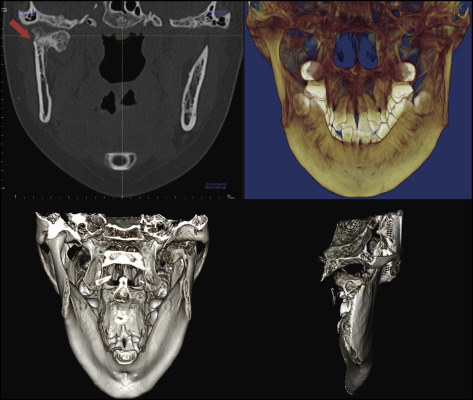

A 15-year-old girl who had a unilateral condylar fracture with severe crowding in both arches was treated with 4 premolar extractions followed by orthodontic therapy with a temporary skeletal anchorage device in the maxillary arch. The total active treatment time was 21 months. Her occlusion was significantly improved by orthodontic treatment, and the range of condylar movement was also improved. Posttreatment records after 30 months showed excellent results with a good stable occlusion. The remodeling process of the condyle was confirmed with cone-beam computed tomography images.

Highlights

- •

Unilateral condylar fracture and severe crowding were treated with temporary skeletal anchorage and first premolar extractions.

- •

Esthetics and function were significantly enhanced after treatment.

- •

The fractured condylar area showed remodeling during the retention stage.

Whereas mandibular fracture has the second highest incidence rate among facial bone fractures, condyle fracture accounts for 29% to 52% of all mandibular fractures, making it the most frequent facial fracture. Nonsurgical treatment has been commonly accepted and recommended for pediatric patients; however, the treatment of choice for a condylar fracture in adults has remained controversial for many years. Currently, the classification system of Lindahl for condylar fractures is most generally accepted and used. According to it, condylar fractures can be divided anatomically into 3 sites: intracapsular (condylar head), extracapsular (condylar neck), and subcondylar region. Furthermore, Lindahl classified the extent of dislocation into medial, lateral, and no overlap or fissure, and condylar head fractures into horizontal, vertical, and compression.

Although a fractured mandibular condyle has shown regeneration similar to its original size in most cases, it can also be associated with deteriorating side effects including mandibular deficiency, temporomandibular joint (TMJ) dysfunction, or facial asymmetry, if not managed properly. Treatment of a condylar fracture depends on various factors including the extent of the injury, the level of the fracture, the size and position of the fractured condylar segment, the degree of dislocation and displacement, the stage of the dentition, the presence of a facial fracture, malocclusion and mandibular dysfunction, and the age and willingness of the patient to have surgery. The treatment options range from conservative treatment consisting of observation, analgesia, and a soft diet, to maxillomandibular fixation or functional appliance therapy, and in some cases surgical intervention. In growing patients, most authors have recommended the conservative approach because of the growth potential of the condyle. This article demonstrates the successful orthodontic treatment of a 15-year-old girl with a unilateral condylar fracture that was treated conservatively. Normal occlusion and jaw movement were achieved, and satisfactory condylar process remodeling and possible repositioning of the temporomandibular fossa through apposition were observed.

Diagnosis and etiology

A 15-year-old girl was referred for an evaluation of orthodontic treatment. Her chief complaint was ectopically erupting maxillary canines. During her orthodontic evaluation, she reported that she had suffered a traffic accident 7 months ago and was in splint therapy. At the emergency hospital, she received immediate therapy consisting of antibiotics, anti-inflammatory analgesics, a soft diet, and physiotherapy (passive and active mouth opening). Clinically, upon opening her jaw, the mandible deviated slightly to the affected right side. She had no temporomandibular disorder symptoms such as pain, restricted jaw movement, joint noise, or other symptoms. During the TMJ evaluation, she did not report muscle or joint pain or other symptoms typically associated with a temporomandibular disorder.

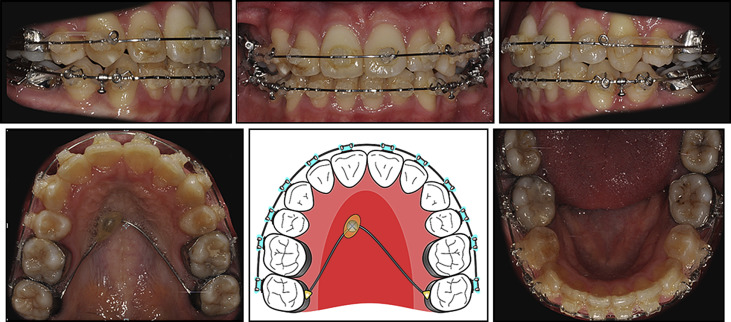

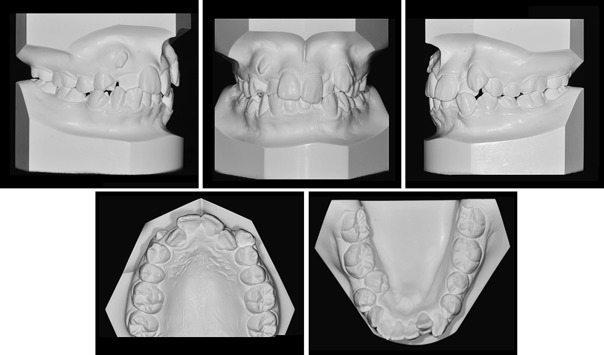

The patient had a mesofacial and Class I appearance. There was no significant facial asymmetry. Intraorally, she had anterior crossbites, a lingually displaced mandibular right second premolar, and a buccally positioned maxillary left canine, and the maxillary right canine was also erupting in an ectopic position. She had a 2-mm overjet and an 80% overbite on her maxillary left central incisor. Her maxillary left central incisor showed more extrusion than did her maxillary right central incisor, and there was canting. She had a Class I molar relationship on both sides. She showed severe crowding in both arches with a deep curve of Spee. Compared with her facial midline, the maxillary dental midline was shifted 1.5 mm to the right, and the mandibular dental midline was deviated 2.5 mm to the right ( Figs 1 and 2 ).

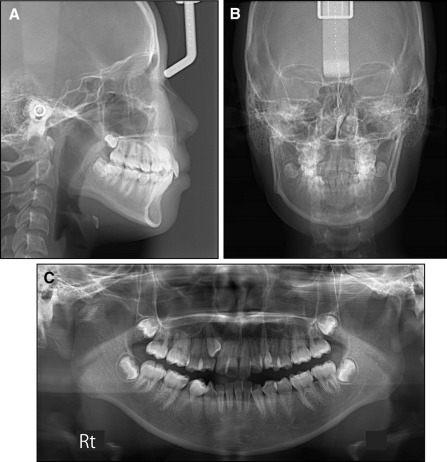

The panoramic radiograph showed an abnormally shaped right condylar head. All third molars were erupting. From a posteroanterior cephalogram and cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) image, the right condyle was found to be fractured at the neck of the condyle and deviated medially with no other alterations of the facial bone structures. The lateral cephalometric analysis indicated a skeletal Class II pattern (ANB, 4.3°) with a normovergent growth pattern (SN-MP, 33.6°). The maxillary and mandibular incisors were proclined (U1 to SN, 114.6°; IMPA, 102.1°) ( Figs 3 and 4 ; Table ).

| Measurement | Japanese norm | Pretreatment | Posttreatment | Postretention |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SNA (°) | 82.0 | 84.2 | 84.1 | 84.6 |

| SNB (°) | 79.9 | 79.9 | 80.6 | 81.3 |

| ANB (°) | 2.0 | 4.3 | 3.5 | 3.3 |

| Wits (mm) | 1.1 | −3.9 | −4.7 | −4.3 |

| SN-MP (°) | 34.0 | 33.6 | 34.1 | 33.9 |

| FH-MP (°) | 28.2 | 26.0 | 26.8 | 26.6 |

| LFH (ANS-Me/N-Me) (%) | 55.0 | 59.0 | 58.5 | 58.6 |

| U1-SN (°) | 104.0 | 114.6 | 107.4 | 107.5 |

| U1-NA (°) | 22.0 | 30.3 | 23.3 | 22.9 |

| IMPA (°) | 90.0 | 102.1 | 93.4 | 93.5 |

| L1-NB (°) | 25.0 | 35.6 | 28.1 | 28.7 |

| U1/L1 (°) | 124.0 | 109.7 | 125.1 | 124.8 |

| Upper lip (mm) | 1.2 | 2.6 | 0.8 | 0.2 |

| Lower lip (mm) | 2.0 | 3.7 | 2.1 | 1.5 |

Treatment objectives

The following treatment objectives were established: (1) observe the remodeling of right condyle, (2) relieve the crowding in both arches, (3) correct the anterior crossbites, (4) improve the deviation upon opening and correct the dental midline, (5) establish Class I canine and maintain Class I molar relationships, (6) obtain normal overjet and overbite, (7) level the curve of Spee, (8) obtain a stable occlusal relationship, and (9) improve the facial and dental esthetics by establishing an esthetic smile.

Treatment objectives

The following treatment objectives were established: (1) observe the remodeling of right condyle, (2) relieve the crowding in both arches, (3) correct the anterior crossbites, (4) improve the deviation upon opening and correct the dental midline, (5) establish Class I canine and maintain Class I molar relationships, (6) obtain normal overjet and overbite, (7) level the curve of Spee, (8) obtain a stable occlusal relationship, and (9) improve the facial and dental esthetics by establishing an esthetic smile.

Treatment alternatives

Condylar fractures in childhood are generally treated conservatively without surgery. Many previous studies have recommended conservative therapy for condylar fractures in pediatric patients. “Conservative therapy” includes a nonsurgical approach with several modalities such as physiotherapy with observation. Open reduction is proposed in certain cases such as severely displaced fractures or when there is a loss of ramus height. Many authors have suggested that in cases without occlusal deviation or other symptoms (such as pain), no immobilization is required, and active physiotherapy with close follow-up is sufficient. Most surgeons favor nonsurgical treatment of condylar fractures because it produces satisfactory results in most patients without increasing the risk of morbidities from surgery. Since our patient was asymptomatic and showed only a slight deviation upon opening, conservative therapy was indicated as the treatment of choice. According to the referenced literature, condylar regeneration and remodeling with adaptive changes will lead to functional restoration of the TMJ. After a discussion with the patient’s oral surgeon, we decided to observe the remodeling of the fractured right condyle during her comprehensive orthodontic treatment. The treatment comprised full fixed appliances along with 2 maxillary first premolar and 2 mandibular second premolar extractions to relieve her severe crowding, with maximum anchorage using a temporary skeletal anchorage device (TSAD) to improve both her occlusal function and esthetics.

Even though the molars were in a Class I relationship, in this patient, the mandibular second premolars were the extraction of choice because the mandibular left second premolar was smaller than the first premolar and was rotated. The mandibular right second premolar was also severely displaced lingually. In addition, we used a tip-edge system, which could create strong anchorage of the posterior segment and produce excessive lingual movement of the incisors. Based on these factors, the mandibular second premolars were selected for extraction.

Treatment progress

Before orthodontic treatment, the patient was referred to a general dentist to verify that there were no cavities and for extraction of the maxillary first premolars and mandibular second premolars. Full fixed 0.022-in tip-edge appliances (TP Orthodontics, LaPorte, Ind) were placed and bonded on both arches for leveling and alignment. To relieve the severe crowding, a TSAD (diameter, 1.6 mm; length, 8.0 mm; OSAS, Tuttlingen, Germany) was placed on the paramedian palatal area and connected to the transpalatal arch that was soldered to the maxillary second molar bands. The mandibular extraction spaces were closed with elastomeric chains from the second molars to circles between the canines and the first premolars on the 0.022-in Australian wire. The minor extraction spaces in the maxillary arch were closed with elastomeric chains from the second molars to circles between the lateral incisors and the canines on the 0.022-in Australian wire.

During the finishing stage, final detailing of the occlusion was accomplished with 0.017 × 0.025-in stainless steel archwires in conjunction with short anterior triangular up-and-down elastics from the maxillary canines to the mandibular canines and premolars worn at night. At the finishing stage, interproximal reduction was recommended to improve the dental midline and the Bolton discrepancy. However, the patient and her mother declined the procedure, leaving her dental midline deviated ( Fig 5 ). Fixed retainers were attached to the maxillary and mandibular anterior teeth. Wraparound removable retainers were also delivered to secure the stability of both arches. Total treatment time for this patient was 21 months.