Introduction

In this study, we explored how others perceive persons with normal occlusion or different malocclusions (open bite, deepbite, underbite, overjet, crowding, and spacing). The objectives were to investigate (1) how occlusion affects others’ perceptions of attractiveness, intelligence, and personality, and their desire to interact in personal and professional settings, and (2) whether these assessments are affected by the target person’s sex or the respondent’s characteristics.

Methods

Survey data were collected from 889 patients or accompanying adults (46% male, 54% female; age range, 18-90 years) who evaluated target photos that had been manipulated to display either a normal occlusion or 1 of 6 malocclusions.

Results

The ratings of attractiveness, intelligence, conscientiousness, agreeableness, and extraversion differed significantly depending on the occlusion status depicted. Persons with normal occlusion were rated as most attractive, intelligent, agreeable, and extraverted, whereas persons with an underbite were rated as least attractive, intelligent, and extraverted. Female targets were rated more positively than male targets. Younger respondents and more educated respondents were more critical in their evaluations than were older and less educated respondents.

Conclusions

Occlusion status affects a person’s perceptions comprehensively. Subjects with normal occlusion were rated the most positively.

The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey III from 1988 to 1991 showed that 57% to 59% of adults had some degree of malocclusion, and only 35% had well-aligned mandibular incisors. More specifically, the data showed that 50% of adults had an excessive overjet, 48% had a deepbite, 6% had a negative overjet or underbite, and 3% had an anterior open bite. Although 2 decades have passed since these data were collected, they still are the most current prevalence data concerning malocclusions among adults in the United States. As evidenced by the prevalence of adults with persistent orthodontic treatment needs, malocclusion is unlikely to self-correct with time, and the complexity can even increase with age. Despite this trend toward increased orthodontic treatment need with age, adults seeking orthodontic treatment comprise only 15% to 25% of all orthodontic patients. Because of these significant percentages, it is important to comprehensively understand how malocclusion might influence others’ perceptions and behavioral intentions to interact with adults with malocclusion.

Prior research showed that a person’s attractiveness has a significant effect on others’ perceptions of that person. Attractive people were considered to be more intelligent and socially competent, to have a more positive personality, to have better social interactions, and to receive more favorable professional ratings. Research also explored the role of malocclusion in determining overall facial attractiveness, as well as determined how orthodontic treatment need might affect a person’s sense of self-worth. These findings suggested that adolescents and adults with malocclusion might have a decreased sense of self-worth, and that their general attractiveness, social acceptability, ability, and personality were judged more negatively. In 1985, Shaw et al showed that malocclusion was influential enough to affect several personality ratings including intelligence, friendliness, and popularity. Therefore, not only do malocclusions reduce the overall facial attractiveness ratings of others, but also malocclusions can lead to psychosocial disadvantages and adverse social reactions that affect patients’ lives. Negative perceptions have been associated with several malocclusions including crowding, deepbite greater than 7 mm, anterior open bite, overjet greater than 9 mm, and underbite (“intention bite”), which has been associated with the perception of an aggressive personality.

A comprehensive analysis of the effects of malocclusion on perceptions must go beyond merely considering ratings of attractiveness and intelligence to thoroughly understanding how malocclusions affect perceptions of a person’s personality traits as well as behavioral intentions to interact with a person. A personality trait is a temporally stable, cross-situational individual difference. One widely accepted model of personality traits is the 5-factor model. The 5 factors described in this model were the result of factor analyses of self-reports and other reports of personality-related adjectives. This theory postulates that the 5 factors of extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, neuroticism, and openness to experience comprehensively describe personality differences. Research showed that these factors can be considered to be universal because they have been found in studies in 6 languages as diverse as German and Chinese. This theory was therefore used to determine which personality characteristics would be included in this study.

In addition to the effects of malocclusion on person perceptions and behavioral intentions, we also explored how the sex of the depicted persons with different malocclusions would shape others’ perceptions. Earlier research showed that females were judged more severely by others, and that a female with an unattractive dental region had a particular disadvantage compared with males. In addition, observer characteristics might also play a role in how a person is perceived. With regard to observer sex and attractiveness ratings, the research findings were inconsistent. Although some authors found that women were more critical, others concluded that men were more concerned with attractiveness and therefore judged more harshly. However, some researchers reported that the observer’s sex had little effect on the ratings given. In addition to sex, other observer characteristics evaluated were ethnicity or race, age, income, educational background, and previous history of orthodontic treatment.

Our objectives in this study were to explore (1) how different malocclusions influence others’ perceptions of attractiveness, intelligence, and personality characteristics (extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, neuroticism, and openness) and behavioral intentions to interact in personal and professional settings; (2) whether male and female targets are rated differently when they have normal occlusion vs different types of malocclusion; and (3) whether observer characteristics such as sex, ethnicity or race, age, income, education level, and history of previous orthodontic treatment shape person perceptions and behavioral intentions.

Material and methods

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board for the Health Sciences at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. The project consisted of 2 pilot studies and 1 quasi-experimental study.

The objectives of the pilot studies were to identify photos of 2 male and 2 female subjects of average attractiveness. Their photos should not be rated too extremely by observers. Faces of average attractiveness were used in the actual experiment to prevent bottom and ceiling effects of ratings.

Data from 101 dental students (51 men, 50 women) were collected for the first pilot study, and data from 29 female dental hygiene students and 104 dental students (56 men, 48 women) were collected for the second pilot study. The second pilot study was conducted because only 1 female photo in the first pilot study was assessed as having average attractiveness.

The pilot data were collected at the end of regularly scheduled classes. The students were informed about the study and volunteered to respond anonymously to a short survey by rating the attractiveness of the depicted students.

The respondents received a 5.5 × 8.5-in booklet that contained frontal facial photographs of 17 persons in the first pilot study and 19 persons in the second pilot study. The photos used in the second pilot study were 16 of the photos from the first pilot study plus 3 additional female photos. One original female photo from the first pilot study was excluded from the second pilot study for logistical reasons. The cover page of the booklet instructed the respondents to rate the attractiveness of each photo on a scale from 1 (unattractive) to 10 (attractive). The facial photos, taken with a white background, showed the nonsmiling faces of white female and male students between the ages of 20 and 30 years who did not wear any glasses or adornments. Each portrayed person had consented to have the photographs taken, altered as needed, and used in the study.

Data were collected from 889 regularly scheduled patients or their accompanying adults at a dental school clinic. Participants had to be able to understand written English and were 18 years of age or older. The participants’ average age was 54.2 years (SD, 17.1; range, 18-90 years), and 46% were male and 54% female. Whereas 84% of the participants were European Americans, 8% were African Americans, 2% were Hispanic or Latino, and 6% were from other backgrounds. Table I provides an overview of their background characteristics.

| General characteristics | Frequencies |

|---|---|

| Sex (n) | |

| Male | 405 (46%) |

| Female | 484 (54%) |

| Age (y) | |

| Mean/range/SD | 54.2/18-90/17.1 |

| Ethnicity or race (n) | |

| European American | 706 (84%) |

| African American | 64 (8%) |

| Hispanic or Latino | 17 (2%) |

| Other | 52 (6%) |

| Education (y) | |

| Mean/range/SD | 13.4/2-30/3.0 |

| Monthly income | |

| No income | 35 (4%) |

| <$1000 | 169 (20%) |

| $1001-$3000 | 344 (41%) |

| >$3001 | 295 (35%) |

| Patient had braces: yes | 97 (11%) |

Regularly scheduled patients or accompanying adults were informed about the study on arrival in a waiting area. Adults who consented to participate completed the survey, placed it in an envelope, and returned it anonymously. The respondents spent approximately 10 minutes responding to the survey. They received a free parking voucher as a token of appreciation.

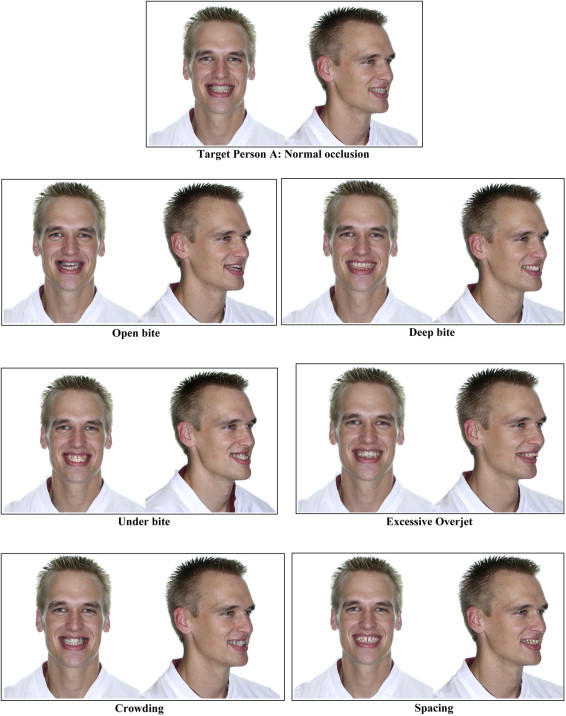

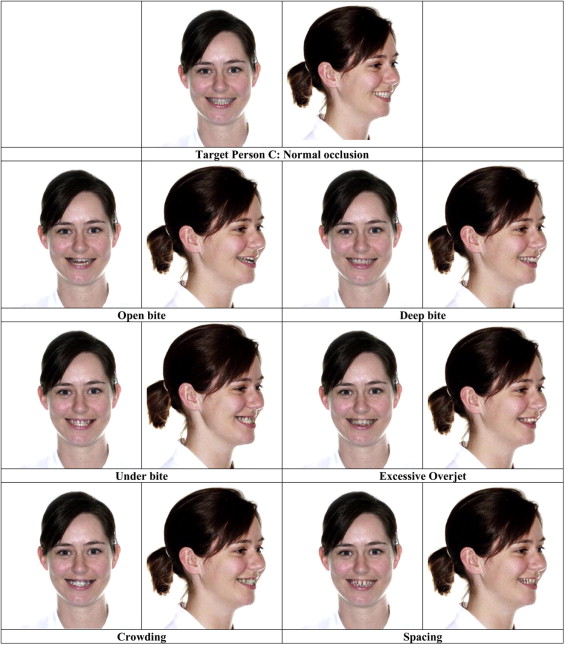

Based on the results of the 2 pilot studies, photos of 2 male and 2 female subjects were identified as the target persons and used in the experimental study. The photos were selected based on the average attractiveness ratings and the fact that they were not rated too extreme by the respondents in the pilot study. Each target person was photographed smiling from a frontal and a three-quarters view. Once these 2 views were obtained, the area inside the borders of the lips was modified (Adobe Photoshop, San Jose, Calif) to show a normal occlusion and 6 malocclusions (open bite, deepbite >7 mm, underbite, overjet >9 mm, crowding, and spacing) for each of the 4 target persons ( Figs 1 and 2 ). For malocclusions that included a skeletal discrepancy, such as severe overjet and underbite, the photographs were also altered to reduce and increase the projection of the chin, respectively.

Each participant received only 1 of the 28 possible versions (4 photos × 7 variations) of the survey to avoid drawing too much attention to the occlusion status and to prevent memory from affecting the ratings of the second set of photos. The survey consisted of 3 sections on 3 stapled sheets of paper, printed on the front and back. The cover page included brief instructions on how to respond to the survey. The first part of the survey (pages 3 and 5) asked the respondents to evaluate the frontal and three-quarters view photographs (printed in color on pages 2 and 4, opposite the questionnaire items) and to rate the photographs on 7-point answer scales for 43 adjective pairs. These adjective pairs were carefully chosen by the researchers with the dependent measures (attractiveness, intelligence, and the 5 personality factors) in mind. Concerning assessing ratings of the 5 personality factors, these 5 factors were chosen based on a well-accepted personality theory. However, the authors of this 5-factor model did not develop a standardized instrument for assessing others’ personalities. The adjective pairs used in this study were therefore selected based on the materials used in an earlier study by Inglehart and Boone for rating health care providers. Because of this process, each of the 5 personality factors was assessed with a different number of adjective pairs because the authors of the original study had included varying numbers of items to measure each factor. The second part of the survey asked the respondents to indicate on a 7-point answer scale (1, “not at all,” to 7, “very much”) how much they agreed with 10 statements about their behavioral intentions to interact with the depicted person in personal and professional settings. The final section of the survey assessed the respondents’ background characteristics (sex, age, ethnicity or race, years of education, and income) and their experiences related to orthodontic treatment.

Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed with SPSS software (version 17.0; SPSS, Chicago, Ill). Descriptive statistics were used to provide an overview of the respondents’ characteristics and the frequencies and average responses to the adjective pair questions and the behavioral intention questions. A factor analysis was used to analyze the factor structure of the 42 adjective pairs and a second factor analysis to analyze the factor structure of the 10 behavioral intention items to identify which items could be combined to construct indexes. The answers to the adjective pair “attractive/unattractive” were not included in this analysis because the answers to this single item served as the indicator of the respondents’ attractiveness ratings. The reliability of the indexes was determined with Cronbach alpha reliability coefficients. The responses of different groups of respondents were compared with univariate analyses of variance (ANOVA). In addition to reporting the significance level of the main effect of “type of occlusion,” post hoc comparisons were used to analyze whether the average ratings under the condition of “normal occlusion” differed significantly from the average ratings of each of the 6 conditions of “malocclusion.” A P value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

To identify the adjective pairs that could be used to construct indexes for the dependent variables of target person’s attractiveness, intelligence, and the 5 personality descriptors of neuroticism, extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, and openness, a factor analysis (extraction method, principal component analysis; rotation method, varimax) was conducted with all adjective pairs except the pair “attractive/unattractive.” This adjective pair was used as the attractiveness indicator. The results of the factor analysis showed that the remaining 42 adjective pairs loaded, as predicted, on 6 factors. The responses to the items loading on each of these 6 factors were averaged to create indexes, which can be interpreted as the 5 personality factors and an intelligence factor. Four items (eg, “unintelligent /intelligent” and “dumb/knowledgeable”) loaded on a factor interpreted as the “intelligence” factor (reliability: Cronbach alpha = .808), 16 items (eg, “dishonest/trustworthy” and “lazy/disciplined”) loaded on the “conscientiousness” factor (alpha = .928), 5 items (eg, “undesirable/desirable” and “not hygienic/hygienic”) on the “agreeableness” factor (alpha = .849), 7 items (eg, “depressed/positive” and “angry/happy”) on the “neuroticism” factor (alpha = .838), 3 items (“unimaginative/creative” and “not artistic/artistic”) on the “openness” factor (alpha = .618), and 3 items (“introverted/outgoing” and “shy/confident”) on the “extraversion” factor (alpha = .708).

A second factor analysis (extraction method, principal component analysis; rotation method, varimax) was conducted with the 10 items used to assess the respondents’ behavioral intentions concerning interactions with the depicted persons. This factor analysis showed that all 10 items loaded on 1 factor. The items were therefore combined into 1 index called “behavioral intentions” (alpha = .959).

Results

A central objective of this study was to determine whether a target person would be perceived differently if his or her photo displayed a normal occlusion or a malocclusion. Table II shows that the attractiveness and intelligence ratings of the depicted persons with normal occlusion and the 6 malocclusions differed significantly. The target persons with normal occlusion were rated as most attractive and most intelligent, and the target persons with an underbite were rated least positively. Concerning the ratings of the 5 personality dimensions, the data showed that the assessments of the target persons’ conscientiousness, agreeableness, and extraversion differed significantly. The targets with normal occlusion were evaluated as most extraverted and most agreeable and conscientious. Target persons with an underbite were rated as the least extraverted, and target persons with generalized spacing received the worst ratings of conscientiousness and agreeableness.

| Characteristics ∗ | Normal occlusion n = 126 |

Malocclusions | P † | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Open bite n = 121 |

Deepbite n = 132 |

Underbite n = 121 |

Overjet n = 133 |

Crowding n = 125 |

Spacing n = 123 |

|||

| Attractiveness | 5.43 | 4.79 | 5.22 | 4.60 | 4.71 | 4.94 | 4.72 | <0.001 a, c, d, e, f |

| Intelligence | 5.43 | 5.04 | 5.26 | 4.91 | 5.17 | 5.12 | 4.97 | 0.01 a, c, e, f |

| Personality traits | ||||||||

| Conscientiousness | 5.18 | 5.21 | 5.02 | 4.92 | 5.20 | 5.08 | 4.86 | 0.047 c, f |

| Agreeableness | 4.36 | 4.04 | 4.15 | 4.00 | 3.93 | 4.15 | 3.92 | 0.039 a, c, d, f |

| Neuroticism | 2.50 | 2.56 | 2.55 | 2.84 | 2.77 | 2.67 | 2.73 | 0.179 |

| Lack of openness | 3.42 | 3.47 | 3.53 | 3.63 | 3.46 | 3.40 | 3.66 | 0.512 |

| Extraversion | 5.21 | 4.91 | 4.87 | 4.61 | 4.79 | 4.92 | 4.77 | 0.019 b, c, d, f |

| Behavioral intention | ||||||||

| Index: desire to interact | 4.75 | 4.65 | 4.51 | 4.25 | 4.54 | 4.42 | 4.37 | 0.089 |

∗ Scores ranged from 1 (lowest expression) to 7 (highest expression) of the characteristic.

† In addition to reporting the significance of the main effect of the factor “occlusion status” in the univariate ANOVA, the results of post hoc comparisons are also reported. A significant difference between the mean in the condition “normal occlusion” and the mean in the respective condition of malocclusion is represented by the letters: a , difference between normal occlusion and open bite; b , difference between normal occlusion and deepbite; c , difference between normal occlusion and underbite; d , difference between normal occlusion and overjet; e , difference between normal occlusion and crowding; f , difference between normal occlusion and spacing.

Concerning the observers’ intentions to interact with the target persons, Table II shows that the intentions to interact with the person with an underbite were again the most negative.

In addition to reporting the significance level of the main effect “type of occlusion,” Table II also reports the findings of post hoc comparisons that analyzed whether the responses in the condition “normal occlusion” differed significantly from the average ratings of each of the 6 conditions of “malocclusion.” The post hoc comparisons of the differences between normal occlusion and open bite were significant for the ratings of attractiveness, intelligence, agreeableness, and tentatively for extraversion ( a in the last column of Table II ). Concerning the average responses under the condition “deepbite,” the post hoc comparisons showed that only the extraversion ratings differed significantly from these ratings under the condition “normal occlusion” ( b in the last column of Table II ). However, the average ratings under the condition “underbite” did differ significantly from the average ratings under the condition “normal occlusion” ( c in the last column of Table II ) as did the average ratings under the condition “spacing” ( f in the last column of Table II ). In addition, the post hoc comparisons of the attractiveness, intelligence, agreeableness, and extraversion ratings under the condition of “overjet” ( d in the last column of Table II ), and the attractiveness, intelligence, and extraversion ratings under the condition “crowding” ( e in the last column of Table II ) differed significantly from these average ratings in the condition “normal occlusion.”

The second objective was to investigate whether the target person’s sex would affect observers’ perceptions of the target persons and their behavioral intentions. Table III shows that the main effect “sex” was significant for all dependent variables other than the personality characteristic “extraversion.” Women were on average more positively evaluated than men. Women were rated as more attractive, more intelligent, more conscientious, less neurotic, and more open to experiences, and the observers desired more strongly to interact with women compared with men.

| Characteristics ∗ | Target sex | Normal occlusion | Malocclusions | P (sex) P (interaction) † |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Open bite | Deepbite | Underbite | Overjet | Crowding | Spacing | ||||

| Attractiveness | Male | 5.19 | 4.57 | 5.14 | 4.21 | 4.41 | 4.54 | 4.69 | <0.001 |

| Female | 5.68 | 5.00 | 5.31 | 4.97 | 5.05 | 5.33 | 4.76 | 0.442 | |

| Intelligence | Male | 5.35 | 4.89 | 5.22 | 4.59 | 4.94 | 4.81 | 4.80 | <0.001 |

| Female | 5.51 | 5.18 | 5.31 | 5.20 | 5.45 | 5.43 | 5.13 | 0.386 | |

| Personality traits | |||||||||

| Conscientiousness | Male | 4.82 | 5.05 | 4.90 | 4.66 | 4.78 | 4.93 | 4.55 | <0.001 |

| Female | 5.58 | 5.36 | 5.16 | 5.15 | 5.70 | 5.22 | 5.19 | <0.055 | |

| Agreeableness | Male | 4.17 | 3.88 | 4.16 | 3.73 | 3.63 | 4.03 | 3.85 | <0.001 |

| Female | 4.58 | 4.19 | 4.15 | 4.25 | 4.28 | 4.26 | 4.00 | 0.292 | |

| Neuroticism | Male | 2.63 | 2.70 | 2.57 | 3.04 | 2.99 | 2.80 | 2.84 | <0.001 |

| Female | 2.36 | 2.41 | 2.53 | 2.64 | 2.49 | 2.54 | 2.62 | 0.813 | |

| Lack of openness | Male | 3.55 | 3.49 | 3.57 | 3.71 | 3.74 | 3.69 | 3.80 | <0.001 |

| Female | 3.29 | 3.45 | 3.47 | 3.55 | 3.13 | 3.10 | 3.52 | 0.323 | |

| Extraversion | Male | 5.27 | 4.86 | 4.86 | 4.51 | 4.70 | 5.00 | 4.74 | 0.591 |

| Female | 5.15 | 4.97 | 4.89 | 4.71 | 4.89 | 4.84 | 4.81 | 0.888 | |

| Behavioral intention | |||||||||

| Index: desire to interact | Male | 4.45 | 4.36 | 4.31 | 3.77 | 4.17 | 3.90 | 4.07 | <0.001 |

| Female | 5.05 | 4.93 | 4.76 | 4.68 | 4.98 | 4.96 | 4.69 | 0.538 | |

∗ Scores ranged from 1 (lowest expression) to 7 (highest expression) of the characteristic.

† The first P value in each cell refers to the significance level for the main effect of sex, and the second P value in each cell refers to the significance level of the interaction effect between sex × malocclusion.

The third objective focused on whether observers with different characteristics varied in their evaluations of adults with different occlusions. The effects of the observers’ sex, ethnicity or race, age, income, educational level, and history of previous orthodontic treatment were assessed. ANOVA tests with “type of occlusion” and each of these observer characteristics as the second factor were conducted to explore this third objective. The results showed that the respondents’ sex had no impact on their ratings of the targets with the different occlusions, nor did their ethnicity or race, income, or previous history of orthodontic treatment. However, when the responses of younger respondents (<55 years of age) were compared with those of older respondents (≥55 years), several significant results were found. As can be seen in Table IV , older respondents rated the target persons as more attractive, more intelligent, more conscientious, and more extraverted. In addition, the observers’ level of education also affected some ratings. Table V shows that the observers with less education (high school diploma or less, 1-12 years of education) were less critical than the observers with more than a high school education (≥13 years of education) in their evaluations of the targets. Less educated respondents rated the targets as more intelligent, more conscientious, more agreeable, and more open than did respondents with 13 or more years of education. In addition, less educated respondents generally reported a stronger average desire to interact with the target persons overall than did the more educated respondents.