaffected with doses of 400 mg t.i.d.

-

Increasing the dose to 400 mg 5 times daily decreases the duration of pain by 36% and the time to loss of crust by 27%.

-

Acyclovir is only effective if initiated very early in the recurrence.

-

Valacyclovir is the authors’ preferred drug for recurrent herpes.

-

It is a prodrug of acyclovir, which is three to five times more bioavailable than acyclovir.

-

It is in FDA pregnancy category B and has not been approved in prepubertal patients.

Suggested prescriptions for adult immunocompetent patients follow.

Primary HSV

-

RX: Valacyclovir 1-g caplets

-

Disp: 20 caplets

-

Sig: 1 g b.i.d. × 10 days

Recurrent HSV Labialis

-

RX: Valacyclovir 1 g-caplets

-

Disp: 6 caplets

-

Sig: 2 g STAT at prodrome, then 2 more 12 hours later. Save last 2 caplets to use for next outbreak. (The goal is to always have an initial dose available even if the pharmacy is closed.)

-

RX: Famciclovir 500-mg caplets

-

Disp: 6 caplets

-

Sig: 3 caplets stat at prodrome. Save 3 caplets to use for next outbreak. (The goal is to always have an initial dose available even if the pharmacy is closed.)

Prophylaxis for Recurrent HSV Infections (Immunocompetent Patients)

-

Long-term prophylaxis is indicated if patients have at least six or more herpetic outbreaks per year.

-

Reassess need every 6 to 12 months.

-

Some question the development of viral resistance; therefore long-term management is often managed by an infectious disease specialist.

-

RX: Acyclovir 400 mg

-

Disp: 60 tablets

-

Sig: Take 1 tablet q 12 hours (b.i.d.). It must be given in divided doses. Prophylactic doses between 400 to 1000 mg/day reduce the frequency of herpes labialis by 50% to 78%.

-

RX: Valacyclovir 500 mg

-

Disp: 30 caplets

-

Sig: Take 1 caplet daily

-

This is an alternative regimen for patients with greater than nine episodes per year.

-

It does not appear to have a large advantage over acyclovir 400 mg b.i.d. and is more expensive.

Over-the-counter (OTC): L-Lysine 500-mg tablets

Review of clinical trials shows lysine may have a preventive value in doses of at least 1000 mg/day. It is contraindicated with renal or hepatic impairment. Dietary supplements are not regulated for purity or efficacy. Topical Lysine does not seem to have any predictable benefit.

PEDIATRIC HERPES

Treatment of herpes in the pediatric age groups can be very difficult. Because of the wide range of how primary herpes infections affect the infant age group, the major challenge in primary herpetic gingivostomatitis is deciding when therapeutic intervention is necessary. This is a key teaching point. If observed at the right time, it may be easily diagnosed as primary herpes, but intervention is not always necessary. Generally, intervention is necessary if the patient becomes dehydrated or if the extent of the lesion extends out of the immediate perioral region. Defining what “outside the perioral region” means can vary, but a good rule of thumb is that if the herpetic lesions extend past the nasolabial fold onto the nose or below the chin onto the inferior surface of the chin, referral to the physician is indicated. Along with dehydration, these are general signs that a patient’s infection may be more severe than most.

Children’s treatment groups are broadly divided into four subdivisions, namely: infancy 0 to 2 years, preschool ages 2 to 6 years, the elementary school ages 6 to 12 years, and the adolescent ages 12 to18 years. Each of these groups presents unique challenges and therapeutic differences. The 0- to 2-years age group will not be discussed in detail. In this group, systemic therapy should always be in conjunction with the pediatrician or pediatric infectious disease physician.

In severe cases, the earlier the infection is encountered and seen to pass the immediate perioral region, the more concern there should be. Referral or cooperative therapy in conjunction with the patient’s pediatrician is often a must in these cases. The major concern in any age group, but particularly in infancy, is the possibility of either herpetic encephalitis or herpetic meningitis. Self-inoculation to involve additional sensory ganglia, especially during the initial infection, is of great concern. Keratoconjunctival extension is particularly problematic. Keratoconjunctival herpes can acutely result in blindness or possibly result in major problems later in life as a result of recurrences. Extension to involve the fingers is referred to as herpetic whitlow. Infections of the fingertip and their recurrent lesions can be very debilitating, especially in adulthood. Person-to-person spread of the viral particles is also of increased concern in these cases.

Evaluation of infants especially and children under 6 years must center on the patient’s hydration status and, to a lesser extent, their nutritional intake. Evaluation of the hydrated state of the young child and infant is complicated because of the extreme adaptability of a young person’s vascular system.

In general, the assessment for dehydration is best made through use of skin turgor, breathing rate, and capillary refill time. Capillary refill time is best accomplished by pressing on the ball of the fingertip. Normal color should be established by 2 seconds; 1.5 to 2 seconds is borderline. Turgor is measured by pinching a small skin fold on the lateral abdominal wall at the level of the umbilicus. The fold should be promptly released and the time it takes to return to normal form measured. Clear norms are not established, and results are depicted as immediate, slightly delayed, and delayed. The clinician should test multiple “normal” children to get a feel for this reaction. Lastly the respirations should be assessed from a distance, preferably as the child is in the waiting area. Respiratory cutoffs that indicate elevated rates are greater than 60/min in children under 2 months, greater than 50/min for infants 2 to 12 months, and greater than 40/min for children older than 12 months.

These three tests used together are probably the best objective method for evaluating dehydration. But experienced clinicians can observe clues for dehydration, such as chalky or dry skin and by observing the general affect of the patient.

In the preschool child, the risk of meningitis and encephalitis is reduced in comparison with the infant, but remain a concern. This risk continues to decrease the older the child is. Contradictorily the malaise associated with primary infections seems to increase with age. In all age groups, infection to other members of the family, which can cause recurrent lesions or primary infections, should not be underestimated. Likewise, day-care center settings are extreme hotbeds for possible infectious outbreaks. The younger the child, the greater the chance for oral fomite transfer to occur. The patient should be kept away from day-care centers as long as any open ulcers are present and generally 48 hours after these lesions have completely crusted. This is not a perfect system because viral shedding can continue within the saliva for days or weeks afterward and intermittently for the rest of the patient’s life.

Treatment of systemic infections centers around maintenance of hydration and nutritional intake with symptomatic relief, pain management, and reduction of the patient’s fever if present. Traditionally, pain management with topical anesthetics has centered around coating agents. In the past, viscous lidocaine was a popular ingredient in the various mixes. It cannot be overemphasized that this has changed. Currently the use of viscous lidocaine in children less than 7 or 8 years old is contraindicated, and in some communities, its use could be considered malpractice. This is due to the toxic sensitivity associated with the viscous lidocaine, and this may be related as much to the patient’s total weight as to the patient’s age. In short, the patient can experience a methemoglobinemia or cardiac arrhythmia, and without immediate intervention multiple patients have died.

Although this is a rare reaction and many of you have undoubtedly used viscous lidocaine in children under 8 years, this is a changing paradigm in pediatric care, and lidocaine should be avoided at all costs. For this reason, use of a topical anesthetic coating agent consisting of only two products, specifically, diphenhydramine hydrochloride 12.5 mg/5 mL syrup mixed with Maalox or Kaopectate. These are mixed in a 1 : 1 ratio. Two hundred milliliters is dispensed, and the patient is to rinse with 1 teaspoon every 4 hours for 2 minutes. Although the patient can swish and spit, it is also acceptable to swish and swallow. If the child cannot rinse, the use of a cotton-tipped applicator to swab the inside of the mouth is sometimes helpful. It is best to reserve the topical coating agents for children over the age of 2 years. Some adolescents or patients in the preteen age group may like the effect of topical anesthetics. For these patients, there is also some hesitance to use viscous lidocaine 2% solutions. OTC preparations, such as Chloraseptic or Orajel, may provide sufficient relief.

In these older children over age 12 years, new topical coating agents, such as GELCLAIR, may be beneficial. The key aspect on when use of GELCLAIR is appropriate is whether the patient can faithfully expectorate or not. This is used by rinsing and spitting every 3 to 4 hours. This is a better coating agent than the previously described 50/50 mix of diphenhydramine and Maalox, and many patients have expressed a preference for this material when supplied. The mainstay of treatments for all of this age group centers on the use of acyclovir or valacyclovir and when to use these medications.

In most cases, systemic antivirals should only be used if the infection is encountered in the first 48 to 72 hours. Antivirals should always be used anytime that the primary gingivostomatitis extends past the previously mentioned perioral region. In the 48- to 72-hour window, the clinician will need to use his best judgment on how the child is affected by the infection and whether intervention is necessary.

In all pediatric dosage regimens, the normal dose of acyclovir is 20 mg/kg. Acyclovir may be used in all four age groups. The maximum dose of acyclovir peaks at 800 mg. Valacyclovir and famciclovir have also been used. The famciclovir package insert is listed with two studies of patients 18 years or older. Certainly, this has been used in the adolescent group off label; however, it is probably best to keep it simple with use of either acyclovir or valacyclovir in the groups being discussed in this review. Valacyclovir has been approved for use in children 12 year or older. Studies have been conducted on children less than 12 years of age. In these studies, dosages of approximately 30 mg/kg have been safely used. Valacyclovir is a prodrug of acyclovir and is eliminated the same way as acyclovir. The one complication of valacyclovir of major importance is that it is contraindicated in patients who are immunocompromised. This limitation has generally been to patients who are on the bone marrow transplant ward or are afflicted with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection. Although not necessarily reduplicated, one study did show a higher incidence of thrombocytopenic purpura in these specific patients.

In general, valacyclovir is approved only for use in children 12 years or over. However, it has been used in younger children. There are no suspensions of valacyclovir. Some compounding pharmacies have used OraSweet as a flavoring agent to counter the very bitter taste of valacyclovir, but if there is a concern about the patient’s ability to swallow a tablet, probably the patient should receive the acyclovir rather than the valacyclovir. Acyclovir comes in varying strengths. The suspension is a 200-mg/5 mL suspension. The appropriate milliliters should be dispensed. The directions should read to take the appropriate number of milliliters that should be calculated at 20 mg/kg. This will be taken in four divided dosages with a maximum dose of 50 mg/kg/day.

Herpes gingivostomatitis remains a complicated disease to control. It is extremely common, with 60% of the population having been exposed to the virus by age 21 years. There are many factors in the recurrence rate and exposure causes, but the most important aspect of treatment is a proper diagnosis and assessment of the patient to decide whether systemic therapy or symptomatic therapy is the best approach for that particular patient.

HERPANGINA

Herpangina is a disease that generally occurs in epidemic fashion throughout the world. Some of the most well-documented epidemics occurred throughout areas of eastern Asia, most notably Taiwan and Japan. Although herpangina will be the disease primarily discussed in this section, perhaps the best way to think of this group of diseases is under the heading of enterovirus diseases . Within this group would be herpangina, hand-foot-and-mouth disease, and acute lymphonodular pharyngitis. These diseases probably vary only in clinical phenotypic presentation and have great overlap in the actual virus that acts as a causative agent for each.

The enteroviruses are complicated by historical inconsistencies in nomenclature and evolvement of the classification system itself. The enteroviruses are a subset of the picornavirus family. As such, they are RNA viruses. The Coxsackie virus species were first described by a laboratory in Coxsackie, New York. The echovirus species were first named because investigators believed that the members of this family were not pathogenic in man. As such, the “echo” in echovirus originally stood for enteric cytopathogenic human orphan virus. However, time has told us that they are indeed pathogenic. Other branches of the enterovirus family are rhinovirus, poliovirus, aphthovirus, cardiovirus, and hepatovirus categories. Additionally, there are some unclassified members of the family, and recently discovered members of the family have generally been named by number beginning with enterovirus 68 and now including members or proposals through enterovirus 73. Of these recently described enteroviruses, enterovirus 71 is particularly important clinically. This will be emphasized later in the discussion.

The Coxsackie virus family is generally divided into Coxsackie A and Coxsackie B groups. In the Coxsackie A group, there is a total of 23 types, although the numbers range from A1 to A24 with no A23. The Coxsackie B group consists of six members with B1 to B6 represented. The echoviruses are numbered 1 to 34, although two numbers are not represented for a total of 32 ( Figure 31-5 ).

CLINICAL FINDINGS

These diseases are generally classified under the exanthemas. Exanthemas are represented by such common diseases as measles, rubella, and rosella to name a few. When lesions involve the oral mucosa, the term is called enanthema. In past times, it was feasible to memorize for test-taking purposes which enteroviruses could possibly cause herpangina. Now with 21 different members of the family having been associated with herpangina, it is best to just think in generalities. The most common types associated with herpangina are within the Coxsackie A group. Of most clinical significance is the possibility that enterovirus 71 may cause herpangina. Enterovirus 71 can cause severe symptoms and has resulted in a number of reported deaths. Complications of enterovirus 71 and occasionally other members of the enterovirus group include meningitis, pulmonary edema, paralysis, and severe CNS symptoms. In these more severe cases, the fever tends to be more elevated for a longer period of time and general presentation of the symptoms is also more severe. Thus the clinician is warned that in cases of hand-foot-and-mouth disease, herpangina, or lymphonodular pharyngitis, if the systemic symptoms appear to be severe, further delineation of the viral subtype may be warranted. Viral subtyping can be performed on stool samples and by culture and subsequent analysis. Fortunately, these severe manifestations are rare, and in the common presentation, the diagnosis is generally made through simple clinical observation. With that said, serologic and culture tests may be performed.

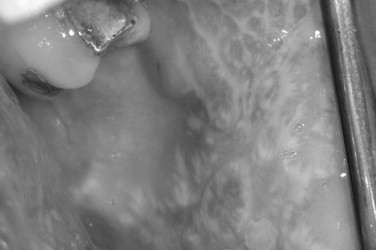

The oral ulcers of herpangina are one of the first presenting signs of the disease. The oral ulcers generally occur as only a handful of vesicles. The vesicles are often fragile and surrounded by a small region of erythematous change. The individual vesicles are generally small and on the order of 2 to 4 mm. Locations of the ulcers are almost always confined to the soft palate, faucial pillars, and the tonsillar bed of the palatine tonsils. In the clinical setting of hand-foot-and-mouth disease, the vesicles are not limited to the posterior portion of the oral cavity and may occur on other anterior surfaces. In addition, there are often more numerous vesicles, on the order of 15 to 25. In addition to the oral mucosa in hand-foot-and-mouth disease, either the hands or feet should be involved.

Following the oral vesicles, flulike symptoms will quickly ensue and persist over several days. Although these systemic flulike symptoms resolve, if they are severe or long lasting, consideration of the enterovirus 71 complications could be very important. Flulike symptom examples include cough, malaise, lymphadenopathy, nausea, rhinorrhea, muscle ache, and diarrhea.

HISTOPATHOLOGY

As reported by Neville et al, the histopathologic features of a biopsy are nonspecific, with disruption of the epithelium. Inflammatory cells and intracellular and intercellular edema are also noted. The vesicle itself tends to be intraepithelial.

TREATMENT

As mentioned previously, the disease is generally self-limiting with no need for therapeutic intervention. Supportive care for the various symptoms is often necessary. These generally center around use of antipyretics, antiemetics, antidiarrheals, and analgesics. As with herpes, assessment of the patient’s hydration status is important, and proper instructions for hydration should be established. Referral to an infectious disease consultant, pulmonary specialist, pediatrician, or primary care provider may be necessary in many cases. Isolation of the patient to prevent epidemic spread of the disease is necessary. Transmission can be by respiratory droplet or saliva in the acute phase, though the oral-fecal route of transmission is probably the most common method of epidemic transmission. Therefore good hygiene practices and isolation of the patient are advised. Epidemics are most common in crowded conditions, with the summer months and early fall being the most common times of year.

HERPANGINA

Herpangina is a disease that generally occurs in epidemic fashion throughout the world. Some of the most well-documented epidemics occurred throughout areas of eastern Asia, most notably Taiwan and Japan. Although herpangina will be the disease primarily discussed in this section, perhaps the best way to think of this group of diseases is under the heading of enterovirus diseases . Within this group would be herpangina, hand-foot-and-mouth disease, and acute lymphonodular pharyngitis. These diseases probably vary only in clinical phenotypic presentation and have great overlap in the actual virus that acts as a causative agent for each.

The enteroviruses are complicated by historical inconsistencies in nomenclature and evolvement of the classification system itself. The enteroviruses are a subset of the picornavirus family. As such, they are RNA viruses. The Coxsackie virus species were first described by a laboratory in Coxsackie, New York. The echovirus species were first named because investigators believed that the members of this family were not pathogenic in man. As such, the “echo” in echovirus originally stood for enteric cytopathogenic human orphan virus. However, time has told us that they are indeed pathogenic. Other branches of the enterovirus family are rhinovirus, poliovirus, aphthovirus, cardiovirus, and hepatovirus categories. Additionally, there are some unclassified members of the family, and recently discovered members of the family have generally been named by number beginning with enterovirus 68 and now including members or proposals through enterovirus 73. Of these recently described enteroviruses, enterovirus 71 is particularly important clinically. This will be emphasized later in the discussion.

The Coxsackie virus family is generally divided into Coxsackie A and Coxsackie B groups. In the Coxsackie A group, there is a total of 23 types, although the numbers range from A1 to A24 with no A23. The Coxsackie B group consists of six members with B1 to B6 represented. The echoviruses are numbered 1 to 34, although two numbers are not represented for a total of 32 ( Figure 31-5 ).

CLINICAL FINDINGS

These diseases are generally classified under the exanthemas. Exanthemas are represented by such common diseases as measles, rubella, and rosella to name a few. When lesions involve the oral mucosa, the term is called enanthema. In past times, it was feasible to memorize for test-taking purposes which enteroviruses could possibly cause herpangina. Now with 21 different members of the family having been associated with herpangina, it is best to just think in generalities. The most common types associated with herpangina are within the Coxsackie A group. Of most clinical significance is the possibility that enterovirus 71 may cause herpangina. Enterovirus 71 can cause severe symptoms and has resulted in a number of reported deaths. Complications of enterovirus 71 and occasionally other members of the enterovirus group include meningitis, pulmonary edema, paralysis, and severe CNS symptoms. In these more severe cases, the fever tends to be more elevated for a longer period of time and general presentation of the symptoms is also more severe. Thus the clinician is warned that in cases of hand-foot-and-mouth disease, herpangina, or lymphonodular pharyngitis, if the systemic symptoms appear to be severe, further delineation of the viral subtype may be warranted. Viral subtyping can be performed on stool samples and by culture and subsequent analysis. Fortunately, these severe manifestations are rare, and in the common presentation, the diagnosis is generally made through simple clinical observation. With that said, serologic and culture tests may be performed.

The oral ulcers of herpangina are one of the first presenting signs of the disease. The oral ulcers generally occur as only a handful of vesicles. The vesicles are often fragile and surrounded by a small region of erythematous change. The individual vesicles are generally small and on the order of 2 to 4 mm. Locations of the ulcers are almost always confined to the soft palate, faucial pillars, and the tonsillar bed of the palatine tonsils. In the clinical setting of hand-foot-and-mouth disease, the vesicles are not limited to the posterior portion of the oral cavity and may occur on other anterior surfaces. In addition, there are often more numerous vesicles, on the order of 15 to 25. In addition to the oral mucosa in hand-foot-and-mouth disease, either the hands or feet should be involved.

Following the oral vesicles, flulike symptoms will quickly ensue and persist over several days. Although these systemic flulike symptoms resolve, if they are severe or long lasting, consideration of the enterovirus 71 complications could be very important. Flulike symptom examples include cough, malaise, lymphadenopathy, nausea, rhinorrhea, muscle ache, and diarrhea.

HISTOPATHOLOGY

As reported by Neville et al, the histopathologic features of a biopsy are nonspecific, with disruption of the epithelium. Inflammatory cells and intracellular and intercellular edema are also noted. The vesicle itself tends to be intraepithelial.

TREATMENT

As mentioned previously, the disease is generally self-limiting with no need for therapeutic intervention. Supportive care for the various symptoms is often necessary. These generally center around use of antipyretics, antiemetics, antidiarrheals, and analgesics. As with herpes, assessment of the patient’s hydration status is important, and proper instructions for hydration should be established. Referral to an infectious disease consultant, pulmonary specialist, pediatrician, or primary care provider may be necessary in many cases. Isolation of the patient to prevent epidemic spread of the disease is necessary. Transmission can be by respiratory droplet or saliva in the acute phase, though the oral-fecal route of transmission is probably the most common method of epidemic transmission. Therefore good hygiene practices and isolation of the patient are advised. Epidemics are most common in crowded conditions, with the summer months and early fall being the most common times of year.

LICHEN PLANUS

Lichen planus is a relatively common inflammatory mucocutaneous disease with a distinct morphology, affecting approximately 2% of the general population. It commonly affects middle-aged adults with a slight preponderance in women. Oral lesions can be seen alone or in combination with cutaneous disease. In contrast to skin involvement, oral lichen planus tends to be more persistent and refractory to treatment. Whether oral lichen planus constitutes a premalignant lesion remains controversial. A relatively low incidence of malignant change in oral lichen planus has been reported in some serial studies and is usually confined to patients with less common erosive or atrophic forms of oral lichen planus ( Figure 31-6 ).

ETIOLOGY

The pathophysiology of lichen planus is not fully understood, but is thought to be an autoimmune-mediated disease triggered by antigenic alterations on the cell surface of the basal layer of the epithelium. Langerhans cells act as antigenpresenting cells to T lymphocytes, stimulating their proliferation, with subsequent epithelial changes in a similar mechanism to allergic contact dermatitis. Whereas many cases of lichen planus are idiopathic, some cases are linked to the use of medications, dental restorative materials, and, in some populations, infection with the hepatitis C virus. The association of certain medications and oral lichenoid lesions has been well described.

CLINICAL FEATURES

Cutaneous lesions seen in lichen planus include violaceous polygonal papules and plaques. Upon closer examination, a delicate reticulated pattern of white scales, known as Wickham’s striae , is observed. Some have described the classic cutaneous lesions of lichen planus as pruritic, polygonal, planar (flat-topped), purple papules and plaques. The flexor surfaces of extremities are commonly involved, and dystrophic changes in the nail beds can sometimes be seen. Lesions may erupt on surfaces exposed to trauma in a response known as the Koebner phenomenon . This tissue response to trauma can also be seen in oral lichen planus.

Reticular and erosive lichen planus are the two main forms of oral lichen planus, and it is not uncommon for patients to have a combination of both forms. Reticulated oral lichen planus is the most common form and generally occurs as asymptomatic delicate interlacing white striae found in a bilateral distribution. The buccal mucosa is the most common site of involvement followed by the tongue, gingiva, and lips. An uncommon variant of reticulated oral lichen planus, known as plaque-type lichen planus, is sometimes found on the dorsal surface of the tongue and on the buccal mucosa and can clinically resemble leukoplakia.

Erosive oral lichen planus appears as irregular centrally ulcerated atrophic and erythematous lesions often with fine white lacelike striae at the periphery. Erosive lichen planus tends to be a multifocal process with the degree and morphology of the erythematous and ulcerated lesions changing over time. Bullous and atrophic oral lichen planus are believed to represent variants of erosive lichen planus. Typically symptomatic, patients with erosive lichen planus complain of a painful burning sensation that can be debilitating and exacerbated by diet. Erosive lichen planus is sometimes limited to the gingiva and can present clinically as a painful desquamative gingivitis. In some patients, a characteristic erosive gingival and genital involvement has been described in a syndrome complex referred to as the vulvovaginal-gingival syndrome .

HISTOPATHOLOGY AND LABORATORY STUDIES

Although the clinical presentation of reticulated oral lichen planus can sometimes be characteristic for the disease, a biopsy is recommended to confirm the clinical diagnosis. In erosive lichen planus, it can be essential in excluding other inflammatory and neoplastic diseases. The histopathologic features of idiopathic lichen planus are characteristic, but not specific because other lichenoid lesions can show similar features on light microscopy. Microscopic examination typically shows an intense bandlike lymphocytic infiltrate at the epithelialconnective tissue interface with vacuolar degeneration of the basilar epithelial layer. Varying degrees of hyperkeratosis of the surface epithelium are seen, and the spinous layer can be hyperplastic, ulcerated, or atrophic depending on the clinical form of oral lichen planus. Scattered degenerating keratinocytes or colloid bodies can sometimes be found within the deeper epithelial layers. Direct immunofluorescence (DIF) studies can be helpful in differentiating erosive lichen planus from other vesiculobullous diseases. Skin-patch testing is sometimes performed in suspected cases of lichenoid contact lesions. Hepatitis C testing is recommended for newly diagnosed cases of oral lichen planus in some populations.

TREATMENT

Patients with asymptomatic reticular lichen planus usually require no additional treatment other than periodic clinical follow-up once the diagnosis is established. Topical and systemic corticosteroids used alone or in combination are the most widely accepted therapy for erosive and symptomatic cases of oral lichen planus. Short term use of systemic corticosteroids can be effective in the initial control of the disease or in cases refractory to topical therapy, but their inherent toxicity limits their usage in the treatment of chronic disease. Other innovative therapies used in recalcitrant cases include the use of tacrolimus, retinoids, and immunosuppressant and cytotoxic drug therapy. Concomitant antifungal therapy is useful in reducing the incidence of candidiasis during corticosteroid and other immunosuppressant therapy.

APHTHOUS STOMATITIS

Recurrent oral aphthous ulcerations are often a frustrating, lifelong curse for both patients and practitioners alike because no single treatment modality is totally curative and no clearly defined cause has been identified. Commonly referred to as canker sores, these painful oral ulcers occur in three clinical variations: minor, major, and herpetiform lesions. In most studies, 30% of the population is affected, with a higher prevalence seen in whites younger than 40 years of age and females outnumbering males. In addition to genetic and familial factors, environmental and stress-related influences have been implicated as a cause for recurrent aphthous stomatitis.

Many factors are believed to initiate aphthous stomatitis, including medications, such as Cox-2 inhibitors, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and antidepressants. Anxiety or stress, hormonal changes, allergies, nutritional deficiencies, and antigen exposure, which produces a hypersensitivity reaction as a result of minor trauma or bacterial infiltration, are all factors in the development of aphthous lesions. A tendency toward a familial inheritance pattern has also been observed ( Figure 31-7 ).

CLINICAL FEATURES

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses