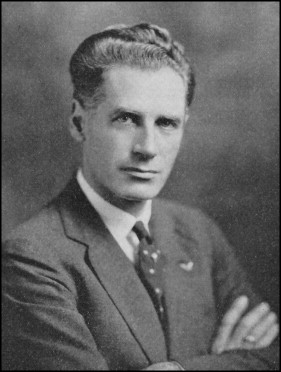

The world is a stage upon which each person plays a part, but only a very few qualify to play leading roles. Martin Dewey was one of the latter.

He was born in 1881 near Kingman, Kansas, where his family had settled after leaving their home near Dowagiac, Michigan, during the great migration which followed the Civil War. (In later years Dr. Dewey made it possible for his widowed mother to spend her summers in Michigan, when he purchased for her a home on the shores of Dewey Lake, near which the family had lived before moving to Kansas.)

Life was rugged on the Kansas plains during Dr. Dewey’s youth. There were no farm price supports in those days, and it was plainly a constant battle to exist. That kind of environment helped to develop the tenacity of purpose and the desire to succeed which were to become so characteristic of Martin Dewey. Dr. Dewey’s choice of a career was probably influenced by the fact that his father was a pioneer dentist.

In 1899, following completion of his preliminary college education at the Wichita (Kansas) Normal School, Dewey enrolled in the Keokuk (Iowa) Dental College. (This school later was consolidated with the University of Iowa.) Following his graduation in 1902, he entered one of the first classes of the Angle School of Orthodontia in St. Louis, Missouri. After completion of his studies under Dr. Angle, he was selected by the latter to teach in subsequent sessions of the Angle School. Dr. Dewey’s connection with the Angle School did not require all of his time so, eager student that he was, he proceeded to earn an M.D. degree by attending medical school in St. Louis. He later discontinued his connection with the Angle School of Orthodontia and established a private practice of orthodontics in Kansas City, Missouri, at a time when the future of orthodontics was highly questionable.

He was a talented and experienced teacher, and it was not long until he became a member of the faculty of the Kansas City Dental School. In this role as faculty member, he soon gained recognition as a teacher, debater, and writer on subjects pertaining to dentistry. His reputation soon radiated and he became an international figure in dentistry.

It was at about this period in his career that Martin Dewey developed into a talented public speaker. He learned to gain and hold the attention of an audience; he attained confidence in himself; he knew full well what he wanted to say, and never was he at a loss for words to say it. In a word, he stood out as a talented man and teacher. Many were heard to observe, after listening to Dr. Dewey in debate, that if he had chosen the profession of Blackstone for a career instead of dentistry, he undoubtedly would have become equally eminent. He was a stickler for facts as being the important thing in any situation; on this basis he later discussed many of the important issues of his profession, and his discussions always reflected clear thinking and an amazing fund of information.

While a member of the faculty of the Kansas City School, Dewey was instrumental in establishing a chapter (Delta Rho) of the Psi Omega dental fraternity. This proved to be not just a social organization, but a vigorous study club where every dental subject was reviewed and discussed, often more interestingly than in the classroom. The subject of orthodontics being his foremost interest, he usually channeled the discussion of nearly every collateral subject, be it biology, embryology, or other subjects, and managed to create a tie-in with an orthodontic application. As a result of the Dewey inspiration, several of the undergraduate students of that period later became specialists in orthodontics and contributed to the creation of orthodontics as a specialty.

There was never enough time to accomplish all that Dewey wanted to do, hence, he was seldom seen without a book under his arm for study. His photographic memory was as amazing as some of the modern exhibits seen on television today.

Time was limited for teaching orthodontics to undergraduate students; however, since the Angle indoctrination and the Angle School experience, Dewey’s mind was on orthodontics and orthodontic teaching so some of his close friends and early students urged him to establish a special course for graduates in orthodontics. The first session of the Dewey School of Orthodontics was held at the Dental School in Kansas City, Missouri, in the summer of 1911. The school was successful; however, it was moved to Chicago, Illinois, in 1917 and then on to New York City two years later. This school continued to hold annual sessions under Dr. Dewey’s personal supervision until his death in 1933. Many of the original orthodontists secured their basic training in this full-time ten-week course. The Dewey students soon organized an alumni group which held annual meetings for a number of years.

In reviewing the professional career of Martin Dewey, one is soon struck by the impact of a preponderance of evidence that here was not only one of the important pioneers of the orthodontic specialty but, in addition, one of the most brilliant and talented men in organized dentistry of all time. He not only served on an infinite number of important committees in organized dentistry, but he was elected president of the American Association of Orthodontists in 1922 and later served as president of the American Dental Association.

For seventeen years he served as editor of the International Journal of Orthodontia (now known as the American Journal of Orthodontics ∗

∗ Later renamed American Journal of Orthodontics & Dentofacial Orthopedics

), which Dr. Dewey and the late Dr. C. V. Mosby of the C. V. Mosby Publishing Company established in 1915. In the early years, it was difficult for the Journal to survive, but Dr. Dewey’s ever-active pen kept the pages filled and his spirit of determination never failed. With the support of Dr. Mosby (even at considerable financial loss), there resulted a journal presently in its forty-third year, which has assembled the most complete record of orthodontic literature in existence today, and which is now the official publication of the American Association of Orthodontists and of all the component societies of the Association.

Dr. Dewey served as professor of orthodontics for short periods at the University of Iowa Dental Department, Chicago Dental College, and the New York College of Dental and Oral Surgery. At the latter, summer sessions of his school were held when he first moved to New York.

Dr. Dewey was the author of several textbooks, including Practical Orthodontics and Dental Anatomy ; he was coauthor, with Thompson, of Comparative Dental Anatomy . All are used as standard texts in many dental colleges even today.

This man, strangely enough, could and did quote Roberts’ Rules of Order off the cuff as glibly as most of us can read it; he knew it from cover to cover. This made him an expert parliamentarian and a leader of professional groups.

A short time before his death Dr. Dewey began the publication of a journal entitled Orthodontic Review , which was designed as an open forum for the discussion and evaluation of current orthodontic literature. However, without his guiding hand the journal was discontinued.

This venture revealed another facet of his character. He was instinctively a critic, a quality which does not make for close friendships and often creates violent prejudices. The pages of Orthodontic Review gave him ample opportunity, without reservation, to comment and disapprove, and this he was amply able to do.

He was a constant student who was never a neutral or a follower. Either he knew the facts and had the ability to prove and present them or, if not, he sought additional knowledge in order to verify his views. He did not make assertions shrouded in doubt, or on the basis of personal opinion. He contended that personal opinions are usually influenced by prejudice and that criticism of a personal opinion or of a theory that cannot be factually supported meets with prompt opposition. Air castles are quite sacred to the builders, even when built upon the sand, and when they tumble and fall the wrath of the builder is heaped upon the critic. Dr. Dewey often found himself an unpopular critic.

He commented that it was of little importance where or how one gained knowledge; the really important thing was whether or not one attained it and how he used it.

Dr. Dewey deplored the plan of some dental schools to abandon the teaching of certain subjects on the presumption that they were not essential in the practice of orthodontics. He thought that the curriculum should be enlarged and expanded, instead of curtailed, and that a more equal balance between technical instruction and the basic sciences was vitally necessary. The fact that dentistry began as a mechanical “trade” has been its greatest handicap to becoming a profession, and Dr. Dewey sought to remove that handicap from orthodontics.

Dewey contended that one’s professional education is never completed, that increased knowledge only widens the opportunity to gain more knowledge, and he thought that the practitioner who presumes to be a specialist (other than in name only) should have a comprehensive understanding of every phase of his profession. Due to this belief, Dewey was quick to oppose the “Arizona Orthodontic Law” since he felt that it limited education and, in reality, was an attempt to divorce orthodontics from dentistry. It was the hope of its sponsors that other states would enact similar laws and that eventually the practitioner would be forced to follow a certain system of treatment in order to qualify for a license. Fortunately, the law was promptly repealed. As Dr. Dewey pointed out, such a law would produce mechanical robots, rather than better orthodontists.

He noted that it was regrettable and most unfortunate that the birth of orthodontics was handicapped by the belief that in order to practice one must be adept in a mysterious mechanical art in which only a few could qualify. Malocclusion was recognized and mechanically treated with some rather vague and conflicting ideas of the many factors which might cause the anomalies. Mechanical appliances became the cure-all remedy although Dr. Dewey often stressed the fact that the orthodontic problem is both a biologic and a mechanical one, and that an orthodontic appliance should always be considered as a necessary evil. Nevertheless, mechanics offered a field day to the gadget-minded practitioner and a very wide opportunity to develop and present personal theories. The perfect appliance was invented before the many factors necessary to the production of normalcy were discussed. Even today, mechanics presumes to dictate to Nature exactly what normalcy should be. Science, a word that is being used rather loosely, is being nudged to move over and give empiricism more room. When Dr. Dewey died a vacancy was created which has never been filled. The forum of debate was his delight–not as a place to discomfort his opponent, as some presume to believe, but rather as a means to find and establish a truth. “Science,” he remarked, “knows no friendship.” During the past twenty-four years it has been apparent that the profession misses his guiding influence and his keenness to detect the flaws and to help erase them.

He believed that a philosophy was, in fact, a truth and never a child of fantasy; that truth does not just occur to support a theory, but that it must precede it. Nothing could be termed a truth if it were in opposition to normalcy in the cycle of growth and development, as we now understand it in life.

In the beginning of what is now termed the modern era of orthodontics there was a growing tendency to secure patents on appliances and gain profits through royalties. This again brought prompt and forceful opposition from Dr. Dewey, who contended that the public needed protection since it eventually paid the extra costs.

On the same principle, he was one of the most active workers in the Dental Protective Organization in the court fight over the “Cast Inlay Episode” when an attempt was made to blackmail the dental profession. He was thirty years ahead of his time in pointing out that the dental profession was losing command if it failed to supervise the commercial dental laboratories; he contended that the laboratories eventually would dictate to the dentist on construction and diagnosis of all prosthetic restorations and finally, through enactment of laws, they could practice “mechanical” dentistry without the aid of the general practitioner. That prophecy is rapidly coming to pass.

Dr. Dewey’s foremost asset was his ability to teach. He had the knack (which few teachers possess) of instilling into his students a desire to find out more about the subject under discussion. His objective was to present a broad outline and give the student an opportunity to think. He was of the opinion that it was important to create interest wherein the student would ask “Why?” instead of accepting everything as factual. It appears that his methods were quite effective, as a majority of his students progressed far beyond their postgraduate days.

There has always been some opposition to the short postgraduate courses; however, it, is doubtful if any of the longer courses available today are an improvement over the original Dewey School after it was moved to New York. He had an unlimited source of talent in that area for special lectures in the medical and dental fields, as well as in all the allied fields. His school compared, in some degree, to preceptorship and apprenticeship training on an intensive level. The total number of lecture hours and the hours of technical training equaled and probably exceeded some of the longer courses. Under his personal guidance, his school system really functioned.

Dr. Dewey was one of the first seven men selected to serve on the American Board of Orthodontics when it was established in 1929. This Board has been most effective in raising the standard of qualifications for the practice of orthodontics.

As to recreation, game bird hunting was his real hobby. He kept several good hunting dogs in Georgia, where he frequently hunted quail in season; however, when time permitted, he enjoyed hunting duck on the Gulf Coast or prairie chicken and pheasant in the Midwest. He was an excellent shot; in fact, he was an expert. When asked why he seldom missed, he replied simply, “I don’t shoot until I get my gun on the bird.” He applied this same method on the lecture platform or in debate. His reserved manner was considered unfriendly by many, even by his associates of many years. Dewey kept himself so busy that he had little time for chitchat and backslapping. If he was glad to see you he would simply say “Hello” and on occasion call you by name. Although he did not smoke or drink, he was the ideal host in his home or on his boat. Those who were privileged to make long automobile trips with him or to join him on frequent hunting journeys were surprised to find an entirely different personality. If there were only two or three in the party he lost his reserved manner, became jovial, and talked constantly, entertainingly, and most interestingly on any topic from astronomy or geology to mumble-peg, sleight-of-hand, or amateur magic. He enjoyed the companionship of the late Dr. Oscar Busby of Texas, who had few equals as a wit in a crowd but who was at the same time a serious and intelligent speaker in a small group discussion.

It is a well-known fact that there are actually hundreds of orthodontic appliances constructed by commercial laboratories for each one that is designed and constructed by a competent orthodontist. The only diagnosis available to the laboratory technician is a plaster cast. Dewey frequently pointed out that the only way to combat this routine was to provide a better and more comprehensive understanding of orthodontics for the undergraduates and to make a greater effort to educate the public in all phases of dentistry.

Dr. Dewey’s failure to get the American Dental Association to accept and sponsor his national advertising program, during his administration as president, was probably the greatest regret of his professional life. The great effort and work that he put into that plan, the necessary travel to all sections of the country, and the many addresses he made upon the project (at a time when he was not physically able to do so) probably contributed to his last illness. The sad and ironic part is that the plan would not have cost the American Dental Association a single cent, although the Association would have had complete supervision of all the published material. The plan would have been handled in much the same manner as presently followed by the American Medical Association, whereby the drug manufacturers, insurance companies, and all who are vitally interested in better health are willing to cooperate and finance the project. Once again Dewey was ahead of his time and, one might add, ahead of his profession.

Even a brief summation of the professional career of this remarkable personality shows that he was a credit to his profession, that he left it progressively better than when he entered it, and that, as a dental educator he had few equals and no superiors. It should be mentioned that on the night of his death, the news was carried on the large moving electric tape atop the Times Building in New York City’s Times Square. The press was well aware of his prominence in his profession and of the fact that he was one of the foremost educators of his time. It was a final and fitting salute, well deserved and fully merited by the former farmboy for his rather long, yet meteoric, trip from Kansas to the “Lights of Broadway.”

[ The 1957 publication includes a bibliography listing over 100 articles written by Dr. Dewey. ]

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses