41 Quality of Life in Salivary Gland Diseases

Challenges in Assessing Quality of Life

Specific Problems in Salivary Gland Diseases

Malignant Salivary Gland Tumors

Measures to Improve Quality of Life

Introduction

Mr. Smith and his wife come to our psychosocial counseling center for cancer patients. He is moving slowly, and his body is so thin that his trousers nearly slip off. It is obvious that this is a cancer patient who does not have very much time left. The couple sit down and before they begin to speak, his wife hands him a plastic bag, which he uses to put his thick, sticky saliva into. He is unable to swallow it because it is too viscous and he doesn’t have enough energy. It takes a while for him to empty his mouth. Then he starts crying and says how humiliated he feels because of this scene.

In everyday life, most people do not notice the importance of their saliva. Swallowing, eating, tasting, speaking, kissing, the health of the teeth – all of these are involved in our quality of life, with saliva playing an important part in them. When salivation is reduced or excessive, the physical and emotional suffering that results can be immense.

This chapter defines and conceptualizes quality of life, describes different methods of assessing it, discusses its relevance in general and also specifically in patients with salivary gland diseases, and finally focuses on methods that can reduce the negative side effects of radiotherapy.

Definition and Concept

The World Health Organization (WHO) has defined quality of life as “an individual’s perception of their position in life in the context of the culture and value systems in which they live and in relation to their goals, expectations, standards and concerns.”1 This concept includes several different aspects or dimensions of life—i.e., physical health, psychological well-being, and social relationships (Fig. 41.1). The patient’s degree of independence and features of the environment can be considered as additional dimensions. Most assessment tools (see below) are therefore constructed to include multiple dimensions.

Another important conceptual issue is the point of view from which the assessment is made. In most approaches, it is implied that the patient is evaluating his or her own well-being, and quality of life is thus considered to be similar to self-perceived health. However, some authors, often implicitly, use the “quality of life” to refer to objective measurements—i.e., assessment by physicians, nurses, or proxies. For reasons of comparability, it is recommended that the term “quality of life” should only be used when self-assessment is meant, in accordance with the WHO definition.

Physicians who want to include quality of life in their treatment considerations have to decide what they are aiming for. From a holistic perspective, quality of life focuses on the patient’s subjective suffering and individual needs and wishes, depending on the context. In an analytical approach, on the other hand, a (virtual) standard is set and the degree of deviation from that standard is measured. In clinical trials, the latter approach is usually applied, whereas physicians in practice often use the first one. This chapter offers an overview of possible measurement tools for patients with salivary gland diseases, along with suggestions for when to use which type of assessment.

Fig. 41.1 The dimensions involved in quality of life.

Measurement

Measurement Tools

Measurement Tools

The two main methods of psychometric assessment in general are interviews on the one hand, and questionnaires on the other. As the broadest application of quality of life instruments is in clinical trials, self-administered questionnaires are most often used, because of their brevity and ease of analysis.

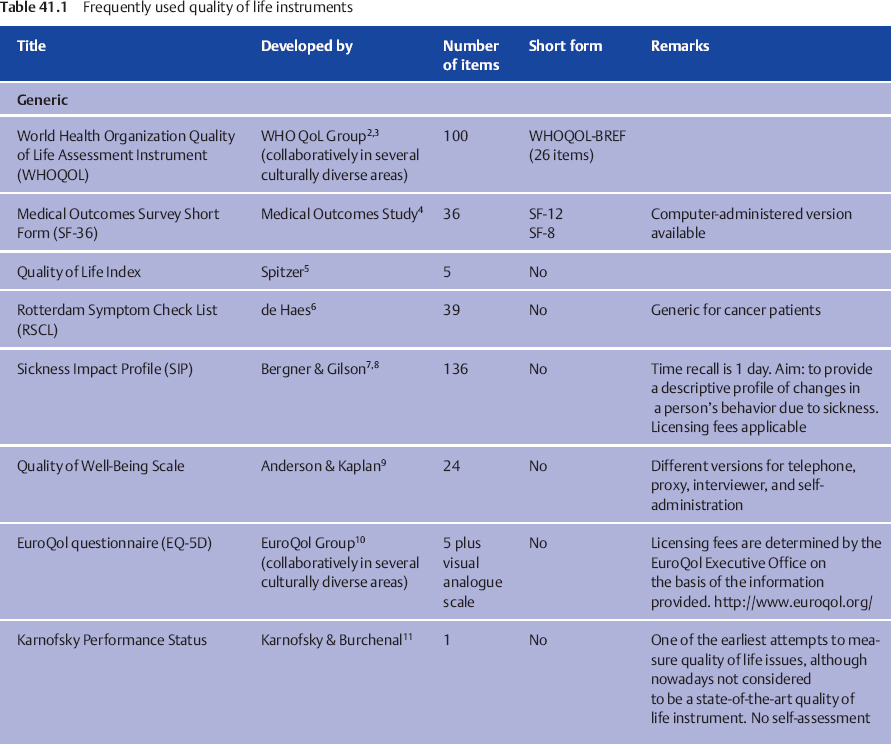

The questionnaires can be classified into generic and specific instruments. Generic instruments first measure general aspects of quality of life along the main dimensions outlined by the WHO (e.g., physical fitness, pain, and anxiety) and these are developed in greater detail for specific conditions or problems such as cancer, sexual functioning, or fatigue. Some instruments have a generic core questionnaire to which more specific modules can be added.

Quality of life questionnaires are usually developed in several phases. Firstly, the issues relevant to a specific health problem are collected and rated for their importance and relevance. Secondly, items are formulated from the issues and a provisional questionnaire is pilot-tested in a group of patients. Finally, after rephrasing and shortening, the final questionnaire is validated, preferably in different clinical and cultural settings. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in the United States gives permission for a drug only if the quality of life instrument used in the trial was developed with patient involvement from the initial phases onward.

Some frequently used questionnaires are listed in Table 41.1. More instruments, with detailed descriptions and reviews, are available from the Patient-Reported Outcomes and Quality of Life Instruments Database at www.proqolid.org.

The choice of the optimal instrument for a specific study or for use in clinical routine has to be considered. Inevitably, there is no instrument that is capable of covering all of the quality of life issues that are imaginable in salivary gland diseases while at the same time being short and cost-effective. All questionnaires should of course be reliable and valid. However, depending on the purpose of the study, the investigator needs to take further decisions by prioritizing what is most important: cross-cultural comparability, brevity, comprehensiveness, or comparability with healthy populations, for example. The remarks listed in the last column of Table 41.1 and the information about the number of items in the questionnaire can serve as a guide for finding a suitable instrument. For example, if a multinational field study is being planned in which a wide range of quality of life issues in patients with different types of head and neck cancer after radiotherapy are to be investigated, then the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire on the Head and Neck (EORTC QLQ–H&N) or the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy, Head and Neck Module (FACT–HN) would be good options. On the other hand, if a trial is being undertaken to study the effect of different types of physical exercise on fatigue and general discomfort in patients with Sjögren syndrome, the short form of the Profile of Fatigue and Discomfort Sicca Symptoms Inventory (PROFAD–SSI) would probably be the best choice. However, if the investigator would like to compare the fatigue level in patients with Sjögren syndrome with other patient groups, the Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory (MFI) would be preferable.

One of the earliest scales developed to measure quality of life is the Karnofsky performance scale, also known as the Karnofsky index.11 This instrument, first published in 1949, assesses the patient’s physical functioning and their abilities to care for themselves. Although this is one of the most frequently used scales, its reliability and sensitivity to change are poor,29 and it should therefore only be used in conjunction with more comprehensive and reliable tools. As a general rule, we would discourage investigators from using the Karnofsky scale as a quality of life measurement tool, due to its poor reliability and validity.

Challenges in Assessing Quality of Life

Challenges in Assessing Quality of Life

It may be common sense that the perceived quality of life is an important predictor of satisfaction and thus relevant to healthcare planning. However, quality of life is still not routinely measured in clinical practice. Measuring quality of life is compulsory in clinical trials, but the analysis of the data is often unsatisfactory. Why is this?

There are some possible explanations. Firstly, it may be that the investigators and physicians do not have sufficient information about how to analyze the questionnaires used. They may be discouraged by the multidimensionality of the instruments, which results in multiple outcomes—something that is usually considered negative in clinical trials. As a consequence, investigators sometimes calculate the total scores for different scales that are psychometrically and clinically unrelated, resulting in meaningless outcomes.

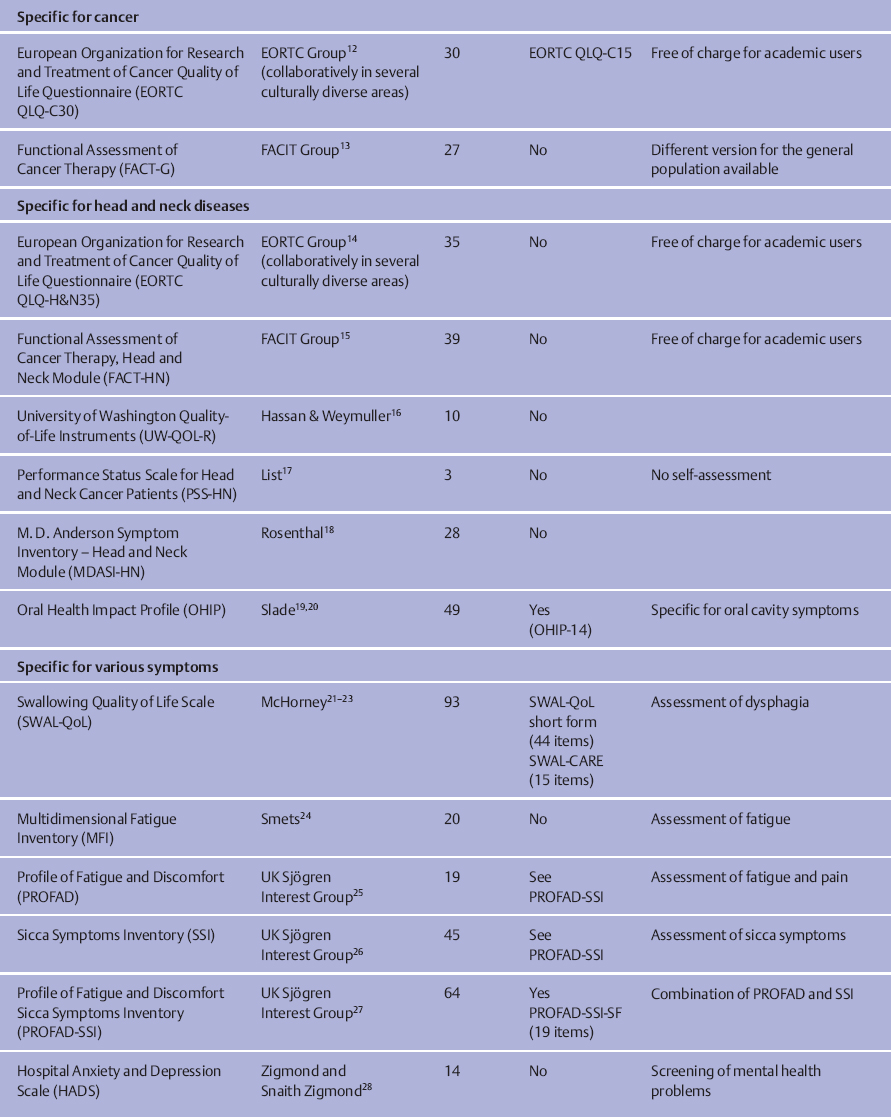

Fig. 41.2 The psychological nature of self-assessments.

Secondly, the physician may be puzzled by the psychological nature of self-assessments in general. Quality of life is a conglomerate of expectations, perceptions, and comparisons with other people (Fig. 41.2). Whether or not we are satisfied in a certain situation depends on our expectations, on the one hand, and the assessment of reality—i.e., the extent to which the expectations have been fulfilled—on the other. If someone does not expect to live without suffering, he will be able to put up with greater health problems than other people. In other words, if a patient says he is not experiencing any problems with a certain treatment, it might mean that there are genuinely no side effects, or it might mean that he does not regard a problem as being important enough to be mentioned to the doctor.

Another part of the psychological adjustment process involves comparison with other people. For example, if a patient who has undergone radiotherapy for a parotid tumor meets other patients who have received the same treatment and who are worse off than him, he may think himself lucky for having fewer side effects and will probably indicate a better health status in a questionnaire in comparison with a patient who only meets fellow patients who have fewer problems than he does. This phenomenon is known as top-down or bottom-up comparison.

Thirdly, it has been shown that patients tend to report only problems they consider relevant to their disease.30 For example, when a cancer patient is asked whether he has experienced pain during the past week, he may only think that tumor pain is relevant, but not the migraine he was suffering from the day before. This selective reporting can lead to an underestimation of patients’ health problems. It therefore makes more sense to compare subgroups of patients, rather than comparing patients with general population samples.

Another challenge is the difference between objective and subjective measurements—i.e., the fact that patient-reported outcomes do not correlate well with objective tests such as sialometry.31–33 For example, Suh and colleagues investigated 78 patients with xerostomia by comparing salivary flow rates and oral dryness as experienced by the patients.32 They found that the feeling of having a dry mouth did not correlate at all with actual salivary function.

Taking all of these psychological processes together makes it easier to understand the sometimes surprising results obtained from quality of life measurements—for example, the so-called “satisfaction paradox,” in which patients with severe diseases indicate a better quality of life than healthy individuals. These challenges sometimes lead to confusion and frustration in the investigating physician; however, this does not mean that quality of life measurements are invalid. Many of the challenges mentioned above can be detected, understood, and addressed.

It needs to be appreciated that quality of life always represents the patient’s subjective perspective. Taking both subjectively and objectively measured assessments together can therefore give us a more complete picture of reality. Neither approach alone should be used as a basis for treatment guidelines.

Specific Problems in Salivary Gland Diseases

Saliva is involved in the most essential human activities—eating (teeth, taste, swallowing), intimate social relationships, crying, speaking, etc. Diseases of the salivary glands are generally not life-threatening, but they are often painful and restrict activities of daily living. Each person produces approximately 1.5 L of saliva per day, and if saliva is overproduced or underproduced, the consequences can be devastating for the patient.

In diseases in which saliva is reduced (for example, in patients with Sjögren syndrome or after radiotherapy for head and neck neoplasms), patients often feel “dry,” both figuratively and literally. Comprehensive clinical care should address these concerns and offer adequate support, not only including drugs and adaptive devices, but also physical exercises and psychotherapy, for example.

When saliva production is increased, as in patients with Parkinson disease, the social component of quality of life becomes more relevant. In our society, drooling is considered to be appropriate only in infants, not in adults. Patients can therefore feel stigmatized and tend to withdraw socially. Health professionals should take note of this and help patients avoid a vicious circle of withdrawal and feelings of stigmatization.

Sjögren Syndrome

Sjögren Syndrome

Primary Sjögren syndrome is a chronic, systemic autoimmune disease characterized by inflammation of exocrine glands and functional impairment of the salivary and lachrymal glands.34 The main symptoms are dry eyes and dry mouth, but Sjögren syndrome can also cause skin, nose, and vaginal dryness. Apart from feeling dry, patients often complain about problems with smell and taste,35 depression,36,37 and fatigue—i.e., feelings of exhaustion and tiredness that do not improve after sleeping.34,38–41 Interestingly, fatigue correlates strongly with the global quality of life, whereas sicca symptoms do not.34 The reasons for increased levels of fatigue in patients with Sjögren syndrome are not yet well understood. Several mechanisms have been proposed, which are not mutually exclusive,40 in which interrelationships between biological and psychosocial factors need to be considered.

Psychosocial Determinants

One of the possible psychosocial determinants discussed is depression, as this occurs relatively frequently in conjunction with fatigue. However, patients may feel depressed as a consequence of chronic fatigue as well, making it difficult to disentangle the direction of causality. Another explanation is that fatigue and depression share common underlying mechanisms, such as neuroendocrine dysregulation. Segal and colleagues have shown that learned helplessness correlated with depression and with fatigue in patients with primary Sjögren syndrome.42 Learned helplessness is a psychological construct that is helpful in understanding the development of depressive mood and can be used in consultations with patients who request advice about how to manage fatigue.

Physiological Determinants

With regard to physiological determinants of fatigue, the research findings are generally inconsistent and sometimes conflicting. It appears that cytokines play a certain role—interleukin-6 levels, for example, are raised in serum, tears, and saliva.40 Neuroendocrine disturbances such as hypoadrenalism and increased serotonin production have been discussed as possible predictors of fatigue as well, although endocrine treatment options have so far been disappointing.

Malignant Salivary Gland Tumors

Malignant Salivary Gland Tumors

Cancer is regarded as the most dangerous disease by the majority of the general population—much more frequently than stroke, coronary heart disease, diabetes, or mental health problems,43 although all of these conditions are leading causes of death in high-income countries. Consequently, and of course because cancer is a potentially life-threatening disease, one of the leading quality of life problems in patients with head and neck cancer is fear.44,45 In a recent survey by the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Group in patients with head and neck cancer and among healthcare professionals, fear of recurrences was the most important quality of life issue, according to the patients (ranked in first and second place out of 92 possible issues). It was notable that the professionals rated this problem as being far less important—ranked in places 18 and 46.46 Fear is necessary to some extent, as it motivates patients to undergo uncomfortable or even painful but necessary diagnostic and treatment procedures. On the other hand, when fear becomes overwhelming, patients need psychosocial and at times psychotherapeutic support to enable them to deal with it.

Sticky saliva and dry mouth are common symptoms when patients have undergone radiotherapy. These problems often do not improve even years after the treatment,47–52 and patients should be prepared for this. Frequently, the long-term effects of hyposalivation also involve the teeth.53 The use of intensity-modulated radiotherapy is crucial in reducing these problems.54,55

Current treatments for head and neck cancer are increasingly including chemotherapy along with radiotherapy. The consequences for quality of life (swallowing difficulties, pain in the mouth, changes in taste perception) are often severe56,57 and should be taken into account in decision-making about treatment options.

In patients with malignant salivary gland tumors, surgery may be extensive—for example, with facial nerve paralysis or involvement of the mandible and skin, which can result in facial disfigurement.58 Fear of social stigmatization is common when the patient feels physically blemished. Physicians, nurses, psycho-oncologists, and members of support groups play an important role here in preventing withdrawal and social isolation of the patient.

Benign Salivary Gland Tumors

Benign Salivary Gland Tumors

Parotidectomy is the treatment of choice for benign tumors; however, patients’ perception of their quality of life after benign surgery has only been studied by a few authors.

Guntinas-Lichius et al. have reported59 that approximately half of patients who undergo surgical management for parotid pleomorphic adenoma report gustatory sweating, although treatment for this was required only in a minority of the patients. Only 5% of the patients in the study developed permanent partial paresis, and permanent total paresis was not seen—showing that careful surgical planning and standardization of parotidectomy can reduce the impact of surgery on quality of life.

In a subsequent study,60 the same group investigated quality of life prospectively in 34 patients undergoing benign surgery. The results showed that quality of life was not significantly decreased or increased overall 1 year after parotidectomy; only scores for sexuality were poorer. However, the patients indicated that on average they were experiencing more problems with opening the mouth and were using painkillers less frequently 1 year after the operation.

As in surgery for malignant disease, facial disfigurement can be an important problem after benign surgery as well.61 However, the most significant and persistent problem appears to be Frey syndrome.62

Other Conditions

Other Conditions

Other conditions that can cause impaired salivary gland functioning are human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immune deficiency syndrome,63,64 chronic graft-versus-host disease, more advanced age,65–67 and chronic hepatitis C infection, for example. Some medications (e.g., cloni-dine, diuretics, or hemodialysis) also cause oral dryness, with a severe impact on the patients’ quality of life.68 Intense pain can be caused by sialolithiasis, whereas sialorrhea can appear in Parkinson disease, after stroke, and in neurologically impaired children.69

Measures to Improve Quality of Life

Treatment for Xerostomia

Treatment for Xerostomia

Treatment for xerostomia is still challenging.70–74 Salivary substitutes may provide some temporary relief, but using ordinary water appears to be equally good.70 Salivary stimulants (pilocarpine) have been shown to have limited success in prevention, but may be helpful for treating dry mouth. Tissue transfer strategies have been investigated experimentally, but are not yet available for clinical purposes.75 Acupuncture and acupuncture-like transcutaneous nerve stimulation are other promising options,76 but larger phase III trials are still lacking. Self-hypnosis was used in a carefully conducted pilot study,33 and the results showed that even patients with severe xerostomia were able to obtain relief with this method. Further studies are definitely needed in this field.

The main method of minimizing the impact of xerostomia is to prevent damage to the salivary glands by using sparing techniques in radiotherapy and surgery (see Chapter 42).

Treatment for Sialorrhea

Treatment for Sialorrhea

Sialorrhea (drooling) can be treated with radiotherapy,77 injection of botulinum toxin,78 or most effectively with submandibular duct repositioning.69,79,80

Treatment for Fatigue

Treatment for Fatigue

Fatigue is the prevalent symptom in patients who report that they are always tired and exhausted. The first step in treating fatigue is a careful diagnostic evaluation, including identification of the main type of fatigue involved. If the main problem is mental fatigue, the patient primarily needs psychological counseling and training.40 However, if the key symptom is physical fatigue, then exercise81 is the most promising form of treatment. A multidisciplinary team should be involved in patient care in all such cases.

Treatment for Depression

Treatment for Depression

As with mental fatigue, depression requires consultation in most cases. Antidepressant medication is useful at times, but should not be given without considering other treatment options. Psychotherapy has been shown to be effective in treating depression,82,83 but not all patients with increased levels of anxiety or depression need professional psychotherapeutic treatment. In most cases, patients expect psychosocial support from their doctor and/or nurse.84 According to the results of an international consensus conference,85,86 experts in mental health care should become involved in the treatment if one of the following conditions is met:

The patient has severe levels of distress

The patient has severe levels of distress

The patient expresses a desire to receive psychotherapy

The patient expresses a desire to receive psychotherapy

The patient has very little social support at home

The patient has very little social support at home

Mr. Smith, the patient described at the beginning of this chapter, was suffering from severe quality of life problems, fatigue, and depression. He definitely benefited from receiving professional psycho-oncological support at the end of his life. Although we were not able to relieve his saliva problems, he was able to regain a sense of personal dignity by expressing his fears, despair, and sadness.

Quality of life is a multidimensional construct.

Quality of life is a multidimensional construct.

Measurements of quality of life should always include the patient’s viewpoint.

Measurements of quality of life should always include the patient’s viewpoint.

Understanding psychological processes of adjustment and coping can help solve problems in assessing quality of life.

Understanding psychological processes of adjustment and coping can help solve problems in assessing quality of life.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses