Introduction

For over 50 years, the American Heart Association has made recommendations for the prevention of infective endocarditis. The first guidelines were published in 1955; since then, they have been updated 9 times, most recently in 2007. There is still confusion about which orthodontic procedures are most prone to generate bacteremias and lead to infective endocarditis in susceptible patients. The aim of this study was to conduct a survey to determine orthodontists’ knowledge, attitudes, and in-office behaviors regarding the American Heart Association’s guidelines.

Methods

A 4-page online survey consisting of 3 sections was sent to members of the American Association of Orthodontists by using a random number generator. The first section consisted of demographic information, the second consisted of questions about the respondents’ practice characteristics, and the third included questions about the respondents’ knowledge and management of the treatment of patients at risk for infective endocarditis. There were 78 responses.

Results and Conclusions

Orthodontists are screening for cardiac problems in the patient’s medical history but to a lesser extent are requesting written medical clearance from the patient’s physician before starting orthodontic treatment. Many of the orthodontists surveyed believed that their knowledge of the American Heart Association’s guidelines and management of high-risk patients was in the good-to-excellent range. Orthodontists recommend antibiotic prophylaxis most frequently during band placement and removal. Patients at risk for infective endocarditis are somewhat likely to inquire about possible treatment sequelae associated with previous cardiac problems.

For over 50 years, the American Heart Association has made recommendations for the prevention of infective endocarditis. The first guidelines were published in 1955 and, since then, have been updated 9 times, most recently in 2007. Infective endocarditis is a rare disease that can be life threatening. Despite advances in medicine, morbidity and mortality can result. Although the incidence of endocarditis is hard to measure, most cases are not attributable to invasive dental procedures. It is difficult to conduct controlled trials to positively establish that antibiotic prophylaxis provides protection against endocarditis during invasive procedures. Also, there is still confusion about which orthodontic procedures might generate bacteremias, which can lead to infective endocarditis in susceptible patients.

The relationship between orthodontics and infective endocarditis has not been fully defined. Although controversial, it is widely assumed that there are correlations among poor oral hygiene, the severity of periodontal disease, the type of dental procedure, and the frequency, nature, magnitude, and duration of bacteremia. However, evidence supports that good oral hygiene with no dental disease will decrease the frequency of bacteremia resulting from daily activities. Most recent studies have focused on which dental procedures seemed to cause the greatest risk of endocarditis. As shown in Table I , dental extractions have been reported in the past to have the highest incidence of bacteremia, ranging from 10% to 100%. However, other studies have shown that other dental procedures such as periodontal surgery, scaling and root planning, dental prophylaxis, rubber dam matrix wedge placement, and endodontic procedures pose risks for bacteremia similar to those of tooth extractions.

| Procedure | Incidence of bacteremia |

|---|---|

| Extraction | 10%-100% |

| Periodontal surgery | 36%-88% |

| Periodontal scaling | 8%-80% |

| Dental prophylaxis | 0%-40% |

| Endodontic therapy (manipulation within apex) | 0%-20% |

| Tooth brushing | 0%-40% |

| Irrigating devices | 7%-50% |

| Tooth picks | 20%-40% |

| Chewing | 17%-51% |

| Periodontal disease (patient resting) | 11% |

| Periodontal disease (resting but anaerobic technique) | 60%-80% |

Biancaniello and Romero reported 2 cases in which each child with a history of congenital cardiac defects developed endocarditis within 6 months after adjustment of their orthodontic appliances. Hobson and Clark reported in a case study that a patient developed endocarditis within 2 weeks after archwire adjustments. In both articles, however, there was no conclusive evidence linking orthodontic treatment to causing infective endocarditis, and the relationship might have been coincidental. In 1995, Hobson and Clark also surveyed 1038 orthodontists and found only 8 cases of infective endocarditis diagnosed during or after orthodontic treatment. They concluded that the risk for infective endocarditis was minimal. McLaughlin et al found bacteremia in 10% of blood samples during band placement. On the other hand, Degling found no bacteremia during banding in that study. The American Heart Association’s committee concluded that adjustment of orthodontic appliances does not pose a significant risk for bacteremia. Hence, the guidelines do not recommend prophylaxis for routine adjustment of fixed and removable orthodontic appliances.

No current published data have shown which dental procedures can cause greater frequencies of bacteremia, compared with routine daily activities such as mastication, tooth brushing, or flossing. Previous American Heart Association guidelines based the criteria for antibiotic prophylaxis on whether bleeding occurred during a dental procedure. For procedures in which bleeding was expected, prophylaxis was recommended. However, research does not support the claim that bleeding is a reliable indicator for infective endocarditis. As a result, this led the previous American Heart Association guidelines to suggest antibiotic prophylaxis for some procedures and not for others.

Previous studies have been controversial on whether antibiotics can prevent or reduce the frequency, magnitude, or duration of bacteremia from dental procedures. Lockhart et al reported that antibiotics have been statistically successful in reducing the frequency, nature, or duration of bacteremias from dental procedures, whereas the report by Roberts counters that conclusion. However, the results of the study of Lockhart et al do not indicate that bacteremia was eliminated altogether. Conversely, Hall et al reported that neither penicillin V nor amoxicillin therapy was effective in reducing the frequency of bacteremia compared with untreated control subjects. In another study, Hall et al found that patients treated with penicillin or ampicillin after dental extractions compared with placebos did have a lower percentage of viridans group streptococci and anaerobes in culture. Ten minutes after the extractions, however, there was no significant difference. No data have shown that a reduction in bacteremia from amoxicillin lowered the risk of infective endocarditis.

Previous American Heart Association guidelines categorized the underlying cardiac conditions in the low, moderate, and high risk categories. These categories were then used to recommend antibiotic prophylaxis for patients in the high and moderate risk categories. The American Heart Association gave several reasons for revising the guidelines. The current guidelines no longer recommend prophylaxis based solely on an increased lifetime risk of acquiring infective endocarditis because it is believed that only a few cases of infective endocarditis can be prevented by antibiotic prophylaxis, even if prophylaxis is 100% effective. It identified patients with underlying conditions, including a prosthetic cardiac valve or a previous episode of infective endocarditis, and some patients with congenital heart disease, as among those with the highest lifetime risk of acquiring bacteremia. As a result of the revisions, fewer patients will be receiving antibiotic prophylaxis.

In a major departure from the former guidelines, which listed certain dental procedures for which antibiotic prophylaxis was recommended, the current guidelines now recommend prophylaxis on any “dental procedures that involve manipulation of gingival tissues or the periapical region of the teeth or perforation of the oral mucosa.” These procedures include placement and removal of orthodontic bands but do not include routine anesthetic injections through noninfected tissues, dental radiographs, placement of removable prosthetic or orthodontic appliances, adjustment of orthodontic appliances, placement of orthodontic brackets, shedding of deciduous teeth, and bleeding from trauma to lips or oral mucosa. This, of course, also includes the placement of temporary anchorage devices. The antibiotic prophylaxis regimen remains unchanged since 1997. It recommends that antibiotic prophylaxis should be administered in a single dose before the procedure. If antibiotics were not administered before the procedure, prophylaxis can still be given up to 2 hours afterward.

The aim of this study was to conduct a survey to determine orthodontists’ knowledge, attitudes, and in-office behaviors regarding the American Heart Association’s guidelines for the prevention of infective endocarditis.

Material and methods

To examine orthodontists’ knowledge and management of the most recently published American Heart Association guidelines, a 4-page online questionnaire was drafted. Our subjects consisted of members of the American Association of Orthodontists. The respondents’ e-mail addresses were generated from the American Association of Orthodontists’ membership directory by using a random number generator. All respondents practiced in the United States, and all had to report their primary activity as the practice of orthodontics to be eligible for the study. Three hundred and four surveys were distributed by e-mail to obtain a sample size of 78 respondents, resulting in a response rate of 26.5%. Two additional reminder e-mails were sent 10 days apart to follow up. An introductory letter was attached to each e-mail message describing the details of the survey and asking for participation in the study. The letter briefly described the study, emphasized its purpose and research goals, and the importance of the respondent’s participation, and ensured confidentiality.

The questionnaire consisted of 3 sections, totaling 29 questions, and was formatted on Survey Monkey. The first section consisted of questions about the respondent’s characteristics. The second section consisted of the respondent’s practice characteristics and history-taking practices. The last section of the questionnaire included questions about knowledge and management of patients at risk for infective endocarditis. All completed questionnaires were assigned an identification number. All responses were entered into a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet (2007; Redmond, Wash). Any comments were also entered into the spreadsheet. All information was transferred to SPSS software (version 17; SPSS, Chicago, Ill). Frequencies and means were calculated for all data. Bivariate correlations, comparisons of means, and paired t tests were also used.

Results

The profiles of the respondents in our study and the national reported averages are presented in Table II . The sex ratio in this study was different from those in national reports. The average number of years in practice in our study was 14 years. The rest of the sample profile attributes were similar to national averages.

| Our study | National reports | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | Men, 47%; women, 53% | Men, 85%; women, 15% |

| Average years out of residency | 14 years | 15 years |

| Median age group | 40-49 years | 52 years |

| Average years in practice | 14 years | 21 years |

| Average hrs/wk spent in direct patient care | 30 hours | 31 hours |

| Average patients treated on a typical day | 55 patients | 54 patients |

| Average percentage of adults in practice | 22% | 20% |

The respondents were asked to rate their knowledge of the guidelines published by the American Heart Association for the prevention of infective endocarditis and managing orthodontic treatment for patients at high risk for endocarditis. Practitioners rated their knowledge with the categories of limited, moderate, good, or excellent. When they were asked to self-assess their knowledge of the American Heart Association’s guidelines for the prevention of infective endocarditis, 63.0% responded good, and 16.4% responded excellent. When they were asked to self-assess their knowledge of managing orthodontic treatment for patients at risk for endocarditis, 57.5% responded good, and 17.8% responded excellent.

In comparison, the respondents were then objectively examined on their knowledge of the risk assessment aspects of the guidelines. Four cardiac conditions (prosthetic cardiac valves, physiologic heart murmurs, myocardial infarct in the last 6 months, and previous episode of infective endocarditis) were presented, and the practitioners were asked whether they regarded patients with these conditions as having a low, moderate, or high risk for infective endocarditis. The results are shown in Table III . For prosthetic cardiac valves, 59.0% responded with high risk. For physiologic heart murmurs, 70.5% responded with low risk. For myocardial infarct in the last 6 months, 35.6% responded with moderate risk. For previous infective endocarditis, 73.1% responded with high risk.

| Cardiac conditions (n = 78) | Low risk | Moderate risk | High risk |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prosthetic cardiac valves | 10.3% (n = 8) | 30.8% (n = 24) | 59.0% (n = 46) correct |

| Physiologic heart murmurs | 70.5% (n = 55) correct |

26.9% (n = 21) | 2.6% (n = 2) |

| Myocardial infarct in the last 6 months | 25.6% (n = 20) | 35.6% (n = 27) correct |

37.0% (n = 31) |

| Previous infective endocarditis | 9.0% (n = 7) | 17.9% (n = 14) | 73.1% (n = 57) correct |

Virtually all respondents (97.4%) reported that they obtain and review a patient’s medical information, which includes questions about cardiac conditions, as part of their medical history. However, only 57.7% of the respondents required medical clearance for patients with a positive history of heart problems. When the respondents were asked to estimate the number of patients they have referred for evaluation of suspected endocarditis, only 7 orthodontists (13.7%) stated that they made referrals in the past year.

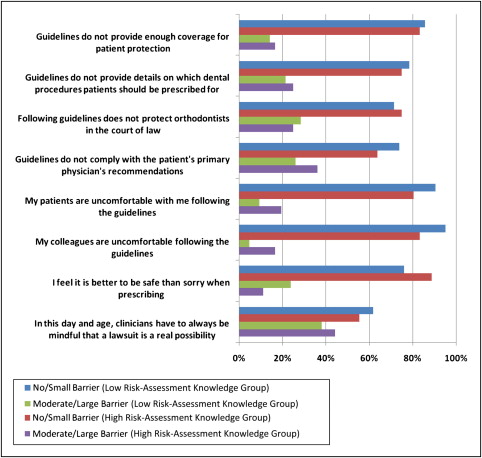

Relatively few orthodontists communicated with the patient’s primary physician. Of those who require a medical clearance from patients with a history of heart problems, 69.8% responded seldom or never, and 30.2% responded sometimes or often, to how often they communicate with the patient’s physician. The last parameter examined, in terms of the orthodontists’ management of infective endocarditis, was the extent to which respondents viewed aspects of the American Heart Association’s guidelines as barriers toward implementing them in their private practice. The Figure details the respondents’ perceptions of several barriers and whether they regard them as no-to-small barriers or moderate-to-large barriers.