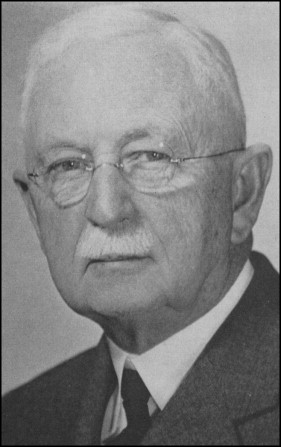

John Valentine Mershon was a simple, kindly, and unpretentious man who was endowed with qualities of mind and heart that marked him as a great personality. As long as there is a specialty of orthodontics, he will be known for his quiet, genial, and generous efforts to help others. His gentle nature won him many friends, from little children to case-hardened colleagues who may not have seen eye to eye with him.

He was born at Penn’s Manor, Pennsylvania, on July 7, 1867, the youngest of the nine children of Onias C. and Amanda Valentine Mershon. He attended the local elementary school and the Model School at Trenton, New Jersey. Having decided to become a dentist, he entered the Pennsylvania Dental College (later merged with the University of Pennsylvania), from which he was graduated in 1889 with the degree of Doctor of Dental Surgery. He served his alma mater as Instructor in Dentistry for some years and engaged in the general practice of dentistry in Philadelphia for nineteen years.

In 1896 Miss Harriet Lane Worrall, member of an old colonial family of Pennsylvania, and Dr. Mershon were married.

When orthodontics became his absorbing interest, Dr. Mershon sought training at the Angle School of Orthodontia. Upon completion of the course of instruction in 1908, he returned to Philadelphia and limited his practice to orthodontics, being one of the first in eastern Pennsylvania to do so. His inquiring, analytic mind and his dedicated desire to best serve his patients soon brought him an orthodontic practice as large and select as had been his in general dentistry.

During most of his years in practice he had some association with teaching. From 1916 to 1925, he served as Head of Orthodontics at the University of Pennsylvania, where he tried to show the undergraduates the need and possibilities of orthodontic treatment. He and his assistant instructors conducted a demonstration clinic; time did not permit teaching the undergraduates how to do the work. It was his aim to present orthodontics from the biologic rather than the mechanistic viewpoint.

Through the years he was interested in the establishment of a Department of Orthodontics with the teaching on a graduate and postgraduate level. When this was finally accomplished in 1945, he was appointed the first guest lecturer.

Dental organizations were in their infancy when Dr. Mershon was graduated, and he was keenly concerned with their betterment. The first society of orthodontists was formed in 1901 by the faculty and the graduates of the Angle School. Membership was restricted to Angle alumni. In 1902, the American Society of Orthodontists was organized, all recognized orthodontists being eligible, and in 1909 the Eastern Association of Graduates of the Angle School of Orthodontia was started. Dr. Mershon was deeply interested and always found time to serve on important committees.

Because of his ability and activity, he was honored by election to the presidency of the American Association of Orthodontists, the Northeastern Society of Orthodontists, the Philadelphia Orthodontic Society (he was its first president), and the Philadelphia Academy of Stomatology.

His professional activities included the following organizations:

-

American Dental Association

-

Pennsylvania State Dental Society

-

First District Dental Society of Pennsylvania

-

Philadelphia Academy of Stomatology

-

The Dental Society of the State of New York (Honorary Fellow)

-

American Association of Orthodontists

-

Eastern Association of Graduates of the Angle School of Orthodontia

-

Northeastern Society of Orthodontists

-

Diplomate of the American Board of Orthodontics

-

Fellow of the American College of Dentists

-

International Association for Dental Research

-

American Association for the Advancement of Science

-

Southern Society of Orthodontists (Honorary)

-

Southwestern Society of Orthodontists (Honorary)

-

Pacific Coast Society of Orthodontists (Honorary)

-

European Orthodontological Society (Honorary)

-

Delta Sigma Delta fraternity

Dr. Mershon was one of the organizers of the First International Orthodontic Congress in 1926 and took an active part in its planning. He served as an honorary president.

For many years he was an active member of the Union League Club of Philadelphia, where he took particular delight in entertaining his many friends. He was always a genial and generous host.

To all these organizations, he gave unstintingly of his time and energy and contributed much to their advancement.

Dr. Mershon initiated the plan by which dental societies provide short refresher and extension courses for their members. He is credited with having organized the first such course in the United States and probably in the world.

In order to evaluate Dr. Mershon’s contributions to advancement, one has to consider the state of orthodontics over a half-century ago. At that time, the health service professions and, to an appreciable extent, the laity were questioning whether teeth could be safely moved to new positions. Would the pulps remain vital? Would the uncompleted roots of growing teeth be bent or the apical ends be prevented from normal formation? Would the bony structure of the alveolar process be strong, and would teeth moved by orthodontic means be retained as long? Would appliances not increase dental caries? Would irritation of gum margins during treatment not predispose to pyorrhea? Could orthodontic treatment be given without causing too great a physical or nervous strain on the young patient? Many dentists and physicians were skeptical and the procedure was too new to permit positive statement.

The pioneers of that uncertain era were truly the missionaries of orthodontics. Their problems and discouragements were many; they had to face a critical profession and a doubting public which had to be convinced of the practicability of orthodontic procedures by successful results in treatment.

Even though a few of the better thinkers spoke of the importance of embryology, histology, anatomy, physiology, and proper nutrition, their knowledge was not well enough classified for much clinical application. To their credit, it must be noted that the programs of orthodontic meetings, from the very beginning, listed papers on biologic subjects. In addition, scientists in collateral fields were procured, and they presented masterful papers that contained much of practical value. The clinicians of that period, however, were not sufficiently prepared in the basic sciences to apply this to any great extent in everyday practice. How to Move Teeth was the urgent problem, and many and varied were the mechanisms devised.

The early appliances were crude and cumbersome, they interfered with speech, and they required weekly or more frequent adjustments which usually caused discomfort and often soreness of the teeth for twenty-four hours or more. Appliances removable by the patients were frequently taken out of the mouth between appointments and carried in pockets, often becoming bent, broken, and sometimes lost.

For the most part, these removable appliances were supplanted in the first decade of limited practice by the so-called “fixed” appliances. The patient could not remove these without breakage. At first they consisted mostly of the Angle labial “E” arch with a nut and threaded end, supported by “D” bands clamped to molar teeth by means of a nut and bolt. Movement of the teeth was brought about by ligatures of metal, silk, linen, or cotton lashed to the teeth to pull them toward the arch and also by tightening the nut. These ligatures had to be renewed weekly. Cleanliness was difficult to maintain.

Dr. Mershon is known to be one of the earliest clinicians who recognized the essential importance of applying biologic principles to the diagnosis and treatment of malocclusion. He was deeply concerned because the appliances then in use lacked these qualities. He sought an appliance that would move teeth by means of a gently continuous pressure and that would not retard growth when the pressure limit of the appliance had been reached. He was well aware that jaws and teeth, in the main, develop downward and outward.

Therefore, he desired an appliance which, from the inside of the growing dental arch, could be so applied that it would not interfere with downward growth and at the same time would not retard outward growth beyond the limit of elastic pressure of the appliance. In short, the teeth could continue to grow beyond the action of the appliance when Nature so ordained. He intended to allow Nature to proceed in growth without orthodontic limitation.

To this end, Dr. Mershon conceived a new principle in appliance action and originated and developed the removable lingual arch, combined with a treatment philosophy and appliance therapy that have continued in use without basic change for a greater number of years than has any orthodontic appliance except the plain labial arch. He also used the plain labial arch in his treatment. However, he gradually modified the plain labial arch to finer-gauge wires to obtain over-all elasticity. He also adopted a perpendicular spring loop to press against the buccal tubes for forward movement.

In his quiet, careful manner, he began to develop the Mershon technique soon after he limited his practice in about 1908, gradually improving the technique as his experience suggested. At first it was shown modestly to two or three of his most respected colleagues. He then gave private clinics to a few more, later inviting them to his office to see what he was able to accomplish with it in the patient’s mouth. The construction of the appliance was taught to a few others who were eager to try it, some of whom soon became enthusiastic in praise of its superior qualities. All the while, he was using his knowledge of physiologic function and observing its effect upon the growing structures supporting the teeth. He discussed his clinical problems with fellows of the University faculty in the biologic sciences and gained much guiding help from them.

A little while later he was induced to give demonstrations at orthodontic meetings, but it was not until 1916 that he presented his first paper, which was published in the International Journal of Orthodontia in April, 1917. As might he expected for so radically different a principle of appliance therapy, it brought forth a veritable storm of opposition from the labial arch, clamp-band, and ligature group.

However, other orthodontists began to use the new technique. Requests for instruction were so insistent that Dr. Mershon asked a group of orthodontists to come to Philadelphia for a week of instruction. He insisted on doing this without fee to help his colleagues in the art and science of orthodontics for the welfare of the patient. By invitation, and sometimes without it, specialists continued to visit him in his office, where he gave freely of his time and talent in showing his results and in giving instruction with gleeful enthusiasm. His visitors became so numerous that they began to interfere with the orderly conduct of his practice.

Therefore, he offered to teach privately organized groups. Three such groups were taught in different sections of the country. Then, in 1926, he was invited by the president of the New York Society of Orthodontists (now the Northeastern Society of Orthodontists) to present a course to a group of forty of its members. He was accorded the facilities and the cooperation of the Department of Orthodontics of Columbia University. He consented upon the condition that no charge be made for the course. He and his two capable assistants gave a week of their time without pay. The course was an unqualified success; the enthusiasm and gratitude of the class were touching. His quietly inspiring manner of teaching had a stimulating influence on his students that instilled a profound desire for self-improvement. Many of those who took this course, given more than thirty-two years ago, are continuing to use the Mershon removable lingual arch therapy as a standard part of appliance treatment. The demand was so great that he was called upon repeatedly to give his course of one to two weeks’ duration under University discipline at Columbia.

This technique had as one of its advantages the obviation of pain during and following treatment adjustments. Another great advantage was the infrequency of treatment appointments—monthly appointments were the rule, and often these were for only a prophylaxis treatment and inspection of appliances. Adjustments frequently were not needed more than once in eight weeks and sometimes not for longer periods since natural growth was not retarded. The appliance was inconspicuous, it did not interfere with speech, and it did not increase the danger of dental caries. Dr. Mershon was not a believer in the early treatment of deciduous arches, but his appliance has been found by others to be the appliance best adapted to the treatment of deciduous and mixed dentitions and it is especially useful in space maintenance.

Dr. Mershon had virtually a missionary zeal regarding the need to convince both the profession and the public that routine extraction of teeth in orthodontic treatment was very harmful. To him, each face was individual and could not be made to conform to a set pattern.

About 1920 he was instrumental in having the University of Pennsylvania invite the teachers of orthodontics in university dental schools to a seminar of one week’s duration. The sessions dealt with the growth and development of the head, face, and individual normal in dentition and physiognomy. He had an artist’s appreciation of a balanced face, of the infinite variety of forms which this balance can take, and of its tendency to change as age advances. The attendance at this seminar was large, the sessions were enlightening, and all felt well rewarded and deeply grateful.

Dr. Mershon also pioneered in bringing impacted teeth into place and in closing spaces where permanent teeth were congenitally missing. Especially noteworthy were the results that he obtained in mouths with as many as six or eight congenitally missing teeth.

Two important facts must be recorded: First, Dr. Mershon positively insisted on teaching his courses without remuneration to keep tuition low so that it would be easier, especially for the younger orthodontists, to take these courses. This generosity was shared by his able assistants. Second, he refused to have the lingual appliance patented for the purpose of reaping royalty on the broad ethical principle that a dedicated worker in the health services should contribute unselfishly of his talent for the welfare of all people.

It can truly be said that Dr. Mershon’s greatest contribution to orthodontics was in the field of education. Furthermore, it is safe to say that, in his time, no orthodontist taught as many fellow orthodontists or taught more generously than did Dr. Mershon. Enrolled in his courses were students from all parts of the United States as well as from Canada, Europe, Cuba, South America, and the Orient. Thus, the influence of his teaching was world-wide. Humanity was enriched by his life and work.

In recognition of his beneficent contributions, Dr. Mershon was given the following awards:

-

The Jarvie Medal and Fellowship by the Dental Society of the State of New York in 1930.

-

Doctor of Science (Honorary) by the University of Pennsylvania in 1933.

-

The Albert H. Ketcham Memorial Award by the American Board of Orthodontics and the American Association of Orthodontists in 1937. (Dr. Mershon was the first recipient of this, the highest award within the power of orthodontics to bestow.)

Many of us remember some of his simple but potent statements that were stressed to all his students:

“It is the VITAL PROCESSES in a developing child that cause teeth to change their positions and not the appliances.”

“You can move teeth to where you THINK they belong; NATURE will place them where they will best adapt themselves to the rest of the organism.”

He had a deep concern about the possible psychopathic effects of uncorrected malocclusion. He did not think of the mouth alone but of the individual patient —mental, physical, and emotional. This deep desire to prevent personality problems reflected his love of humanity.

It was not all work and no play, so “Jack” was not dull. He was a lover of Nature and spent as much of his leisure time as possible in the open. For many years he was an enthusiastic golfer, and he consistently played in the low eighties. He was also fond of deep-sea fishing from his own able cruiser. He took pleasure in having his friends join him on Chesapeake Bay fishing trips. He attributed his rugged good health and longevity—86 years—largely to out-of-doors recreation.

“Uncle John,” as he will always be affectionately known to his students and friends, was a genial man with a ready twinkle in his kindly eyes and a humorous story on his smiling lips. He was a sincere and generous man, never self-seeking, and always devoid of showmanship. He was happiest when helping others, and he received his ample reward in the consciousness of having been of service to his colleagues, to his many patients, and to humanity. It can truly be said that he lived by the Golden Rule. His greeting of life may well be expressed by the words of Ella Wheeler Wilcox:

So many gods, so many creeds,

So many paths that wind and wind;

While just the art of being kind

Is all the sad world needs.

Silver-haired and ruddy-checked Dr. Mershon, who died in 1953, can never be replaced in the affection of his students and friends. When an intense desire to serve humanity is accompanied by an able, quiet, genial personality, the result can mean a great man. Such was John Valentine Mershon.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses