Cervical rejuvenation encompasses a myriad of surgical alternatives. Cervicofacial liposuction is an excellent surgical procedure that is performed to rejuvenate the submental, submandibular, and jowl regions. Removal of adipose tissue from the submental region to the thyroid cartilage produces more of a right-angled appearance in the cervical region.

In young patients (teens to mid 30s), isolated cervicofacial liposuction yields an excellent result. In middle-aged individuals, cervicofacial liposuction alone may lead to compromised results. Platysmaplasty and/or a skin-tightening procedure may have to be performed for acceptable results to be attained. In the typical aged face, cervicofacial liposuction does not achieve desired harmony between the face and the neck, instead producing an unnatural-appearing result. Additional facial rejuvenating procedures such as face-lifting, skin resurfacing, or blepharoplasty would have to be added for a harmonious result to be achieved.

Cervicofacial liposuction exhibits its greatest effectiveness in contouring of the neck and jowl regions in patients without platysmal pathosis, cervical dermatochalasia, or ptosis. In those who exhibit platysmal hypertrophy, laxity, and/or banding, cervicofacial liposuction by itself may yield less than desirable results. This is particularly true in older individuals, who also may present with excessive laxity of the cervical skin. These patients may have to undergo additional facial recontouring procedures to attain acceptable results.

HISTORY

Maliniak first described excision of submental fat and skin in 1932. Removal of submental fat, use of mylohyoid muscle flaps, and imbrication of platysmal muscle edges were first described by Padgett and Stephenson in 1948. Davis described the removal of submental fat by curette in 1955. Adamson explained surgical correction of the turkey gobbler deformity in 1964. Investigators excised an elliptical portion of excess neck skin at the level of the hyoid bone, and underlying fat pads were resected completely through the same incision. Millard in 1972 advocated horizontal skin incisions for removal of submental and submandibular fat pads in conjunction with standard rhytidectomy. Schrudde in 1972 introduced a new closed procedure, lipexheresis, which consists of excision of adipose tissue with a sharp uterine curette introduced through a small skin incision. In the late 1970s, Illouz clearly established liposuction as a viable surgical alternative for the contouring of unwanted fat deposits. Illouz advocated other technical refinements such as the development of a honeycombed tunnel network within the suctioned area of adiposity. This technique preserves vascular and lymphatic continuity between the deep adipose tissue and the skin. He also stressed that the lumen of the canula should be oriented away from the overlying dermis. When Illouz’s techniques were applied, problems associated with other techniques, such as skin necrosis, long-term edema, contour irregularities, and dermal scarring, were reduced.

SELECTION OF PATIENTS

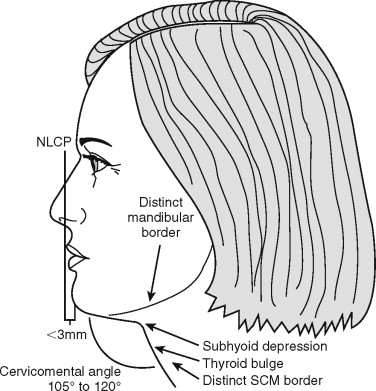

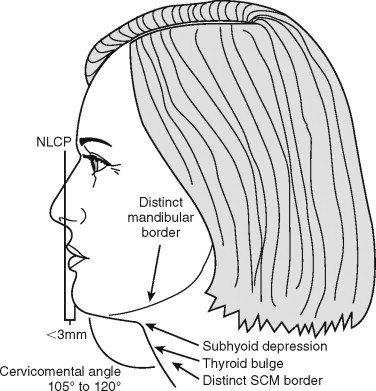

Selection of patients for cervicofacial liposuction should always begin with a thorough discussion with the patient about concerns and expectations. Differentiating realistic from unrealistic expectations is essential if patients are to be happy with treatment outcomes. Not everyone who presents for a surgical procedure is a good surgical candidate. Careful and complete examination of the cervical region is required. To understand the process involved in the selection of patients, youthful attractive neck characteristics should be described. These characteristics include good cervical skin elasticity, distinct inferior mandibular border, cervical-submandibular angle of approximately 115 degrees, adequate mandibular length and projection, visible anterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle, and high and posterior hyoid bone position ( Figure 28-1 ). The smoother the cervical skin and the greater its elasticity, the better the potential result will be. Anatomic features that may lead to less than desirable results include retrogenia/micrognathia, a cherubic face, low and anterior hyoid bone position, ptotic submandibular glands, significant loss of cervical skin elasticity, a greater proportion of subplatysmal fat, platysmal banding/laxity, and little to no cervical subcutaneous fat.

Differential diagnosis in the proximal submental region—an area bounded superiorly by the submental crease, inferiorly by the thyroid cartilage, and laterally by the anterior belly of the digastrics—in terms of preplatysmal versus subplatysmal fat deposition is very important. Clinically, differentiation is achieved via palpation provided in concert with muscle contraction maneuvers. Three such maneuvers are (1) palpating the submental region with the patient grimacing, (2) palpating with the patient clenching the teeth and the tongue pressed against the incisors, and (3) flexing the neck with palpation of the submental region. The third maneuver should be compared with palpation of the submental region with the head in neutral position. Generally, subplatysmal fat is easier to grasp when the neck muscles are in a relaxed state. Preplatysmal liposity is easier to differentiate with the muscles contracted. Preoperative palpation of preexisting fat deposits allows the surgeon to gather information that will contribute to a favorable or compromised postoperative result.

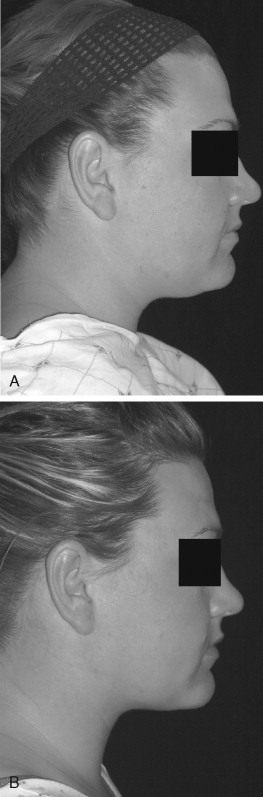

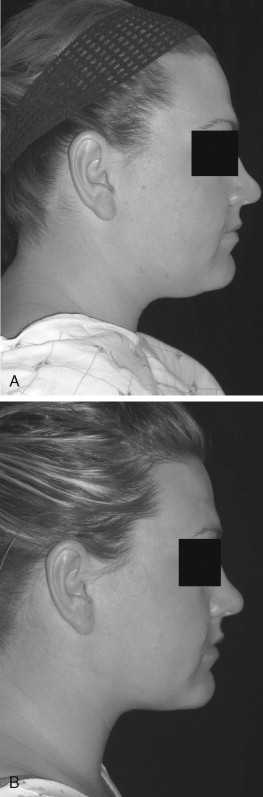

Fat deposits that may lead to positive surgical results with cervical liposuction consist of rounded, palpable, preplatysmal deposits in the proximal submental and/or submandibular region ( Figure 28-2 ).

When a potential patient is evaluated for consideration of cervicofacial liposuction, attention must be given to the jowl region. Two theories on the origin of the jowl have been put forth. The first states that “jowling” is cheek fat that has fallen as the result of relaxation of the masseteric-cutaneous ligaments and then was arrested anteriorly by the perioral cutaneous ligament system. The second theory is that jowling is a deposit of preplatysmal fat that is rounded and protrudes as a definite contour bulge. Type I jowling is seen in younger individuals. This type of jowling is full and rounded, consistent with preplatysmal fat deposits. Type II jowling usually occurs in older individuals. This is caused by relaxation of the SMAS/masseteric ligament and of the skin elastic fiber network. Differentiation between type I and type II jowling is accomplished via simulation of a face-lift; this results in resolution of type II jowling but little to no resolution of type I jowling.

A helpful adjunct and an important communication tool in patient selection is the use of facial computer imaging. Subtleties in anatomic variations can be discussed more easily by the patient and the doctor while profile and frontal views are presented on the monitor. Many patients never view their profile view in such a way that it can be observed with the aid of a computer imaging system. Anatomic limitations and expectations can be discussed more completely. When the computer imaging system is used, it is important not to image the patient to a result that is not surgically attainable. It is also important to remind the patient that use of the computer imaging system is not a guarantee of surgical results, it merely provides simulation of the desired postoperative result; actual results may vary. The computer imaging system leads to improved standardization of preoperative and postoperative photos, allowing for similar magnification and head position.

SELECTION OF PATIENTS

Selection of patients for cervicofacial liposuction should always begin with a thorough discussion with the patient about concerns and expectations. Differentiating realistic from unrealistic expectations is essential if patients are to be happy with treatment outcomes. Not everyone who presents for a surgical procedure is a good surgical candidate. Careful and complete examination of the cervical region is required. To understand the process involved in the selection of patients, youthful attractive neck characteristics should be described. These characteristics include good cervical skin elasticity, distinct inferior mandibular border, cervical-submandibular angle of approximately 115 degrees, adequate mandibular length and projection, visible anterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle, and high and posterior hyoid bone position ( Figure 28-1 ). The smoother the cervical skin and the greater its elasticity, the better the potential result will be. Anatomic features that may lead to less than desirable results include retrogenia/micrognathia, a cherubic face, low and anterior hyoid bone position, ptotic submandibular glands, significant loss of cervical skin elasticity, a greater proportion of subplatysmal fat, platysmal banding/laxity, and little to no cervical subcutaneous fat.

Differential diagnosis in the proximal submental region—an area bounded superiorly by the submental crease, inferiorly by the thyroid cartilage, and laterally by the anterior belly of the digastrics—in terms of preplatysmal versus subplatysmal fat deposition is very important. Clinically, differentiation is achieved via palpation provided in concert with muscle contraction maneuvers. Three such maneuvers are (1) palpating the submental region with the patient grimacing, (2) palpating with the patient clenching the teeth and the tongue pressed against the incisors, and (3) flexing the neck with palpation of the submental region. The third maneuver should be compared with palpation of the submental region with the head in neutral position. Generally, subplatysmal fat is easier to grasp when the neck muscles are in a relaxed state. Preplatysmal liposity is easier to differentiate with the muscles contracted. Preoperative palpation of preexisting fat deposits allows the surgeon to gather information that will contribute to a favorable or compromised postoperative result.

Fat deposits that may lead to positive surgical results with cervical liposuction consist of rounded, palpable, preplatysmal deposits in the proximal submental and/or submandibular region ( Figure 28-2 ).

When a potential patient is evaluated for consideration of cervicofacial liposuction, attention must be given to the jowl region. Two theories on the origin of the jowl have been put forth. The first states that “jowling” is cheek fat that has fallen as the result of relaxation of the masseteric-cutaneous ligaments and then was arrested anteriorly by the perioral cutaneous ligament system. The second theory is that jowling is a deposit of preplatysmal fat that is rounded and protrudes as a definite contour bulge. Type I jowling is seen in younger individuals. This type of jowling is full and rounded, consistent with preplatysmal fat deposits. Type II jowling usually occurs in older individuals. This is caused by relaxation of the SMAS/masseteric ligament and of the skin elastic fiber network. Differentiation between type I and type II jowling is accomplished via simulation of a face-lift; this results in resolution of type II jowling but little to no resolution of type I jowling.

A helpful adjunct and an important communication tool in patient selection is the use of facial computer imaging. Subtleties in anatomic variations can be discussed more easily by the patient and the doctor while profile and frontal views are presented on the monitor. Many patients never view their profile view in such a way that it can be observed with the aid of a computer imaging system. Anatomic limitations and expectations can be discussed more completely. When the computer imaging system is used, it is important not to image the patient to a result that is not surgically attainable. It is also important to remind the patient that use of the computer imaging system is not a guarantee of surgical results, it merely provides simulation of the desired postoperative result; actual results may vary. The computer imaging system leads to improved standardization of preoperative and postoperative photos, allowing for similar magnification and head position.

PREOPERATIVE PREPARATION

The presurgical visit/counseling appointment is vital for preparing the patient for the surgical procedure and the postoperative course. This visit should include a thorough review of the preoperative/postoperative instruction form, as well as the consent form. Expectations should be delineated clearly for the patient. It is helpful to have the patient’s caregiver attend the presurgical counseling appointment. A complete history and physical examination should be performed, along with a review of the patient’s medications (both prescribed and over the counter). Homeopathic/herbal medications should be identified. Any medications that may increase bleeding or that may alter anesthetic delivery or the postoperative course should be held. Medications to be taken on the morning of the procedure should be reviewed. Many patients have greater concern with regard to anesthesia delivery and associated risks than regarding the procedure itself. A phone call from the anesthesia provider can alleviate some of the patient’s stress and anxiety regarding the anesthetic. The patient should be given phone number(s) that can be used to contact the treating doctor in case of questions, concerns, or an emergency. Methods that can be used to decrease bruising and swelling should be discussed with the patient.

In our office, patients stop all medications, including homeopathics, which may increase bleeding, 2 weeks before the procedure. They take bromelain 500 mg, one by mouth two times a day, starting 2 weeks before the procedure and continuing for 1 week afterward. Arnica is taken starting on the night before the procedure and continuing for 4 days afterward. We use head of bed elevation for 1 week postoperatively; ice is used for the first 4 days, and the switch is made to warm moist heat on the fifth day. Arnica gel is used to treat any ecchymosis in the cervical region (five times/day) until the bruising has subsided. Physical exertion, which increases blood pressure, is avoided for at least 2 weeks after completion of the procedure.

SURGICAL TECHNIQUE

Financial commitments should be taken care of before the day of surgery arrives. The patient’s questions should be answered, as should the questions of the caregiver. Expectations again should be reviewed with the patient.

Cervical markings include the jowl region if it is being treated, the inferior mandibular border, the anterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle, the angle of the mandible, the level of the hyoid bone, localized areas of liposity, and planned incision sites ( Figures 28-3 through 28-5 ). Incision length should be slightly longer than the width of the cannula. Because of repetitious back and forth movement of the cannula, a narrow access opening may produce a friction burn on the skin surrounding the incisional margins. This can lead to an unacceptable scar. Two standard markings for incision sites are found in the submental region, laterally positioned: incisions at the right and left lateral superior cervical borders, at the intersection of the anterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle, and the angle of the mandible ( Figure 28-6

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses