Chapter 15 Perioperative and anesthesia management

1 INTRODUCTION

As the population in the United States becomes more obese every year, the incidence of obstructive sleep apnea/hypopnea syndrome (OSAHS) is also increasing. In the general population, the incidence of OSAHS is 2% in women and 4% in men.1 An increase in the body mass index (BMI) of one standard deviation increases the likelihood of co-existing OSAHS by a factor of 4.1 In the morbidly obese population, the incidence of OSA is 3% to 25% in women and 40% to 77% in men.2 Conversely, 90% of OSAHS subjects have a BMI greater than 28 kg/m2. Some subjects have severe (BMI=35 to 39 kg/m2) and even morbid (BMI=40 kg/m2) obesity.

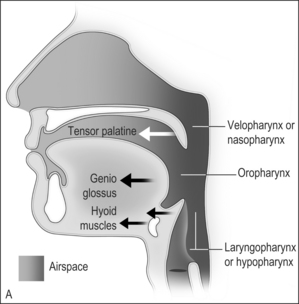

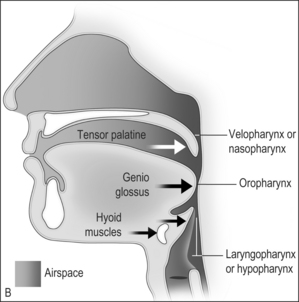

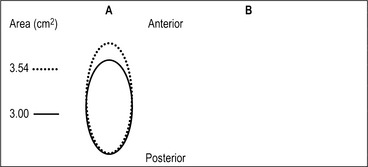

The airway obstruction in OSAHS patients is due to a decrease in the upper airway muscle tone during sleep and airway narrowing due to the deposition of adipose tissue in pharyngeal structures. The structures that may increase in size due to deposition of fat are the uvula, tonsils, tonsillar pillars, tongue, aryepiglottic folds and the lateral pharyngeal walls (Fig. 15.1). The deposition of fat in the lateral pharyngeal walls not only narrows the airway, but also changes the shape of the pharynx. The normal shape of the pharynx with a long transverse (lateral) and a short anterior–posterior axis changes into an ellipsoid with a short transverse and a long anterior–posterior axis. This change in shape makes the action of the anterior pharyngeal dilator airway muscles (tensor palitini, genioglossus, and hyoid) less efficient (Fig. 15.2).3

Patients with diagnosed OSAHS may come to surgery for either OSAHS corrective surgery or for some other procedure. In addition, many patients coming for surgeries other than OSAHS correction may have undiagnosed OSAHS. Respiratory outcomes during the perioperative management of patients with OSAHS are a major concern for anesthesiologists. The inability to tracheally intubate the patient, respiratory obstruction soon after tracheal extubation at the end of the procedure, and severe respiratory depression and respiratory arrest after the administration of sedatives and narcotics are the biggest concerns.4

Recently, the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) developed practice guidelines for the perioperative management of patients with OSAHS.5 These guidelines proposed a scoring system, which can be used to estimate whether a patient is at increased risk for perioperative complications from OSAHS (Table 15.1). The scoring system depends upon three factors: (1) the severity of OSAHS disease; (2) the invasiveness of the surgery and anesthesia; and (3) the requirement for postoperative opioids. The estimation of perioperative risk is based on the overall score; patients with an overall score of 5 or greater have an increased risk of perioperative complications.

Table 15.1 Scoring system for calculation of perioperative risk in patients with OSAHS‡

|

A. Severity of sleep apnea based on sleep study (or clinical indicators if sleep study not available). Point score ______ (0–3).*†

|

Estimation of perioperative risk is calculated as follows: Overall score=the score for A plus the greater of the score for either B or C.

* One point may be subtracted if a patient has been on CPAP or NIPPV before surgery and will be using his or her appliance consistently during the postoperative period.

† One point should be added if a patient with mild or moderate OSAHS also has a resting PaCO2 greater than 50 mm Hg.

‡ Patients with a score of 5 or 6 may be at significantly increased perioperative risk from OSAHS. Modified from Gross JB, Bachenberg KL, Benumof JL, et al. American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Perioperative Management. Practice guidelines for the perioperative management of patients with obstructive sleep apnea: a report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on perioperative management of patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Anesthesiology 2006;104(5):1081–93, with permission.

2 PREOPERATIVE ASSESSMENT OF THEPATIENT

A thorough physical examination of the patient is essential. Many OSAHS patients have several co-existing diseases due to hypoxic episodes and obesity. Careful examination of the cardiovascular system should be done. Bradycardia occurs during apneic spells due to hypoxia and reverts to baseline during and after arousal. In about half of the patients, long sinus pauses, second-degree heart block and ventricular arrhythmias occur. When arterial oxygen saturation (SaO2) decreases below 60%, the severity of the bradycardia and the onset of arrhythmias markedly increase.6 Many patients develop both systemic and pulmonary hypertension. Systemic hypertension is present in half the patients due to repetitive increases in sympathetic tone during each hypoxic/hypercapnic arousal event.7 Pulmonary hypertension has several possible etiologies.

Special attention must be paid to the airway of the patient. In general, obese patients are more difficult to tracheally intubate.10 Since many OSAHS patients are obese, the same principles should be applied when securing the airway of an OSAHS patient. These patients have a large tongue and a thick neck. The probability of difficult tracheal intubation is 5% when the neck circumference is 40 cm whereas the probability increases to 35% when the neck circumference is 60 cm.11 The fact that the excess pharyngeal tissue that is deposited in the lateral walls of the pharynx may not be visible on routine examination is another cause for an unanticipated difficult tracheal intubation. During laryngoscopy, the commonly seen excessive adipose tissue in the interscapular region (‘buffalo hump’) causes malalignment of the oral, pharyngeal and tracheal axes. In addition, since these patients are more prone to aspiration of gastric contents, the Sellick maneuver (cricoid pressure) used during induction of anesthesia before tracheal intubation may also misalign the axes.12 These misalignments can interfere with the ‘line of sight’ and make visualization of the larynx more difficult.

Whether tracheal intubation should be performed with the patient awake or under general anesthesia must be individualized on the basis of a methodical, complete airway examination (Table 15.2). Thus, a multivariate airway risk index should be performed.13 This index identifies several criteria including:

Table 15.2 Components of the preoperative airway physical examination

| Airway examination component | Non-reassuring findings |

|---|---|

| Length of upper incisors | Relatively long |

| Relation of maxillary and mandibular incisors during normal jaw closure | Prominent ‘overbite’ (maxillary incisors anterior to mandibular incisors) |

| Relation of maxillary and mandibular incisors during voluntary protrusion of mandible | Patient cannot bring mandibular incisors anterior to (mandible in front of) maxillary incisors |

| Interincisor distance | Less than 3 cm |

| Visibility of uvula | Not visible when tongue is protruded with patient in sitting position (e.g. Mallampati class greater than II) |

| Shape of palate | Highly arched or very narrow |

| Compliance of mandibular space | Stiff, indurated, occupied by mass, or non-resilient |

| Thyromental distance | Less than three ordinary finger breadths |

| Length of neck | Short |

| Thickness of neck | Thick |

| Range of motion of head and neck | Patient cannot touch tip of chin to chest or cannot extend neck |

This table displays some findings of the airway physical examination that may suggest the presence of a difficult intubation. The decision to examine some or all of the airway components shown in this table depends on the clinical context and judgment of the practitioner. The table is not intended as a mandatory or exhaustive list of the components of an airway examination. The order of presentation in this table follows the ‘line of sight’ that occurs during conventional oral laryngoscopy.

2.1 PREMEDICATION

Sedatives and narcotics have a propensity to exacerbate the sleep-related apneic episodes and may impair life-saving arousal in patients with OSAHS. Benzodiazepines and barbiturates preferentially decrease neural input to the upper airway dilating muscles, leading to airway obstruction.16 Even small doses of narcotics given intravenously or epidurally can cause severe airway obstruction and apnea.17,18 Administration of a combination of sedatives and narcotics can be disastrous. Anxiolytic drugs such as midazolam should only be administered when close monitoring of the patient by appropriate personnel is possible. This means that the drug should not be given until the patient is about to enter the operating room for surgery. Because of the increased incidence of aspiration of gastric contents, an antacid and/or metoclopramide should be given to decrease the gastric acidity and volume. Glycopyrrolate to reduce oral secretions and dexametasone to reduce airway edema and nausea and vomiting are generally administered.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses