Introduction

Orthodontic forces produce a series of changes in dental pulp. However, no one has attempted to investigate the incidence of pulp necrosis after orthodontic therapy in the clinic. In this study, we aimed to investigate pulp vitality and histologic changes after the application of moderate and severe intrusive forces.

Methods

Twenty-seven adolescent patients were assigned to 1 of 3 groups: the control group of 3 subjects; the moderate-force group, with 12 subjects who received a 50-g force to the first premolars bilaterally; and the severe-force group, with 12 subjects who received a 300-g force. The forces were applied for 1, 4, 8, or 12 weeks. An electric pulp tester was used to test for vitality, and teeth that did not respond to the electric pulp tester were subsequently tested thermally with a stick of heated gutta-percha.

Results

The teeth with a negative response to the electric pulp tester still responded to the thermal test. We found odontoblast disruption, vacuolization, and moderate vascular congestion in both force groups, but no necrosis was observed. Pulp stones were formed only in the severe-force group.

Conclusions

Dental pulp still has vitality after intrusive treatment with different forces. These data provide new insights into the effects of intrusive orthodontic forces.

Orthodontic forces are known to produce a series of changes in dental pulp after tooth movement. As a consequence of environmental constraints in a rigid and noncompliant shell, changes in pulpal blood flow or vascular tissue pressure have serious implications for the health of dental pulp. The main pulp changes after the application of intrusive forces include vacuolization of the pulp tissue, circulatory disturbances, congestion, hemorrhage, and fibrohyalinosis.

It has been suggested that injury from orthodontic forces might be permanent, and the pulp could eventually lose its vitality. However, other studies showed that orthodontic forces had no significant long-lasting effects. A recent study showed that heavier forces applied during rapid palatal expansion were more likely to affect the pulpal vasculature, but the pulp of the posterior permanent teeth was still vital. Darendeliler et al found that 50 g of constant and continuous force could produce the ideal amount of tooth movement, but exceeding this force might cause periodontal ischemia, leading to root resorption. However, no study has attempted to investigate the incidence of pulp necrosis after orthodontic therapy in the clinic. Therefore, in this study, we aimed to investigate the histologic alterations of the dental pulp resulting from the application of moderate and severe orthodontic forces and to determine whether dental pulp loses its vitality after the application of a severe orthodontic force.

Material and methods

This study was conducted on 54 maxillary first premolars collected from 27 prospective orthodontic patients (15 male, 12 female) with a mean age of 17.9 years (range, 14-24 years) who required first premolar extractions. The 27 subjects were randomly divided into 3 groups: the control group without orthodontic forces (3 subjects), the moderate-force group (12 subjects), and the severe-force group (12 subjects). The moderate-force group had 50 g of buccally directed orthodontic intrusive force on both sides, and the severe-force group had 300 g of force. The experimental first premolars were extracted 1, 4, 8, or 12 weeks after the initial force application (6 teeth from each group were extracted at each time).

All study participants met the following criteria: (1) no major systemic disease, (2) no medication use, (3) healthy periodontium (minimal gingival inflammation, probing depths ≤3 mm, and no bone loss as determined by radiographs), (4) no endodontically treated teeth, (5) no trauma history, (6) complete root development determined radiographically (and confirmed visually after extractions), and (7) no moderate or severe crowding. The study was approved by the institutional review board of Jilin University in Changchun, China, and all participants gave informed consent.

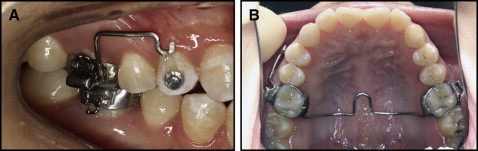

A lingual button was bonded onto the buccal surfaces of the maxillary first premolars. Intrusive orthodontic forces were applied by a clear closed elastomeric chain (ORMAER; Dentsply Raintree Essix Glenroe, Sarasota, Fla) ( Fig 1 , A ). The force magnitude was measured with a strain gauge (Dentaurum, Ispringen, Germany) at the beginning of the intrusion to ensure that proper forces were applied. The elastomeric chain was changed each time the patients revisited, once a week. A transpalatal arch was used to reinforce the anchorage ( Fig 1 , B ). For the moderate-force (50 g) group, a transpalatal arch was used to reinforce the anchorage 4 weeks before the application of the force, and a Nance arch was additionally used to reinforce the anchorage 8 weeks after the application of the force. For the severe-force (300 g) group, both transpalatal and Nance arches were used to reinforce the anchorage immediately after the application of the force.

An electric pulp tester (Analytic Technology, Redmond, Wash) was used in this study. Toothpaste was the conducting medium. The testing site was confined to the buccal cusp tips of the molars and the premolars. Teeth that did not respond to the electric pulp tester were tested thermally with a stick of heated gutta-percha (hot testing). All teeth were isolated with cotton rolls and dried thoroughly before testing. The testing procedure was explained to the patients. The readings of the electric pulp tester were recorded, and the results of the thermal testing were recorded as a positive or a negative (yes or no) response.

Electric pulp tests were performed immediately before placement of the lingual button to provide a baseline for the study and at 1, 4, 8, and 12 weeks after the intrusion treatment.

At week 1, 4, 8, or 12 after the treatment, teeth were extracted by an oral surgeon with minimum trauma. After extraction, the crown of each tooth was cut with a bur to facilitate the fixation, and the tooth was fixed in 10% formalin for 1 week. Then the specimens were decalcified and embedded in paraffin. Serial sections (5 μm thick) were cut longitudinally from each tooth and stained with hematoxylin and eosin dye. The sections were evaluated using a computer image analyzing system (HPIAS-1000, version 6.0; Media Cybernetics, Silver Spring, Md).

Statistical analysis

The data were processed with SPSS software (version 11.5; SPSS, Chicago, Ill). The electric pulp tester data were analyzed using the Student t test and 1-way analysis of variance. P <0.05 indicated a statistical difference.

Results

The total measurement period was from 1 week to 12 weeks after the application of the orthodontic force. Teeth that did not respond to the electric pulp tester underwent subsequent thermal testing. All teeth still responded positively to the thermal test. As shown in the Table , the teeth in the severe-force group responded negatively to the electric pulp tester from 4 to 12 weeks, whereas the teeth in the moderate-force group had no response from 8 to 12 weeks. When the teeth responded to the electric pulp tester, there were significant differences between the moderate-force and severe-force groups at weeks 1, 2, and 3 ( P <0.05). Readings of the moderate-force group at weeks 2 and 4 were significantly increased compared with those at baseline ( P <0.05). In addition, there were significant differences between the readings of the moderate-force group at weeks 5, 6, and 7 and those at baseline ( P <0.001). After 4 weeks, pulp vitality measurements became significantly different from those during the previous weeks ( P = 0.009). Readings of the electric pulp tester increased over time in the severe-force group, but showed no statistical difference ( t = 3.799; P = 0.06).

| Week | Moderate-force group | Severe-force group | t | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Teeth (n) | EPT reading | Teeth (n) | EPT reading | |||

| 0 | 24 | 3.44 ± 2.37 | 24 | 5.33 ± 2.45 | 1.900 | 0.07 |

| 1 | 6 | 4.50 ± 2.56 | 6 | 6.63 ± 1.77 | 2.10 | 0.047 ∗ |

| 2 | 6 | 5.20 ± 2.57 † | 6 | 7.20 ± 0.84 | 2.23 | 0.045 ∗ |

| 3 | 6 | 4.29 ± 2.36 | 6 | 7.67 ± 0.58 | 3.55 | 0.009 ∗ |

| 4 | 6 | 6.43 ± 2.07 † | 6 | 0 | ||

| 5 | 6 | 7.68 ± 0.35 ‡ | 6 | 0 | ||

| 6 | 6 | 8.35 ± 0.38 ‡ | 6 | 0 | ||

| 7 | 6 | 8.67 ± 0.43 ‡ | 6 | 0 | ||

| 8 | 6 | 0 | 6 | 0 | ||

| 9 | 6 | 0 | 6 | 0 | ||

| 10 | 6 | 0 | 6 | 0 | ||

| 11 | 6 | 0 | 6 | 0 | ||

| 12 | 6 | 0 | 6 | 0 | ||

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses