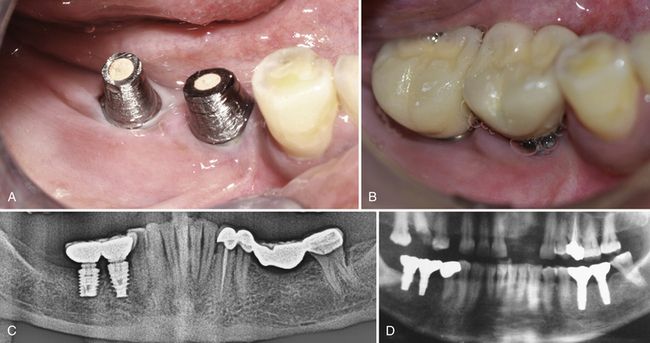

Fig 1.1 Two implants inserted 20 years back in the anterior mandible have maintained the bone volume and prevented the further bone loss in the region while in the other part of the jaw, the patient has lost most of the bony ridge.

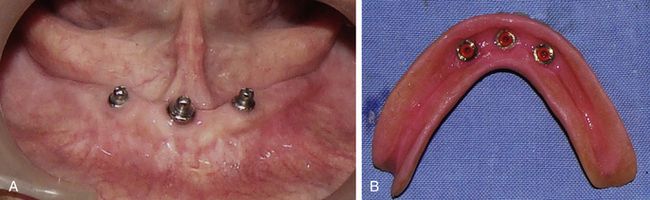

Fig 1.2 (A and B) Dental implants are the most successful and preferred option to retain the loose dentures.

Fig 1.3 (A–C) In cases where no teeth or no firm teeth are available to be used as the abutments to support the conventional fixed bridge, the implant is the only option to deliver a fixed prosthesis. (D) Even in the cases where the dental bridge is possible, the implant prosthesis should be preferred as it does not need to cut down adjacent healthy teeth and also prevents further ridge loss.

History of dental implants

The history of dental implants is believed to have begun as far back as in the seventh century. In the 1930s, dental implants (in their original form, made of seashells) were found in Mayan burial archeological sites, placed in a young woman’s jawbone.

Modern implants had their origin in the discovery by a Swedish professor of Orthopaedics named Branemark, who found that titanium (a very strong and noncorrosive metal) attached itself to a bone when it was implanted into it. During one of his experiments, he embedded titanium devices into rabbit’s leg bones to study bone healing. After a few months, he tried to remove these expensive devices and when he could not, he noticed that the bone had attached itself to the metal. He eventually decided that the mouth was far more practical than the leg for his experiments, as it was easier to watch the progress and there were more toothless people than people with serious joint problems. He called the attachment of the titanium to the bone ‘osseointegration’ and in 1965 he used the first titanium dental implant in a human volunteer.

Over the next few years, he published a lot of research on the use of titanium dental implants, and in 1978 he commercialized the development and marketing of his titanium dental implants. Over 7 million implants under his brand name have been placed. Needless to say, there are other dental implant companies that have used his patent.

Looking at the technology involved and the high success rates of dental implants, it is hard to believe that the history of dental implants goes back only 40 years.

It did not take long to realize the enormous potential of this technique. Dr Branemark began focussing on how he could use osseointegration, to help humans. During his studies, he found that titanium screws could serve as bone anchors for teeth.

Titanium, researchers came to realize, was the only consistently successful material for dental implants. Before Dr Branemark’s work, other doctors had been toying with the idea of dental implants for years. A most of other metals, including silver and gold, had failed. Even human teeth (from donors) were tried.

Dr Branemark continued his studies for nearly three decades. His fellow scientists were sceptical, so he conducted numerous tests, including some on humans, before he published his findings in 1981.

After scientific scrutiny of Dr Branemark’s paper, medical confidence in the procedure grew. Guidelines for implantology were set during the Toronto Conference in Clinical Dentistry in 1982. The standardization of the process during the conference proved to be the jump-start that the dental implant needed. The public began to accept that dental implants were safe.

Commercial oral implantology grew during the 1980s. Osseointegration was being used to permanently fix an individual tooth into the patient’s mouth. Implants proved to be successful in over 90% of cases. The modern dental implant had arrived!

Over the next two decades, technology continued to improve the process. For instance, slight modifications to the titanium used decreased healing time. As time goes by and as the practice of dentistry advances, patients will continue to see dental implants becoming quicker, easier, and less painful.

Fundamental science

Definition of osseointegration

PI Branemark and associates in 1986 defined the osseointegration of the implant as “direct structural and functional connection between ordered, living bone and the surface of a load-carrying implant.”

SG Steinemann and associates in 1986 simplified the definition of osseointegration as “direct contact between bone and an implant surface.”

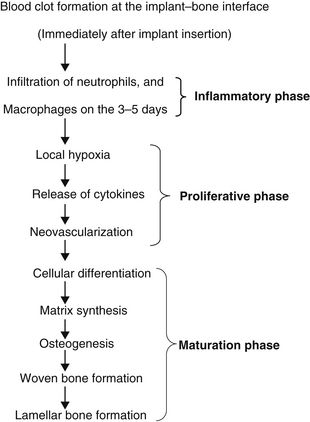

Phases of implant osseointegration

Immediately after the implant is inserted into the jawbone, the peri-implant bone passes step by step, through different phases of histological change, to reach the final stage of osseointegration of the implant with the surrounding bone (< ?xml:namespace prefix = "mbp" />

Clinical evidence of successful osseointegration

• Implant is not mobile when tested clinically

• Implant is asymptomatic – absence of persistent signs and symptoms, such as pain, infections, etc.

• Stable crestal bone levels – annual rate of bone loss should be less than 0.2 mm after the first year in function

• Increasing mineralization of the newly-formed bone at the implant surface

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses