Temporomandibular joint (TMJ) disorders are a diverse collection of problems involving the joint itself and/or the surrounding masticatory system. This masticatory system includes the muscles of mastication, their nerve supply, the surrounding afferent neural tracts, central oromotor control, and the maxillary and mandibular dentoskeletal relationship. Given this diversity and the complex cause of the disorders, management is equally diverse. Treatment regimens can be divided into two broad categories: surgical and nonsurgical management. Surgical modalities will be discussed elsewhere in this text.

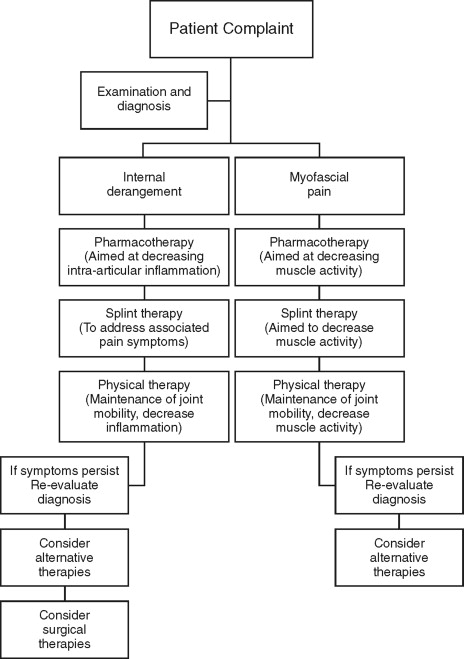

Accurate diagnosis of the particular TMJ disorder is paramount in determining a treatment regimen. For example, intracapsular joint disorders will be treated differently than musculoskeletal disorders. With virtually all TMJ disorders, however, numerous nonsurgical therapies are part of a treatment regimen ( Box 46-1 , Figure 46-1 ).

Splint therapy

Pharmacotherapy

Occlusal management

Physical therapy

Adjunctive therapies (acupuncture, acupressure, botulinum toxin A, etc.)

PHILOSOPHIES OF TREATMENT

The treatment of TMJ disorders involves philosophical differences among patients and practitioners. These differences often involve what one individual believes is the most appropriate course of treatment. Several treatment philosophies are universally accepted, including the use of a multidisciplinary approach, the use of reversible therapies first, and management of pain by alteration of the disease process.

MULTIDISCIPLINARY APPROACH

TMJ disorders, as discussed earlier, involve a variety of diagnoses. The disorders also influence multiple aspects of patients’ lives. For example, depression has been positively associated with TMJ complaints, especially painful symptoms. Because of this, a sole-practitioner approach to treating TMJ disorders is often inappropriate. A “team” approach is often necessary, using multiple specialties. Professionals from diverse disciplines, such as general dentistry, oral surgery, orthodontics, physical therapy, occupational therapy, psychiatry, and neurology, are often needed for thorough treatment.

REVERSIBLE VERSUS NONREVERSIBLE TREATMENT

A widely held philosophy is that the most appropriate disease therapy is the least invasive therapy that provides a positive outcome. A large reason for this is that the least invasive therapies are often reversible. Once the therapy is completed, the patient’s physiology is not significantly altered. Nonsurgical TMJ therapies often, but not always, fall into this category of reversible treatment. For example, long-term splint therapy can alter disk position and condylar morphology. After reversible therapies have been attempted and it has been determined that a disease process has not been adequately interrupted, nonreversible modalities should be initiated.

PAIN MANAGEMENT VERSUS DISEASE THERAPY

Most patient’s complaints of TMJ disorders involve pain. Clear delineation must be made within the therapy of TMJ disorders between palliative pain management and a therapy used to treat a disease process. Pain can be managed in multiple ways, but the most effective is with removal of the offending stimulus or disease process. During this process, however, medicinal pain management may be necessary. Patients must be educated in the nature of the disease process and what impact each treatment modality will have on that process.

SPLINT THERAPY

The use of occlusal splint therapy for the treatment of TMJ disorders dates back to Kingsley in 1877. Occlusal splints have, over the years, been advocated for the use of a variety of purposes. It follows that the design of the splints has been modified for each purpose. For example, Sved, Block, and Christensen used occlusal appliances to restore the vertical dimension of occlusion. In the 1940s, Thompson advocated mandibular repositioning using intraoral appliances. This form of treatment was postulated to “unload” the condyle. In the 1960s, Ramfjord popularized the use of splint therapy for patients with muscular dysfunction by using electromyographic studies. Further attempts were made to “unload” the condyle in the 1970s and 1980s with anterior repositioning appliances.

Splint therapy remains a popular method of treating TMJ disorders. Several studies have concluded that splint therapy is often an effective therapy, but the type of splint used seems to have little consequence. This is likely because the exact mechanism of action of splint therapy is not well understood. This section will highlight the different splints used and their specific uses ( Box 46-2 ).

Stabilization splints

Repositioning splints

Pivot splints

Soft splints

Bite plane splints

TYPES

- •

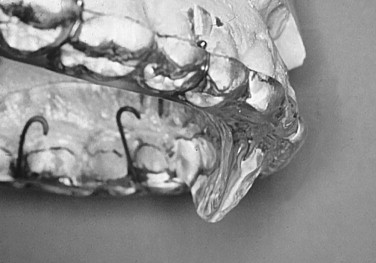

Stabilization splints: Stabilization splints are the most commonly used splints to treat myofascial pain ( Figure 46-2 ). They consist of acrylic full coverage of the maxillary or mandibular occlusal shelf. Most commonly, there is interdigitation with one arch, but little to no interdigitation with the other arch. Balanced, bilateral occlusal contacts are a must. If any interdigitation exists, anterior disclusion and canine guidance or group function is established. Stabilization splints are usually constructed in a centric relation. They have been shown to be moderately successful in reducing pain in longitudinal studies. Studies of full-coverage stabilization splints have been shown to have favorable results in symptoms related to joint, muscular, and motion pain, but demonstrate poor results at decreasing joint noise. Schmitter et al recently determined that patients treated with stabilization splints were treated more effectively than those with distraction splints. A recent Cochrane Database review of studies using stabilization splints concluded that there was insufficient evidence to support or discourage their use. This highlights the need for further well-controlled studies examining their efficacy.

FIGURE 46-2 Stabilization splint. - •

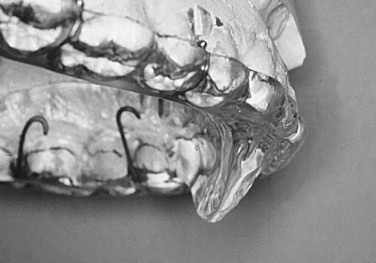

Repositioning splints: Repositioning splints are primarily used to alter the condylar position at occlusal contact and to recapture a displaced disk ( Figure 46-3 ). They are constructed out of hard acrylic for the maxillary or mandibular arch with cuspal interdigitation or inclines to guide the mandible to a predetermined position. Repositioning splints became popular in the early 1980s with promising results shown to decrease pain and joint noise in patients with anteriorly displaced disks with reduction. This initial enthusiasm, however, dwindled with controlled long-term studies showing a high rate of joint noise returning and progressive pain. Other studies have shown a significant improvement in pain, but marginal success in “recapturing” disks.

FIGURE 46-3 Maxillary anterior repositioning appliance worn unsupervised for 2 years. - •

Pivot splints: First described by Goodwillie in 1881, these splints are designed to “unload” the TMJ and to mildly stretch the joint ( Figure 46-4 ). They can be made for the mandibular or maxillary arch and made unilateral or bilateral depending on the involved joint(s). They were theorized to be useful in patients with intracapsular inflammation. Unfortunately, the elevator muscles of the mandible lie on or posterior to the most distal portion of the dentition. Without the use of a chin cup or other orthopedic device, unloading of the joint is difficult to achieve.

FIGURE 46-4 A pivot splint. Note that posterior acrylic blocks are thought to gently distract the condylar head when patient is in centric occlusion. - •

Soft splints: Soft, or resilient, splints are made from a pliable material and are often effective for immediate results in patients with myofascial pain ( Figure 46-5 ). They have an advantage of low cost and ease of fabrication. It is believed, however, that hard splints are superior to their soft counterparts, especially in cases of bruxism.

FIGURE 46-5 Soft splint. - •

Bite plane splints: Bite plane splints are used to disrupt mandibular proprioception, thereby decreasing muscle activity ( Figure 46-6 ). They are constructed by indexing only the anterior teeth with no posterior contact. Prolonged use can cause occlusal discrepancies ( Figure 46-7 ), and stabilization splints are more effective in bruxism cases.

FIGURE 46-6 Lateral view of maxillary anterior repositioning appliance. Note that resting of lower incisors is anterior to this flange.

FIGURE 46-7 Patient’s occlusion after 2 years of unsupervised wear. Note open posterior malocclusion.

USES

Myofascial Pain

Numerous studies have shown that splint therapy is effective for myofascial pain. Stabilization splints are the most common splints used. Other forms of splints have been advocated for myofascial pain with similar value; these are effective in 70% to 90% of cases. The exact reason why splint therapy is effective in myofascial pain is not yet determined. Numerous electromyography (EMG) studies have shown a short-term decrease in muscle activity, especially the temporalis and masseter muscles. Long-term EMG studies, however, have shown ambiguous results. This may be due to a traditionally cyclic nature of symptoms related to myofascial disorders.

A study by deLeeuw et al determined that patients with myofascial pain had a decrease in symptoms with splint usage compared with a control group. These patients were also shown to have a decrease in depression and an increase in the use of planned actions and rational thinking. It is not clear, however, if the reduction in symptoms caused a decrease in depression or if a decrease in depression caused a reduction in symptoms.

The effectiveness of splint therapy for myofascial pain has been brought into question by a study by Dao et al. In a parallel randomized controlled blinded study, patients were divided into three groups: brief splint usage only at recall appointments, palatal splint usage 24 hours a day (no occlusal coverage), and stabilization splint usage 24 hours a day. All three groups demonstrated a decrease in symptoms, with no statistically significant difference between the groups. The findings of this study support the theory of other authors who suggest that cognitive awareness and positive patient expectations may have an as large or larger role in treatment of TMJ disorders than the biomechanical impact of occlusal appliances.

The exact reason why splint therapy is effective for myofascial pain is yet to be determined. Further controlled studies are needed to validate any number of theories. The most effective type of splint used is also yet to be definitively determined. It is important, however, to use conservative and reversible appliances since some splints can have adverse effects on a patient’s occlusion.

Bruxism

Bruxism can cause several deleterious effects. First, bruxism can cause irreversible wear on the dentition. Second, bruxism can also cause moderate hypertrophy of the masticatory muscles, most notably the masseter. Third, bruxism can result in alteration of the TMJ anatomy over time. Lastly, the link between bruxism and myofascial pain is strong and quite possibly causative in many cases. Therefore if a patient with bruxism has a myofascial pain component, the same rationale for splint therapy applies.

EMG studies have shown a significant decrease in masseter and temporalis muscle activity with splint use in patients exhibiting nocturnal bruxism. These studies also show that the effect of splint therapy is not maintained once splint usage is halted. Muscle activity often returned to the pretreatment levels within several weeks after cessation of treatment. Further, a recent study by Raphael et al found pain to improve in patients with bruxism, but the splint therapy had little effect on the severity of the bruxism. This raises questions of the exact mechanism of splint therapy and if there is an exact causative nature of bruxism and myofascial pain.

Internal Derangement

Splint therapy has been used extensively for various intracapsular TMJ disorders with little definitive evidence indicating their therapeutic value. In attempting to treat anterior displaced disks with or without reduction, splints have been hypothesized to “recapture” a displaced disk into its natural position over the condylar head, especially during function. Cohen and MacAfee submitted that a proper meniscal-condylar position is essential to prevent future degenerative joint disease. This theory, however, has not been supported by further studies. Studies show that recapturing the disk with the use of splints is marginally effective in the short and long term. Furthermore, the use of repositioning splints can permanently alter the patient’s occlusion. The most effective use is in relation to pain symptoms, where likely the joint is “unloaded” leading to a decrease in inflammation. A decrease in inflammation may result in an increase in the range of motion.

In the case of anterior displaced disks with reduction, the theory is that a “joint unloading” will allow the disk to resume its natural position over the condylar head. Consistent repositioning of the disk has not been proven, but splint therapy has been shown to result in a decrease in joint loading. Nitzan et al studied the intraarticular pressure within the TMJ with and without an intraocclusal appliance. During clenching there was a decrease in intraarticular pressure of 81.2% with the occlusal appliance in place versus without it. Pivot splints have also been used for joint unloading and have shown that a fulcrum at the second molar area results in 1 to 3 mm of condylar lowering.

Similarly, splints have been used to treat anterior displaced disks without reduction. Their effectiveness, however, has been brought into question. A similar “joint unloading” phenomenon has been reported with a decrease in pain. It is theorized that over time the retrodiskal tissue becomes more fibrotic, with a decrease in vascularity and innervation. A study by Lundh et al, however, found no statistical benefit in pain or range of motion with the use of splints in patients with anterior disk displacement without reduction. Conversely a recent study by Ohnuki et al observed that pain symptoms improved with splint therapy with patients with anterior disk displacement without reduction. Posttreatment magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies, however, revealed that splint therapy had minimal effect on the disk’s position.

It is therefore reasonable to conclude that a definitive role of splint therapy in patients with internal derangement is yet to be determined. Splints do have a role in decreasing joint load, which may lead to an improvement in pain symptoms. Given the lack of a conclusive role, splint therapy, if chosen, should remain conservative and not cause irreversible changes to the occlusion or TMJ anatomy.

Degenerative Joint Disease

Degenerative joint disease includes osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis. Splint therapy has been shown to have a favorable therapeutic index to treat symptoms related to muscle activity and inflammation in the joint as a result of overload. If a patient is exhibiting pain in association with degenerative changes, splint therapy may be effective at treating the symptoms. Splint therapy, however, has not been shown to alter the course of degenerative joint disease.

SPLINT THERAPY

The use of occlusal splint therapy for the treatment of TMJ disorders dates back to Kingsley in 1877. Occlusal splints have, over the years, been advocated for the use of a variety of purposes. It follows that the design of the splints has been modified for each purpose. For example, Sved, Block, and Christensen used occlusal appliances to restore the vertical dimension of occlusion. In the 1940s, Thompson advocated mandibular repositioning using intraoral appliances. This form of treatment was postulated to “unload” the condyle. In the 1960s, Ramfjord popularized the use of splint therapy for patients with muscular dysfunction by using electromyographic studies. Further attempts were made to “unload” the condyle in the 1970s and 1980s with anterior repositioning appliances.

Splint therapy remains a popular method of treating TMJ disorders. Several studies have concluded that splint therapy is often an effective therapy, but the type of splint used seems to have little consequence. This is likely because the exact mechanism of action of splint therapy is not well understood. This section will highlight the different splints used and their specific uses ( Box 46-2 ).

Stabilization splints

Repositioning splints

Pivot splints

Soft splints

Bite plane splints

TYPES

- •

Stabilization splints: Stabilization splints are the most commonly used splints to treat myofascial pain ( Figure 46-2 ). They consist of acrylic full coverage of the maxillary or mandibular occlusal shelf. Most commonly, there is interdigitation with one arch, but little to no interdigitation with the other arch. Balanced, bilateral occlusal contacts are a must. If any interdigitation exists, anterior disclusion and canine guidance or group function is established. Stabilization splints are usually constructed in a centric relation. They have been shown to be moderately successful in reducing pain in longitudinal studies. Studies of full-coverage stabilization splints have been shown to have favorable results in symptoms related to joint, muscular, and motion pain, but demonstrate poor results at decreasing joint noise. Schmitter et al recently determined that patients treated with stabilization splints were treated more effectively than those with distraction splints. A recent Cochrane Database review of studies using stabilization splints concluded that there was insufficient evidence to support or discourage their use. This highlights the need for further well-controlled studies examining their efficacy.

FIGURE 46-2 Stabilization splint. - •

Repositioning splints: Repositioning splints are primarily used to alter the condylar position at occlusal contact and to recapture a displaced disk ( Figure 46-3 ). They are constructed out of hard acrylic for the maxillary or mandibular arch with cuspal interdigitation or inclines to guide the mandible to a predetermined position. Repositioning splints became popular in the early 1980s with promising results shown to decrease pain and joint noise in patients with anteriorly displaced disks with reduction. This initial enthusiasm, however, dwindled with controlled long-term studies showing a high rate of joint noise returning and progressive pain. Other studies have shown a significant improvement in pain, but marginal success in “recapturing” disks.

FIGURE 46-3 Maxillary anterior repositioning appliance worn unsupervised for 2 years. - •

Pivot splints: First described by Goodwillie in 1881, these splints are designed to “unload” the TMJ and to mildly stretch the joint ( Figure 46-4 ). They can be made for the mandibular or maxillary arch and made unilateral or bilateral depending on the involved joint(s). They were theorized to be useful in patients with intracapsular inflammation. Unfortunately, the elevator muscles of the mandible lie on or posterior to the most distal portion of the dentition. Without the use of a chin cup or other orthopedic device, unloading of the joint is difficult to achieve.

FIGURE 46-4 A pivot splint. Note that posterior acrylic blocks are thought to gently distract the condylar head when patient is in centric occlusion. - •

Soft splints: Soft, or resilient, splints are made from a pliable material and are often effective for immediate results in patients with myofascial pain ( Figure 46-5 ). They have an advantage of low cost and ease of fabrication. It is believed, however, that hard splints are superior to their soft counterparts, especially in cases of bruxism.

FIGURE 46-5 Soft splint. - •

Bite plane splints: Bite plane splints are used to disrupt mandibular proprioception, thereby decreasing muscle activity ( Figure 46-6 ). They are constructed by indexing only the anterior teeth with no posterior contact. Prolonged use can cause occlusal discrepancies ( Figure 46-7 ), and stabilization splints are more effective in bruxism cases.

FIGURE 46-6 Lateral view of maxillary anterior repositioning appliance. Note that resting of lower incisors is anterior to this flange.

FIGURE 46-7 Patient’s occlusion after 2 years of unsupervised wear. Note open posterior malocclusion.

USES

Myofascial Pain

Numerous studies have shown that splint therapy is effective for myofascial pain. Stabilization splints are the most common splints used. Other forms of splints have been advocated for myofascial pain with similar value; these are effective in 70% to 90% of cases. The exact reason why splint therapy is effective in myofascial pain is not yet determined. Numerous electromyography (EMG) studies have shown a short-term decrease in muscle activity, especially the temporalis and masseter muscles. Long-term EMG studies, however, have shown ambiguous results. This may be due to a traditionally cyclic nature of symptoms related to myofascial disorders.

A study by deLeeuw et al determined that patients with myofascial pain had a decrease in symptoms with splint usage compared with a control group. These patients were also shown to have a decrease in depression and an increase in the use of planned actions and rational thinking. It is not clear, however, if the reduction in symptoms caused a decrease in depression or if a decrease in depression caused a reduction in symptoms.

The effectiveness of splint therapy for myofascial pain has been brought into question by a study by Dao et al. In a parallel randomized controlled blinded study, patients were divided into three groups: brief splint usage only at recall appointments, palatal splint usage 24 hours a day (no occlusal coverage), and stabilization splint usage 24 hours a day. All three groups demonstrated a decrease in symptoms, with no statistically significant difference between the groups. The findings of this study support the theory of other authors who suggest that cognitive awareness and positive patient expectations may have an as large or larger role in treatment of TMJ disorders than the biomechanical impact of occlusal appliances.

The exact reason why splint therapy is effective for myofascial pain is yet to be determined. Further controlled studies are needed to validate any number of theories. The most effective type of splint used is also yet to be definitively determined. It is important, however, to use conservative and reversible appliances since some splints can have adverse effects on a patient’s occlusion.

Bruxism

Bruxism can cause several deleterious effects. First, bruxism can cause irreversible wear on the dentition. Second, bruxism can also cause moderate hypertrophy of the masticatory muscles, most notably the masseter. Third, bruxism can result in alteration of the TMJ anatomy over time. Lastly, the link between bruxism and myofascial pain is strong and quite possibly causative in many cases. Therefore if a patient with bruxism has a myofascial pain component, the same rationale for splint therapy applies.

EMG studies have shown a significant decrease in masseter and temporalis muscle activity with splint use in patients exhibiting nocturnal bruxism. These studies also show that the effect of splint therapy is not maintained once splint usage is halted. Muscle activity often returned to the pretreatment levels within several weeks after cessation of treatment. Further, a recent study by Raphael et al found pain to improve in patients with bruxism, but the splint therapy had little effect on the severity of the bruxism. This raises questions of the exact mechanism of splint therapy and if there is an exact causative nature of bruxism and myofascial pain.

Internal Derangement

Splint therapy has been used extensively for various intracapsular TMJ disorders with little definitive evidence indicating their therapeutic value. In attempting to treat anterior displaced disks with or without reduction, splints have been hypothesized to “recapture” a displaced disk into its natural position over the condylar head, especially during function. Cohen and MacAfee submitted that a proper meniscal-condylar position is essential to prevent future degenerative joint disease. This theory, however, has not been supported by further studies. Studies show that recapturing the disk with the use of splints is marginally effective in the short and long term. Furthermore, the use of repositioning splints can permanently alter the patient’s occlusion. The most effective use is in relation to pain symptoms, where likely the joint is “unloaded” leading to a decrease in inflammation. A decrease in inflammation may result in an increase in the range of motion.

In the case of anterior displaced disks with reduction, the theory is that a “joint unloading” will allow the disk to resume its natural position over the condylar head. Consistent repositioning of the disk has not been proven, but splint therapy has been shown to result in a decrease in joint loading. Nitzan et al studied the intraarticular pressure within the TMJ with and without an intraocclusal appliance. During clenching there was a decrease in intraarticular pressure of 81.2% with the occlusal appliance in place versus without it. Pivot splints have also been used for joint unloading and have shown that a fulcrum at the second molar area results in 1 to 3 mm of condylar lowering.

Similarly, splints have been used to treat anterior displaced disks without reduction. Their effectiveness, however, has been brought into question. A similar “joint unloading” phenomenon has been reported with a decrease in pain. It is theorized that over time the retrodiskal tissue becomes more fibrotic, with a decrease in vascularity and innervation. A study by Lundh et al, however, found no statistical benefit in pain or range of motion with the use of splints in patients with anterior disk displacement without reduction. Conversely a recent study by Ohnuki et al observed that pain symptoms improved with splint therapy with patients with anterior disk displacement without reduction. Posttreatment magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies, however, revealed that splint therapy had minimal effect on the disk’s position.

It is therefore reasonable to conclude that a definitive role of splint therapy in patients with internal derangement is yet to be determined. Splints do have a role in decreasing joint load, which may lead to an improvement in pain symptoms. Given the lack of a conclusive role, splint therapy, if chosen, should remain conservative and not cause irreversible changes to the occlusion or TMJ anatomy.

Degenerative Joint Disease

Degenerative joint disease includes osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis. Splint therapy has been shown to have a favorable therapeutic index to treat symptoms related to muscle activity and inflammation in the joint as a result of overload. If a patient is exhibiting pain in association with degenerative changes, splint therapy may be effective at treating the symptoms. Splint therapy, however, has not been shown to alter the course of degenerative joint disease.

PHARMACOTHERAPY

The treatment of TMJ disorders is often not effective with one modality alone. A complete treatment regimen involves multiple types of treatment reflective of the multifactorial nature of the disease process. Pharmacologic therapy quite often plays a central or adjunctive role in the treatment of TMJ disorders.

Pharmacologic therapy can be divided into two main categories: medications used to treat a certain disorder and medications used to palliate symptoms associated with the disorder. Several types of medication are used for both purposes. Imperative is a detailed discussion with the patient regarding the reason(s) why a certain medication is being prescribed and what is the desired end point. Continuing a medication, especially an analgesic, for an extended period of time is not a desirable method of treating TMJ disorders. Dependency, tolerance, or adverse side effects may occur. Furthermore, giving medications on an “as needed” basis should be avoided as much as possible. Instructions to take a medication “as needed” require the symptom to be present. This leads to an oscillating or cyclical process to the patient’s symptoms. More appropriate is to give medications on a schedule to prevent these variations in symptoms. The goal is to develop an individualized regimen that relieves the symptoms for a period of time, hopefully breaking the disease process and causing permanent improvement.

The categories of various pharmacologic treatment modalities are listed in Box 46-3 . The choice of one type of medication over another depends on the TMJ diagnosis and the severity of the patient’s symptoms. It is not uncommon to use medications from several categories to treat an individual’s disease process.

NSAIDs

Corticosteroids

Analgesics

Muscle relaxants

Antidepressants

Anxiolytics

NONSTEROIDAL ANTIINFLAMMATORY DRUGS (NSAIDs)

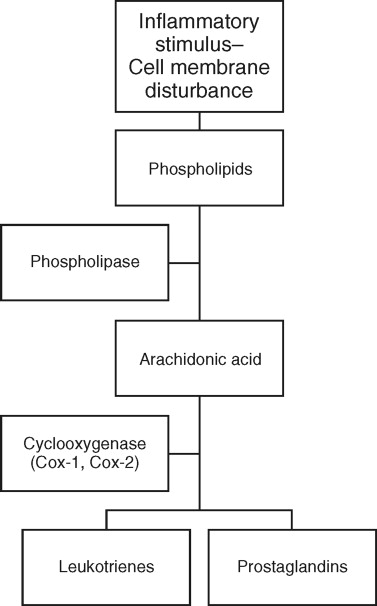

NSAIDs are used to treat TMJ disorders by two mechanisms: their analgesic effects and antiinflammatory properties. NSAIDs have been used in myofascial pain syndrome, synovitis, osteoarthritis, and symptomatic disk displacement. NSAIDs’ mechanism of action is to inhibit cyclooxygenase from converting arachidonic acid into prostaglandins and thromboxane. Arachidonic acid is released from cell membrane phospholipids in response to noxious stimuli. Prostaglandins promote multiple physiologic effects, including both inflammation and pain ( Figure 46-8 ).

NSAIDs act by temporarily preventing the binding of arachidonic acid to the cyclooxygenase enzyme. The exception to this is aspirin, where the cyclooxygenase enzyme is acetylated. Aspirin’s effects take longer to wear off because production of new cyclooxygenase molecules is needed to restore baseline function.

Two different cyclooxygenase enzymes (Cox-1 and Cox-2) produce prostaglandins. Cox-1 is a constitutive enzyme that is stimulated by normal physiologic processes and is always present. It affects platelet aggregation and renal blood flow, protects stomach mucosa, and regulates vasomotor tone. The Cox-2 enzyme is increased dramatically with the action of macrophages. This results in the formation of multiple prostaglandins that result in pain, increased swelling, and increased temperature.

All NSAIDs are active against Cox-1 and Cox-2, but the degree of effect that a particular NSAID has on either enzyme varies greatly. For example, aspirin is highly selective for Cox-1, whereas naproxen has a relatively equal effect on both enzymes. In general, the greater the effect that a particular NSAID has on Cox-1, the greater side effect profile it has. Most notably, this manifests as gastrointestinal irritation. It follows that NSAIDs should be chosen to maximize their Cox-2 effects and decrease their impact on Cox-1. This idea, though still believed, has been brought into question by recent reports of selective Cox-2 inhibitors causing various cardiovascular problems. Commonly prescribed NSAIDs are shown in Table 46-1 . Currently, ibuprofen and naproxen are the most prevalent, after usage of the selective Cox-2 inhibitors has decreased.

| Category | Generic Name | Brand Name | Usual Dosage | Relative Specificity Ratio of Cox-1 to Cox-2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Salicylates | Aspirin (acetylsalicylic acid) | Bayer | 650 mg q.i.d. (EC) | 166 |

| Diflunisal | Dolobid | 250 mg b.i.d. | ||

| Acetic acids | Indomethacin | Indocin | 25 mg t.i.d. | 60 |

| Sulindac | Clinoril | 150 mg b.i.d. | 100 | |

| Diclofenac | Voltaren | 50 mg t.i.d. | −1.4 | |

| Propionic acids | Ibuprofen | Motrin, Advil | 600 mg t.i.d | 15 |

| Naproxen | Naprosyn | 375 mg b.i.d. | −1.7 | |

| Ketoprofen | Orudis | 50 mg t.i.d | ||

| Flurbiprofen | Ansaid | 100 mg b.i.d. | 1.2 | |

| Fenamic acids | Meclofenamate | Meclomen | 50 mg q.i.d. | 7 |

| Mefenamic acid | Ponstel | 250 mg q.i.d. | ||

| Oxicams | Piroxicam | Feldene | 20 mg q.o.d. | 250 |

| Meloxicam | Mobicox | 7.5 mg q.o.d. | −3.0 | |

| Pyranocarboxylic acids | Etodolac | Ultradol | 300 mg b.i.d. | 0.1 |

| Naphthylalkanones | Nabumetone | Relafen | 1 g q.o.d. | |

| Cox-2 inhibitors | Celecoxib | Celebrex | 200 mg q.o.d. | 0.003 |

| Rofecoxib | Vioxx | 25 mg q.o.d. | 0.026 | |

| Valdecoxib | Bextra | 20 mg q.o.d. |

CORTICOSTEROIDS

Various corticosteroids used in TMJ disorders are shown in Table 46-2 . Corticosteroids interrupt the inflammatory cascade by completely blocking the formation of arachidonic acid by blocking phospholipase ( Figure 46-8 ). This results in a greater effect on the formation of prostaglandins than that found with NSAIDs. Their effect on acute TMJ pain and hypomobility is therefore greater than that found with NSAIDs. Long-term use of corticosteroids for the treatment of TMJ disorders, however, is contraindicated. It has been shown that usage of prednisone more than 10 to 20 mg a day for 2 weeks can cause suppression of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis. This can result in a Cushing’s-like disease process, acute adrenal crisis, hypotension, electrolyte abnormalities, and diabetes. Chronic steroid administration can also result in the formation of osteoporosis including the TMJ. This is because the mandibular condyle has a reduced ability to withstand stress and may go through destructive changes.

| Drug | Alternative Name | Relative Potency | Usual Dose |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrocortisone | Hydrocortone | 1 | 20-240 mg/day |

| Prednisone | Deltasone, Orasone | 4 | 5-60 mg/day |

| Prednisolone | Delta-Cortef | 4 | 5-60 mg/day |

| Dexamethasone | Decadron | 25 | 0.75-9.0 mg/day |

| Betamethasone | Celestone | 25 | 0.6-7.2 mg/day |

The use of intracapsular corticosteroid injections is discussed elsewhere in this text. The use of oral corticosteroids should be reserved for significant acute TMJ discomfort or for diagnostic purposes. The course of drug administration should be short and repeated as infrequently as possible. A typical regimen is a tapering dose lasting 5 to 7 days.

ANALGESICS

Practitioners have a wide array of opinions regarding the role of analgesics in TMJ disorders. Prescribed duration and dosage vary significantly. Patients’ attitudes toward analgesics are also variable. Patients must be aware that the use of analgesic medications likely will not “cure” their TMJ disorder. It is permissible for patients to use analgesics for symptomatic relief, but they must be aware that by taking the medication the disease process is not halted.

The use of analgesics in TMJ disorders can be divided into two main categories: narcotic and nonnarcotic analgesics. The primary nonnarcotic medications used are the NSAIDs, which were discussed previously. Acetaminophen is another commonly used nonnarcotic analgesic. Acetaminophen does have some antiinflammatory properties, but is mainly used for pain relief. High dose or long-term usage of acetaminophen can cause liver dysfunction. It is contraindicated in patients with liver disease or moderate alcohol consumption.

Opioid analgesics are a class of phenanthrene alkaloids with a first known use in sixteenth century Egypt. Multiple opioid receptors have been discovered over the years, but the mu receptor has been found to be the principle receptor involved in analgesia. Opioid analgesics act at sites in the brainstem for descending pain inhibition, elsewhere in the brain raising the threshold to a painful stimulus, or peripherally in peripheral nociceptors. Opioid analgesics have adverse effects, including decreased gastrointestinal motility, respiratory depression, urine retention, sedation, and nausea and vomiting.

A large drawback to the use of opioids is a potential tolerance to the medication with chronic usage. Physical and psychological dependence on opioids is possible with repeated administration. Commonly used opioid analgesics are shown in Table 46-3

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses