INTRODUCTION

Cleft lip, with or without involvement of the palate, is a common malformation affecting approximately 1 in 700 live births in North America. When a cleft involves at least the lip and alveolus (primary palate), a complex, three-dimensional (3D) malformation is the result. Distortions of the skin, underlying musculature, mucosal membranes, underlying skeletal structures, and dentition are present. The goals of unilateral cleft lip and nasal repair include the creation of an intact upper lip with adequate vertical length and symmetry, repair of the underlying muscular structures with normal function, and primary correction of the associated nasal deformity. Posnick has described the surgical objectives of unilateral cleft lip repair as “the creation of a structure directly adjacent to its mirror image located in the most conspicuous are of the human body.”

The first techniques used for the repair of unilateral cleft lip primarily involved a straight line closure of the defect. Modifications involving the use of a quadrangular flap offered advantages over these initial techniques. The Tennison technique was described in 1952 and involved the use of a triangular flap and vertical repositioning of the Cupid’s bow area. Millard subsequently described the rotation and advancement flap technique, which is recognized as the most important technical development in the repair of the unilateral cleft lip and nasal deformity. Today most surgeons in North America and throughout the world use the Millard technique or some close modification of it.

Every cleft surgeon has a favorite technique for the repair of a unilateral cleft lip. In Parts I, II, and III of this chapter, experienced cleft surgeons provide an overview of three popular approaches used in the contemporary surgical treatment of unilateral cleft lip malformations: (1) the rotation and advancement flap technique, (2) the Tennison triangular flap repair technique, and (3) the functional approach to cleft lip repair.

TIMING OF CLEFT LIP REPAIR

Early protocols describing the staged reconstructive approach to cleft lip and palate deformities referred to the “rule of tens” as a general guideline for the exact timing of the initial lip repair. Surgery was delayed until the child was at least 10 weeks of age, weighed at least 10 pounds, and had a hemoglobin level of at least 10 g/dL. These guidelines initially were designed to minimize anesthetic morbidity and mortality in infants. Although contemporary anesthesia practices and pharmacologic agents would safely allow earlier surgery, cleft lip repair during the early neonatal period rarely is undertaken because no measurable benefit exists to performing lip repair before the infant is 10 to 12 weeks old. Today most North American cleft lip and palate programs continue to delay the initial surgery for cleft lip repair until the child is 10 to 12 weeks of age. This largely is because the hoped-for advantages of early lip repair have not been scientifically proven or documented in the world surgical literature. Proponents of surgery during the neonatal period often have referenced the “scar-less” healing associated with fetal development, with the idea being that if surgery is undertaken early in the neonatal period, then “fetal-like” physiology may still be present and the child will have less scar formation at the surgical site. Unfortunately, these benefits have not been observed, and problems with excessive scarring and less-favorable outcomes have been encountered. Neonates may have more scarring at this early age, and their tissues are smaller and more difficult to manipulate. Another potential rationale for early surgery is the psychosocial benefit of immediate repair. Again, scientific evaluations have failed to establish any psychosocial benefit or improved bonding between the mother and child as a result of early cleft lip repair.

TIMING OF CLEFT LIP REPAIR

Early protocols describing the staged reconstructive approach to cleft lip and palate deformities referred to the “rule of tens” as a general guideline for the exact timing of the initial lip repair. Surgery was delayed until the child was at least 10 weeks of age, weighed at least 10 pounds, and had a hemoglobin level of at least 10 g/dL. These guidelines initially were designed to minimize anesthetic morbidity and mortality in infants. Although contemporary anesthesia practices and pharmacologic agents would safely allow earlier surgery, cleft lip repair during the early neonatal period rarely is undertaken because no measurable benefit exists to performing lip repair before the infant is 10 to 12 weeks old. Today most North American cleft lip and palate programs continue to delay the initial surgery for cleft lip repair until the child is 10 to 12 weeks of age. This largely is because the hoped-for advantages of early lip repair have not been scientifically proven or documented in the world surgical literature. Proponents of surgery during the neonatal period often have referenced the “scar-less” healing associated with fetal development, with the idea being that if surgery is undertaken early in the neonatal period, then “fetal-like” physiology may still be present and the child will have less scar formation at the surgical site. Unfortunately, these benefits have not been observed, and problems with excessive scarring and less-favorable outcomes have been encountered. Neonates may have more scarring at this early age, and their tissues are smaller and more difficult to manipulate. Another potential rationale for early surgery is the psychosocial benefit of immediate repair. Again, scientific evaluations have failed to establish any psychosocial benefit or improved bonding between the mother and child as a result of early cleft lip repair.

DESCRIPTON AND COMPARISON OF SURGICAL TECHNIQUES

ROTATION AND ADVANCEMENT FLAP TECHNIQUE

A key technical component of the rotation and advancement flap technique described by Millard is the creation of a horizontal, back-cut incision within the superior region of the lip near the base of the columella. This allows downward rotation of the central lip to create adequate lip length and provides the needed downward rotation of the Cupid’s bow region. The Tennison procedure, in contrast, allows downward repositioning of the lower third of the lip and Cupid’s bow.

When the vertical lip incision and horizontal back cut are carried out, a segment of skin along the base of the columella is created and referred to as the C-flap. This C-flap is a portion of excess skin within the medial superior lip/prolabial area that can be used as part of the nasal sill repair or incorporated into the medial lip segment to create additional length.

The advancement flap refers to the lateral lip segment that is advanced into the defect during the repair. The lateral lip segment is prepared by creating a vertical incision with excision of hypoplastic tissue and identification of the orbicularis muscle, undermining of the overlying skin, and creation of releasing incisions within the maxillary vestibule. In addition, a horizontal incision along the alar base allows adequate mobilization so that the leading edge of the flap is advanced for closure of the defect.

Repair of a unilateral cleft lip and nasal deformity with a rotation and advancement flap technique involves the rotation of the medial lip segment downward, release of abnormal insertions involving muscular and cartilaginous structures, advancement of the lateral lip segment, and repair of the three tissue layers (mucosa, muscle, and skin). The popularity of the Millard rotation and advancement flap technique is a result of a number of distinct advantages, including the ability to normalize the position of Cupid’s bow and create lip length while positioning the vertical lip scar within the natural line of the philtral column. This approach uses all the prolabial skin to create adequate vertical dimension of the lip. The procedure may be applied to a wide spectrum of cleft malformations with consistent success. In addition, the rotation and advancement flap technique offers the surgeon significant flexibility so that intraoperative adjustments can be made.

Theoretical disadvantages of the rotation and advancement flap technique are most likely encountered in cases of wide cleft defects. One challenge is an insufficient lip length in cases of severe, complete cleft defects. Subsequent wound contracture along a vertical scar may shorten the lip further. Over the years, modifications and refinements to the original procedure have been made by Millard and others to address these potential problems.

TENNISON TRIANGULAR FLAP TECHNIQUE

Unlike the rotation and advancement flap technique described by Millard, the Tennison lip repair technique uses a back cut placed at the bottom of the central lip within the philtral skin along the white roll. The defect created in this region is then repaired with a full-thickness triangular flap elevated within the lateral lip segment. This incision placed along the inferior aspect of the philtral column allows downward movement of the Cupid’s bow but does not allow inferior displacement (i.e., vertical lengthening) of the entire lip segment to the same extent as the Millard procedure.

Compared with the Millard rotation and advancement flap procedure, the Tennison technique has a number of theoretic advantages. The procedure allows a significant amount of vertical repositioning of the Cupid’s bow with a relatively easy maneuver (horizontal incision parallel to the white roll). Proponents of the procedure also argue that the triangular design avoids the problem of wound contracture and lip length shortening encountered with the vertical philtral column scar seen in the rotation and advancement flap operation. Lastly, the tendency to excise too much tissue along the nasal sill and end up with a smaller nostril on the cleft side is decreased with the Tennison procedure.

The most prominent criticism of the Tennison technique relates to the horizontal back cut along the white roll into the philtral column to allow downward rotation of the Cupid’s bow. The disadvantage is the placement of a horizontal incision and resultant scar across the philtrum. Surgeons who routinely use the Tennison procedure try to minimize the resultant scar by controlling how far the horizontal incision is extended across the philtrum. The idea is to extend the horizontal incision to the midline only and not to the contralateral philtral column. Another potential pitfall associated with the Tennison repair is the fact that it is more technique sensitive. Specifically, flaps are designed with calipers to measure incision lengths based on numerous anatomic landmarks. Once the flaps are elevated, little opportunity is available for change in design and, in fact, many surgeons describe a point of no return during the procedure in which little or no modification is possible. This stands in sharp contrast to the rotation and advancement flap technique, which allows intraoperative adjustments of the repair. In Part II, the author makes an excellent suggestion: to begin a Tennison repair by first developing all incisions and flaps on the medial aspect of the cleft defect. This allows the surgeon an opportunity to reevaluate the defect intraoperatively and create any final modifications in the lateral flap.

FUNCTIONAL CLEFT LIP REPAIR: THE DELAIRE PHILOSOPHY

The theory of a functional matrix that drives facial development is well described in the orthodontic and surgical literature. This concept is that the growth of dentofacial and skeletal components is shaped by the surrounding soft tissue (e.g., skin, muscle) matrices. This important developmental principle also is at the center of the functional cleft lip repair. Facial clefts disrupt functional muscular fields or musculoaponeurotic units during fetal development. These abnormally positioned soft tissue elements cause disruption of subsequent development of underlying skeletal and cartilaginous structures. In a cleft of the upper lip, specific muscle groups, including the orbicularis oris, transversalis nasi, levator labii superioris, alaeque nasi, zygomaticus, and levator anguli oris, are all involved by the cleft defect, are malpositioned, and have abnormal insertions within the surrounding bony anatomy. Over time, abnormal position and function affect form so that these abnormal muscle insertions and positions lead to a secondary hard tissue deformity.

In a series of publications, Delaire was the first to propose a surgical approach for the correction of cleft lip and palate centered around the proper anatomic repositioning of underlying musculature and aponeurotic attachments. Delaire described a system of several muscular sphincters or rings in relation to the nasal and oral structures. His work led to the philosophical approach that the cleft surgeon must reestablish the normal position of these muscular units that comprise the functional matrix of the face so that normal function and growth patterns are created. The idea is to reposition the muscle aponeurotic system and establish an equilibrium to the action of the nasolabial musculature. More recently, Carstens has elaborated on this functional matrix repair with particular emphasis on the embryologic origin of the soft tissue and muscular elements being repaired.

In practical terms, this philosophy of functional repair translates into key differences in the surgical procedure compared with the rotation and advancement flap and Tennison triangular flap procedures. First, subperiosteal dissection is used as part of the functional repair technique. Subperiosteal dissection allows aggressive mobilization of musculoaponeurotic elements and the lower lateral cartilages of the nasal complex. A theoretical advantage of subperiosteal dissection is that less disruption occurs to the blood supply of the muscles being reoriented. This concern for the meticulous preservation of blood supply also is carried over into the incision and flap designs used for functional repair. Surgeons carrying out functional repairs often avoid the use of back cuts across the skin of the columella base and eliminate or minimize horizontal incisions along the lateral alar base to avoid any degree of interruption in blood supply.

SUMMARY

The contemporary armamentarium of the cleft surgeon includes a number of surgical procedures and technical refinements that have evolved over the past 60 years. In the three parts that follow, specific attention is given to three popular treatment approaches used in the initial repair of the unilateral cleft lip and nasal malformation. The authors provide an overview of general principles and theoretic advantages and disadvantages. The first of these descriptions covers the Millard rotation and advancement flap technique, which remains the most popular procedure used for the repair of the unilateral cleft lip. Although less popular in the United States, the Tennison triangular flap technique frequently is used in cleft programs worldwide. The description of the Tennison procedure provides a concise review of the technique, an overview of the advantages of the procedure, and a number of clinical examples provided by a world authority on the subject. A review of functional cleft lip repair provides an overview of the philosophical principles advanced by Delaire for the creation of a normalized functional matrix during cleft lip repair. Common to all three approaches is an emphasis on the importance of careful incision design, adequate muscle repair, and attention to primary repair of the associated nasal deformity. The objective of this section of the text is to provide a review of these contemporary principles relevant to the reconstruction of cleft lip. A detailed understanding of a broad range of surgical techniques from which to choose ultimately will provide the cleft surgeon with the greatest likelihood for success.

Rotation and Advancement Flap Technique for Unilateral Cleft Lip Repair

- Kevin S. Smith

The asymmetry of the unilateral cleft lip and palate is a complex, multidimensional deformity. Refinements in the surgical approach for the reconstruction of this congenital defect have evolved over time. The rotation and advancement flap technique for cleft lip repair probably is the most widely used operative procedure for the unilateral cleft lip. This cleft lip repair technique was first introduced in 1955 by Millard. The markings and measurements used for the Millard rotation and advancement flap procedure are straightforward and allow the incorporation of intraoperative adjustments during the operation. With this “trim as you go” technique, superior results are routinely achieved.

The objectives of unilateral cleft lip repair include (1) approximation of cleft edges without loss of natural landmarks, (2) repositioning of the cupid’s bow into a normal position, (3) placement of incisions and scar along natural lines, (4) muscle repair and alignment, (5) balancing of the alar bases, and (6) an equal columella bilaterally. In combination, these goals address the asymmetry inherent with both incomplete and complete clefts involving the lip and primary palate. Specific components of orofacial cleft deformities involving the lip and alveolus (primary palate) include (1) a muscle continuity defect, (2) vertical deficiency of the lip on the affected side, (3) deficiency of the nasal structures on the ipsilateral side, (4) lower position of the dome of the nasal ala on the ipsilateral side, (5) possible short columella, and (6) an underlying skeletal deformity characterized by a dental crossbite and poor bony foundation on which the nasal labial structures rest.

Although the use of the Millard rotation and advancement flap technique yields consistently favorable results, some questions have been posed regarding its limitations when applied to wide, unilateral cleft lip defects. The specific potential pitfall when used in wide cleft defects is that the resultant lip repair is vertically short, with insufficient lateral lip vermilion. Modifications to the Millard technique have been made to address this problem better. These refinements have included inferior cutaneous flaps and the white roll flap, which is a small, triangular interdigitation just above the vermilion. These modifications were added because of observations by several surgeons that the rotation was inadequate and that significant whistle-type deformities occurred after basic Millard rotation advancement flap.

Another option in cases of wide cleft lip and palate defects is the use of a lip adhesion procedure as an initial phase of surgery. This is performed early during infancy, and the subsequent, definitive lip repair procedure with a rotation advancement technique is delayed for several months. The lip adhesion involves a simple two-layer (lip skin and mucosa) repair of the lip that converts a wide, complete defect into an incomplete, more-narrow defect over time. In addition to narrowing the cleft gap, a theoretical advantage of the adhesion procedure is the secondary molding of cleft maxillary segments into a more anatomically favorable position before final lip closure and/or palate repair. Some authors prefer the use of presurgical orthopedic devices, such as the Latham appliance, with or without a lip adhesion. This provides more aggressive repositioning of the skeletal elements in the hope of simplifying the lip repair surgery and maximizing esthetic results. Although the combination of a lip adhesion and Latham device makes the eventual lip repair more easily performed, a negative effect on subsequent midfacial growth often occurs. More recently, the use of nasoalveolar molding techniques has grown in popularity. Presurgical nasoalveolar molding is applied to improve the position of maxillary segments and idealize soft tissue contour and position before initial lip and nasal repair. The use of nasoalveolar molding in the cleft lip and palate patient is discussed in greater detail in Chapter 38 .

During the 1940s and 1950s, the late Dr. Oscar Asensio of the Hospital Centro Infantil de Estomatologia in Antigua, Guatemala, was simultaneously developing a technique involving a modification of the rotation and advancement flap procedure. Asensio’s operation for the repair of the unilateral cleft lip is significant in that it allows for the creation of significant vertical dimension while preserving lateral vermilion. Asensio, an oral and maxillofacial surgeon, described in English his technique for rotation and advancement flap at the American Association of Plastic Surgeons meeting on June 25, 1973. At that time he had operated on more than 548 clefts. In the years before that, Asensio was confronted with a significant number of wide cleft lip malformations not being repaired in Guatemala. His technique proved to be useful in cases in which patients had large defects and the adjuncts of lip adhesion and presurgical orthopedic appliances were not readily available. His son, Dr. Rodolfo Asensio, trained in pediatrics and oral and maxillofacial surgery, continues his father’s work in Antigua to this day. Together, both Asensios have repaired more than 3000 clefts. These procedures typically are performed under local anesthesia and sedation.

PRESURGICAL CARE

If nasoalveolar molding, lip taping, or pin-retained orthopedic (Latham) treatments are planned, they should be initiated during the second to fourth weeks of life. Impressions are made and used in the fabrication of the appliances. The preferred technique for lip taping is to use a type of occlusive wound care dressing on the skin so that the tape will not touch the skin. The dressing is applied with a skin adhesive, and any lip taping materials are then adhered to the dressing. This ensures minimal skin irritation of the infant during the taping procedures. As with the nasoalveolar molding and Latham-type devices, lip taping is time consuming and relies on compliant parents. Nasoalveolar molding can be accomplished in the wide unilateral cleft lip, and the author’s personal experience has revealed that this technique is simpler and less costly than the Latham-type appliance. Another benefit of nasoalveolar molding is that it does not appear to have the negative effect on midfacial growth observed with the use of the Latham device.

DESCRIPTION OF SURGICAL PROCEDURES

MILLARD ROTATION AND ADVANCEMENT FLAP TECHNIQUE

The rotation and advancement flap technique described by Millard is the most frequently used repair by cleft surgeons worldwide. Most surgeons add their own preferences and modifications to this technique depending on the specific cleft deformity (complete, incomplete, etc.) and individual patient’s anatomy.

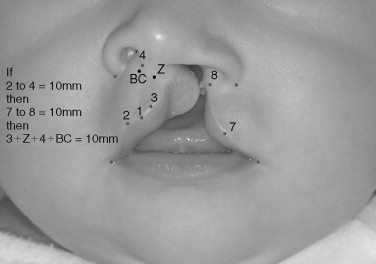

Figure 36-1 demonstrates the classic anatomic landmarks used in the Millard procedure. Those points are identified to make initial measurements and achieve anatomic alignment of specific soft tissue elements. To preserve maximal soft tissue, initial incisions are followed by paring of tissue elements as the procedure continues.

Three key technical principles of the Millard rotation and advancement flap procedure are as follows:

- 1.

The rotation of the cleft edge of the noncleft side is the most important principle to understand and perform to obtain adequate vertical height at the cleft philtral ridge. This is accomplished by the measurement between the base of the columella (point 4) and the Cupid’s bow on the noncleft side (point 2). This distance equals the total length of the incision made on the cleft edge of the noncleft segment, from point 3 to the base of columella (point Z) and including the back cut (BC). A bent wire is sometimes used to confirm this distance. The wire is used to represent this curvilinear incision with the back cut included ( Figure 36-2 ). Additional height can be obtained in the area of the cleft by making a white roll flap incision at the area of point 3. When used, this usually is a 1- to 2-mm incision to allow increased rotation of the vermilion segment.

FIGURE 36-2 Markings and measurements used for the Millard-type rotation and advancement flap cleft lip repair. Points 1, 2, and 3 represent the outline of Cupid’s bow. Point 4 represents the base of the columella. Point Z is the lateral base of the columella on the side of the cleft. Point BC represents the extent of the back cut. In measuring for a Millard-type closure, the distance from points 2 to 4 will equal the curvilinear cut that goes from points 3 to Z to 4 and then to BC. That total distance will also be equivalent to the measurement from points 7 to 8. - 2.

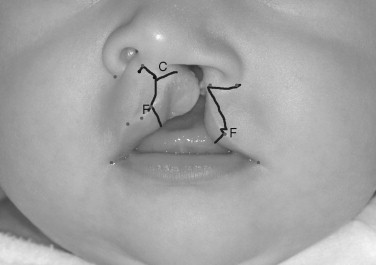

The vertical height of the lateral lip segment on the cleft side must be developed to a length equal to the rotation segment. If the distance between point 7 and point 8 is insufficient, tissue is pared away laterally in the area of point 8 to increase the vertical dimension until it equals the measured distance on the rotated side. If a white roll flap is to be used at the vermilion border, it should be developed when these cuts are made just above point 7 (area F in Figure 36-3 ). The final incisions are demonstrated in Figure 36-3 . The C-flap can be used to create a nasal floor repair or incorporated into the noncleft side to increase the amount of rotation and length.

FIGURE 36-3 The final incision design for the Millard-type rotation and advancement flap closure. The C-flap can be placed into the base of the columella or into the nasal sill region. F represents possible back cuts for additional lengthening with the use of a white roll flap above the vermilion border. - 3.

The third principle critical to the Millard procedure is that of muscle dissection and reconstruction. The orbicularis oris must be identified and isolated separately from the overlying skin and mucosa. The muscle should be freed several millimeters into the lip element on either side so that anastomosis of the lip muscle can be accomplished as a distinct layer of the repair ( Figure 36-4 ).

FIGURE 36-4 Intraoperative view of the lateral advancement flap dissection. The center forceps are holding the well-defined orbicularis oris muscle. Defining and joining the two sides of the muscle is of utmost importance in cleft repair. To view a color version of this illustration, refer to the color insert section at the back of this book.

Intraorally, closure of the wide cleft lip requires the vestibular incision on the cleft side; in wide clefts this incision occasionally must be extended superiorly into the nasal cavity, almost to the point of the inferior turbinate. This tissue has been undermined in the supraperiosteal plane to allow adequate advancement of tissue on the cleft side.

ASENSIO TECHNIQUE FOR ROTATION AND ADVANCEMENT FLAP

The general principles of this closure for unilateral cleft lip defects are quite similar to the Millard rotation and advancement flap technique. The primary modification made in the Asensio procedure involves the excision of a soft tissue segment from the lateral advancement flap to create additional length while preserving vermilion tissue. The Asensio technique is defined specifically by the initial measurements and markings and requires little refinement once the incisions have been made. Elements of the landmarks, markings, and surgical steps for the Asensio technique are as follows:

- 1.

Anatomic landmarks within the alar base, Cupid’s bow, and lip segments are marked on each side (see Figure 36-1 ) in identical fashion as for the Millard procedure. Landmarks are identified and key white roll points are marked. On the lateral side, the end of the distance from the white roll point at the leading edge of the advancement flap is measured to the commissure for comparison with the contralateral side.

- 2.

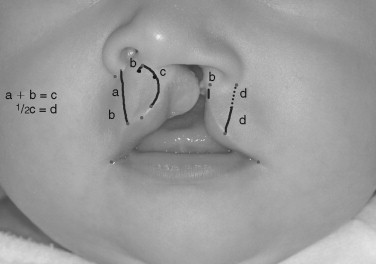

The distance of the height of the ala to the lip is now measured on the noncleft side. This distance is labeled distance a and is called the alar height. Add 1 to 3 mm to distance a depending on the size of the patient’s lip: 1 mm for an infant, 2 mm for a child, and 3 mm for an adult. This small additional measurement is referred to as distance b and is used to calculate the length of the back cut. Next, the addition of distances a and b equals the length of the incision labeled distance c in Figure 36-5 . Distance c is then measured in a curvilinear manner from the Cupid’s bow to the columella and marked. In addition, the distance b measurement is added for the back cut. These markings are similar to those used in a Mallard-type rotation advancement.

FIGURE 36-5 Measurements and markings for the Asensio technique. Rotation length is again determined by measuring the distance from the alar base to the white roll point on the noncleft lateral Cupid’s bow. Line b is the back cut distance and line c is equal to a ±1 b. One half of line c will become the distance of line d. - 3.

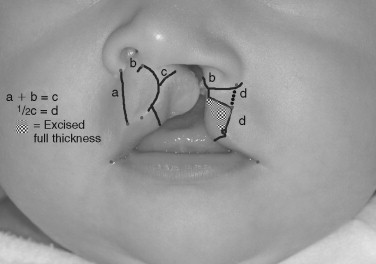

On the lateral lip element, distance of line c is then divided in half and used to calculate the length of a new incision line d. Putting one point of a compass at the previously marked alar base, an arc is swung using line d as the radius. After putting one point of the compass at the end of the white line, another arc is drawn using d (½ the length of c ) as the radius, where these arcs intersect ( Figure 36-5 ). This establishes the length of the lateral lip after the incisions are created. This ensures that the length of the lateral, advancing lip segment will match the length of the rotation side. After this point has been marked, the quadrilateral flap is drawn, with the width of the leading edge equal to the length of distance b, as illustrated in Figure 36-6 . The termination of the superior border of the quadrilateral flap goes to the outer edge of the ala. The lower edge of the quadrilateral flap goes to the point where the arcs met. Note that the area shaded in Figure 36-7 represents a full- thickness excision of the lateral lip advancement flap. If a white roll flap is to be used at the vermilion border, it can be developed during the final stages of the procedure.

FIGURE 36-6 The final incision design for the Asensio technique (excluding intranasal incisions). The patterned area is the area for full-thickness excision. White roll flaps can be included in the design if needed. Note line a is not an incision, but rather only one of the original measurements.

FIGURE 36-7 The final result of left complete cleft lip repair for the patient seen in Figure 36-6 , using an Asensio technique. The photograph was taken 1.5 years after surgery.

NASAL RESHAPING

In addition to rotation and advancement flap maneuvers and careful muscle reconstruction, cleft surgeons must address the abnormal position of the lower lateral nasal cartilages in the cleft patient. Once adequate mobilization of the advancement flap has been accomplished, mobilization of the nasal cartilages on the affected side must be performed to release cartilaginous structures from their abnormal attachments to the underlying piriform rim. McComb described lower lateral nasal cartilage lifting during initial cleft lip repair. The technique is relatively simple and involves careful dissection between the lower lateral cartilage and cutaneous elements. These structures may be approached through the columellar and lateral alar incisions. Once the cartilage has been thoroughly dissected free of the skin, intranasal splinting techniques can be used to hold the cartilages in a more normal anatomic position. The technique originally was described using bolsters and sutures and lifting the suture transcutaneously superiorly on the nose with another bolster on the skin.

The author’s preferred technique involves the use of silicone nasal formers. They are available in a multitude of sizes, can be sutured in place, and remain intact during the initial phase of postoperative healing. Care must be taken to observe for wound dehiscence and mucosal ulceration intranasally. The use of silicone nasal molding devices also requires extra care on the part of the family in that the devices need to be cleaned and irrigated on a regular basis with saline and a syringe with a catheter. Infants are obligate nasal breathers, so the nasal stents must be kept free of dried mucus and blood. Nursing staff and parents must understand the proper technique in cleaning these stents before discharge.

POSTOPERATIVE CARE

In addition to nasal bolsters or stents, a lip dressing is applied with skin adhesive lateral to the incisions and ¼-inch sterile tape as a simple coverage for the wound. This taping over the lip segments also provides support for the completed lip repair. If good muscle and subcutaneous closure have been accomplished, a Logan’s bow or other device is not necessary. The infant may need to have arm restraints postoperatively, but generally these can be discontinued at 2 weeks. At 1 week after surgery the nasal stents can be removed. The sterile tape dressing over the lip usually lasts 3 to 5 days or can be removed at the first postoperative visit 1 week after surgery. Any minor scabbing present can be removed with dilute hydrogen peroxide for daily wound care over the course of the next week. In addition petroleum jelly can be applied to the wound to help soften any scabbing.

At postoperative week 2, definitive wound care must begin. This wound care regimen can include massage with vitamin E oil with a two-finger technique, in which one finger is placed inside the lip and one finger is outside, as much as the infant can tolerate. Once the vitamin E oil has been massaged into the skin, a silicone gel material is placed over the wound. This is accomplished twice a day with gentle cleaning with mild baby soap before the massages. This twice-daily regimen should be continued for 4 months.

SUMMARY

The rotation and advancement flap technique remains the most popular surgical approach for the repair of the unilateral cleft lip deformity ( Figures 36-8 and 36-9

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses