Osteomyelitis is an infectious, inflammatory process of bone marrow with involvement of the overlying cortical plates and periosteum. The marrow space provides a conduit and medium for spread of odontogenic pathogens from dental disease, dentoskeletal trauma, or both. Localized osteitis is not osteomyelitis but can become so. Co-morbidities can make the host more susceptible to the risk of osteomyelitis. This is especially true of any systemic process that causes or contributes to vascular compromise on a local, regional, or systemic level, the end result of which is ischemic microvascular disease ( Box 32-1 ).

-

Non-compliance with health care delivery

-

Systemic metabolic compromise, including the following:

-

Age of patient

-

Malnutrition

-

Immunosuppression

-

Congenital or acquired pathophysiologic condition disrupting microvascular perfusion of calcified tissue and investing soft tissue envelope

-

-

Inaccessibility to health care delivery

Other pathophysiologic processes that occur during osteomyelitic onset such as pathogen-induced microthrombus, compartmentalization syndrome resulting from host pathogen interface metabolic byproducts such as gas, and attempted host recovery such as perfusion injury, all add to the exacerbation of the primary insult.

PATHOGENESIS

Osteomyelitis of the maxillofacial region, most specifically the mandible, is due to polyodontogenic flora rather than Staphylococcus aureus , which is the predominant pathogen for the rest of the axial skeleton. Typically the odontogenic microbes become opportunist when introduced unchallenged into the marrow space via tooth debilitation or trauma. These bacteria are usually strep and various facultative anaerobes initially but can change with the host climate and medium maturation of the infectious process.

CLASSIFICATIONS

The methodology by which most clinicians understand a multifaceted disease process is by a classification relative to similar variables. With osteomyelitis these common variables continue to be an ongoing debate. Some authors have classifications based on disease locations. Others base the disease process on suppuration or lack thereof whereas others use hematogenous spread. This author developed a classification and staging of this disease based on a commonly referenced denominator from multiple articles written on osteomyelitis leading to the publication of “50 Year Perspective on Osteomyelitis of the Jaws” in the 50th anniversary of the Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery . That classification system was based on the simple principle of acute versus chronic forms of osteomyelitis as defined by time or presence of disease from initial diagnosis to definitive treatment response less (acute) or greater (chronic) than 1 month ( Box 32-2 ).

- I.

Acute forms of osteomyelitis (suppurative or nonsuppurative)

- A.

Contiguous focus

- 1.

Trauma

- 2.

Surgery

- 3.

Odontogenic infection

- 1.

- B.

Progressive

- 1.

Burns

- 2.

Sinusitis

- 3.

Vascular insufficiency

- 1.

- C.

Hematogenous (metastatic)

- 1.

Developing skeleton (children)

- 2.

Developing dentition (children)

- 1.

- A.

- II.

Chronic forms of osteomyelitis

- A.

Recurrent multifocal

- 1.

Developing skeleton (children)

- 2.

Escalated osteogenic activity (< age 25)

- 1.

- B.

Garré’s osteomyelitis

- 1.

Unique proliferative subperiosteal reaction

- 2.

Developing skeleton (children to young adults)

- 1.

- C.

Suppurative or nonsuppurative

- 1.

Inadequately treated forms

- 2.

Systemically compromised forms

- 3.

Refractory forms (chronic refractory osteomyelitis [CROM])

- 1.

- D.

Sclerosing

- 1.

Diffuse

- a.

Fastidious microorganisms

- b.

Compromised host and pathogen interface

- a.

- 2.

Focal

- a.

Predominantly odontogenic

- b.

Chronic localized injury

- a.

- 1.

- A.

CLASSIFICATIONS

The methodology by which most clinicians understand a multifaceted disease process is by a classification relative to similar variables. With osteomyelitis these common variables continue to be an ongoing debate. Some authors have classifications based on disease locations. Others base the disease process on suppuration or lack thereof whereas others use hematogenous spread. This author developed a classification and staging of this disease based on a commonly referenced denominator from multiple articles written on osteomyelitis leading to the publication of “50 Year Perspective on Osteomyelitis of the Jaws” in the 50th anniversary of the Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery . That classification system was based on the simple principle of acute versus chronic forms of osteomyelitis as defined by time or presence of disease from initial diagnosis to definitive treatment response less (acute) or greater (chronic) than 1 month ( Box 32-2 ).

- I.

Acute forms of osteomyelitis (suppurative or nonsuppurative)

- A.

Contiguous focus

- 1.

Trauma

- 2.

Surgery

- 3.

Odontogenic infection

- 1.

- B.

Progressive

- 1.

Burns

- 2.

Sinusitis

- 3.

Vascular insufficiency

- 1.

- C.

Hematogenous (metastatic)

- 1.

Developing skeleton (children)

- 2.

Developing dentition (children)

- 1.

- A.

- II.

Chronic forms of osteomyelitis

- A.

Recurrent multifocal

- 1.

Developing skeleton (children)

- 2.

Escalated osteogenic activity (< age 25)

- 1.

- B.

Garré’s osteomyelitis

- 1.

Unique proliferative subperiosteal reaction

- 2.

Developing skeleton (children to young adults)

- 1.

- C.

Suppurative or nonsuppurative

- 1.

Inadequately treated forms

- 2.

Systemically compromised forms

- 3.

Refractory forms (chronic refractory osteomyelitis [CROM])

- 1.

- D.

Sclerosing

- 1.

Diffuse

- a.

Fastidious microorganisms

- b.

Compromised host and pathogen interface

- a.

- 2.

Focal

- a.

Predominantly odontogenic

- b.

Chronic localized injury

- a.

- 1.

- A.

CLINIC AND RADIOGRAPHIC PRESENTATION

Clinical signs and symptoms range from pain and swelling to trismus, paresthesia, adenopathy, and malaise. Fistulization is more commonly seen with purulent long-standing osteomyelitic infection and can harbor neoplastic change from inflammatory metaplasia cultures of sinus tracts, which usually show auras and are of little value. Necrotic bone and non-healing hard and soft tissue wound may be in evidence. Paresthesia is a symptom to which the clinician should pay greater attention because not only does it speak to increased intermedullary inflammation, swelling, and pressure, but it may have a terminal end result creating permanent nerve injury and subsequent neuropathic pain, which may be the more prevalent clinical problem faced in chronic osteomyelitis. This neuropathy will be discussed further later in this chapter. Positive laboratory findings are usually typical of those seen with any infectious inflammatory process such as elevated white cell counts (i.e., leukocytosis), elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rates, and positive C-reactive proteins. All of these assays could also be elevated by dehydration and poor oral fluid intake as a result of the infection being located in the jaw and the upper alimentary tract.

Greater attention needs to be focused on the systemic sequela of local and regional oral infection and the infectious inflammatory process influence that has now been directly implicated in such distant organs as myocardium and colon as well as being associated with pre-term birth and lowbirth-weight infants. This would include not only periodontal and pericoronal infection, but also osteomyelitis, especially of the chronic variety. Cultures of wound prior to antibiotic therapy coupled with blood cultures taken at appropriate times (i.e., with febrile fluctuation) should identify pathogens normally only seen with odontogenic infectious processes. Many of these organisms are very fastidious or delicate so cultures must be maintained beyond the usual 3-day lab interval to identify the fragile pathogens. Occasionally there will be unusual pathogens including viruses like HIV or CMV or metastatic embolic infection to teeth-bearing areas of bone because of its unusual intermedullary vascular configuration as identified in case reports, but these are unusual.

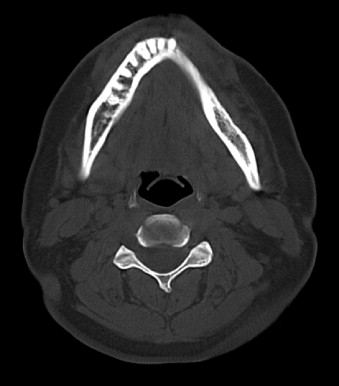

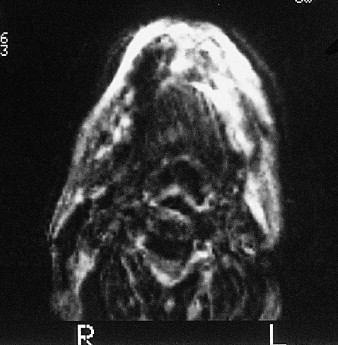

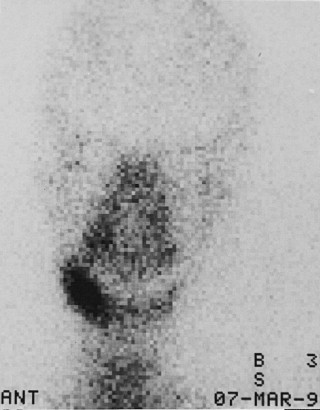

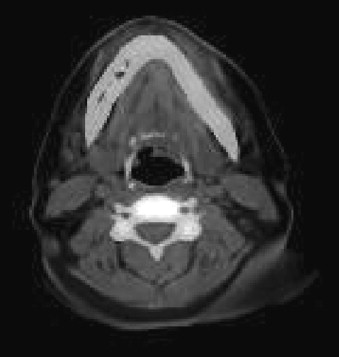

Radiographic evaluation of infectious inflammatory disease is usually in the form of scout film or orthopantogram. This radiograph is more likely to identify risk or causative factors than the disease process itself, especially in the acute phase. Lytic radiolucent areas may be seen; however, the classic radiopaque reaction to infectious inflammatory disease processes is usually not appreciated until later in the more non-acute phase of the disease process ( Figure 32-1 ). CT and MRI both are helpful, with CT imaging giving more resolution to the lytic areas and MRI identifying loss of marrow signal associated with infection, swelling, and inflammation with possible necrosis ( Figures 32-2 and 32-3 ). Triphasic bone scanning includes a flow phase of technetium-99 bone scanning, which identifies areas of osteoplastic-induced bone turnover once this is ongoing, and indium-111 or gallium-67 scanning, which identifies actual infectious inflammatory leukocytic processes, although poor in resolution ( Figure 32-4 ). PET CT with the fluoride isotope is much more sensitive to bone turnover and metabolic change with marked improvement in resolution over old PET scanning, but it is somewhat cost prohibitive ( Figures 32-5 to 32-7 ). Recently cone beam CT has shown possible benefit in the radiologic evaluation and cost analysis.

TREATMENT

Osteomyelitis, whether acute or chronic in nature, still is a surgical disease. Surgical disruption of the infectious foci and organized abscess along with debridement of necrotic tissue and foreign bodies is paramount. As with most typical infectious processes, there is localized immunoregulatory effect by the host to wall off the infectious foci. This is augmented to some degree by the infection itself. Disruption of this infectious architecture is necessary if other adjunctive measures such as antimicrobial therapy are to have a chance to aid in resolution. Several types of surgical intervention recruit and create a heightened inflammatory phase, which allows reperfusion or hyperemia. Hyperemic conditions allow the host immune response to be augmented by antibiotics and to develop therapeutic thresholds in the infection site ( Table 32-1 ).

| Acute Osteomyelitis | Acute Osteomyelitis | Chronic Osteomyelitis |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses