Esthetics and the conservation of youthful traits are important to most people. Orthodontics plays an essential role not only in maintaining teeth but also in improving the patient’s smile. This is one of the primary reasons why adult patients seek orthodontic treatment: to improve their smile despite their age. This trend has increased over time, and now there is general acceptance of the beneficial effects of adult orthodontics.

SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS IN ADULT PATIENTS

Before discussing adult treatment further, it is necessary to consider the important differences between the treatment of children and adults:

- •

In children the amount and direction of growth determines the treatment plan. In adults there is no residual growth to take advantage of, and the sutures are more closely intertwined.

- •

Adults normally start treatment with fewer teeth than adolescents, especially in the posterior region, and therefore anchorage considerations become more important.

- •

Gingivitis is normally present in children, whereas different degrees of periodontitis are present in adults.

- •

Frequently, adults are more concerned with esthetics and are more demanding than children and adolescents.

- •

Some adults have temporomandibular syndromes that make treatment objectives more difficult to achieve.

It is impossible to treat all patients with a similar approach, especially when dealing with periodontal attachment loss. This issue is often more critical than the chronological age. It is important to remember that the center of resistance is related to the amount of periodontal attachment and indicates the amount and direction of the force that must be applied.

Another factor to consider with adult patients is their past medical treatments, especially those who are or have been taking different medications. This can have a significant effect on the bone turnover, especially in women during menopause. In treating middle-aged women, it is important to consider whether they are menopausal and if they are taking hormonal replacement drugs or being treated with bisphosphonates. Antidepressant or antihypertensive drugs may cause side effects such as dryness of the mucosa and ulceration. These patients require the use of dull-surfaced appliances to avoid lesions affecting the mucosa.

The activation period should be longer and less frequent (6-8 weeks) to allow the patient’s bone time to recover. Loss of 2 mm of root length in a patient with 80% to 90% of periodontal attachment is not the same as in a patient with only 20% attachment. For example, in the patient shown in Fig. 17-8 , the longevity of the tooth would be compromised.

New medical advances have reduced the risks of treating malocclusions in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), osteoporosis, or endocrine disturbances, as well as in long-term users of corticosteroids or immunosuppressants.

TREATMENT USING MINISCREWS

In certain cases, prosthodontists need to upright or intrude molars to normalize the curve of Spee and the occlusal plane. Miniscrews are frequently used in orthodontic treatment as a device for skeletal anchorage when needed.

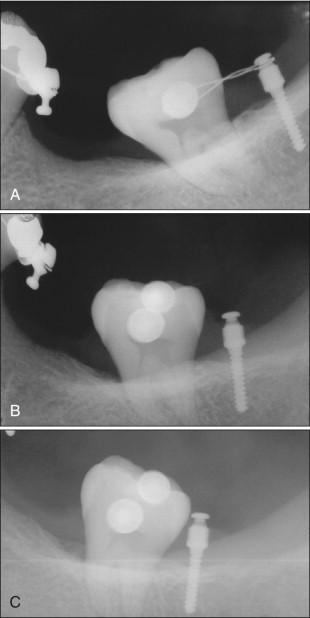

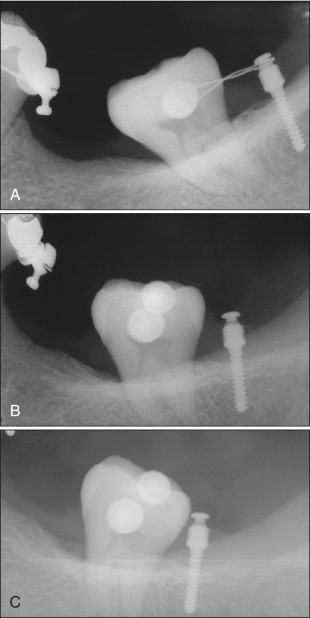

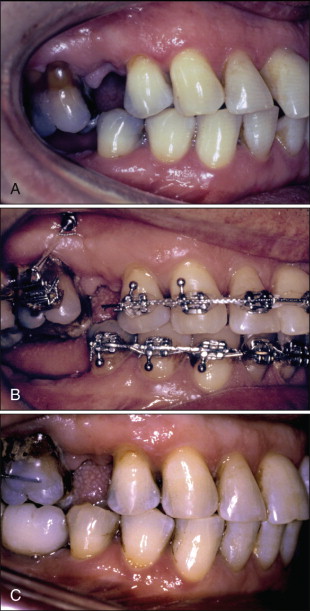

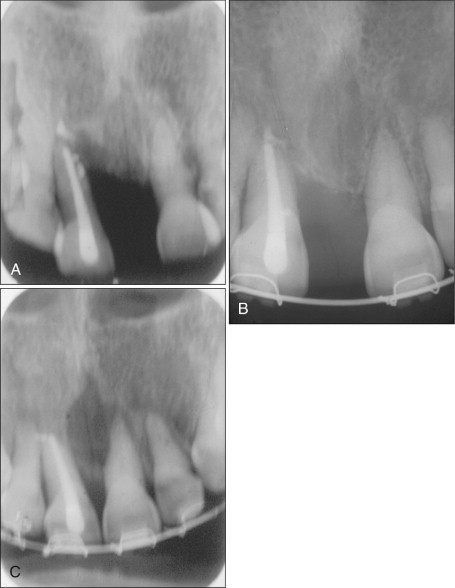

Figure 17-1 shows a 39-year-old patient who sought treatment to correct the position of the left lower second molar. It was decided to use a miniscrew to help in correcting its position, and this case is a good example of how to upright a molar with the use of microimplant anchorage.

A miniscrew also can be effectively used with the overeruption of maxillary molars caused by loss of the opposing teeth, which could create occlusal interferences. Its correction is an essential step before initiating prosthodontic procedures. The intrusion of upper molars is a challenging situation for the prosthodontist. Although a prosthodontic reduction with an endodontic procedure and a crown restoration is an option, the author prefers to solve the problem with microimplants, as shown in Fig. 17-2 . After treatment, pulpal vitality was maintained and periodontal health improved. The occlusal plane discrepancy was corrected without surgical procedures. At the end of the treatment the occlusal space was sufficient to rebuild the posterior occlusion by using an implant prosthesis.

In certain situations the orthodontist must work as a “tissue engineer,” moving teeth to create bone for future implants.

TREATMENT USING MINISCREWS

In certain cases, prosthodontists need to upright or intrude molars to normalize the curve of Spee and the occlusal plane. Miniscrews are frequently used in orthodontic treatment as a device for skeletal anchorage when needed.

Figure 17-1 shows a 39-year-old patient who sought treatment to correct the position of the left lower second molar. It was decided to use a miniscrew to help in correcting its position, and this case is a good example of how to upright a molar with the use of microimplant anchorage.

A miniscrew also can be effectively used with the overeruption of maxillary molars caused by loss of the opposing teeth, which could create occlusal interferences. Its correction is an essential step before initiating prosthodontic procedures. The intrusion of upper molars is a challenging situation for the prosthodontist. Although a prosthodontic reduction with an endodontic procedure and a crown restoration is an option, the author prefers to solve the problem with microimplants, as shown in Fig. 17-2 . After treatment, pulpal vitality was maintained and periodontal health improved. The occlusal plane discrepancy was corrected without surgical procedures. At the end of the treatment the occlusal space was sufficient to rebuild the posterior occlusion by using an implant prosthesis.

In certain situations the orthodontist must work as a “tissue engineer,” moving teeth to create bone for future implants.

TREATMENT OF DIASTEMAS

One of the most common clinical problems seen in adult patients involves closing upper and lower diastemas. For many years, total recovery of the dental papillae after closing the anterior diastema was considered only a chance result. In 1992, however, Tarnow et al. showed that the recovery of the papillae is determined by the distance between the incisor contact point and the crestal bone height. Orthodontists can predictably move the dental contact point to achieve the desired results.

However, to accomplish this, it is necessary first to determine the cause of the diastema. Eliminating the underlying etiology along with closure of the diastema ensures greater stability and less chance of relapse. The malocclusions in which diastemas may be seen can be divided into the following four main groups:

- 1.

Occlusal disturbances caused by premature contacts in the posterior region, which might induce the mandible to move forward during the closing pathway. As a consequence, changes in the normal contact points at the anterior region produce eccentric forces, resulting in diastemas.

- 2.

Loss of teeth in the posterior region, causing anterior teeth to drift distally.

- 3.

Lack of leveling of the occlusal plane.

- 4.

Periodontal problems.

It is crucial to know the true cause creating or increasing the diastema. Otherwise, relapse is highly probable. Additionally, periodontal therapy before, during, and after orthodontic treatment is essential to achieve good and stable results. It is impossible to retain the closure of the diastema when an active periodontal problem is present.

It is well known that similar results can be obtained when the teeth are endodontically treated. Endodontically treated teeth may be less susceptible to apical resorption than vital teeth. In both cases, good recovery of the papillae is obtained. The normalization of the occlusal plane, overjet, and overbite with a normal cuspid and incisor guide is an important prerequisite to achieve long-term stability. Figure 17-3 shows the closure of a large diastema when one of the teeth has been endodontically treated.

Diastemas Resulting from Tongue Thrusting

The presence of the diastema in the anterior region has often been associated with tongue thrusting. It is difficult to determine whether the anterior position of the tongue is responsible for the diastema, a consequence of it, or a combination of both. Nevertheless, when the diastema has been successfully closed, the patient must be sent to a speech therapist to normalize lingual function.

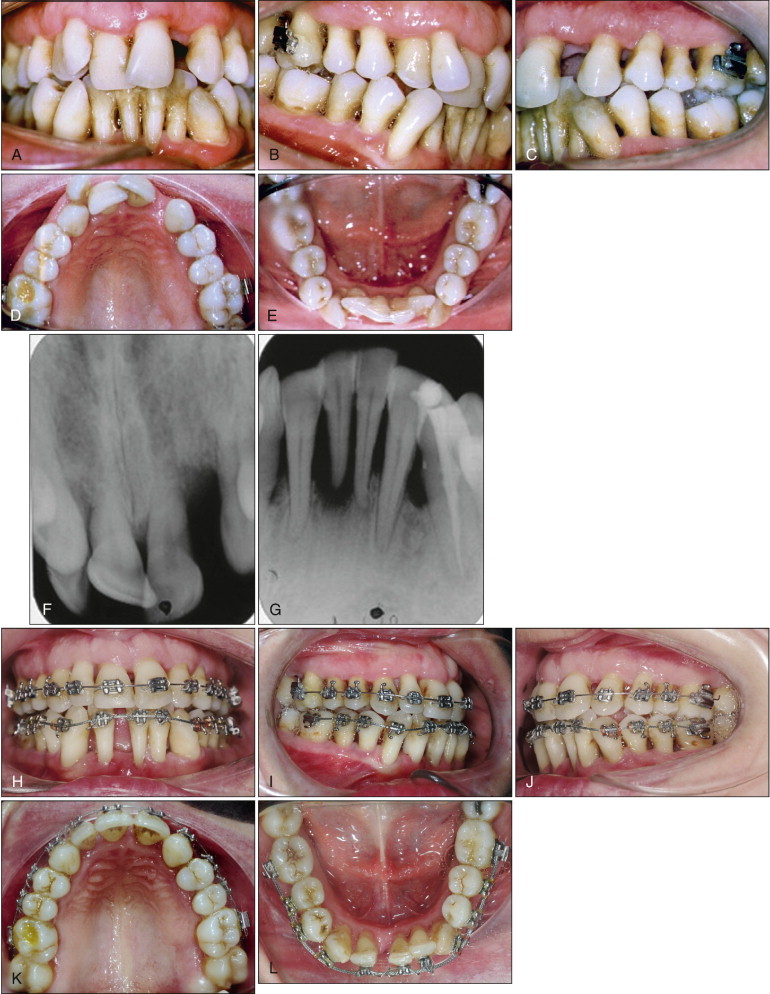

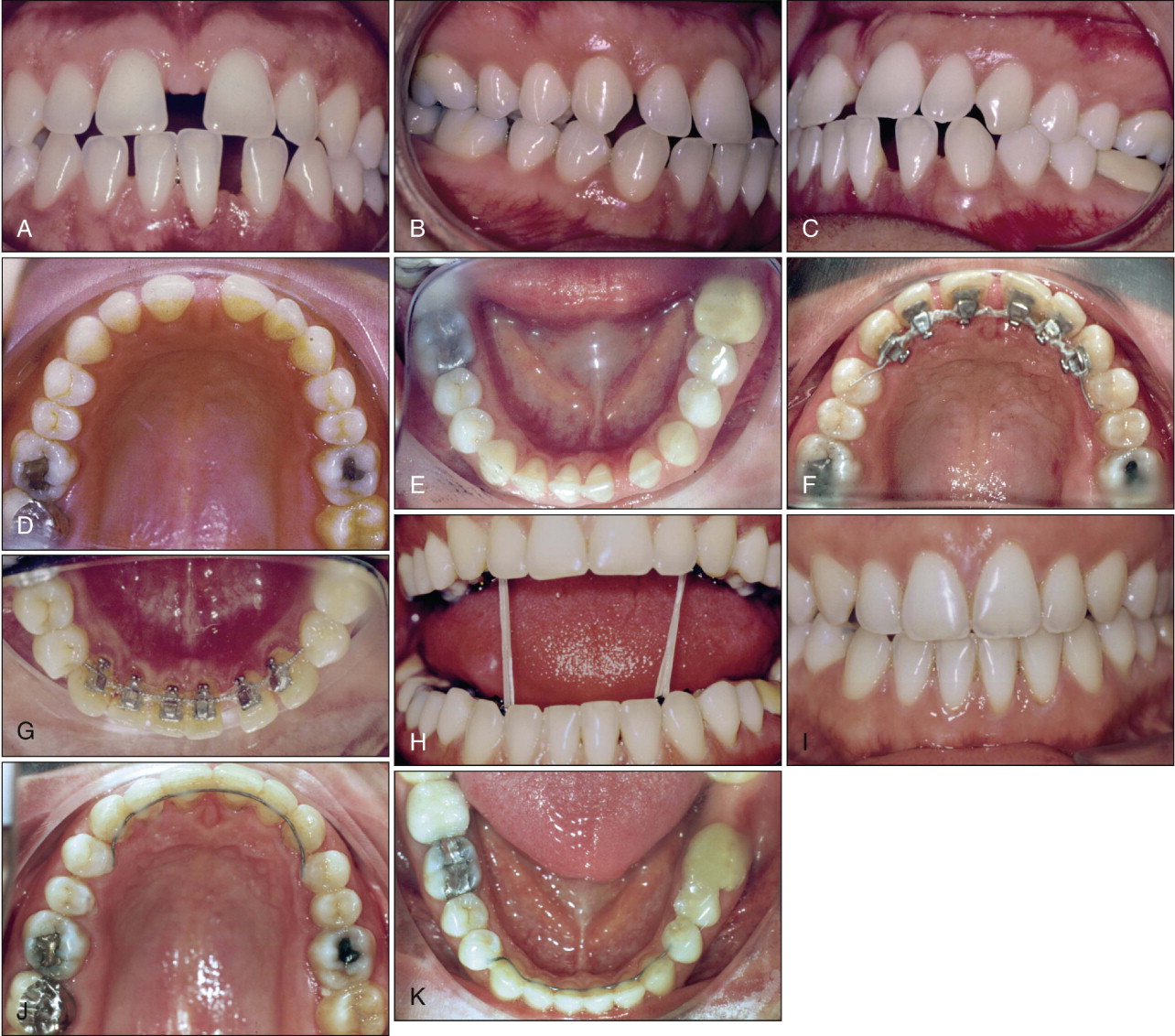

Figure 17-4 shows a 49-year-old man who wanted a second opinion regarding the presence of a diastema between the upper central incisors. His dentist suggested larger central incisor crowns to close the diastema. His dental history indicated that the upper and lower diastemas had improved significantly during the last 2 years, after the extraction of the upper and lower left molars. The lack of interdental papillae was his main concern, as evident from the frontal photograph ( Fig. 17-4, A ).

The extrusion and an increase in the inclination of the anterior incisors were evident and had been worsened by a tongue-thrust habit. As with every treatment plan, periodontal treatment was the first step. It is impossible to move teeth in the presence of bacterial plaque or with active periodontal pockets. In such cases, periodontal monitoring every 2 to 3 months is highly recommended.

Esthetic brackets with a metallic slot were used to diminish friction. It is advisable to begin with low-load deflection archwires (stainless steel .012 × .014–inch Ni-Ti-Cu) to achieve alignment and level the arches ( Fig. 17-4, F-J ). The spaces in the lower arch should be closed first, so as to have the necessary space to close the diastema in the upper arch. To achieve a good result, it is recommended to activate the ligature wires every 4 weeks. It is important to remember that the arch form of each patient requires specific bends. For example, the same arch form used in a severely dolichofacial 12-year-old patient can never be used in a 60-year-old patient with a severe brachyfacial biotype and few teeth. The differences are too great from one patient to another to have preformed archwires for every patient.

Diastemas were closed in the upper and lower arch ( Fig. 17-4, K-M ). The interdental papillae recovered to their normal shape and size. The midline was coincident, and Class I molar and canine relationships were achieved. The occlusal plane was also normalized. The immediate replacement of the missing molars was highly recommended.

Permanent retention with fixed retainers was advised for both upper and lower arches. A Hawley’s plate is not advisable because the palatal acrylic reduces the space for the tongue, which makes it move forward, causing the anterior spaces to reopen. As mentioned previously, treatment by a speech therapist is also required to normalize the position of the tongue. The total recovery of the papillae is only achieved when the gingivoperiodontal tissues are normalized.

Figure 17-5 shows that similar results can also be obtained by using lingual brackets. Pretreatment photographs show a 32-year-old patient with severe diastemas in the upper and lower arches ( Fig. 17-5, A-E ). As evident from the photos, the interdental papillae are absent. Lingual brackets were placed (G7 from Ormco, Orange, Calif.) with a .016-inch titanium molybdenum archwire (TMA). The diastemas were closed with ligature wires ( Fig. 17-5, F and G ). Vertical elastics with lingual brackets were used to improve occlusion ( Fig. 17-5, H ). After 15 months of treatment, the upper and lower diastemas were closed, and the papillae totally recovered ( Fig. 17-5, I-K ). A lower and upper fixed retainer was recommended for avoiding any form of relapse.

TREATMENT OF PATIENTS WITH SIGNIFICANT PERIODONTAL PROBLEMS

Loss of Maxillary Incisor

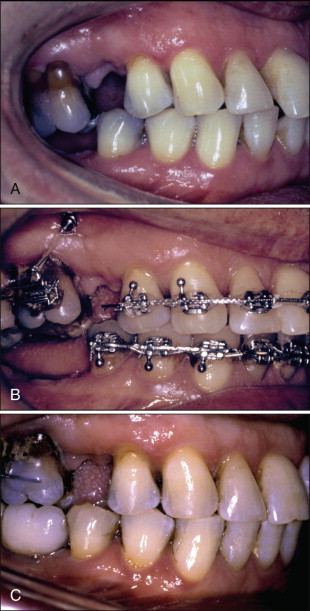

Figure 17-6 shows a 39-year-old female patient whose upper-left lateral incisor was lost because of periodontal problems a few months earlier. She came to the author’s office for a second opinion, referred by the Department of Periodontology at Maimonides University. Her chief complaint was replacement of the upper-left lateral incisor. Her medical history was unremarkable. The pretreatment clinical photographs clearly showed her periodontal problems, especially in and around the incisor region ( Fig. 17-6, A-E ). Significant pathological migration of the anterior teeth was present. Periapical radiographs of the upper and lower incisors confirmed the loss of periodontal attachment ( Fig. 17-6, F and G ).

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses