HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

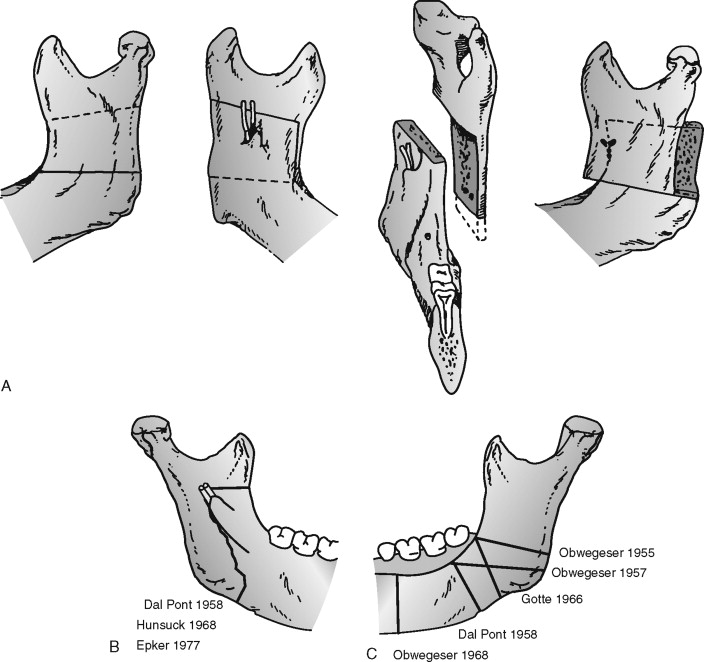

Bilateral sagittal split osteotomy (BSSO) of the mandible is one of the most frequently performed surgical procedures. Originally developed in the middle of the last century by Hugo Obwegeser, at the Department of Surgery, Medical University of Graz, Austria, the technique quickly found its way into the armamentarium of surgical procedures in orthognathic surgery. Two major characteristics delineated Obwegeser’s technique from standard techniques used at that time: (1) It was the first surgical procedure performed to lengthen the skeletal mandible, and (2) the technique permitted intraoral access to the operating site, which had been strictly forbidden because infections resulted in disastrous complications. “Although in those days it was generally strictly forbidden in bone grafting to open the oral cavity, even for the size of a pin head, I had learned in treating mandibular fractures that infection is rarely to be expected when intermaxillary fixation is achieved within 24 hours after the accident. So I was not frightened about the risk of infection.” In April 1953, the first patient ever to undergo this operation was treated by Obwegeser intraorally on one side; the other side was treated by the head of the department at that time, Richard Trauner, who performed the usual L-shaped osteotomy from outside. This specific technique of sagittal split osteotomy was not published internationally by Obwegeser until 1957 ( Figure 3-1, A ).

At that time, it had already been published in the German literature by Karl Schuchardt, a maxillofacial surgeon from Hamburg, Germany, who happened to visit Obwegeser in Graz just at the time when he performed the first operation, as described previously. Several months later, after returning to Hamburg, Schuchardt performed the procedure on a patient himself, named the procedure “schräge Osteotomie” (oblique osteotomy), and published it locally in 1954.

Early on, a modification was experimentally developed by Giorgio Dal Pont but was never used clinically. Dal Pont had been an assistant surgeon to Obwegeser and had tried to modify the procedure to create a larger osseous surface of the split fragments so as to alleviate osteosynthesis ( Figure 3-1, B ). He extended the primary osteotomy in the direction of the horizontal part of the mandible. After returning to Italy, Dal Pont published his experimental work on jaw models and cadavers there and in the United States without having performed the technique himself. Nevertheless, Obwegeser’s technique occasionally is erroneously addressed as the Obwegeser-Dal Pont procedure.

Other modifications of Obwegeser’s osteotomy followed. The Hunshuck/Epker modification is a variation of the lingual cut ( Figure 3-1, C ). The original cut, which usually ends at the posterior border of the ascending ramus, occasionally is difficult to perform in its full length in patients with strong bony appositions. In these patients, the procedure can be performed successfully even without a full-length cut; it ends immediately behind the entrance of the inferior alveolar nerve.

One benefit of this procedure might be that the muscles of mastication remain attached to the proximal segment. This makes positioning of the temporomandibular joint (TMJ) easier and may reduce relapse because tension on the distal segment is lessened. A possible disadvantage, particularly for large advancements, is the resultant smaller bony interface between the two osteotomized fragments.

Postoperative fixation of bone fragments after osteotomy was once a major challenge for surgeons. Initially, separated fragments were not fixed and healing after osteotomy was achieved simply via intermaxillary splinting of teeth together for several weeks. This led to considerable instability of osteotomized fragments with the consequence of delayed or even insufficient healing. Later on, stabilization was improved by introduction of additional wire fixation. Both procedures resulted in intermaxillary fixation for many weeks, which created a heavy physical and psychological burden for patients and occasionally resulted in insufficient healing and stability.

A major breakthrough came with the development of stable compression osteosynthesis, which was introduced in 1974 by B. Spiessl from Switzerland and consecutively replaced osteosynthesis by wire fixation or intermaxillary fixation. Spiessl used steel plates and screws to keep the fragments of the mandible in a fixed position. The degree of immediate postoperative stability achieved with this technique turned out to completely obviate the need for intermaxillary fixation.

Additional improvements were made when different materials such as stainless steel or titanium were used for osteosynthesis. These materials produced significantly reduced local reactions such as infection or severe septicemia because metal implants per se can act as a nidus for bacterial growth. In addition, plates could be grafted that were thinner than those ever used before without loss of stability. Finally, plates could be shaped easily to perfectly adapt to local anatomic structures.

Nevertheless, these new materials still represented foreign material and had to be removed occasionally after a considerable time because they produced local or systemic inflammatory reactions. Therefore, researchers continued working to develop material for osteosynthesis that would degrade by itself. In the late 1960s, absorbable implants were introduced for the repair of bone fractures. Pins and rods were fabricated by melt, mold, and extrusion of polymer. Subsequently, in the late 1970s and early 1980s, more complex designs such as screws and small plates allowed their use in orthognathic surgery procedures. First experiences with 2-mm self-reinforced polylactate (PLLDL) (70/30) screws were promising, and the screws showed good stability after bilateralused sagittal osteotomy was performed for mandibular advancement. The difference in these screws in terms of 1-year stability and outcome is minimal. Recently, these first findings with self-reinforced polylactate bone plates and screws were confirmed by good success on short-termstabilize observation.

INDICATIONS FOR BILATERAL SAGITTAL SPLIT OSTEOTOMY

Since its introduction in 1956, bilateral sagittal split osteotomy has become the most widely used surgical procedure for correction of malposition of the mandible. It has been modified in many ways, but for longer than 50 years, benefits and advantages of the procedure have remained unchanged ( Box 3-1 ).

-

Great three-dimensional flexibility in repositioning the distal fragments which allows accurate intraoperative positioning of the fragments

-

Broad bony overlap of osteotomized segments which results in excellent healing

-

Minimal alteration of the natural position of muscles of mastication which prevents relapse from muscular traction

-

Minimal alteration of the original position of the temporomandibular joint which minimizes the risk of postoperative athropathy

-

Short operating time and low complication rate

The design of the surgical cut as proposed by Obwegeser and the various modifications as proposed by a number of surgeons are especially effective for all surgical corrections of mandibular deformity.

The versatility of the procedure allows wide application in both mandibular advancement and mandibular setback. It tremendously increases the range of possible movements compared with orthodontic treatment alone, as demonstrated by Proffit’s envelope of discrepancy. The broad bony overlaps of the separated fragments allow not only advancement or setback of the distal tooth-baring mandible, but also rotations. Even with wide movements, bony interfaces are sufficient to allow excellent healing. Muscles of mastication stay attached to the proximal segment at the gonial angle. With rigid fixation from an intraoral approach, little detachment of muscles is necessary. This technique results in very little muscle traction, a condition that helps to prevent long-term relapse. Because the muscles of mastication stay attached to bone, it is easier to position the condyle during osteosynthesis. Correct positioning of the condyle is required if postoperative arthropathy is to be avoided.

The surgical procedure itself is a standardized method that helps to minimize the risk of complications and that shortens operating time.

MANDIBULAR DEFICIENCY

Mandibular deficiency is the most common dentofacial deformity that requires surgical orthodontic treatment. In the National Health And Nutrition Estimates Survey (1989-1994; NHANES III), about 2% of the adult population in the United States reported that they had deviations from the ideal bite that were severe enough to be handicapping. The prevalence of severe class II malocclusion (>6 mm overbite) was found to be 4.3% among those aged 18 to 50 years, and only 0.3% of the population had severe class III malocclusion (>3 mm overjet) that required surgical orthodontic treatment ( Box 3-2 ).

-

Increased A/B difference

-

Class II canine and molar relationship

-

Increased overjet if not compensated by retrusion of the upper incisors

-

Excessive curve of Spee in the mandible, sometimes combined with reduced curve of Spee in the maxilla

-

Incisor crowding, more often in the upper jaw than in the lower jaw

-

Tendency to develop a deep labiomental fold

The term mandibular deficiency solely reflects the anatomic position of the mandible in relation to the maxilla. The sagittal discrepancy between maxilla and mandible caused by underdevelopment of the mandible results in a class II dental relationship. This posterior movement in the horizontal axis during growth may go along with changes in the vertical axis, resulting in an increase or decrease in frontal facial height ( Case Reports 3-1 through 3-3 ).

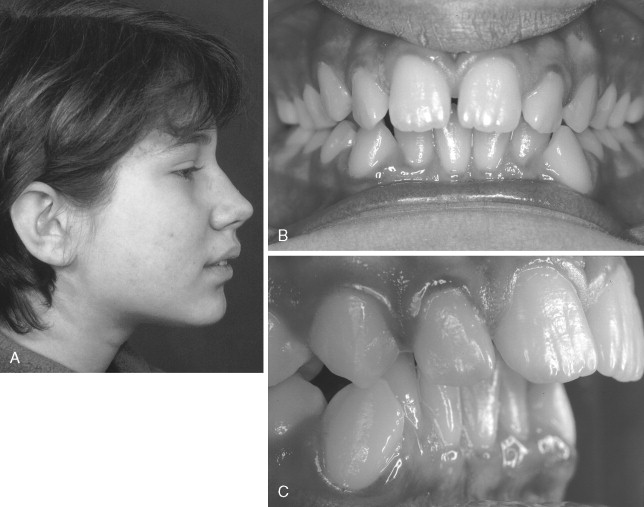

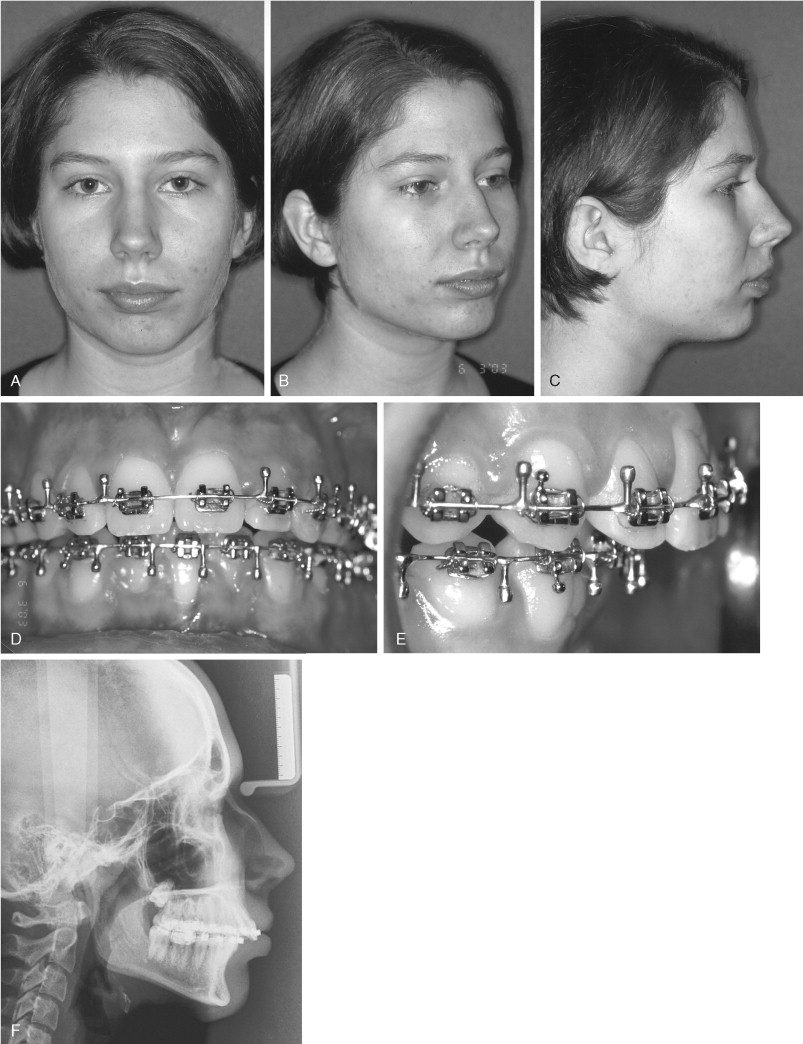

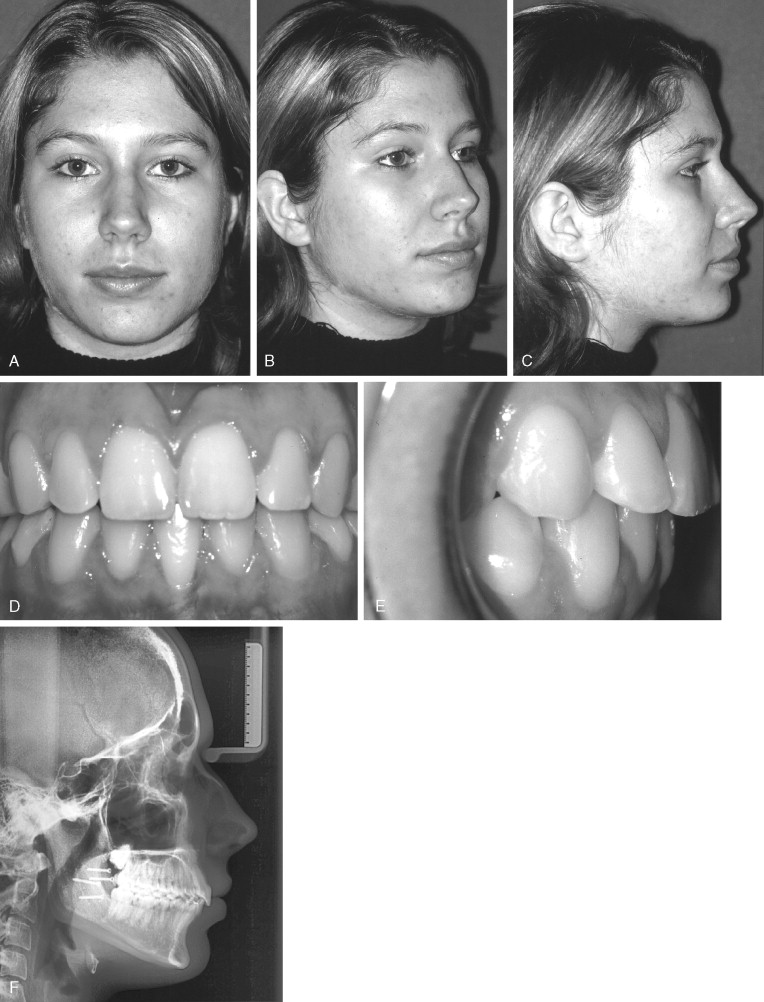

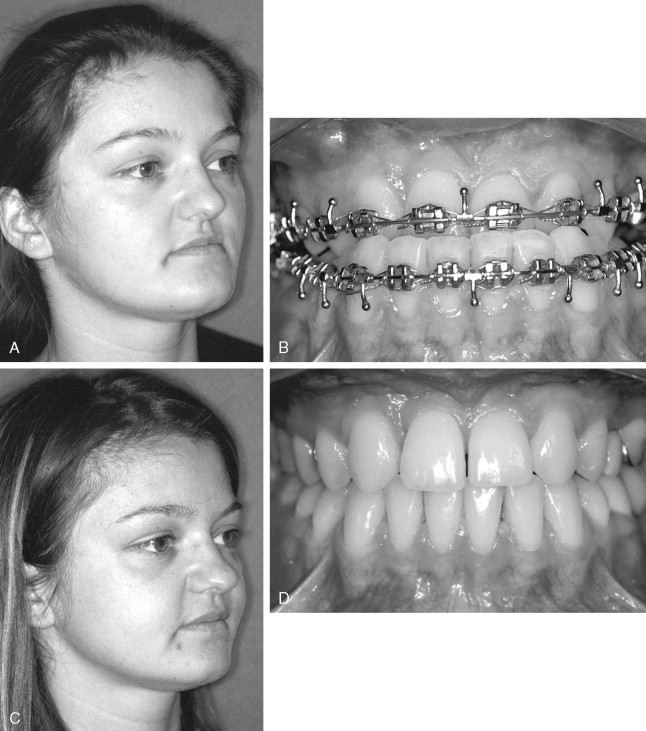

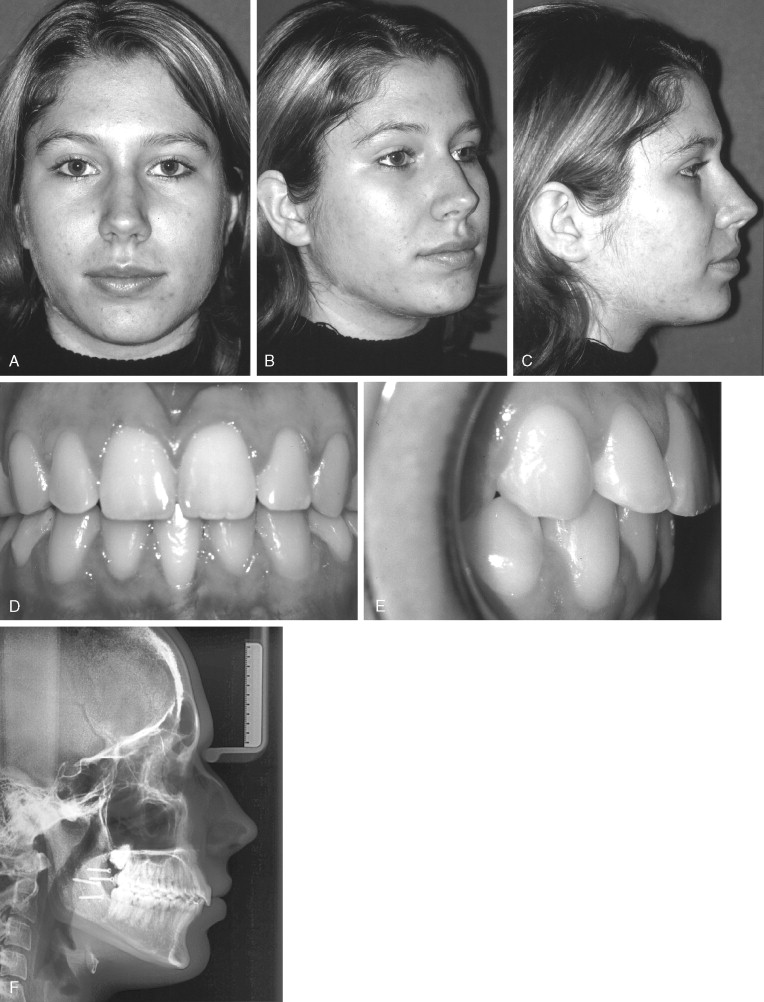

R.J. was referred for orthodontic treatment at age 12. She presented with class II malocclusion and severe crowding in the lower arch. She wanted her teeth fixed and hadn’t liked her teeth for as long as she could remember ( Figure 3-2 through 3-4 ).

Oral health was good, and some bone loss was evident at the right medial lower incisor. R.J. had some clicking in the right joint and occasional pain.

On clinical examination of the face, AP mandibular deficiency was noted. Combined orthodontic-surgical treatment was suggested. Her parents believed she was too young for surgery at this point. Because of the joint pain, splint therapy was suggested. Orthodontic treatment was started when R.J. was 15 years old. Cephalometric analysis confirmed AP mandibular deficiency. At that time, bone loss at both of the medial lower incisors had worsened.

The treatment plan was as follows: To align the crowded lower arch, the left lower medial incisor had to be extracted; because some bone loss was apparent and all other teeth were in good health without caries, BSSO to advance the mandible was recommended.

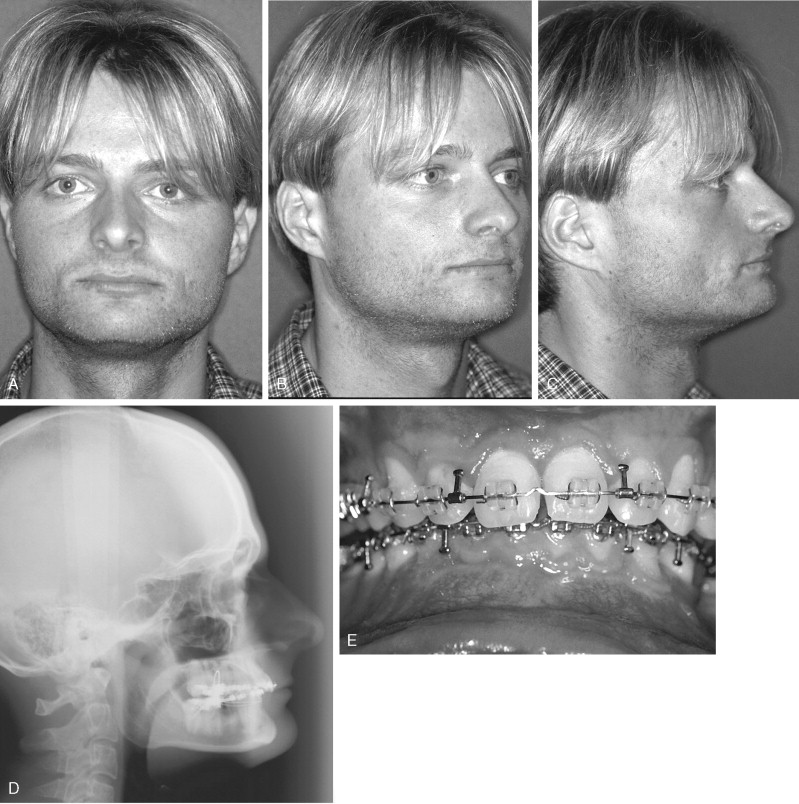

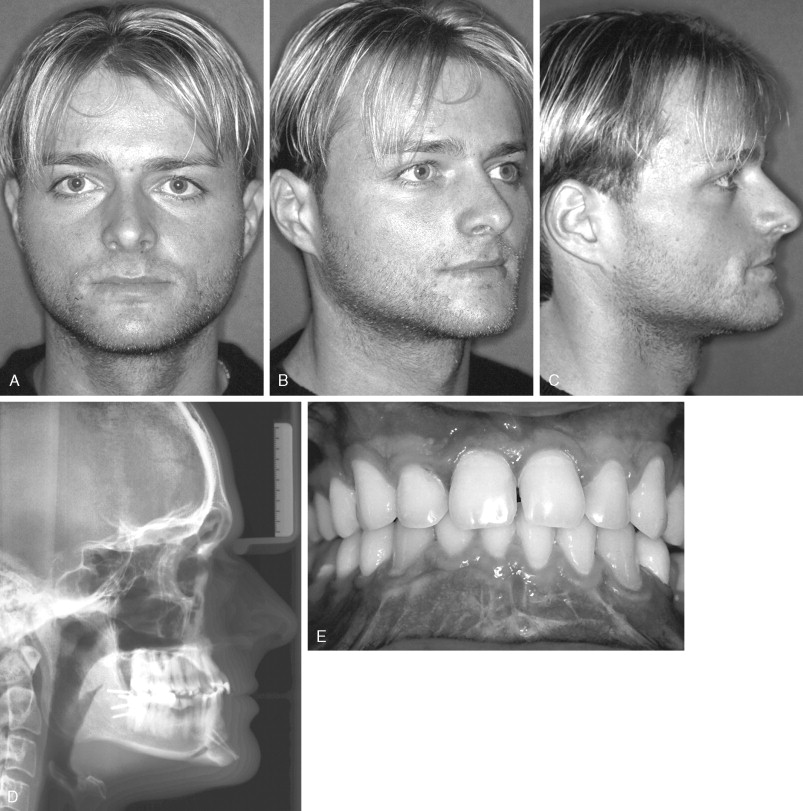

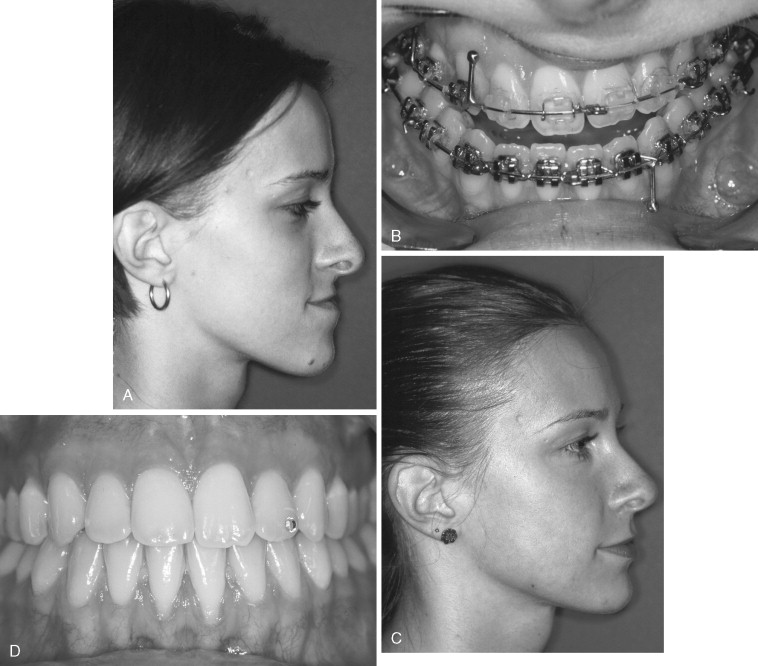

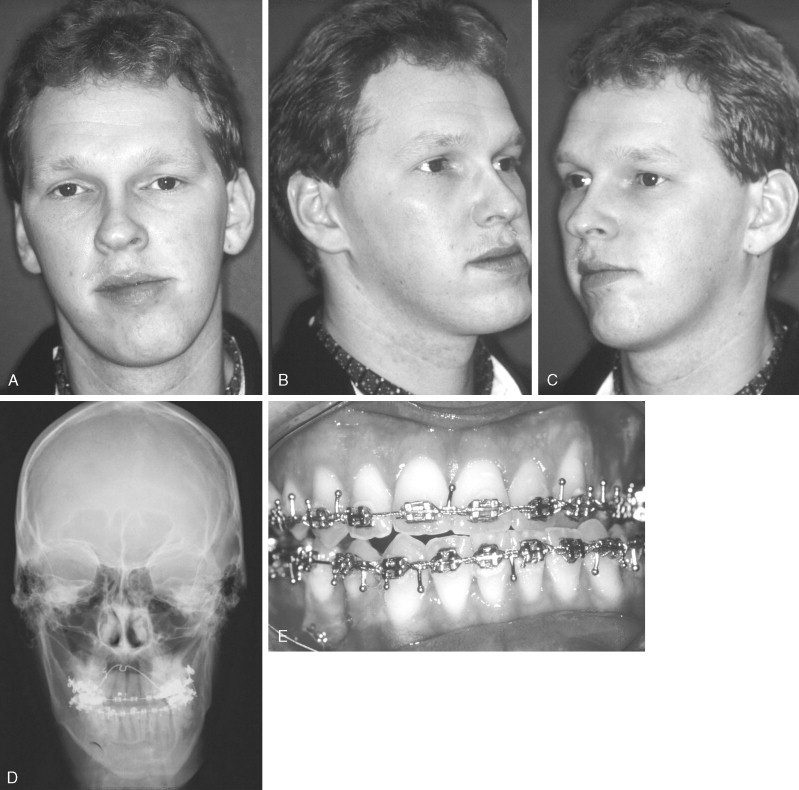

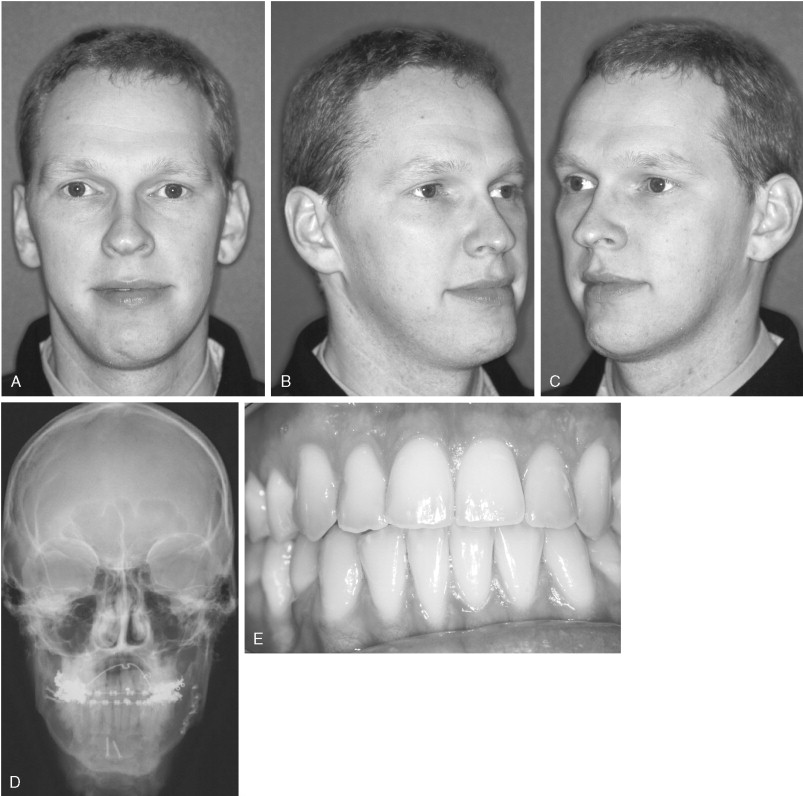

This 25-year-old patient was seeking orthodontic treatment because of a deep bite that caused inflammation lingual to the maxillary teeth ( Figures 3-5 and 3-6 ). He had some facial esthetic concern because of the strong chin button, but this was not his main reason for seeking orthodontic treatment. The patient had difficulty with chewing and pain because of the inflammation, which had increased in intensity and duration over previous months.

On clinical examination, the periodontal condition was good except for severe inflammation lingual to the maxillary incisors. He had 10 mm overjet and 7 mm overbite. He had lost his left lower first molar because of caries, but oral health was good. Lower face height was short with a strong chin button, a retrusive lower lip, and an exaggerated labiomental fold. Cephalometric analysis showed AP mandibular deficiency and skeletal deep bite with the mandible rotated upward and forward.

The treatment plan was as follows: BSSO should be performed to advance the mandible and rotate the distal segment to increase the mandibular plane angle and correct the deep bite, followed by inferior border osteotomy to further increase lower face height.

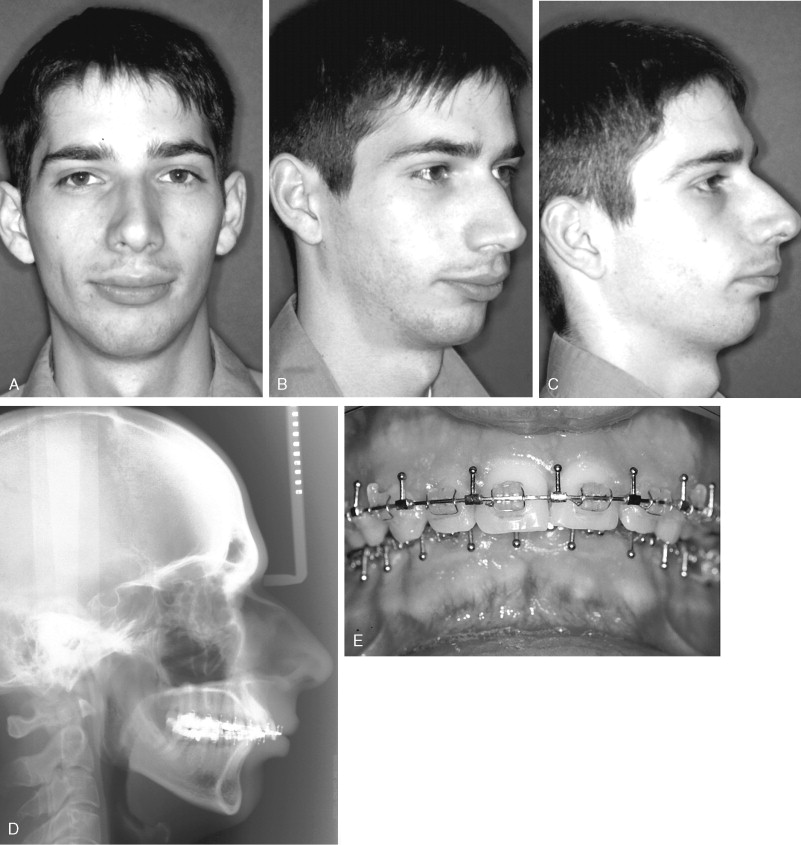

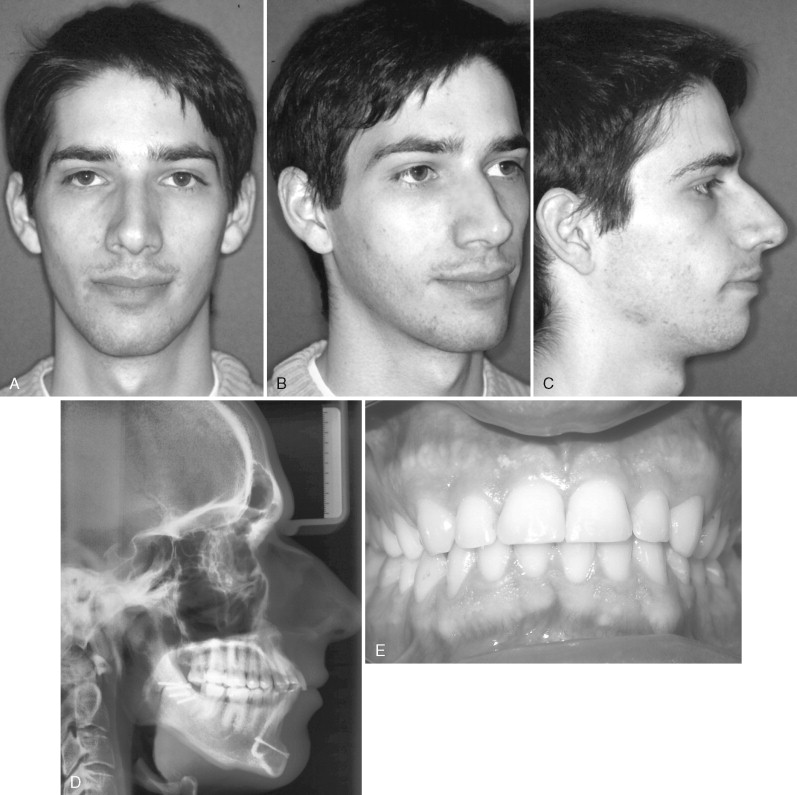

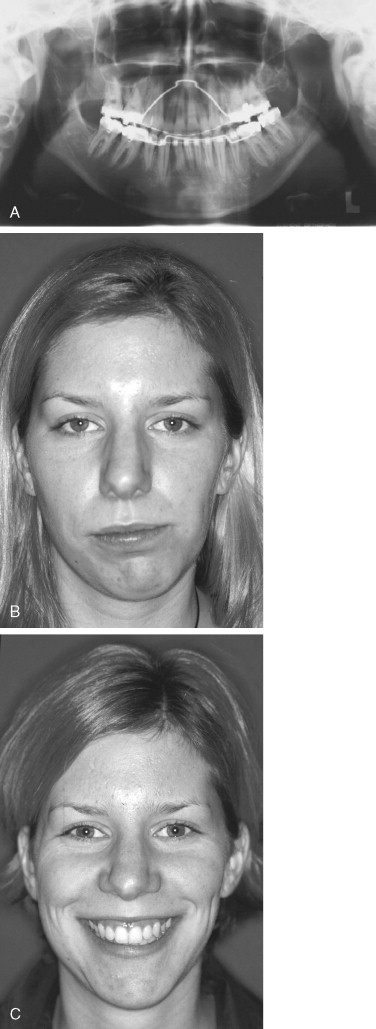

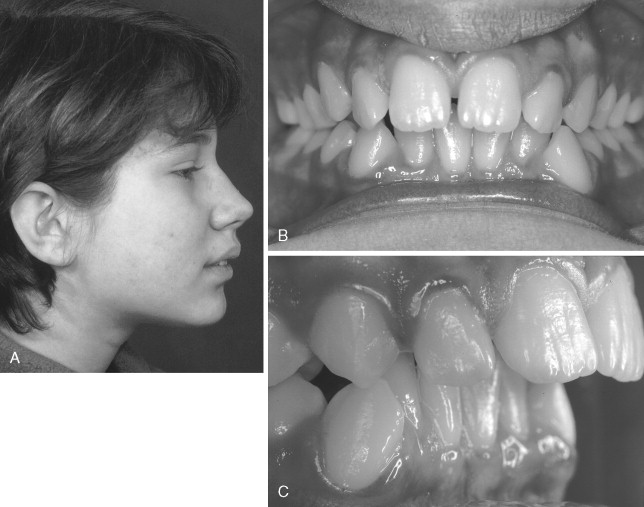

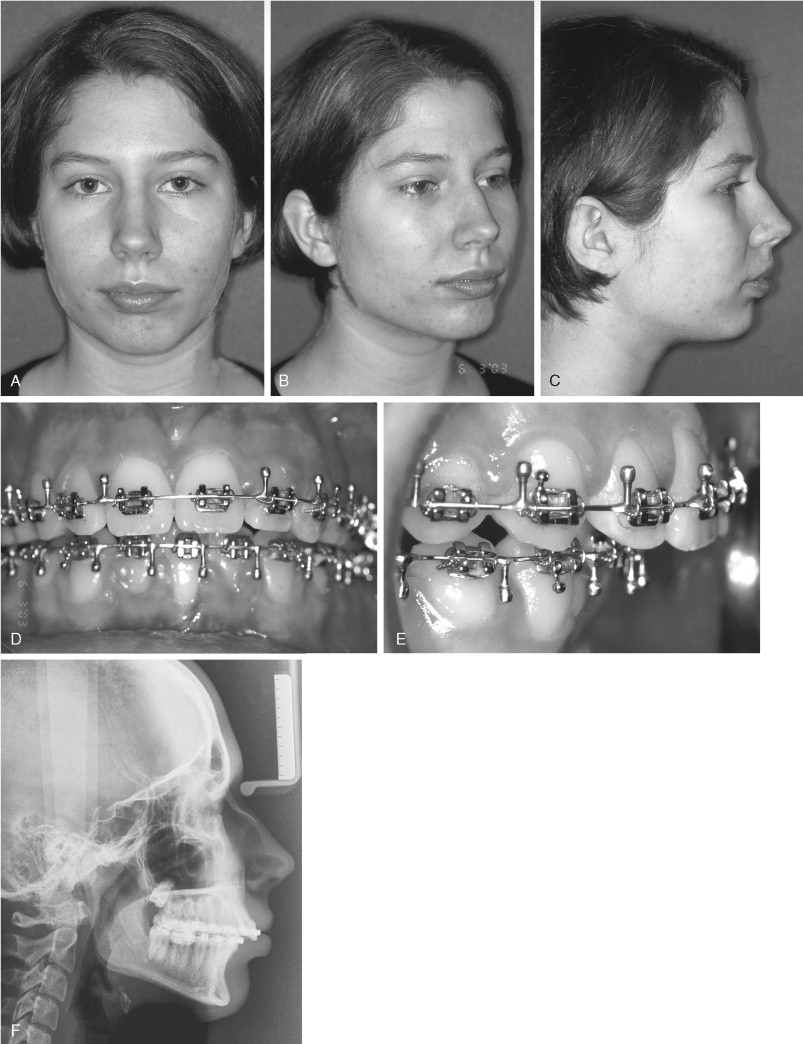

This 24-year-old student was referred for combined surgical-orthodontic treatment. The patient’s chief concerns were his deep bite and the fact that his teeth did not fit together properly. He found that his chin was a little deficient and that he had a “protrusive maxilla.” He underwent orthodontic treatment when he was a child for about 3 years. He felt very uncomfortable with his profile, and chewing was difficult. Clinical examination showed a good nasolabial angle. The long face deformity was due to excessive length of the chin. Clicking was noted in both joints as was 9 mm overjet and 8 mm overbite; the dental midline was slightly off to the right side ( Figures 3-7 and 3-8 ).

The treatment plan for this patient included BSSO to correct the mandibular deficiency and rotation at the gonial angle to correct the deep bite. For correction of the retrogenia and reduction of increased anterior face height, an inferior border osteotomy was planned.

Mandibular deficiency is the most frequent indication for BSSO. Its oblique cut creates a large interface between osteotomized fragments. This allows rotation of fragments and their movement in all directions without loss of critical surface for stable osteosynthesis. Postoperative stability is generally excellent but is dependent on many factors such as extent and direction of movement.

Correction of mandibular deficiency by anterior movement along the mandibular plane is one of the most stable procedures, although it is dependent on the amount of anterior movement. This is true only in patients with normal anterior facial height and normal overbite when no rotation at the gonial angle is necessary (see Case Report 3-1 ).

The situation is a little different when the distal teeth–carrying segment has to be rotated. Clockwork rotation, which is the result of deep bite correction, generates an increase in anterior facial height (see Case Report 3-2 ). This increase occurs at the cost of some loss of stability and results in remaining or decreased posterior facial height, which has an additional impact on facial width. Overall, postoperative stability is acceptable and relapse is rare. To reduce anterior facial height without an inferior border osteotomy (genioplasty), counterclockwise rotation of the distal fragment is necessary. However, this results in loss of stability on long-term follow-up investigations because soft tissue stretch of the pterygoid muscle sling makes skeletal relapse possible. Therefore, compromises should not be made at the cost of stability or esthetics. In these patients, bimaxillary procedures are indicated.

Some authors consider indications of isolated BSSO to include the correction of horizontal mandibular deficiency and mandibular prognathism only ( Box 3-3 ).

-

Requires additional maxillary surgery for most dentofacial deformities

Mandibular Deficiency With Normal or Short Face

In patients with mandibular deficiency and short face, the mandible rotates upward and forward during growth, resulting in a relatively strong chin compared with the lower lip (see Case Report 3-2 ). On profile, the chin is often in good position, and the lower lip appears deficient. A tendency for the lower lip to curl has been noted. The shorter the face height, the greater is this tendency. The mandibular plane angle is usually low with a square gonial angle and well-developed masseter muscles. Most patients with short face have a deep bite problem—irritation of the gingival tissues in the labial lower gingiva or in the upper palatal gingiva. This depends on dental compensation. Lingual retracted upper incisors cause traumatic irritation of lower labial tissue, and deep bite with normal inclination or protrusion of upper incisors causes irritation of the upper palatal gingiva ( Box 3-4 ).

-

Normal or short anterior face height

-

Anterior deep bite

-

Proclined or reclined upper incisors

-

Increased overjet if not compensated by retrusion of the upper incisors

-

Tendency to develop a deep labiomental fold

-

Well-developed chin button

Many patients with short face and deep bite express TMJ noises such as clicking or popping. Discussion about the cause of this is controversial. Excessive distal positioning of condyles is one possible explanation ; unstable occlusal conditions as a “Sunday bite” (protruding the mandible to achieve a better interincisal relationship) have also been suggested as a predisposing factor.

BSSO is still the procedure of choice for lengthening a deficient mandible.

Mandibular Deficiency With Long Face

Mandibular deficiency combined with increased lower face height has two major components: increased maxillary vertical dimension and excessive chin height, both of which might be present in the same patient. In most patients, the main cause is rotation of the posterior palatal plane downward, which causes downward and posterior rotation of the mandible as well. The consequence is that class I dental relationship becomes class II, whereas class III dental relationship becomes class I. Therefore, excessive lower face height makes anterior-posterior (AP) mandibular deficiency worse.

The treatment plan in patients with mandibular deficiency and long face depends on the cause of the deformity. Isolated advancement of the mandible is indicated only when increased mandibular length is the result of excessive chin height (see Case Report 3-3 ). Increased maxillary vertical height must be corrected in the maxilla as well ( Box 3-5 ).

-

Excessive anterior face height, mainly in the lower third

-

Class I or II dental relationship

-

Normal overbite or open bite tendency

-

Possible narrow maxilla with crossbite posterior

-

Increasing lip incompetence with increasing face height

-

Incisor crowding in the lower jaw as down-rotation of the mandible makes the lower incisors tip back

-

Convex profile

MANDIBULAR PROGNATHISM

Mandibular prognathism is a condition wherein the mandibular arch is farther protruded with respect to the maxillary arch. In the NHANES study (1989-1994), 0.3% of the population in the United States was reported to have mandibular prognathism severe enough to require orthodontic-surgical treatment. About 14% of youth in the United States have a class III dental relationship. In 75-80%, this condition represents a combination of maxillary deficiency and mandibular protrusion. Only 20-25% of those individuals have isolated mandibular prognathism. This is not as common as mandibular deficiency, but a higher proportion of those with mandibular prognathism are handicapped in function and esthetics and require surgical-orthodontic treatment. Whereas only 5% of patients with mandibular deficiency seek surgical orthodontic treatment, about 30% of those with mandibular prognathism are surgical candidates. No reliable data for Europeans have been generated.

The term mandibular excess has its historical roots in the 10th century, when members of the Austrian Royal Habsburg family showed mandibular prognathism prevalent enough to become known as Habsburg jaw. The condition is colloquially referred to as Habsburg jaw, Habsburg lip, or Austrian lip. As a result of political intermarriages between Habsburgs, this trait was passed on by inbreeding. Charles II of Spain (“The Bewitched”) is said to have had the most pronounced Habsburg jaw and was even unable to chew (he frequently drooled and could barely be understood because of his large tongue) ( Figures 3-9 through 3-11 ; Rudolf I, Karl V, Charles II).

Esthetics is often unacceptable in severe mandibular prognathism; therefore, patients are likely to seek surgical treatment at a younger age. Surgery performed to correct the mandible was first performed in patients with mandibular prognathism for two reasons: (1) because it was recognized early on that mandibular prognathism or skeletal class III malocclusion could not be corrected by orthodontic treatment alone, and (2) because patients often were handicapped by functional problems such as chewing or speaking ( Box 3-6 ).

-

Mandible is more protruded compared with the maxilla

-

Prominent lower third of the face

-

Mandibular plane steep (especially when excessive anterior face height is present) or parallel to the palatal plane

-

Obtuse gonial plane

-

Anterior crossbite

-

Possible open bite

-

Concave or straight profile

-

Diminished or absent labiomental fold

-

Acute nasolabial angle

Mandibular setback by BSSO was the preferred procedure for shortening the mandible until the mid 1980s. The surgical objective in correcting mandibular prognathism is to shorten the mandibular body. Nevertheless, it is now evident that correcting this deformity with mandibular surgery alone might cause considerable problems. Patients with mandibular prognathism have a large tongue. Shortening the mandibular body by bringing the mandible back reduces the volume of the oral cavity and leaves less space for the tongue. The tongue is repositioned downward by physiologic adaptation. This produces increased pressure on the mandible post surgery and might increase the risk of relapse. In addition, the farther the mandible is moved back, the greater is the risk that a double chin will be created. Therefore, by the late 1990s, two-jaw surgery to correct mandibular prognathism was performed more frequently.

Mandibular Prognathism With Short Face

Mandibular prognathism and reduced anterior face height often result from the combination of reduced maxillary growth (most often three dimensional) and progressive mandibular growth. Maxillary deficiency enhances the anterior-posterior relationship in class III patients and makes the chin button more prominent. As a consequence of diagnosis, more than two thirds of class III patients are treated by means of bimaxillary surgery ( Box 3-7 and Figure 3-12 ).

-

Flat appearance of middle face

-

Mandible is more protruded compared with the maxilla

-

Low mandibular plane angle

-

-

Concave profile

-

Obtuse gonial plane

-

Diminished or absent labiomental fold

-

Acute nasolabial angle

-

Anterior crossbite

-

Many patients present with a thin lower lip, a reduced labiomental fold, and an acute nasolabial angle. Deficient zygomatic, paranasal, and infraorbital areas mainly cause a flat appearance on a frontal facial view, because most class III patients with short face present with a combination of mandibular excess and maxillary deficiency. Because the cause of the malocclusion is a combination of maxillary vertical (and sagittal) deficiency and mandibular excess, two-jaw surgery is indicated.

Mandibular Prognathism With Long Face

Inferior rotation of the posterior maxilla is the primary component in long face patients. The palatal plane rotates down, causing downward and backward rotation of the mandible. Dental class III patients become class I. Therefore, excessive facial height makes anterior-posterior mandibular prognathism better. Severe class III malocclusion is usually the result of excessive mandibular growth, which often is accentuated by reduced vertical maxillary growth. Maxillary deficiency increases the prominence of the chin, and the mandible rotates upward and forward. Although the lower lip–chin distance is great, these (adult) patients lack lip incompetence, in contrast to patients with mandibular deficiency and long face ( Figure 3-13 ). In those with mandibular prognathism, bone grows more and longer as does soft tissue. Isolated setback of the mandible is rare because both jaws most likely are involved in skeletal discrepancy ( Box 3-8 ).

-

Prominent lower third of the face

-

Steep mandibular plane angle

-

Obtuse or high gonial plane

-

Anterior crossbite

-

Possible open bite

MANDIBULAR ASYMMETRY

Asymmetric mandible can result from excessive mandibular growth or from deficient mandibular growth. Excessive growth on one side of the mandible leads to hemimandibular elongation or hemimandibular hypertrophy, depending on which parts of the mandible are involved. Hemimandibular elongation is caused by rapid enlargement mainly of the mandibular body ( Figure 3-14 ). It starts during puberty or shortly thereafter, and because growth is rapid, the maxilla is not involved.

Hemimandibular hyperplasia is characterized by diffuse enlargement of the condyle, the condylar neck, the ramus, and the body of the mandible ( Figure 3-15 ); because the anomaly begins before puberty and develops slowly, it is understandable that maxillary growth follows growth of the mandible ( Table 3-1 ). Therefore, BSSO without simultaneous correction of the maxilla leads to unstable and unesthetic results. Bimaxillary surgery is indicated in these patients. Both growth anomalies occur in pure and mixed forms. Most facial asymmetries are corrected by means of bimaxillary surgery. However, some mild discrepancy can be treated with mandibular surgery in combination with inferior border osteotomy ( Case Report 3-4 ).

| Hemimandibular Hypertrophy | Elongation | |

|---|---|---|

| Condyle | Diffuse, enlarged | Height is enlarged but normal form |

| Neck | Diffuse, enlarged | Enlarged height, but normal form |

| Ramus | Diffuse, enlarged | Normal |

| Body | Enlarged, sharp demarcation line and angle in the middle |

|

| Angle | Deeper on affected side | Normal |

| Chin | Deviated only slightly | Deviated to non-affected side |

| Teeth | Tipped to non-affected side | Normal, straight |

| Occlusal plane | Tipped, as ascending ramus is longer than non-affected side | Normal, as ascending ramus has normal length |

| Midline | Only slightly deviated to non- affected side (demarcation line) | Deviated to non-affected side |

| Bite | no crossbite sometimes open bite |

|

| Face | Looks “rotated” |

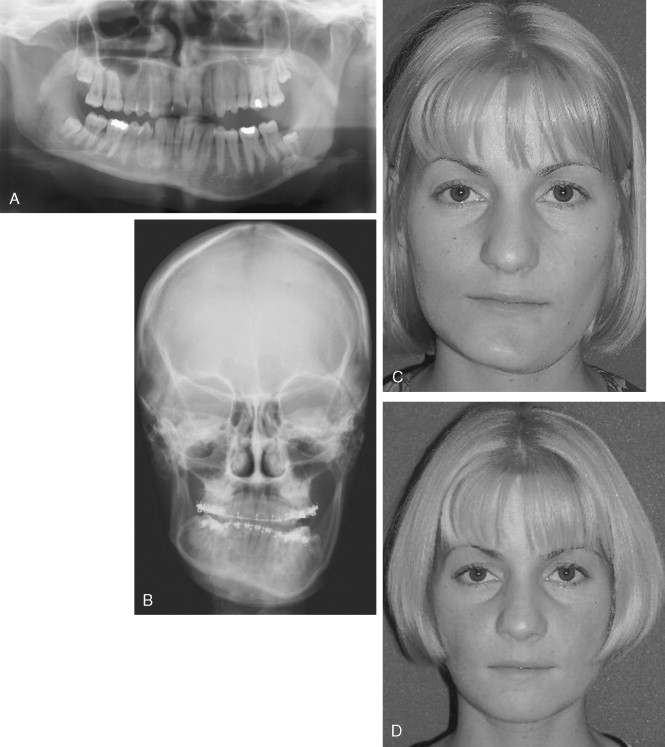

G.G., age 27, was seeking surgical orthodontic treatment because of facial asymmetry. Clinical examination revealed deviation of the lower jaw to the left side ( Figures 3-16 and 3-17 ). The chin was deviated 12 mm to the left, nonaffected side. The dental midline was deviated one and a half incisors to the left side. The patient said that this had started 2 years ago and had become worse since that time. He was very uncomfortable, and chewing was difficult; clicking of both TMJs had become worse. A control 99Tc scan performed prior to surgery showed no activity.

Treatment plan for this patient included BSSO to shift the mandible to the right side and a lower border osteotomy to reposition the chin.

INDICATIONS FOR BILATERAL SAGITTAL SPLIT OSTEOTOMY

Since its introduction in 1956, bilateral sagittal split osteotomy has become the most widely used surgical procedure for correction of malposition of the mandible. It has been modified in many ways, but for longer than 50 years, benefits and advantages of the procedure have remained unchanged ( Box 3-1 ).

-

Great three-dimensional flexibility in repositioning the distal fragments which allows accurate intraoperative positioning of the fragments

-

Broad bony overlap of osteotomized segments which results in excellent healing

-

Minimal alteration of the natural position of muscles of mastication which prevents relapse from muscular traction

-

Minimal alteration of the original position of the temporomandibular joint which minimizes the risk of postoperative athropathy

-

Short operating time and low complication rate

The design of the surgical cut as proposed by Obwegeser and the various modifications as proposed by a number of surgeons are especially effective for all surgical corrections of mandibular deformity.

The versatility of the procedure allows wide application in both mandibular advancement and mandibular setback. It tremendously increases the range of possible movements compared with orthodontic treatment alone, as demonstrated by Proffit’s envelope of discrepancy. The broad bony overlaps of the separated fragments allow not only advancement or setback of the distal tooth-baring mandible, but also rotations. Even with wide movements, bony interfaces are sufficient to allow excellent healing. Muscles of mastication stay attached to the proximal segment at the gonial angle. With rigid fixation from an intraoral approach, little detachment of muscles is necessary. This technique results in very little muscle traction, a condition that helps to prevent long-term relapse. Because the muscles of mastication stay attached to bone, it is easier to position the condyle during osteosynthesis. Correct positioning of the condyle is required if postoperative arthropathy is to be avoided.

The surgical procedure itself is a standardized method that helps to minimize the risk of complications and that shortens operating time.

MANDIBULAR DEFICIENCY

Mandibular deficiency is the most common dentofacial deformity that requires surgical orthodontic treatment. In the National Health And Nutrition Estimates Survey (1989-1994; NHANES III), about 2% of the adult population in the United States reported that they had deviations from the ideal bite that were severe enough to be handicapping. The prevalence of severe class II malocclusion (>6 mm overbite) was found to be 4.3% among those aged 18 to 50 years, and only 0.3% of the population had severe class III malocclusion (>3 mm overjet) that required surgical orthodontic treatment ( Box 3-2 ).

-

Increased A/B difference

-

Class II canine and molar relationship

-

Increased overjet if not compensated by retrusion of the upper incisors

-

Excessive curve of Spee in the mandible, sometimes combined with reduced curve of Spee in the maxilla

-

Incisor crowding, more often in the upper jaw than in the lower jaw

-

Tendency to develop a deep labiomental fold

The term mandibular deficiency solely reflects the anatomic position of the mandible in relation to the maxilla. The sagittal discrepancy between maxilla and mandible caused by underdevelopment of the mandible results in a class II dental relationship. This posterior movement in the horizontal axis during growth may go along with changes in the vertical axis, resulting in an increase or decrease in frontal facial height ( Case Reports 3-1 through 3-3 ).

R.J. was referred for orthodontic treatment at age 12. She presented with class II malocclusion and severe crowding in the lower arch. She wanted her teeth fixed and hadn’t liked her teeth for as long as she could remember ( Figure 3-2 through 3-4 ).

Oral health was good, and some bone loss was evident at the right medial lower incisor. R.J. had some clicking in the right joint and occasional pain.

On clinical examination of the face, AP mandibular deficiency was noted. Combined orthodontic-surgical treatment was suggested. Her parents believed she was too young for surgery at this point. Because of the joint pain, splint therapy was suggested. Orthodontic treatment was started when R.J. was 15 years old. Cephalometric analysis confirmed AP mandibular deficiency. At that time, bone loss at both of the medial lower incisors had worsened.

The treatment plan was as follows: To align the crowded lower arch, the left lower medial incisor had to be extracted; because some bone loss was apparent and all other teeth were in good health without caries, BSSO to advance the mandible was recommended.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses