After several years of observation and clinical practice, it became evident that a majority of patients placed their partial dentures in their mouth in one manner, regardless of how the cast had been surveyed. This was straight up and down. Odd paths of insertion often caused patients difficulty during insertion and removal. A more important observation was that many clasps, designed to gain retention from undercuts which had been created by tilting the cast, had no retention when they were placed in the mouth. These observations and the confusion surrounding surveying led to a simplified approach which has proved successful, both in the laboratory and in clinical practice.

RULES FOR SURVEYING

1.Undercuts cannot be produced or created by tilting a cast.

2.All casts are originally surveyed with the occlusal plane parallel to the base of the surveyor. (Zero degree tilt)

3.The retentive tips of clasps must engage undercuts which are present when the cast is surveyed in this position.

4.Wherever possible, undesirable undercuts and areas of interference are removed during mouth preparation by the dentist by recontouring teeth or making necessary restorations.

5.The cast may be tilted in the following instances:

(a)to equalize undercuts,

(b)to place a clasp tip in a better position for esthetics and

(c) where six anterior teeth remain which are at such an angle that the survey line is at the incisal edge of the teeth when the cast has a zero degree tilt. In each of these situations, however, it is necessary that the clasp tip be in an undercut which was present when the cast was surveyed in its parallel or zero degree tilt position. If the clasp tip is not in such an undercut, it will not be retentive when placed in the patient’s mouth.

This system of surveying is simple, easy to understand, and produces uniformly good results. It places the burden for successful partial dentures with the dentist, as it is necessary that he prepare the teeth so that the partial denture will function to its maximum effectiveness.

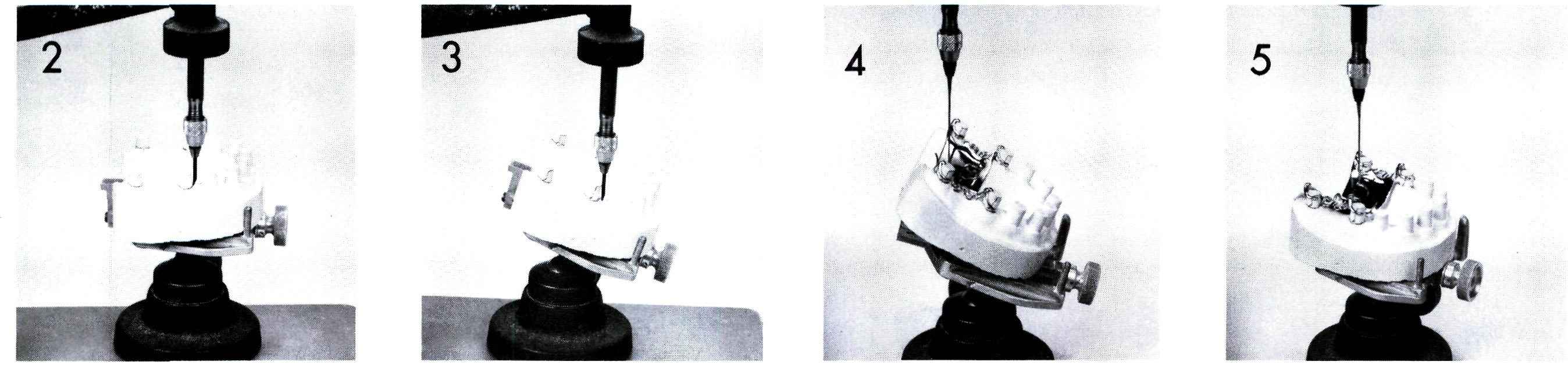

An illustration of the fallacy of “creating” or “producing” undercuts by tilting a cast is shown in Figures 2 through 5. A cast was made in which all of the teeth are represented by cones. It can be seen that there are no undercuts present when this cast is surveyed with the occlusal plane parallel to the base of the surveyor (Figure 2). It is seen also that undercuts are present when the cast is tilted (Figure 3). A partial denture, made so that the clasp tips engage these undercuts, is retentive as long as the cast is held in this position (Figure 4). However, when the cast is again parallel, and most mouths are in this position, the partial denture has no retention (Figure 5). It has been said facetiously that tilting a cast is valid if a patient holds his head at the same angle as the cast when it was surveyed.

CLASPS

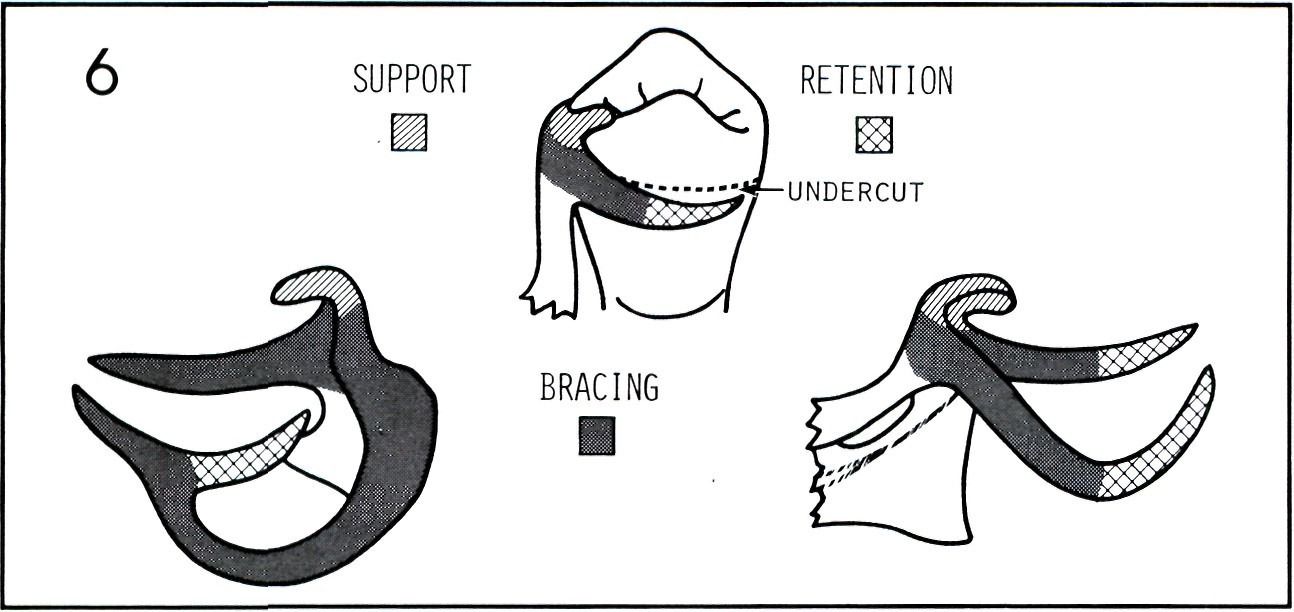

All properly constructed clasps have three functions: support, bracing, and retention (Figure 6). Support is achieved through one or more occlusal rests which rest on the occlusal surface of a tooth and are attached with a rigid connector to the appliance. Occlusal rests resist vertical forces and prevent the appliance from moving toward the tissue (settling) and causing injury to the soft tissues adjacent to the teeth. (Rests may be placed on the incisal edge or in prepared cinguli areas of anterior teeth.)

Bracing resists lateral forces and is achieved by the rigid portions of clasp arms contacting the lateral surfaces of a tooth.

Retention is derived from the flexible tips of the clasp arms. Retention resists forces tending to displace the appliance occlusally. Clasp retention is possible because the metal used in partial dentures is stiff and resists deformation. The tip of the clasp flexes during insertion so that it engages an undercut on an abutment tooth. Once the clasp is in position, it is passive and exerts no force on the tooth except when the partial denture is removed or when vertical displacing forces are encountered.

The amount of undercut which a clasp engages is determined by (a) the flexibility of the clasp arm, (b) the depth of the undercut, and (c) the amount of undercut utilized. Flexibility depends on (a) the metal used in the clasp, (b) the design of the clasp, (c) the cross-sectional shape, whether it is round or half-round, (d) whether it is wrought or cast, and (e) the length of the clasp arm. Gold has twice the modulus of elasticity and is thus twice as flexible as most non-precious partial denture alloys when the materials are compared in similar clasp situations. A gold clasp can engage twice the undercut to gain the same amount of retention as a similar clasp made of non-precious alloy. Conversely, a non-precious clasp may engage half the undercut used for gold with similar results. These factors must be considered in the design of all clasps.

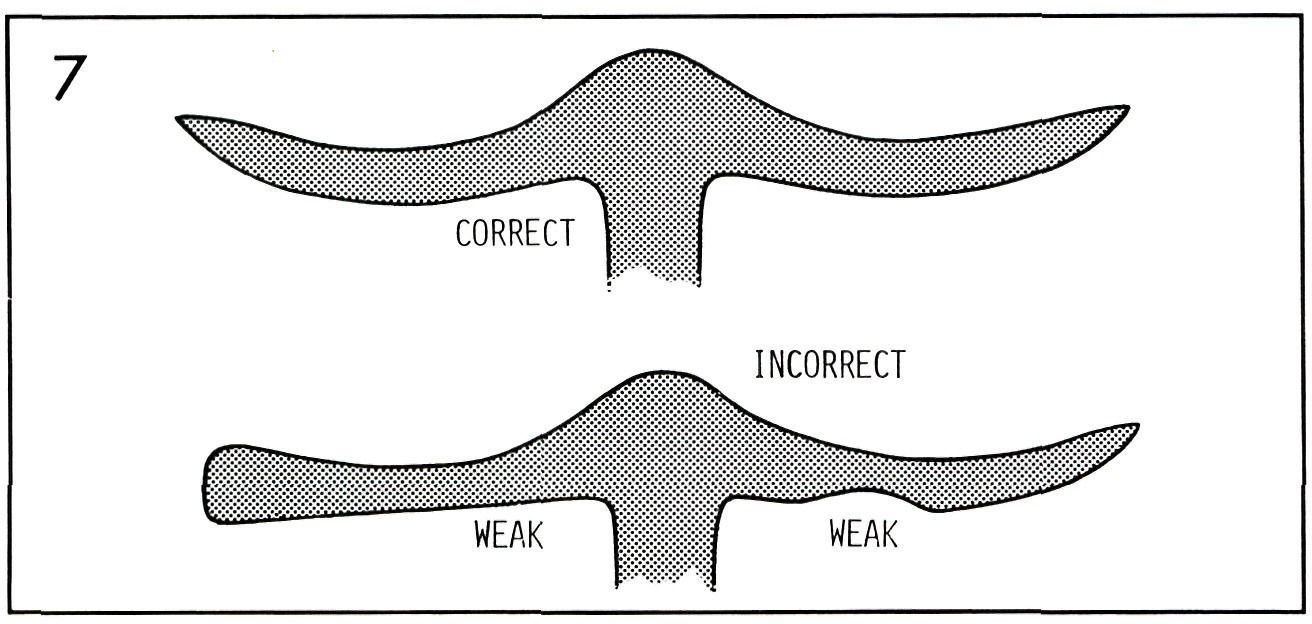

A clasp arm must taper from its origin to its tip (Figure 7). Clasp arms which taper uniformly flex uniformly. Breakage, distortion and inadequate retention may result when thin areas occur in a clasp arm.

There are three basic types of clasps, circumferential, bar, and wrought wire. Circumferential type clasps approach the undercut from an occlusal direction. Bar clasps approach the tooth from the gingival portion of the tooth after crossing soft tissue adjacent to the tooth. Wrought wire clasps are of circumferential design, but differ in the material from which they are made. The chief advantage of round wrought wire clasps is that they flex both vertically and horizontally, whereas cast clasps flex only in a horizontal manner.

There are two basic principles to be followed in designing clasps: (1) the clasp should not traumatize the tooth during insertion and removal, and (2) in free-end extension partial dentures the clasp should not cause the tooth to move when the partial denture moves under function. (There are fewer limitations on clasp design in tooth-borne partial dentures than in free-end extension partial dentures.)

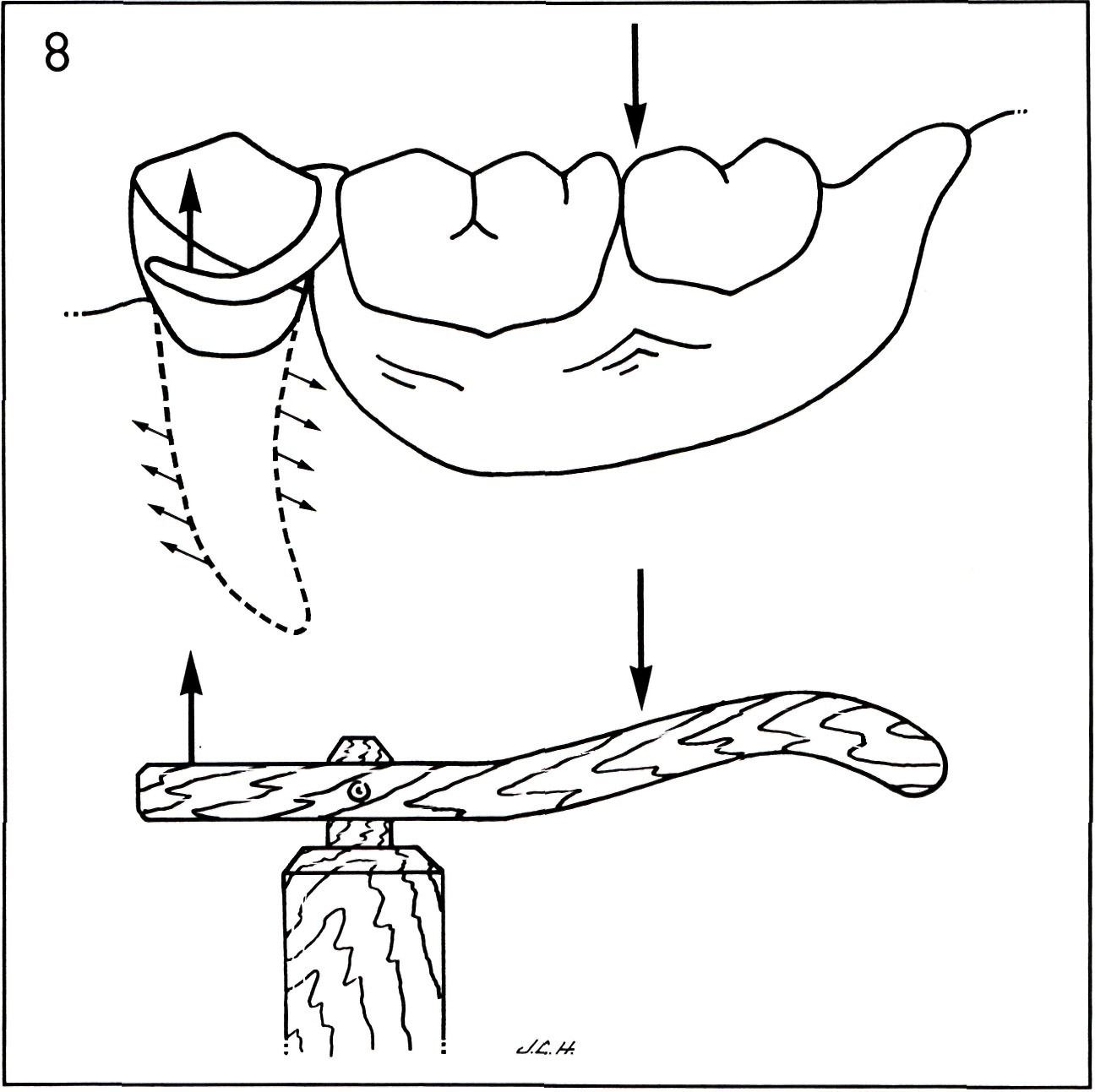

A free-end extension partial denture will act as mild extraction forceps if a rigid, nonyielding clasp is used on an abutment tooth. The action is very much like that of a pump handle (Figure 8). For this reason the clasp must be designed so that it can move on the tooth without moving the tooth when the partial is in function. This is done usually by utilizing an undercut adjacent to the edentulous area, a flexible clasp, and may be enhanced by using a mesial rest for better mechanical advantage.

Clasps with two arms may be designed so that both tips are retentive; i.e., engage undercuts. However, it is best to design clasps so that there is one retentive arm and one reciprocal arm. This prevents a clasp from being too retentive and injuring an abutment tooth. The reciprocal arm engages no undercut and opposes any force arising from the retentive clasp. Ideally, both retentive and reciprocal arms should be opposite each other and at the same level on the tooth, and the tooth surfaces contacted by minor connectors and reciprocal arms should be mutually parallel to prevent tooth movement during insertion and removal. This is often impossible or impractical to achieve. Paralleling these surfaces is the responsibility of the dentist and should be done when the mouth is being prepared.

The clasps most commonly used in partial denture construction are listed in atlas form on the following pages. An understanding of these clasps will enable an individual to design partial dentures for most mouths. Components of different clasps may be combined for unusual situations on condition that each clasp provides support, bracing and retention. It must be remembered that any clasp functions more effectively when the mouth has been well prepared by the dentist.

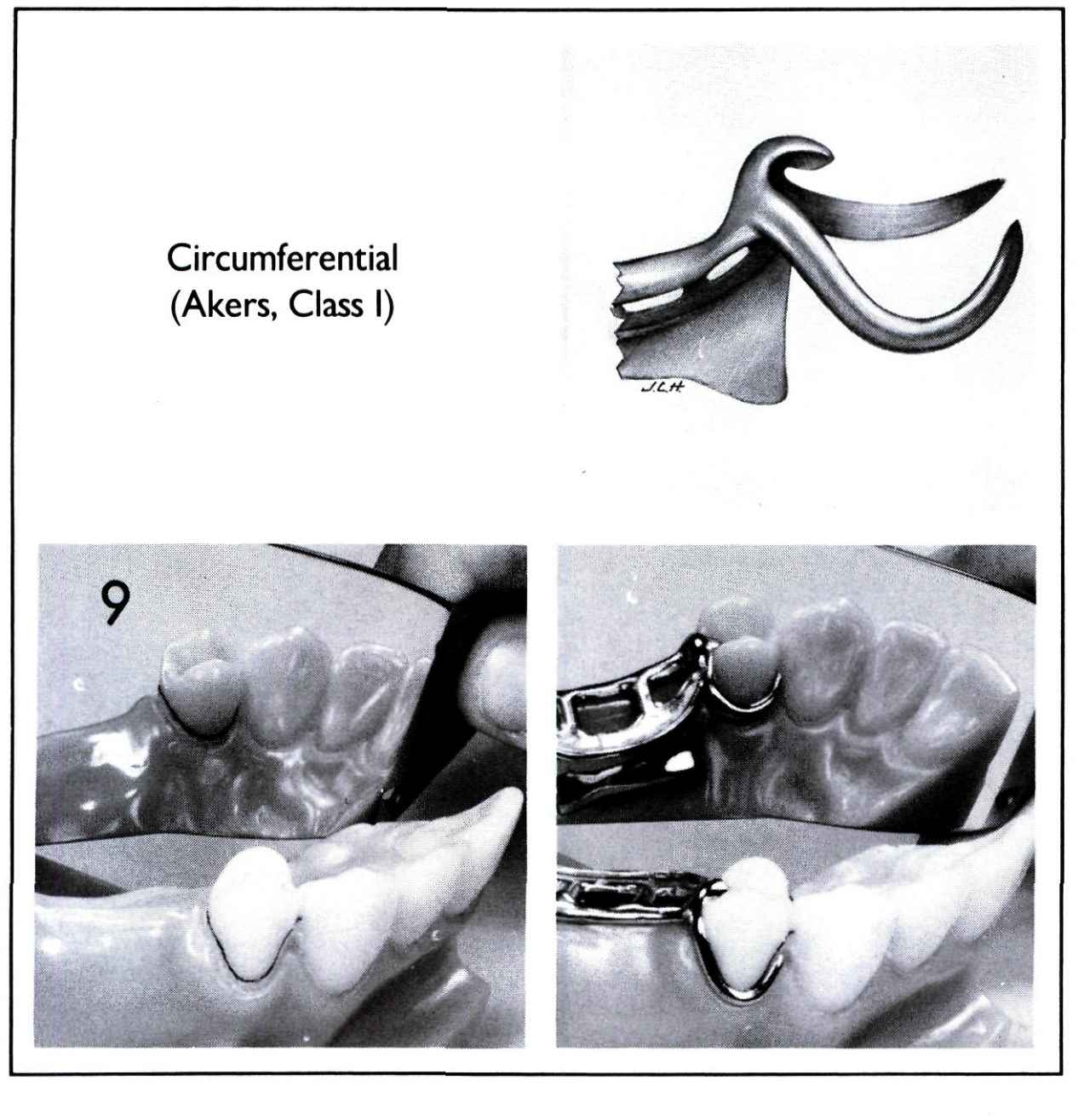

Type: Circumferential

Undercut Utilized: Mesiofacial and/or mesiolingual (.010–.020).

Indications:

1. Removable bridge (tooth borne partial) where there is no movement during function.

2. On free-end extensions where undercut is so small that longer clasp arms will not be retentive.

3. On free-end extensions when minimal undercut is utilized.

Contra – indications:

On free-end extensions except as noted above.

Advantages:

1. Good support and bracing, simple design.

2. Does not distort easily.

3. Easy to adjust.

4. Contacts minimal area of the tooth.

5. Good esthetics.

Disadvantages:

May traumatize abutments when used incorrectly on free-end extensions.

Comment:

Good clasp. May be used on any tooth with proper survey lines. Incorrect use results in slow painless extraction of abutment.

Type: Circumferential

Undercut Utilized:

1. Mesiofacial (.010) and distal (.010).

2. Mesiofacial only (.010–.020).

Indications:

1. Premolar and canine abutments on free-end extensions.

2. On anterior abutments of removable bridges when prognosis of posterior abutment is poor.

3. On short teeth with small mesiofacial and distal undercuts.

Contra-indications:

Not used on molars because of length of clasp arm.

Advantages:

1. Can use small undercut areas.

2. Length of clasp produces resiliency and “stress-breaking” effect on abutments for free-end extension partial dentures.

Disadvantages:

1. Easily distorted because of length. Difficult to adjust.

2. Large tooth area covered.

3. Bracing (resistance to lateral stress) only average.

4. Design produces “food trap” between lingual arm and major connector.

Comment:

“Stress-breaking” action dependent on creation of space between clasp and saddle to permit clasp to flex.

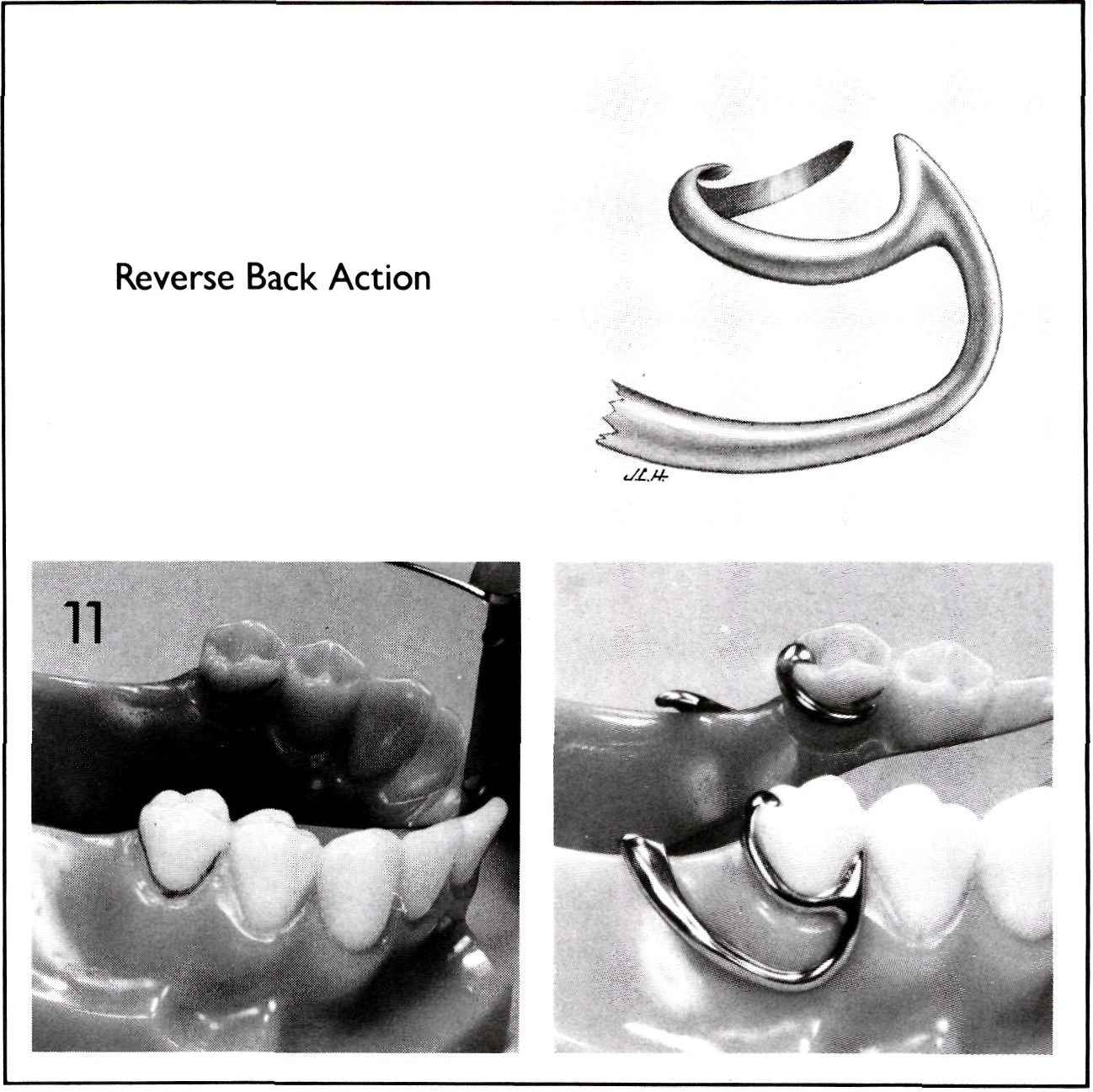

Type: Circumferential

Undercut Utilized:

1. Mesiolingual (.010) and distal (.010).

2. Mesiolingual only (.010–.020).

Indications:

Premolar abutments with lingual inclination on free-end extension partial dentures.

Contra – indications:

1. Maxillary partial dentures for esthetic reasons.

2. When there is a severe soft-tissue undercut inferior to lingual marginal gingiva.

Advantages:

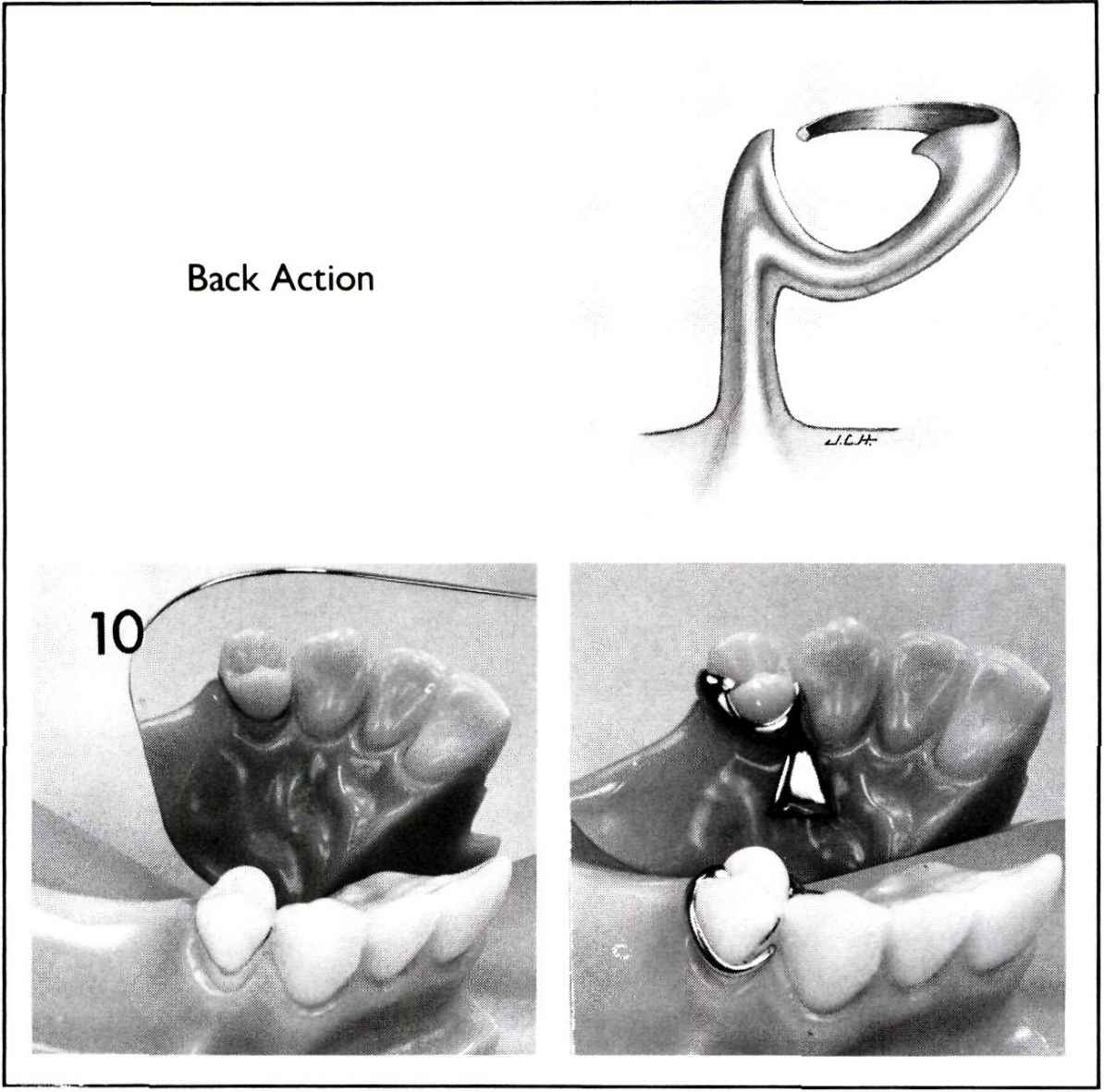

Has “stress-breaking” action similar to “back action clasp.”

Disadvantages:

1. Crosses soft tissue.

2. Excessively long clasp, easily distorted, difficult to adjust.

3. Poor esthetics.

4. Contacts large area of tooth.

Comment:

This clasp is a combination of a bar clasp and a back action clasp with none of their advantages and all of their disadvantages. It should be avoided whenever possible.

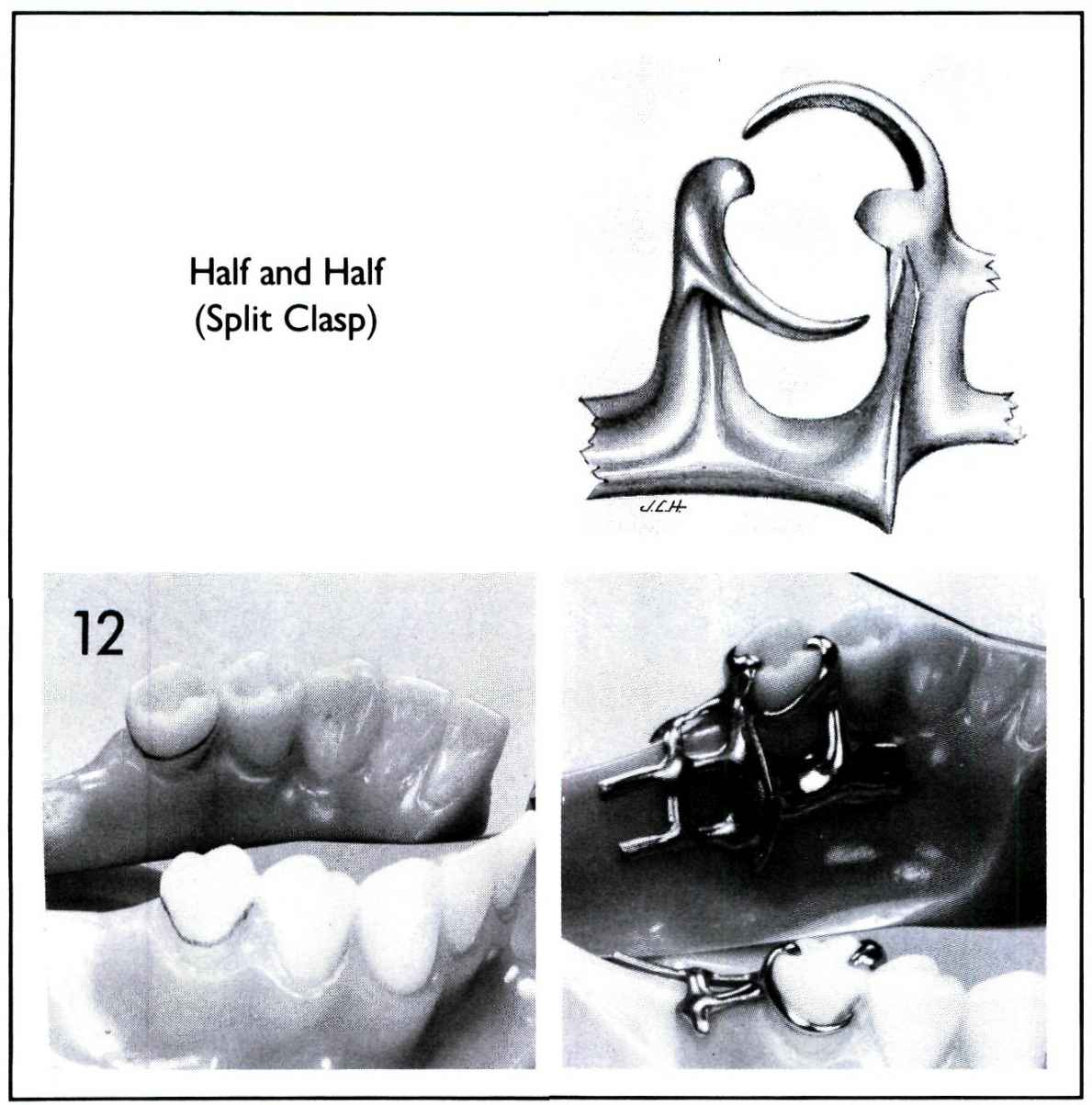

Type: Circumferential

Undercut Utilized: Distolingual (.010).

Indications:

1. Premolar and molar abutments for free-end extension partial dentures and removable bridges.

2. Isolated teeth when they cannot be made contiguous with the dental arch by means of a fixed restoration, often for bracing only, with no undercut engaged.

Contra – indications:

None. May be used to avoid trauma to abutment on free-end extension partial dentures.

Advantages:

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses