“Massive compound facial injuries creates a sense of dismay which may lead to therapeutic inertia” — M.D. Moore

Managing avulsive facial injuries can be a very daunting task, even to the most seasoned surgeon. The initial appearance of these patients, in fact, can lead to a “therapeutic inertia” as stated by Moore. The goal of this chapter is to aid the treating surgeon and to familiarize the surgeon in training with the management goals, sequence, and surgical options available to reconstruct these patients, in order to restore function and improve aesthetics. The surgeon faced with the task of reconstructing patients with large avulsive tissue loss of the face needs to have an understanding of wound management, particularly wounds resulting from gunshot injuries. The surgeon will also need to have from the outset a very candid discussion with the patient and the family as to the task at hand and the number of surgical procedures the patient will likely require. One of the less commonly understood and appreciated aspects of the care of these patients is the psychological component and the psychosocial implications of these devastating injuries. Most surgeons who are routinely involved in the management of facial trauma patients have had the experience in which loved ones show the surgeon the best preinjury photos of the patient with the request that the patient be restored to his or her preinjury appearance. However, a realization of the limitation of the surgical intervention has to be understood by both the patient and their family as well as the surgical team. This important point has to be brought to light during the early phases of treatment so that realistic goals and expectations can be set.

WOUND ASSESSMENT

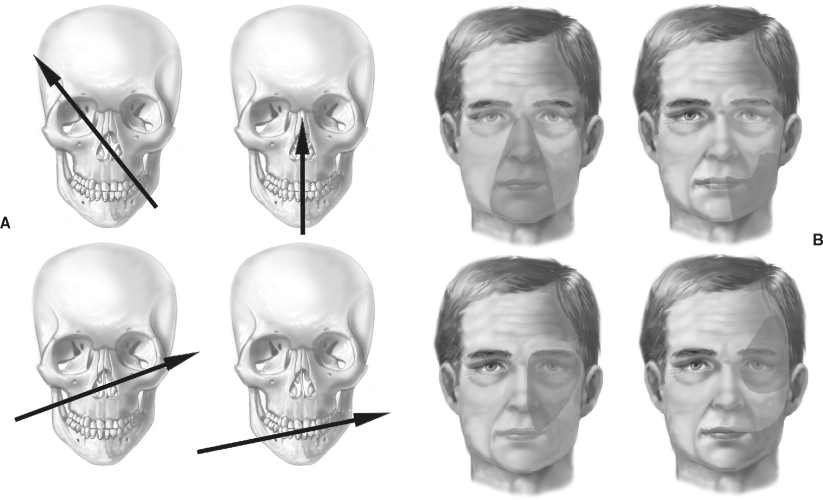

The most common reason for large avulsive facial tissue defects at most level I trauma centers is gunshot injuries. Clark and colleagues are credited with the most frequently used classification pattern for gunshot injuries to the facial skeleton. They defined the following four patterns: the frontal cranium, the orbit, the lower midface, and the mandible. The resulting tissue damage from these patterns forms the zones of injuries. The zones are the central face, the lateral mandible, the lateral midface and orbit, and the lateral cranium and orbit ( Figure 19-1 ). An understanding of ballistics is important because it helps the surgeon in assessing and understanding the wound beyond what is clinically apparent. Initially, the bullet crushes sufficient tissue to make a hole (entrance) through which it penetrates the underlying tissue (permanent cavity). Depending upon the speed at which the bullet is traveling and the bullet’s caliber, the walls of the permanent cavity radiate outward to form a temporary cavity. Understanding this basic principle is paramount to determining the initial management of the wound.

MANAGEMENT

INITIAL ENCOUNTER

Airway

The initial assessment of patients with significant facial injuries should always center on assessing and securing the airway. Patients who have suffered significant facial avulsive tissue loss will often present with significant bleeding, and often debris in the airway. At the time of initial presentation in the trauma bay, these patients will often have a secured airway that was obtained in the field. In instances in which this has not occurred because of the complexity of the case, bleeding, and/or obscurement of the airway secondary to debris, the airway has to be secured. The potential for cervical spine injuries must always be considered, and as such the neck should not be manipulated while securing the airway. If the conventional oral airway is not possible, a surgical airway should be obtained. The first and only airway that should be attempted in this situation is the cricothyroidotomy. This airway is simple and easy to obtain while requiring minimal dissection and limiting the potential for bleeding as with a tracheotomy. The cricothyroidotomy can later be converted to a tracheotomy in the operating room setting.

Clinical Examination

Once the airway is secured, attention is diverted to the management of bleeding and other life- or limb-threatening conditions. Once the primary survey is completed, the maxillofacial specialist can then systematically and methodically assess the extent of the injuries, evaluating all of the injured structures as well as any missing tissues. Particular attention is taken to assess nerve injuries and injuries to special structures such as the globe, salivary duct, and lacrimal duct. The assessment of the extent of hard tissue injury and loss is evaluated first clinically and then by diagnostic imaging.

Imaging

Imaging of the maxillofacial region continues to improve with each passing day. Gone are the days of relying solely on plain radiographic images to ascertain the extent of injuries. Today the vast majority of patients presenting to the emergency department with facial injuries will have a computed tomography (CT) scan. The technological improvements in CT scanning now enable the clinician to immediately obtain very complex three-dimensional renderings of the facial skeleton that will aid in planning the surgical intervention.

Integration of three-dimensional scanning with CT angiography allows for the visualization of the regional vasculature, which can be assessed for injury or for potential sites of anastomosis in microvascular repair of the missing structures.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Debridement

The conventional wisdom in management of gunshot wounds (GSWs) and other severe facial injuries with extensive tissue maceration is surgical debridement. After the initial encounter and airway management and hemorrhage control, a very conservative surgical debridement is carried out. This initial debridement is performed on only obviously unsalvageable tissues. At the conclusion of the first debridement, an attempt at soft tissue closure is carried out. This is done to obtain tenting of the soft tissue over the exposed bony skeleton and to prevent soft tissue contractures. The patient is transported to the operating room every other day for further conservative debridement, and initial stabilization of the facial fractures. While the surgeon is providing this initial therapy, he/she should be assessing the extent of missing tissue, both hard and soft, and the surgical options available to reconstruct the defect. The reconstructive surgeon should always be planning potential local, regional, and/or distant flaps. This awareness will prevent the unwanted sacrifice of blood vessels that supply potential flaps or possible recipient vessels for later microvascular anastomosis. The end point for the debridement is the establishment of a healthy tissue bed for the eventual final reconstruction.

MANAGEMENT

INITIAL ENCOUNTER

Airway

The initial assessment of patients with significant facial injuries should always center on assessing and securing the airway. Patients who have suffered significant facial avulsive tissue loss will often present with significant bleeding, and often debris in the airway. At the time of initial presentation in the trauma bay, these patients will often have a secured airway that was obtained in the field. In instances in which this has not occurred because of the complexity of the case, bleeding, and/or obscurement of the airway secondary to debris, the airway has to be secured. The potential for cervical spine injuries must always be considered, and as such the neck should not be manipulated while securing the airway. If the conventional oral airway is not possible, a surgical airway should be obtained. The first and only airway that should be attempted in this situation is the cricothyroidotomy. This airway is simple and easy to obtain while requiring minimal dissection and limiting the potential for bleeding as with a tracheotomy. The cricothyroidotomy can later be converted to a tracheotomy in the operating room setting.

Clinical Examination

Once the airway is secured, attention is diverted to the management of bleeding and other life- or limb-threatening conditions. Once the primary survey is completed, the maxillofacial specialist can then systematically and methodically assess the extent of the injuries, evaluating all of the injured structures as well as any missing tissues. Particular attention is taken to assess nerve injuries and injuries to special structures such as the globe, salivary duct, and lacrimal duct. The assessment of the extent of hard tissue injury and loss is evaluated first clinically and then by diagnostic imaging.

Imaging

Imaging of the maxillofacial region continues to improve with each passing day. Gone are the days of relying solely on plain radiographic images to ascertain the extent of injuries. Today the vast majority of patients presenting to the emergency department with facial injuries will have a computed tomography (CT) scan. The technological improvements in CT scanning now enable the clinician to immediately obtain very complex three-dimensional renderings of the facial skeleton that will aid in planning the surgical intervention.

Integration of three-dimensional scanning with CT angiography allows for the visualization of the regional vasculature, which can be assessed for injury or for potential sites of anastomosis in microvascular repair of the missing structures.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Debridement

The conventional wisdom in management of gunshot wounds (GSWs) and other severe facial injuries with extensive tissue maceration is surgical debridement. After the initial encounter and airway management and hemorrhage control, a very conservative surgical debridement is carried out. This initial debridement is performed on only obviously unsalvageable tissues. At the conclusion of the first debridement, an attempt at soft tissue closure is carried out. This is done to obtain tenting of the soft tissue over the exposed bony skeleton and to prevent soft tissue contractures. The patient is transported to the operating room every other day for further conservative debridement, and initial stabilization of the facial fractures. While the surgeon is providing this initial therapy, he/she should be assessing the extent of missing tissue, both hard and soft, and the surgical options available to reconstruct the defect. The reconstructive surgeon should always be planning potential local, regional, and/or distant flaps. This awareness will prevent the unwanted sacrifice of blood vessels that supply potential flaps or possible recipient vessels for later microvascular anastomosis. The end point for the debridement is the establishment of a healthy tissue bed for the eventual final reconstruction.

RECONSTRUCTIVE CONCEPT

The traditional approach to management of defects has been centered on the concept of the reconstructive ladder. This doctrine has at its center the philosophy that the surgeon should carry out the simplest possible procedure to obtain closure of the defect before proceeding to the next “step” and thus more complex surgery. The fallacy of this doctrine is that what is easiest may not necessarily be the best flap, both for the closure of the particular defect and for that patient. The current concept adopted by many reconstructive surgeons is the idea of employing the “best” reconstruction option for the defect, regardless if it is the easiest or the most complex option. This concept has improved the final results in that patients are now spared multiple stage reconstructions with less than optimal outcome, and reconstructed with the most appropriate flap to suit not only the defect but also the patient. The maxillofacial region is rich with potential local flaps for the reconstruction of small facial defects. Similarly, the potential for free tissue transfer is only limited by the patient’s overall injuries, the surgical limitation, and the imagination of the surgeon. The following options are some of the flaps more commonly used by the author and do not represent all the options available for head and neck reconstruction.

LOCAL/REGIONAL

Local flap options are often limited in cases of large soft tissue loss. One of the areas where this may not be the case is in the reconstruction of lip defects. Often, one of the lips is involved and the other is spared. This sparing allows for the use of the uninvolved lip as a donor site for the reconstruction of the affected lip. The other site is the forehead. The paramedian forehead flap may be used in the reconstruction of nasal defects, which can range from small defects to as large as total nasal coverage. Mucosal injuries are often allowed to heal by secondary intention. However, in cases in which significant bulk is missing, a good option is the use of the facial artery musculomucosal flap.

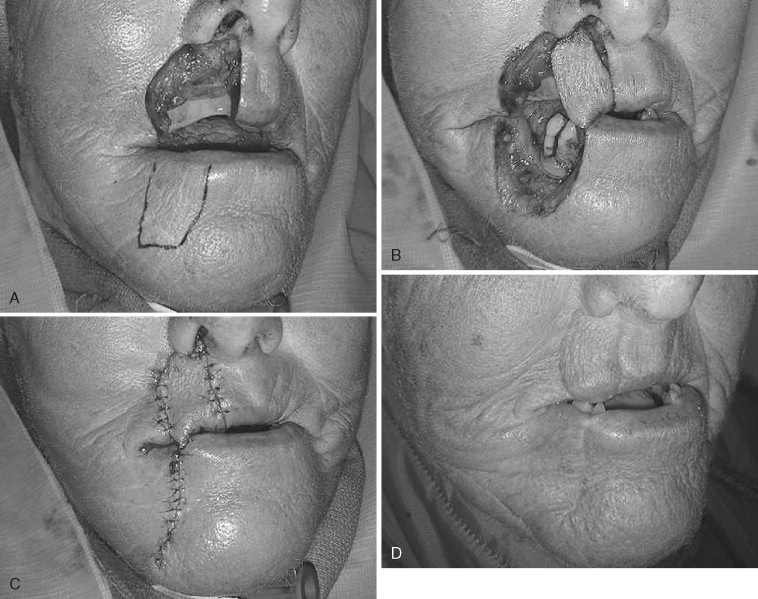

Abbe Flap

The Abbe flap has been in the armamentarium of maxillofacial surgeons for more than a century. It was first described by Abbe in 1898. The flap is based on the superior and inferior labial arteries, which are branches of the facial artery. The utility of this flap cannot be overemphasized given its ability to replace like tissue with like tissue. The author adopts the philosophy of Burget that when the defect is greater than half of a subunit, the subunit should be excised. To improve the final aesthetic outcome, the defect may need to be extended to include the entire aesthetic subunit; this extension is at times difficult to accomplish by the beginning surgeon because of fear of wasting tissues. This excision will allow for a better reconstruction by placing the incisions in a less conspicuous site. Once the defect is outlined, the width of the flap is decreased by approximately half, while maintaining a 1 to 1 ratio of the height of the flap. The ideal rotation of the flap is checked and then the incision is begun on the contralateral side away from the feeding labial artery. The incision is carried out to the full thickness up to about 1 cm of the remaining attachment of the artery and flap. At this point, careful dissection is undertaken to free as much of the muscle as possible to allow for proper arc of rotation, while still protecting the vascular pedicle. The skin is incised up to the vermilion without endangering the vascular pedicle, since it runs on the inner aspect of the lip ( Figure 19-2 ).

With the flap fully mobilized, the surgeon then begins the insetting by closing the mucosa, followed by muscular closure, and last skin closure. If this order of closure is not followed, the surgeon will be unable or severely hindered from closing the mucosa once the muscular and skin closure is completed. The flap is allowed to develop collateral circulation for approximately 3 weeks or more before its release.

Facial Artery Musculomucosal Flap

The facial artery musculomucosal (FAMM) flap was first described by Pribaz and colleagues in 1992. The flap is based on the facial artery and is an intraoral mucosal flap that can be used for a multitude of defects. The flap can be superiorly or inferiorly based and can rotate to reconstruct lip, cheek, floor of mouth, or palatal defects. The harvesting of the flap is first approached by using a portable Doppler probe to outline the path of the facial artery (intraorally). Once the path is marked from the depth of the mandibular buccal vestibule to the maxillary vestibule, the width of the flap is marked. The intended defect size is limited to only 3 cm at its largest so as to minimize scarring and postoperative trismus. The harvesting is done in a straightforward path by incising the marked flap past the buccinator muscle. The vessel is identified, ligated, and divided. Dissection is continued in the direction of the pedicle. Once the harvesting is completed, the donor site is closed in layers, and the flap is mobilized to the site to be reconstructed and is then inset.

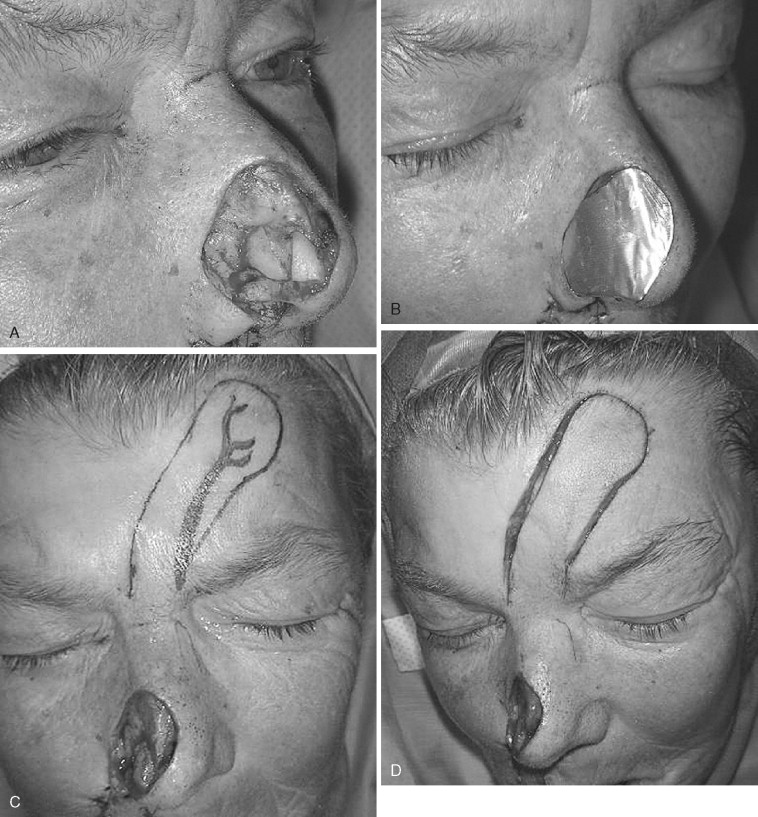

Paramedian Forehead Flap

The paramedian forehead flap is one of the mainstay flaps for nasal reconstruction. This flap is most often used in the reconstruction of oncologic defects but it can also be used in the reconstruction of traumatic defects. The blood supply to the paramedian forehead flap is the supratrochlear artery. The design for this flap is most often based on a predetermined template. The author prefers to use the aluminum casing of suture needles as the material to outline the template for the defect. The template is transferred to the forehead region and the flap is marked. The elevation of the flap is on a subcutaneous plane until about 2 cm above the brow region. At this region the dissection is deepened to the periosteal plane and the flap dissection is completed. Rotation of the flap is checked to eliminate compression and kinking of the vascular pedicle ( Figure 19-3 ). The flap is then inset and, similar to other pedicled flaps, is allowed to develop collateral blood supply for about 3 weeks. It is then detached and the inset completed.

Cervicofacial Flap

The cervicofacial flap is a random flap that can be used to cover cheek defects and/or to bring like tissues to replace the skin component of previously transferred free flaps. The flap is marked from the area of the defect extending posterior and superior to the lateral canthal region. The incision is made to a level above the plane of the canthus and extended to the preauricular region, as with a rhytidectomy incision. The continuation of the incision in the neck is dependent on the extent of the defect to be closed. The incision can be extended to the chest region. The flap is then elevated in a subcutaneous plane and rotated to close the defect ( Figure 19-4 ).

Temporoparietal Fascia Flap

The temporoparietal fascia flap is a thin, pliable flap that may be used for the reconstruction of several facial defects. This flap may also be harvested as an osteofascial flap. Its utility is based on its ease of harvest and reach. It may be used to reconstruct defects of the midface, maxilla, buccal mucosa, floor of mouth, and mandible. The harvest of the flap is first carried out by using Doppler to determine the path of the superficial temporal vessels. Once this is marked, a small strip of hair is shaved along the temporal region in the manner of a bi-temporal flap design. A thin flap is then elevated just below the level of the hair follicles. Care is taken to not injure the vasculature of the flap, which is found directly under the raised scalp flap. Once the desired length and width of the flap are exposed, the temporoparietal fascia is elevated off of the temporalis fascia and transferred to the desired location. When this flap is used for intraoral reconstruction a skin graft is rarely used because the flap will mucosalize. However, when used to provide coverage for facial defects, a skin graft may be used to improve the final cosmetic appearance.

Pectoralis Major Myocutaneous Flap

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses