This article describes the combined use of maxillary expansion and a protraction facemask in the correction of a skeletal Class III malocclusion after the patient’s pubertal growth spurt. Treatment efficacy and the effects on facial and smile esthetics are presented. The nonextraction option with an arch-size increase and stability issues is discussed.

Highlights

- •

A maxillary protraction facemask was effective after the patient’s peak of pubertal growth spurt.

- •

Midpalatal suture opening with rapid maxillary expansion enhanced the orthopedic effect of the facemask and vice versa.

- •

Combined rapid maxillary expansion and facemask effects optimized anterior tooth display and reduction of lateral negative spaces.

- •

Individual dentofacial characteristics may allow clinicians to push the envelope of treatment beyond central tendencies.

Treatment of Class III malocclusions in growing children is a clinical challenge for the orthodontist. Growth is unpredictable and often unfavorable with this skeletal pattern. Because of our limited ability to influence mandibular growth and the possibility of separating maxillary sutural attachments, treatment has shifted to the maxillary protraction paradigm. Moreover, maxillary retrusion was found to be the most contributory factor to a skeletal Class III malocclusion. The well-documented literature on greater orthopedic effects in younger children has discouraged clinicians from using facemasks after 10 years of age. This case report illustrates the long-term positive response to late facemask therapy and the stability of nonextraction treatment with increases in the arch perimeters.

Diagnosis and etiology

The patient was a girl, age 12 years 9 months, whose chief complaint was an unpleasant smile and crowded teeth. Her medical history was noncontributory. Her dental history included routine dental evaluations and restorations on the maxillary central incisors, first molars, and left first premolar. There were carious lesions on the mesial aspects of the maxillary lateral incisors and white decalcification spots at the upper third of the central incisors. Her oral hygiene was poor, and she had gingival inflammation. The probable cause of her malocclusion was a combination of genetic and developmental factors.

The patient had a straight profile with a tendency to upper and lower lip retrusion. The nasolabial angle was increased, and the throat length normal. From a frontal view, the face was symmetrical and well balanced. Mild paranasal hollowing was noticed. The lips were competent at rest, and the upper lip vermilion was thin. She had a low lip line upon smiling, displaying half the clinical crown height of the maxillary incisors along with the mandibular teeth. The smile arc was nonconsonant, with flat maxillary incisal edges not running along the lower lip curvature ( Fig 1 ).

Intraorally, she had an Angle Class I molar relationship and an anterior edge-to-edge bite. There was anterior crowding, with the maxillary lateral incisors blocked in, and the maxillary and mandibular canines blocked out. The mandibular left canine had a thin band of attached gingiva. The arch-length deficiencies were 10.5 mm in the maxillary arch and 6.5 mm in the mandibular arch. The transpalatal arch width at the first molars was 31.1 mm, which was smaller than the average normal width of 35.4 mm. The maxillary left first premolar and first molar were in crossbite. The maxillary dental midline was deviated slightly to the patient’s right in relation to the facial midline, whereas the mandibular midline was deviated to the left, leading to a 3-mm dental midline discrepancy ( Figs 1 and 2 ).

The panoramic radiograph showed a full complement of teeth, including developing third molars. The overall bone level was within normal limits ( Fig 3 ).

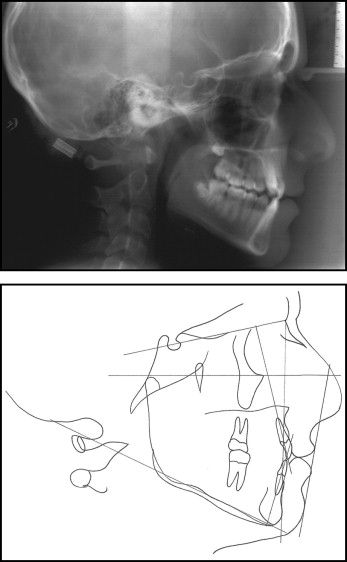

The cephalometric analysis showed a skeletal Class III anteroposterior relationship evidenced by an ANB angle of 0° and a Wits appraisal of −6 mm. The maxillary and mandibular incisors were upright, and the soft-tissue analysis confirmed lip retrusion with an increased value of the Holdaway line to the tip of the nose ( Fig 4 , Table I ). The skeletal age as assessed from the lateral cephalometric radiograph was 12 years 8 months. This was evaluated according to the method of Hassel and Farman, combining the observations of the hand-wrist changes (Fishman method ) and the changes in the cervical vertebrae during skeletal maturation.

| Measurement | Norm | Before treatment | After treatment | 5 years posttreatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Skeletal | ||||

| SNA (°) | 82 | 77 | 77 | 78 |

| SNB (°) | 80 | 77 | 77 | 77 |

| ANB (°) | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| FH-NA (max depth) (°) | 90 | 89 | 89 | 90 |

| FH-NP (facial angle) (°) | 87 | 89 | 89 | 90 |

| Wits (mm) | 1 | −6 | −1 | −3 |

| SN-MPA (°) | 32 | 38 | 37 | 38 |

| FMA (°) | 25 | 26 | 26 | 26 |

| Dental | ||||

| U1-SN (°) | 103 | 91 | 111 | 109 |

| U1-NA (°) | 22 | 15 | 34 | 31 |

| U1-NA (mm) | 4 | 2 | 10 | 10 |

| L1-NB (°) | 25 | 15 | 28 | 25 |

| L1-NB (mm) | 4 | 2 | 8 | 8 |

| L1-MP (°) | 87 | 80 | 94 | 90 |

| L1-APo (mm) | 1 | 2 | 8 | 8 |

| U1-L1 (°) | 131 | 150 | 113 | 124 |

| Soft tissue | ||||

| Facial contour angle (°) | 11 | 10 | 14 | 15 |

| Holdaway line (mm) | ||||

| Tip of nose | 9 | 11 | 10 | 10 |

| Subnasale | 5 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| Upper lip | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Lower lip | 0 | 0 | −1 | −1 |

| Supramentale | 5 | 4 | 4 | 3 |

| Pogonion | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Treatment objectives

The main objective in treating this malocclusion was to improve the smile, which was the patient’s chief complaint. The crowding and arch-length deficiency needed to be corrected and the uprighted maxillary and mandibular incisors proclined to improve lip support. The skeletal Class III anteroposterior relationship also had to be addressed to help correct the anterior edge-to-edge bite and enhance the facial profile and smile esthetics. Addressing the transverse maxillary arch deficiency would help achieve an optimal posterior intercuspation.

Treatment objectives

The main objective in treating this malocclusion was to improve the smile, which was the patient’s chief complaint. The crowding and arch-length deficiency needed to be corrected and the uprighted maxillary and mandibular incisors proclined to improve lip support. The skeletal Class III anteroposterior relationship also had to be addressed to help correct the anterior edge-to-edge bite and enhance the facial profile and smile esthetics. Addressing the transverse maxillary arch deficiency would help achieve an optimal posterior intercuspation.

Treatment alternatives

Three treatment options were considered.

- 1.

Extraction of 4 first premolars to reposition the blocked-out canines. The 2 main advantages of this treatment option are the efficiency to resolve the severe arch-length deficiency and the possible long-term stability of tooth alignment. Nevertheless, a 4-premolar extraction treatment would not address the upright incisors and the lip retrusion, and might even worsen the profile.

- 2.

Extraction of the maxillary first premolars. This would address the arch-length deficiency that was more severe in the maxillary arch, with a less adverse effect on the profile than would extraction of 4 premolars. Class III elastics would help correct the anterior edge bite and finish in a Class II molar relationship. However, the facial and smile esthetics would not be optimized.

- 3.

Nonextraction with rapid maxillary expansion (RME) and maxillary protraction facemask treatment. The arch-length deficiency would be resolved by transverse and anteroposterior arch expansion. The combined orthopedic effects of RME and the facemask would bring the maxilla downward and forward. This would enhance both the profile and the smile esthetics by increasing incisor display. However, this treatment plan relies on patient cooperation and might have questionable long-term stability.

The nonextraction, RME, and facemask treatment option was adopted because it would optimize facial and smile esthetics. Cooperation and stability issues were discussed with the patient and her parents.

Treatment progress

A tissue-borne appliance with bands attached to the first premolars and first molars was used for RME. The appliance was activated by turning the screw once a day for 30 days, resulting in approximately 7 mm of arch widening at the level of the first molars ( Fig 5 ). Central incisor separation and an occlusal radiograph confirmed the midpalatal suture opening ( Fig 6 ). The screw was then locked with a double ligature tie, and the facemask was initiated. The elastics were hooked from the first premolar brackets on the RME to the horizontal outer bow of the facemask in a 30° downward and forward direction, delivering 450 g of force per side for 12 to 14 hours per day ( Fig 7 , A ). The facemask was worn for a total of 15 months. The RME was kept for 7 months as a stabilizer and replaced by an intraoral splint attached to the first molar bands with a palatal wire and a labial wire with soldered elastic hooks ( Fig 7 , B and C ). The mandibular arch was bonded with edgewise brackets (0.022 × 0.028 in) 11 months after RME was initiated, and the maxillary arch was bonded 5 months later when the facemask was discontinued. A normal progression of archwires, starting with 0.014-in nickel-titanium alloy and working up to 0.018-in stainless steel, was used to level, align, and coordinate the arches. Interarch posterior and anterior elastics were also needed to achieve proper occlusal interdigitation. Her cooperation was excellent, and the appliances were removed at age 16 years 8 months, 3 years after the start of fixed appliance treatment.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses