Orthognathic surgery has four basic treatment phases: (1) presurgical orthodontics to align and level the teeth over basal bone; (2) orthognathic surgery to position the dento-osseous structures of the maxillo-mandibular complex into the proper functional and esthetic positions with appropriate stabilization; (3) postsurgical patient management and orthodontics to finalize the occlusion and treatment outcome; and (4) long-term orthodontic retention. Postsurgical patient management is a critical factor for high-quality patient treatment and predictable outcomes in orthognathic surgery. However, lack of understanding of proper patient management on the part of the surgeon and orthodontist can result in compromised or even disastrous results. Poor postsurgical patient management after an initially great surgical result can produce a compromised or unacceptable outcome. Although often difficult, a compromised surgical result may be salvaged by aggressive postsurgical orthodontics and patient management. Surgeons and orthodontists must have the knowledge and ability to implement postsurgical management protocols and strategies to provide the best care and outcomes possible for their orthognathic surgery patients.

Jaw deformities requiring orthognathic surgery often coexist with temporomandibular (TMJ) pathology. Unrecognized or untreated TMJ pathology is one of the primary factors leading to postsurgical complications, resulting in poor quality and unpredictable outcomes. TMJ surgery may be required in these coexisting situations to obtain the highest quality results for patients. However, the TMJ surgery should be done before the orthognathic surgery in separate operations, or the TMJ surgery should be followed by the orthognathic surgery at the same operation. TMJ problems must be identified and properly managed in the orthognathic surgery patient.

This chapter presents basic concepts, philosophies, treatment protocols, and other important information that can be helpful in postsurgical patient management. The information is primarily directed toward patients requiring double-jaw surgery, with additional factors in reference to TMJ surgery. Patients undergoing single-jaw surgery usually progress somewhat easier than patients having double-jaw surgery and/or TMJ surgery. In addition, this chapter discusses the most common postsurgical complications and the appropriate management. Variations to this information may exist based on individual orthodontists’ and surgeons’ training, knowledge, and experience, but the basic premises are appropriate. Also, individual patient variability exists regarding the psychological and physiologic effects of surgery, healing abilities, genetic factors, health and preexisting conditions, nutrition, habits, and so forth that are important to the healing process.

SURGICAL FACTORS TO ENHANCE POSTSURGICAL ORTHODONTICS

The surgeon can simplify postsurgical patient management and orthodontic requirements by the following methods: (1) perform precise surgery; (2) segmentalize the maxilla when indicated to improve outcome stability; (3) use surgical stabilizing splints when indicated; (4) use rigid fixation achieving appropriate stability in the mandible and maxilla; (5) graft maxillary bone defects with bone or synthetic bone to improve stability and facilitate healing ; (6) maximize occlusal interdigitation at surgery; and (7) surgically correct TMJ pathology either at a separate surgical procedure before the orthognathic surgery or at the same operation as the orthognathic surgery. Besides poor surgical technique and inadequate rigid fixation, failure to identify and properly treat TMJ pathology is one of the most common factors that leads to relapse and failure of orthognathic surgical procedures.

At the completion of surgery, a surgical stabilizing splint may be present and wired to the upper teeth. Light elastics (3½ oz) usually are placed between the upper and lower arches in the cuspid and molar areas, and/or elsewhere if indicated, to (1) maximize the occlusal fit, (2) take stress off the muscles of mastication by providing extra vertical support to the jaws to improve patient comfort, and (3) reduce swelling in the TMJ if TMJ surgery was simultaneously performed. After surgery, some patients feel the necessity to clench and keep their teeth in tight contact. This can cause muscle tension, discomfort, pain in the muscles, and undue stress to the osteotomy sites. Patients should be informed that for unaffected individuals (those not undergoing surgery), when the jaws are relaxed the teeth usually are separated with a free space and are not forced together.

After surgery, the use of light vertical directional elastics helps support the jaws and decreases tension in the masticatory muscles, although some patients feel better without elastics in place. If the occlusion is good, then elastics may not be necessary if appropriate rigid fixation is used at surgery. When TMJ surgery is simultaneously done with the orthognathic surgery, the use of light class III directional elastics for a few days after surgery will minimize TMJ edema. If postsurgical TMJ edema develops, then the occlusion can shift toward a class III end-on relation. Class III elastics will then be necessary to reapproximate the occlusion into a class I relation. Minimizing the TMJ edema immediately after surgery with elastics typically is easier than recapturing the occlusion later.

SPLINTS

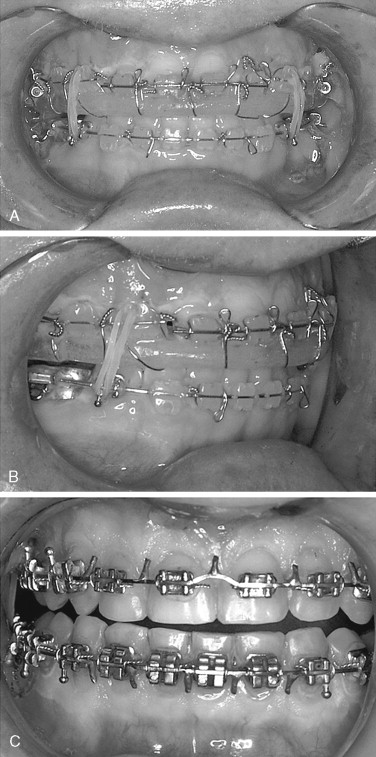

Surgical stabilizing splints are indicated to provide (1) stability in multiple segmental surgery of the maxilla or mandible, (2) transverse stability when the maxilla and/or mandible have been expanded or narrowed, (3) occlusal support when key teeth are missing (e.g., when first, second, and third molars are missing in a quadrant), and (4) a means to interdigitate the occlusion if teeth are severely worn or missing. Two basic types of maxillary splints are used for orthognathic surgery; the palatal splint ( Figure 19-1 ) and the occlusal coverage splint ( Figure 19-2 ). If the maxilla and mandible are single pieces and the teeth can be appropriately interdigitated, then a final splint usually is not necessary in single- or double-jaw surgery.

PALATAL SPLINT

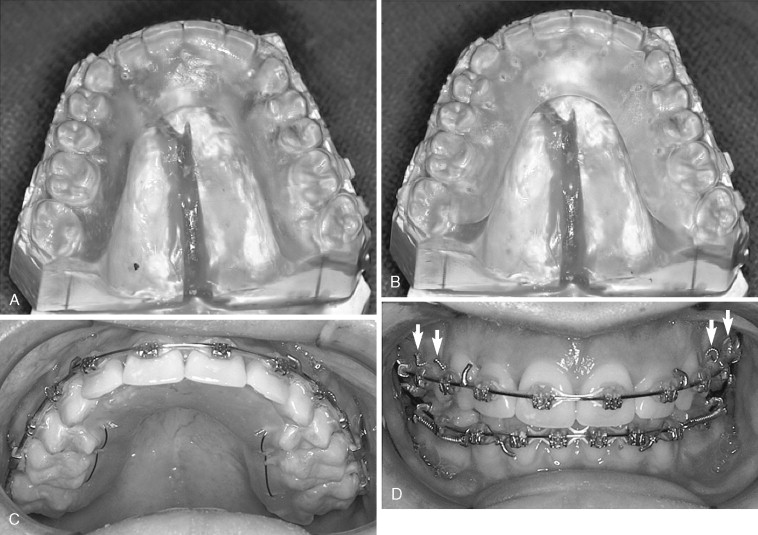

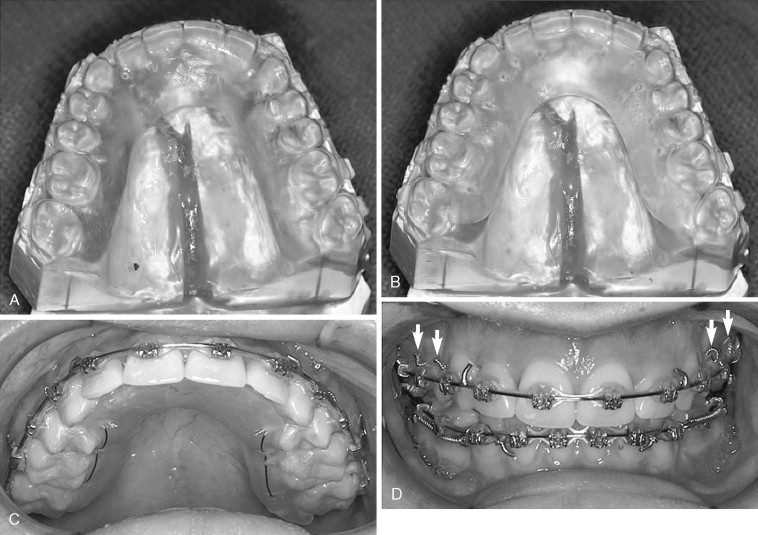

This horseshoe-shaped splint (see Figure 19-1 ) is preferred by the author because (1) it provides excellent stability; (2) the occlusal interrelations can be maximized and observed (the teeth and occlusal relations are not covered and hidden by the splint); (3) it is easier to keep the teeth and splint clean; (4) orthodontic treatment can be performed with the splint in place, including arch wire changes; (5) it can be left in place for extended period (2 to 3 months or longer if necessary); and (6) after removal, the splint can be modified to function as a retention splint by adding clasps. When making the splint, the palatal tissues beneath the splint must have wax relief of approximately 1 to 2 mm on the dental model so the splint does not impinge on the soft tissues (see Figure 19-1, A and B ). If the splint is constructed to sit against the soft tissues, a major risk of vascular compromise to the maxilla could occur, resulting in a potentially disastrous outcome. The splint is stabilized to the maxilla with light, 28-gauge stainless steel wire placed through the splint and circumferentially around the first molars and first bicuspids (second bicuspids if the first bicuspids are missing), and wires are twisted on the labial side of the teeth (see Figure 19-1, C and D ). The anterior teeth are not tied into the splint because the anterior segment could become displaced because of the cingulum morphology that will displace the segment superiorly and posteriorly. At surgery the anterior segment is stabilized with bone plates.

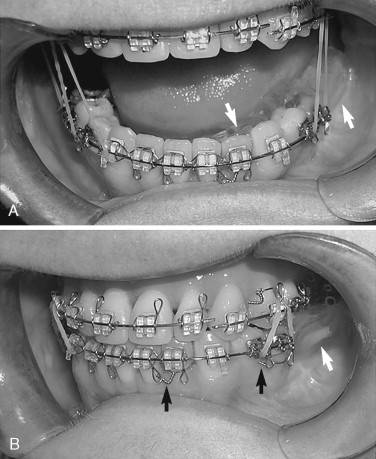

OCCLUSAL COVERAGE SPLINT

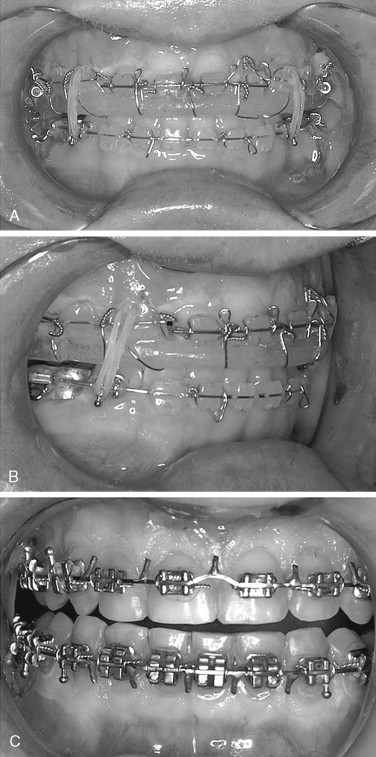

The occlusal coverage splint is the most common type of maxillary splint used and has the following advantages: (1) it is easy to construct, (2) it provides transverse stability, and (3) it can “lock in” the occlusion perhaps better than the palatal splint (see Figure 19-2, A and B ). However, the occlusal coverage splint presents the following possible complicating factors: (1) the clinician cannot see the occlusal interrelation of the teeth with the splint in place, (2) an occlusal interference caused by the splint could result in a malocclusion, (3) postsurgical orthodontics could be much more difficult, (4) the arch wire cannot be changed with the splint in place, (5) orthodontics cannot be performed with the splint in place, (6) oral hygiene is more difficult to maintain, and (7) discoloration, decalcification, and caries of the teeth can occur where covered by the splint. The splint usually is stabilized to the maxillary arch with wires placed through the buccal flange of the splint and around the adjacent orthodontic brackets on the teeth.

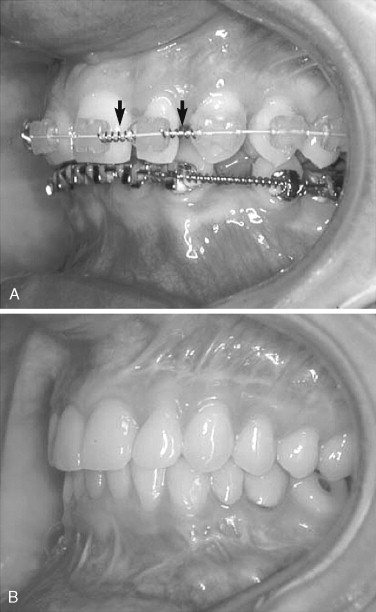

MANDIBULAR SPLINT

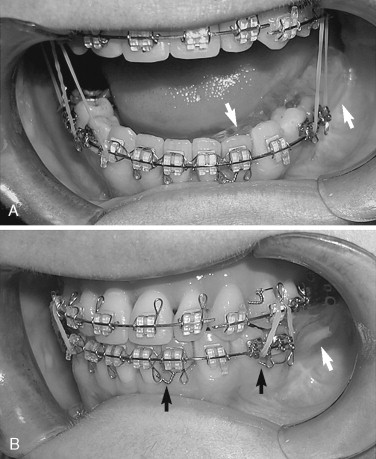

Mandibular splints may be indicated for the following reasons: (1) to assist in stabilizing the mandible and segments after body osteotomies, subapical osteotomies, symphysis and sagittal split osteotomies; (2) to provide transverse stability if the mandible is expanded or narrowed by osteotomies or distraction osteogenesis; and (3) to replace missing teeth ( Figure 19-3 ). Splints for providing transverse stability can be constructed to fit around the lingual aspect of the mandibular crowns, similar to the maxillary palatal splint. Therefore these splints can be maintained in position for an extended period (2 to 3 months or longer) if required. The splints can be secured to the mandibular arch by placing retention wires through the splint and circumferentially around the first molars and first bicuspids (second bicuspids if the first bicuspids are absent) (see Figure 19-3 ). With this splint design, orthodontic arch wire changes and mechanics can progress with the splint remaining in place. Clasps can be placed on the splint after removal of the surgical retention wires so that the splint can be used as a removable retainer.

Although splints are commonly necessary for stabilization and jaw positioning, some negative factors are involved: (1) considerable time may be required before surgery to mount models, perform the model surgery, and construct the splints; (2) oral hygiene is compromised; (3) speech is adversely affected while the splint is in place; (4) the device can be irritating to the tongue, cheeks, and gingiva; (5) the splint can cause discoloration, decalcification, and caries; and (6) the splint can cause halitosis. Thus good oral hygiene is important after surgery.

SPLINT CARE

Because splints usually are wired in place and are food and debris traps, oral hygiene must be carefully maintained. Beginning the day after surgery, patients should be encouraged to brush their teeth and splint a minimum of 3 to 4 times per day with toothpaste as well as rinse the mouth several times per day with plain water or salt water. Chlorhexidine gluconate can be used two to three times per day to decrease plaque buildup. However, the teeth may become stained beneath the occlusal coverage splints. A Water-Pik (Philips, Amsterdam, The Netherlands) can be used at approximately 7 to 10 days after surgery on a low setting. Earlier use could damage the incisions. Over time, higher settings can be used.

SPLINT REMOVAL

This process requires cutting and removing the retention wires and then removing the splint. For most cases, the palatal or occlusal coverage splints can be removed 1 month after surgery. An exception is with large maxillary expansions (greater than 5 mm), in which the palatal splint can remain in position for 2 to 3 months or longer if required. After removal of the splint, a transpalatal arch bar, removable palatal splint, or heavy labial arch wire followed by postorthodontic retainers can be used to maintain the maxillary expansions for an extended period. The palatal splint can be modified to function as a removable splint by adding retention clasps. After removal, the palatal splint may be helpful in determining transverse stability. As long as the splint can be inserted into position without difficulty, the transverse dimension of the maxilla is stable. If the splint is difficult or can no longer be inserted, then transverse relapse has likely occurred. Maxillary or mandibular arches that have been expanded orthodontically or orthopedically, surgically assisted, or by osteotomies require long-term (1 to 2 years or longer) transverse stabilization after treatment to ensure a predictable outcome.

SPLINTS

Surgical stabilizing splints are indicated to provide (1) stability in multiple segmental surgery of the maxilla or mandible, (2) transverse stability when the maxilla and/or mandible have been expanded or narrowed, (3) occlusal support when key teeth are missing (e.g., when first, second, and third molars are missing in a quadrant), and (4) a means to interdigitate the occlusion if teeth are severely worn or missing. Two basic types of maxillary splints are used for orthognathic surgery; the palatal splint ( Figure 19-1 ) and the occlusal coverage splint ( Figure 19-2 ). If the maxilla and mandible are single pieces and the teeth can be appropriately interdigitated, then a final splint usually is not necessary in single- or double-jaw surgery.

PALATAL SPLINT

This horseshoe-shaped splint (see Figure 19-1 ) is preferred by the author because (1) it provides excellent stability; (2) the occlusal interrelations can be maximized and observed (the teeth and occlusal relations are not covered and hidden by the splint); (3) it is easier to keep the teeth and splint clean; (4) orthodontic treatment can be performed with the splint in place, including arch wire changes; (5) it can be left in place for extended period (2 to 3 months or longer if necessary); and (6) after removal, the splint can be modified to function as a retention splint by adding clasps. When making the splint, the palatal tissues beneath the splint must have wax relief of approximately 1 to 2 mm on the dental model so the splint does not impinge on the soft tissues (see Figure 19-1, A and B ). If the splint is constructed to sit against the soft tissues, a major risk of vascular compromise to the maxilla could occur, resulting in a potentially disastrous outcome. The splint is stabilized to the maxilla with light, 28-gauge stainless steel wire placed through the splint and circumferentially around the first molars and first bicuspids (second bicuspids if the first bicuspids are missing), and wires are twisted on the labial side of the teeth (see Figure 19-1, C and D ). The anterior teeth are not tied into the splint because the anterior segment could become displaced because of the cingulum morphology that will displace the segment superiorly and posteriorly. At surgery the anterior segment is stabilized with bone plates.

OCCLUSAL COVERAGE SPLINT

The occlusal coverage splint is the most common type of maxillary splint used and has the following advantages: (1) it is easy to construct, (2) it provides transverse stability, and (3) it can “lock in” the occlusion perhaps better than the palatal splint (see Figure 19-2, A and B ). However, the occlusal coverage splint presents the following possible complicating factors: (1) the clinician cannot see the occlusal interrelation of the teeth with the splint in place, (2) an occlusal interference caused by the splint could result in a malocclusion, (3) postsurgical orthodontics could be much more difficult, (4) the arch wire cannot be changed with the splint in place, (5) orthodontics cannot be performed with the splint in place, (6) oral hygiene is more difficult to maintain, and (7) discoloration, decalcification, and caries of the teeth can occur where covered by the splint. The splint usually is stabilized to the maxillary arch with wires placed through the buccal flange of the splint and around the adjacent orthodontic brackets on the teeth.

MANDIBULAR SPLINT

Mandibular splints may be indicated for the following reasons: (1) to assist in stabilizing the mandible and segments after body osteotomies, subapical osteotomies, symphysis and sagittal split osteotomies; (2) to provide transverse stability if the mandible is expanded or narrowed by osteotomies or distraction osteogenesis; and (3) to replace missing teeth ( Figure 19-3 ). Splints for providing transverse stability can be constructed to fit around the lingual aspect of the mandibular crowns, similar to the maxillary palatal splint. Therefore these splints can be maintained in position for an extended period (2 to 3 months or longer) if required. The splints can be secured to the mandibular arch by placing retention wires through the splint and circumferentially around the first molars and first bicuspids (second bicuspids if the first bicuspids are absent) (see Figure 19-3 ). With this splint design, orthodontic arch wire changes and mechanics can progress with the splint remaining in place. Clasps can be placed on the splint after removal of the surgical retention wires so that the splint can be used as a removable retainer.

Although splints are commonly necessary for stabilization and jaw positioning, some negative factors are involved: (1) considerable time may be required before surgery to mount models, perform the model surgery, and construct the splints; (2) oral hygiene is compromised; (3) speech is adversely affected while the splint is in place; (4) the device can be irritating to the tongue, cheeks, and gingiva; (5) the splint can cause discoloration, decalcification, and caries; and (6) the splint can cause halitosis. Thus good oral hygiene is important after surgery.

SPLINT CARE

Because splints usually are wired in place and are food and debris traps, oral hygiene must be carefully maintained. Beginning the day after surgery, patients should be encouraged to brush their teeth and splint a minimum of 3 to 4 times per day with toothpaste as well as rinse the mouth several times per day with plain water or salt water. Chlorhexidine gluconate can be used two to three times per day to decrease plaque buildup. However, the teeth may become stained beneath the occlusal coverage splints. A Water-Pik (Philips, Amsterdam, The Netherlands) can be used at approximately 7 to 10 days after surgery on a low setting. Earlier use could damage the incisions. Over time, higher settings can be used.

SPLINT REMOVAL

This process requires cutting and removing the retention wires and then removing the splint. For most cases, the palatal or occlusal coverage splints can be removed 1 month after surgery. An exception is with large maxillary expansions (greater than 5 mm), in which the palatal splint can remain in position for 2 to 3 months or longer if required. After removal of the splint, a transpalatal arch bar, removable palatal splint, or heavy labial arch wire followed by postorthodontic retainers can be used to maintain the maxillary expansions for an extended period. The palatal splint can be modified to function as a removable splint by adding retention clasps. After removal, the palatal splint may be helpful in determining transverse stability. As long as the splint can be inserted into position without difficulty, the transverse dimension of the maxilla is stable. If the splint is difficult or can no longer be inserted, then transverse relapse has likely occurred. Maxillary or mandibular arches that have been expanded orthodontically or orthopedically, surgically assisted, or by osteotomies require long-term (1 to 2 years or longer) transverse stabilization after treatment to ensure a predictable outcome.

POSTSURGICAL ORTHODONTICS

POSTSURGICAL APPOINTMENTS

The surgeon and/or orthodontist should see the patient on a weekly basis, or more often if indicated, for the first 1 to 2 months after surgery to check the occlusion and patient progress as well as make any indicated changes in the elastic or orthodontic mechanics to maximize the occlusal interrelation. If the occlusion fits properly, then elastics may not be necessary. Then, as long as the occlusion remains stable, the time span between appointments can be increased. The surgeon and orthodontist must coordinate this postoperative patient management.

PATIENT POSITION AT ASSESSMENT

Patient position is important when evaluating postorthognathic surgery occlusal relations. Patients should be in an upright or slightly reclined position, not in the reclined position used for routine orthodontic treatment. The mandibular condyles may set more inferior and posterior than usual, particularly shortly after surgery. Intercapsular edema also may cause the mandible to be postured slightly forward. If preexisting TMJ pathology that was not corrected is present, patients may “splint” by holding the mandible forward to decrease pressure on the TMJ, altering the centric relation occlusion. Of particular concern is when TMJ surgery has been performed at the same operation as the orthognathic surgery. The capsular ligaments have been cut, and in a reclined position the condyles can slide posterior and inferior to the centric relation position, yielding a false class II end-on occlusal relation. Setting the patient in an upright or only slightly reclined position and pushing gently upward at the angles of the mandible should seat the condyles into a centric relation to evaluate the occlusal interrelation more accurately.

AGGRESSIVE POSTSURGICAL ORTHODONTICS

If the occlusion is not “perfect” initially after surgery, then the surgeon and/or orthodontist must aggressively apply the appropriate elastic mechanics. Relatively light-strength elastics (3½ oz) usually is adequate to correct the situation. However, heavier elastics occasionally may be necessary. This can be accomplished by doubling up the 3½ oz elastics or using a stronger elastic. Delays in addressing postsurgical occlusal imbalances will result in much greater difficulties correcting the problem at a later time. If the occlusion was good at the completion of surgery but a shift has occurred or open bite has developed, the cause often is minor posterior occlusal changes that have caused interference. If light elastics do not reapproximate the occlusion, then placing heavy elastics in the appropriate direction for 30 minutes to an hour may settle the occlusion into position so that light elastics can then be used again. Although heavy-strength elastics occasionally are necessary, they usually are not required when the surgery has been properly and accurately performed. Occasionally equilibration of the teeth may be necessary to settle the occlusion into position. If a major postsurgical malocclusion is present, then assessment of postsurgical lateral cephalogram and TMJ tomograms may help determine if it is a correctable problem orthodontically or if additional surgical intervention is required. If required, usually the sooner the surgical intervention is performed, the better the situation for the patient and surgeon.

ELASTICS

Postsurgical interarch elastics are indicated to (1) maximize the occlusal fit, (2) provide orthodontic forces to correct postsurgical occlusal discrepancies, (3) take stress off the muscles of mastication to improve patient comfort immediately after surgery, (4) finalize the occlusion, and (5) minimize edema in the bilaminar tissues if simultaneous TMJ surgery was performed. Controlling the occlusion after surgery generally can be accomplished by using elastics with one or more of the following vectors, depending of the situation: class II, class III, vertical, box, triangle, trapezoidal, rhomboidal, cross arch, or anterior tangential for example. Usually only light-force elastics of 3½ oz with sizes of ⅛, 3 / 16 , ¼, and 5 / 16 inches are needed because teeth and bone segments (maxilla particularly) can move faster after surgery. If the occlusion fits together quite well, then elastics may not be necessary unless the patient requires elastics for improved comfort by providing vertical support for relieving tension on the muscles of mastication. As soon as possible after surgery, patients should be instructed on the placement and removal of their elastics to facilitate their dietary intake, oral hygiene, and jaw exercises.

Vertical Elastics

The use of anterior vertical elastics must be closely monitored. Although often necessary initially after surgery to provide vertical support to the jaws to decrease masticatory muscle tension and maximize the occlusal fit, these elastics also can create unwanted dentoalveolar changes. Patients who may be predisposed to these unwanted changes include (1) patients with nasal airway obstruction that was not corrected at surgery and who continue to be mouth breathers; (2) patients who habitually hold their jaws apart or in their work or play activities talk a lot, requiring the jaws to be held open; and (3) patients with short roots. Holding the jaws apart for extended periods with anterior vertical elastics will extrude the anterior teeth and over time increase the alveolar bone height. A degree of distraction osteogenesis also may occur in the maxilla. These changes may result in the development of posterior open bites, premature contact of the incisors, increased upper tooth/lip relation, and increased mandibular and maxillary anterior vertical height. Avoiding these factors may include one or more of the following actions: (1) perform stable presurgical orthodontics and accurate surgery to decrease requirements for vertical elastics; (2) discontinue vertical elastics as soon as possible; (3) decrease daily time requirements for wearing elastics, particularly during activities in which the jaws function in an open position; (4) use very light vertical therapeutic clenching to minimize vertical forces; (5) correct nasal airway obstruction and sleep apnea issues by performing the appropriate surgical procedures so the patients can breathe through the nose instead of the mouth.

Power Chains

Avoid the use of power chains in the upper arch after surgery. The use of power chains is a relatively common technique in the orthodontic finishing phase of treatment. However, power chain forces can create increased torque on the incisors, tipping the incisor edges posteriorly and tipping the root tips anteriorly. This can cause premature contact of the incisors with subsequent end-on incisor relation and development of posterior open bites. This can be a major problem, particularly in patients with tooth size discrepancies in whom spacing was created in the anterior arch to compensate for the tooth size differences. When this problem develops, the power chain should be removed and mechanics reversed to tip the incisor edges forward and the root tips posteriorly. This may involve reopening space between the lateral incisors and cuspids. This spacing can be eliminated afterwards orthodontically or with bonding, veneers, or crowns on the lateral incisors.

CHANGE ARCH WIRES

Segmental osteotomies in the maxilla or mandible commonly require the arch wire to be cut into sections. Crimping the wire ends, placing a bead of acrylic over the ends, or using wax after surgery to cover the cut ends of the wire are techniques to protect the lips and cheeks from trauma caused by the cut wire ends. Generally the arch wires can be changed approximately 4 to 6 weeks after surgery, at about the same time that the splint is ordinarily removed. It is usually too uncomfortable for patients to tolerate the arch wire change before then. If a palatal splint is in place, it can remain in place because it should not interfere with the arch wire change and the splint can continue to help with maxillary transverse stability. Occlusal coverage splints usually require removal before the arch wire can be changed.

DENTAL ARCH SPACING

The correction of significant anterior tooth size discrepancies may require the creation of space in the upper arch between the lateral incisors and cuspids, and/or lateral incisors and central incisors to ensure a good class I occlusal fit with proper overjet/overbite relation ( Figure 19-4, A ). In the postsurgical management phase, this space must be maintained for subsequent bonding, veneers, or crowns ( Figure 19-4, B ). Do not close the space because this can result in malocclusion. A common postsurgery orthodontic practice is to close interdental spaces. This can create major occlusal problems by downward and backward retraction of the maxillary incisors, resulting in an end-on incisor relation, posterior open bites, downward and backward rotation of the mandible, increased stress on the TMJ, and pain. If these spaces have been closed, the spaces require reopening with forward rotation of the incisors to improve the occlusal fit and subsequent restorative dentistry to eliminate the spaces with bonding, veneers, or crowns.

TOOTH MOVEMENT

Teeth move rapidly for approximately the first 6 months after surgery. Relative to tooth movement, the orthodontist usually can accomplish in 1 to 2 weeks after surgery what took 3 to 4 weeks before surgery. This is because bone metabolism and bone turnover increase substantially after surgery, allowing more rapid bone resorption and apposition in response to orthodontic forces, so the teeth move more quickly. In addition, with segmental maxillary surgery the individual bone segments can move, providing increased flexibility of the teeth and bone segments.

FINISHING ORTHODONTICS

The patient should keep the orthodontic appliances on for a minimum of 4 to 6 months after orthognathic surgery, when appropriate rigid fixation techniques are used, to allow initial bone healing as well as completion of the aligning, leveling, and stabilizing of the occlusion. Four months typically are required to complete the initial postsurgical bone healing phase, when the maxilla and mandible should be skeletally stable. If inadequate rigid fixation was used or the maxillary bone was exceptionally thin, or uncontrolled clenching or bruxism is present, then orthodontic appliances may be required for an extended period. In general, the greater and more complex the required surgical movements and presurgical orthodontic treatment mechanics, the longer the time requirements for the postsurgical orthodontic management. The orthodontist will determine when the occlusion is maximized and stabilized and when the patient is ready for debanding and retainers.

RETAINERS

For patients who have undergone orthognathic surgery, rigid retainers (Hawley type) without occlusal coverage ( Figure 19-5 ) are recommended to provide transverse support to the width of the maxillary and mandibular dental arches, maintain the dental alignment, and allow maximal interdigitation of the occlusion. Occlusal coverage retainers ( Figure 19-6, A ) should not be used because of vertical separation of the occlusion, which can create a malocclusion, usually with open bite situations anteriorly or posteriorly, unilaterally or bilaterally. In addition, occlusal coverage retainers usually are flexible (see Figure 19-6, B and C

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses