Chapter 45 Open tongue base resection for OSA

1 INTRODUCTION

Surgical treatment of sleep disordered breathing can be difficult for both the patient and the surgeon. The most common surgical treatment for the disorder, uvulopalato-pharyngoplasty, is effective as a stand-alone procedure less than half the time,1 and though the tongue base is recognized as a significant contributing factor in many if not most cases of, obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) it is not often treated sufficiently, for two main reasons: first, most surgeons are not trained to treat this area; second, the results of many of the available procedures for tongue base obstruction are often unpredictable.

Case reports of tongue base surgery for obstructive sleep apnea date back to the 1980s,2,3 but it was Fujita4 in 1991 who is credited with the first significant work in this arena. He resected the midline of the tongue base transorally with a laser, as discussed elsewhere in this atlas; other variations on this type of procedure have since been published.5–8

This was the rationale that led Chabolle to develop a novel technique for the treatment of sleep apnea-related tongue base obstruction. First published in the English literature in 1999,9 his tongue base resection with hyoepiglottoplasty (TBRHE) employs an open suprahyoid dissection of the tongue base through the midline of the neck with identification of the hypoglossal/lingual neurovascular bundle, coupled with a full thickness resection of 24+6 g of tongue base extending as far laterally as the palatoglossal folds. This wide excision is afforded by the dissection and lateral retraction of the hypoglossal nerve and lingual vessels, with resection of the tongue base tissue deep to and lateral to them. The procedure concludes with hyoid advancement to the lower border of the mandible and shortening of the suprahyoid musculature. Because of the aggressive nature of the procedure, TBRHE also includes a temporary tracheotomy. The procedure can be combined with UPPP for one-stage OSA treatment, which was reiterated by Sorrenti et al.10 in a 2006 article documenting additional experience with this procedure.

2 ANATOMY

Because this surgery in essence is a transcervical suprahyoid dissection of the tongue base, it is important to review some salient points of the region’s anatomy, particularly as it relates to the neurovascular structures. The first muscles encountered through the incision are the fan-shaped mylohyoid muscles separated by a relatively avascular midline raphe. The digastric muscles are located more laterally in the surgical field, just superficial to the mylohyoids.

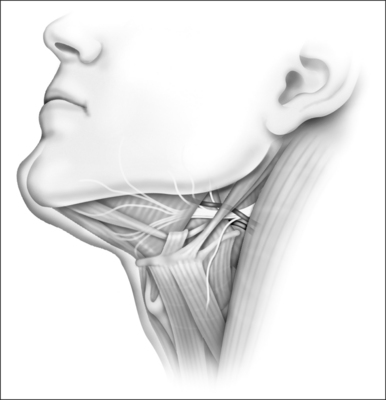

At the lateral aspects of the mylohyoids are the hyoglossus muscles, arising from the greater horn of the hyoid. These fibers run at a roughly 60° angle to the fibers of the mylohyoid. The importance of the hyoglossus muscles is their relationship to the tongue’s neurovascular supply. As shown in Figure 45.1, the hypoglossal nerves and the lingual veins course superficial to the hyoglossus muscles. They are readily seen after releasing the mylohyoid and geniohyoid muscles from the hyoid bone during the surgery. The lingual artery courses deep to the hyoglossus muscle and emerges along its anterior border to parallel the hypoglossal nerve and lingual vein on each side as they enter the tongue base. Also noteworthy is the fact that the hypoglossal nerve is not just a solitary cable that passes over the hyoglossus on its course to the tongue base; it instead gives off a number of small fibers to the portion of the tongue base that is to be resected, which must be divided during the procedure.

3 PRESURGICAL EVALUATION

In addition to these usual cephalometric parameters, Chabolle9 has published other radiographic criteria that he uses to define abnormalities of tongue size and hyoid position, or the ‘hyolingual complex’. This includes measurement of tongue surface area via a T1-weighted mid-sagittal MRI; hyolingual complex abnormalities documented on this MRI include total lingual surface area greater than 28 cm2 and submandibular lingual surface area greater than 4 cm2. The other criterion used by Chabolle is a cephalometric measurement of a quadrilateral space defined as follows: posteriorly by the posterior pharyngeal wall, inferiorly by a perpendicular line extending from the posterior pharyngeal wall to the most anterosuperior point of the hyoid body (H point), anteriorly by a line between H and the posterior nasal spine (PNS), and superiorly by an extension of the line joining the anterior nasal spine to PNS, starting from PNS to the posterior pharyngeal wall. Chabolle contends that a value of more than 25 cm2 within this quadrilateral oropharyngeal space is consistent with hyolingual complex abnormalities.

4 RESULTS

Only two published papers were available by the time of this writing for review. The first of these, by Chabolle,9 details results on 10 patients treated from 1994 through 1997. All underwent full thickness TBRHE with a mean resected lingual volume of 24+6 cm2, as measured by the displacement method. All patients underwent concurrent tracheotomy, with decannulation after a mean of 7+2.5 days. Eight of the patients underwent concurrent primary or revision UPPP and three had concurrent septoplasty and turbinectomy. Overall surgical success, as defined by the usual criteria of postoperative Apnea/Hypopnea Index (AHI) <20 and reduction in the preoperative AHI by 50% or more, was 80%. The mean AHI improved from 70 to 27. Other indices, including subjective snoring and daytime somnolence, likewise improved in all but one patient. Lateral cephalometry showed elevation of the hyoid by a mean distance of 11.5+7 mm (2–26 mm), and this hyoid position remained stable at 3 months despite removal of the hyoid suspension sutures in three patients up to 3 months postoperatively. Oral feeding began at 15+4.5 days, and patients remained hospitalized for 19.5+4 days. No clinical abnormalities with lingual mobility, speech, or swallowing were encountered, and there was no postoperative bleeding. There were five neck abscesses in the first six cases, and these were felt to be related to the use of non-absorbable rather than absorbable sutures for the hyoid suspension in those patients.

Sorrenti10 has published data on 10 additional patients treated from 2001 to 2005. All of these patients underwent concurrent UPPP and TBRHE with concurrent tracheotomy, with decannulation after a mean of 7+3 days. The volume of resected tissue was not reported. Success, again defined by the usual Polysomnography (PSG) criteria, was 100%. The mean AHI decreased from 54.7+11.5 to 9.4+5.4 and the mean low saturation improved from 77%+6.2 to 90.7+3. The hyoid position improved by a mean of 12.1 cm, as measured by the cephalometric change in the mandibular plane to hyoid distance, which improved from 30.4+4.1 cm preoperatively to 18.3+2.4 cm afterwards. The mean hospital stay was 16+2 days and oral feeding began at 13+2 days. There were no infections or postoperative bleeds. Barium swallow examinations were done 6–19 months postoperatively, with abnormal results noted in three patients, including premature spillage over the tongue base, vallecular pooling, and incomplete epiglottic excursion, but there was no penetration or aspiration. All patients resumed a normal diet and the patients’ families reported no subjective changes in speech quality.

My data11 are likewise encouraging. At the time of writing, this includes 26 patients treated from 2000 through 2006. Of these, 14 were treated with TBRHE alone for isolated tongue base obstruction (13 had undergone apparently successful UPPP and one had a normal palate on exam); seven patients with both palatal and tongue base obstruction underwent concurrent TBRHE with UPPP. All of these 22 full thickness TBRHE cases included concurrent tracheotomy. An additional five patients have undergone extramucosal tongue base resections without tracheotomy.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses