Chapter 24 Laser-assisted uvulopalatoplasty: techniques and results

1 INTRODUCTION

Laser-assisted uvulopalatoplasty (LAUP) is a surgical procedure for the treatment of snoring and mild obstructive sleep apnea hypopnea syndrome (OSAHS) that involves a sequential reduction and reshaping of the tissues of the uvula and soft palate. Initially described by Dr Yves-Victor Kamami in 1986, LAUP has been widely performed in the United States since 1993 to remove excessive vibratory tissue of the velopharynx.1 This procedure can often be performed in the office setting under local anesthesia in one to four stages that are typically 6 weeks apart.

2 PATIENT SELECTION

A complete head and neck physical examination should include calculation of a Body Mass Index (BMI), measurement of the neck circumference, and flexible laryngo-scopy. During an exam for all sleep disordered breathing patients, the surgeon must attempt to identify the site or sites of potential obstruction. All patients considering LAUP should also undergo some formal objective sleep assessment. The Standards of Practice Committee of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine recommends a preoperative polysomnogram or cardiorespiratory study prior to LAUP.2

There are several key features that can help a practitioner identify the ideal patient for LAUP. First, polysomno-graphy should reveal the patient to either be a non-apneic snorer or have mild obstructive sleep apnea. Although some studies have shown benefit in patients with moderate and severe OSAS, the long-term outcomes in the improvement of objective indices are controversial. Although the American Academy of Otolaryngology – Head and Neck Surgery declared that LAUP is considered a part of the comprehensive management of adults with OSAHS in 1997, the American Academy of Sleep Medicine did not recommend LAUP for the treatment of sleep-related breathing disorders in 2000.3

A third important selection factor is the patient’s BMI. Rollheim and colleagues were able to demonstrate a statistically significant difference in snoring outcomes 3 months after surgery in patients with a BMI less than 28 kg/m2 as compared to those with a BMI greater than or equal to 28 kg/m2.4 This disparity is most likely related to a greater incidence of obstruction at levels other than the soft palate in patients with a higher BMI, and thus persistent snoring.

There are also several more subtle patient factors to consider in patient selection. Patient co-operation is essential tosuccess if the procedure is to be performed in an outpatient setting. A nervous patient or one with an uncontrollable gag reflex may not be able to tolerate one, or even several, procedures. A small mouth opening or trismus may limit the surgeon’s access to the oropharynx. Lastly, any medical condition, such as a hemostatic disorder, that may decrease the safety of the procedure should be considered a relative contraindication. In the above circumstances, the procedure alternatively may be conducted in the operating room under general anesthesia.

3 PROCEDURE

When initially described by Kamami, the LAUP procedure consisted of two paramedian vertical incisions extending superiorly from the free edge of the soft palate.5 The uvula was largely resected in order to reshape a new, shorter one. This French method was later modified by Woolford and Farrington.6 Their British technique involved vaporization of a strip of mucosa from the uvula to the hard palate. This area is left bare to contract and scar, resulting in increased rigidity of the velum soft tissues. The authors prefer to utilize both modifications, often in a sequential, staged fashion. The following procedure is described with a CO2 laser, but other lasers and cutting/coagulating instruments can also be used, such as electrocautery.

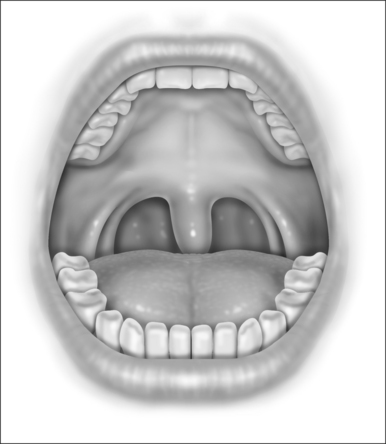

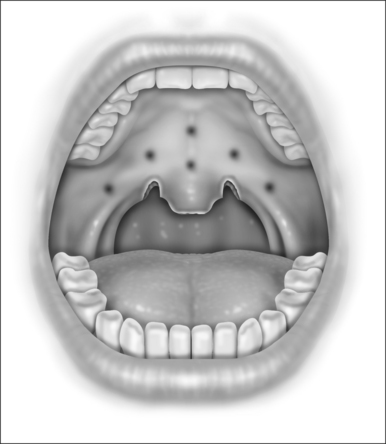

With the patient in the upright, sitting position, a topical anesthetic spray (benzocaine) is generously applied to the oropharynx (Fig. 24.1). Next, lidocaine 1% with epinephrine (1:100,000) is infiltrated into the base of the uvula, posterior soft palate, and the superior aspect of the tonsillar pillars (Fig. 24.2). The injected volume is small (approximately 3 ml) since soft tissue distortion and added water content may compromise the surgeon’s ability to precisely shape the palate. To minimize the painful burning associated with infiltration, the lidocaine may be mixed with bicarbonate solution (9:1 ratio) prior to injection. Further anesthetic may be readministered to alleviate any discomfort during the procedure.

The authors use a CO2 laser to perform the surgery (Lumenis 30-C CO2 Laser, Lumenis, Inc, New York, New York). Lasers of other wavelengths can be used as well. The hand piece has a ‘backstop’ that protects the posterior pharyngeal mucosa from inadvertent injury. A typical laser setting is 20 watts with a focused beam in a continuous mode. The patient and all members of the surgical team must wear eye protection prior to laser deployment.

Initially, the laser is used to create vertical trenches in the soft palate on either side of the root of the uvula. From inferior to superior, a through-and-through incision cutting the oral and nasal mucosa of the soft palate and the intervening soft tissue is made (Fig. 24.2). The length of the trench should be guided by the patient’s anatomy. Typically, the palatal musculature is not exposed. The tip of the uvula is obliterated and made to take on the desired contour (a scanning beam is helpful but not essential for this).

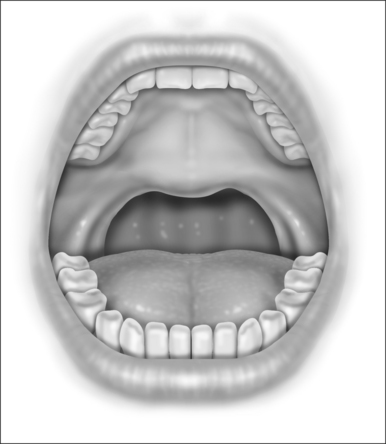

Next, the thickness of the uvula and free edge of soft palate is reduced by excision of the submucosal tissue and part of the uvularis muscle. The anterior uvular mucosa is grasped and rotated superiorly so that the tissue between the oral and nasal mucosa can be reduced with a scanning laser beam. By ‘fish mouthing’ the uvula, the anterior and posterior mucosa are left intact and will heal with minimal granulation at the free edge. These tissues then subsequently scar and contract over the subsequent weeks (Fig. 24.3).

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses