Oral and maxillofacial surgeons routinely restore form and function to injured faces, surgically treat neoplastic masses, and correct dentofacial deformities. Surgeons are technically trained to perform surgery and academically schooled to decide when and what type of surgery is indicated. Surgical training has traditionally centered on honing manual skills, securing patient care competency, and developing practice management expertise. Clearly trauma surgeons are focused (as they should be) on “surgical”-related needs of victims and generally are not involved in other important aspects of meeting patient’s needs. Contributing to the comprehensive rehabilitation of the facial trauma patient is also the surgeon’s responsibility and is as important to the future health and well-being of the victim as is placing plates and screws to reduce and fix facial injuries.

Understanding the psychosocial consequences of trauma and treating traumatic injuries are elements of patient care that must be equally attended to by trauma caregivers. Bodily trauma produced by violence has a startling effect on mental life. Each year approximately 2.5 million Americans are hospitalized after sustaining traumatic physical injuries. An investigation to comprehensively screen for posttraumatic symptomatic stress or identified predictors of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) reported that 73% of 101 surgical inpatients screened positive for high levels of symptomatic stress and/or substance intoxication. At 1, 4, and 12 months after the injury, 30-40% reported symptoms consistent with a diagnosis of PTSD. High in-hospital PTSD symptom levels were the strongest and best predictor of persistent symptoms over the course of the year. Greater prior trauma, stimulant intoxication, and female gender were also associated with higher symptom levels. Increasing injury severity, however, was not associated with higher PTSD symptom levels.

A victim of domestic violence with facial injuries requires much more rehabilitation than just physical injury repair. Domestic violence against women in Bosnia and Herzegovina was studied in the Tuzia Canton region in the period from 2000 to 2002. The authors concluded the domestic violence in various forms had long-term consequences on mental health of women and should be taken into account when treating women with war-related trauma.

Successful patient care outcomes cannot simply be measured by properly reduced and fixated facial fractures. Discharging a battered spouse after treatment back to a dangerous environment clearly represents a therapy compromise that may result in a life-threatening tragedy. Domestic violence is an important health problem that occurs more frequently than expected. “Fractured part” focus is not the correct surgeon mind-set. Rather, a “comprehensive patient rehabilitation” philosophy should be the central theme of care. As an important public health problem, domestic violence requires a multi-disciplinary approach to understand its causes and to plan preventive measures.

PHASES OF COMPREHENSIVE PATIENT CARE

Comprehensive patient care is best described as the evaluation and actions by the team providing care of all the critical elements necessary to return the accident victim to his pre-injury state of health or better well-being. All-embracing management of the injured involves attention to pre-injury conditions, accident circumstances, psychosocial issues, nutrition, home health care, peri-operative medical management, surgical care, and societal concerns (care expenses, return to gainful activity, short- and long-term societal burdens). Phases of comprehensive patient care are presented in Box 22-1 . Diverse elements of treatment must be integrated and changes in the patient’s condition monitored to allow the trauma team to best respond to the victim’s needs.

-

Timely repair of facial injuries

-

Minimize surgical risks to the patient

-

Minimize anesthetic risks to the patient

-

Minimize perioperative risks to the patient

-

Comprehensive rehabilitation of the trauma victim

-

Return the patient to gainful activity

-

Prudent use of health care resources

ACCIDENT CIRCUMSTANCES

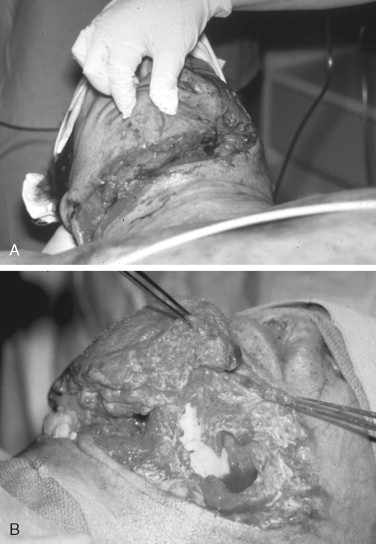

Obtaining and understanding the events and the mechanism of injury of an accident is an essential first step in the process of the definitive management of the facial trauma patient. Accident events that portend multisystems injuries or the likelihood of a specific injury pattern help the examiner to focus on anatomical sites and improve diagnosis and test ordering. Liver is the most commonly affected organ in high-speed motor vehicle crashes (35%), followed by spleen (32%) and small bowel (30%) following blunt abdominal trauma. Head and maxillofacial injuries, particularly midface injuries, are common findings after all-terrain vehicle (ATV) accidents. Orbital trauma with serious globe injury was a striking feature in a study of 72 ATV accidents ( Figure 22-1 ). Interviewing informed witnesses, including professional accident responders who participated in the extrication of the victim at the accident scene, can provide valuable insight into the mechanism of injury ( Figure 22-2 ). High-velocity blunt and projectile injuries are predictive of extensive facial wounding and/or the potential for deep occult injury ( Figures 22-3 and 22-4 ). Facial burns may be related to airbag deployment. Post-injury facial wound infections may be increased when the victim was pulled from a heavily polluted pond that contaminated open fractures.

PRIMARY SURVEY

Airway assessment and restoration of ventilation are critical first steps in the management of a trauma patient and require the highest priority in the initial assessment of the accident victim. A secure airway is fundamental to all resuscitation and long-term care efforts. Integrating respiratory concerns beyond establishing effective ventilation during the primary survey is ongoing through all phases of care. Emergency airway management of a traumatized patient in the early stages of extrication, transport, and resuscitation justifiably commands much of the emphasis. Airway and ventilation must also be considered in the intraoperative and postoperative management of the facial trauma patient. Choosing a method for acute airway support may be influenced by the anesthetic requirements of facial fracture repair and associated systemic conditions that may contribute to postoperative ventilation problems.

Anticipating airway inadequacy before respiratory failure and arrest are imminent is the key to successful and predictable respiratory control. Predictors of respiratory distress and/or ventilation difficulties are presented in Box 22-3 . Attention to the airway should be heightened when multiple factors known to contribute to airway and ventilation difficulties are present ( Figure 22-5 ). Surgical airway management may be introduced early in treatment when the confluence of immediate, intraoperative, and postoperative ventilation needs suggest that a protracted period of airway support is likely.

-

Short neck

-

Obesity

-

History of snoring or obstructive sleep apnea

-

Midface trauma

-

Mandibular symphysis or condyle fractures

-

Intraglossal bleeding

-

Anemia or hypovolemia

-

Chest wall or pleural injury

-

Intracranial injury

-

Drug or alcohol depression

SECONDARY SURVEY

Trauma care has a certain element of drama and anxiety that surrounds the early evaluation and management of accident victims. The primary survey and the subsequent interventions that follow save lives and help to lessen the untoward sequelae of failing organ systems and cardiovascular instability. The maxillofacial surgeon’s role in early facial trauma management of the multisystems-injured patient usually is limited to airway management and control of facial bleeding by largely non-invasive means. The secondary survey is more critical to the definitive diagnosis of facial injuries and establishing the timing and integration of facial trauma care with the treatment of other injuries. Facial trauma repair usually does not require emergent treatment once an airway has been secured and aggressive head and neck bleeding has been resolved. CT scan imaging of the head, face, and neck will confirm and clarify suspected facial fracture sites and contribute to the future treatment planning of facial injuries. A comprehensive review of the victim’s medical history may prompt a thorough cardiovascular workup that explains an unwitnessed fall by a senior citizen or influence a delay in facial trauma repair in an unstable patient.

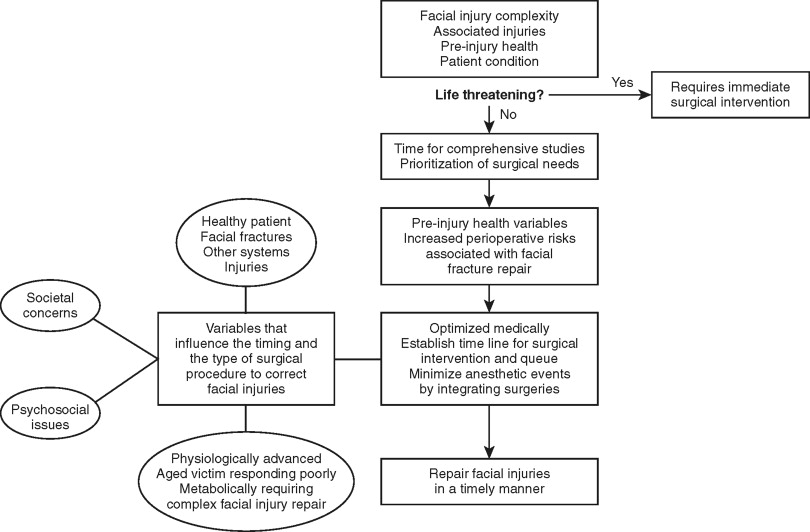

STAGE 1 TREATMENT PLANNING

Facial trauma more commonly occurs in young healthy males who sustain isolated facial fractures. Youthfulness suggests pre-injury good health, the prospects of a relatively straightforward postoperative course, an early return to gainful activities, and minimal need for integrated care. Comprehensive treatment planning for the facial trauma patient may be viewed as a progression of priorities that are constantly changing in rank order or are added or removed during the course of patient care. The more complex and serious injuries require more intense care over a longer period of time and more integrated planning. Surgical options and the timing of facial injury repair may be heavily influenced by new and pre-injury medical conditions, psychosocial issues, societal needs, and the complexities of postoperative care ( Figure 22-6 ).

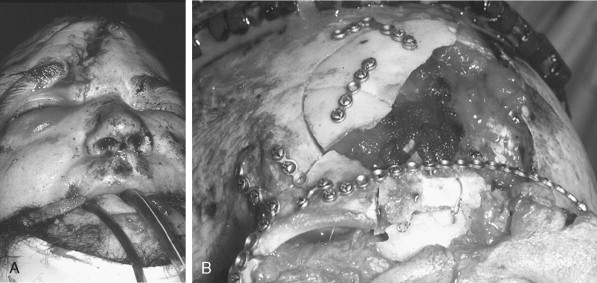

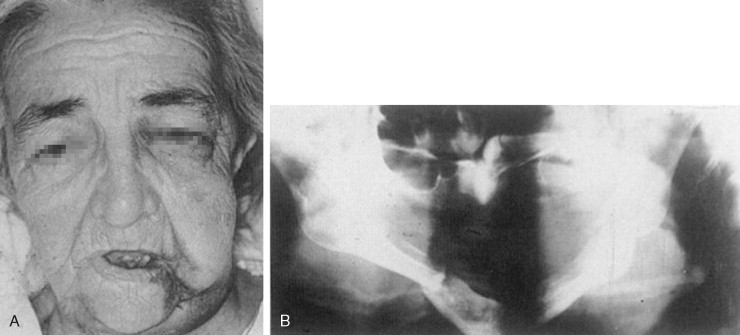

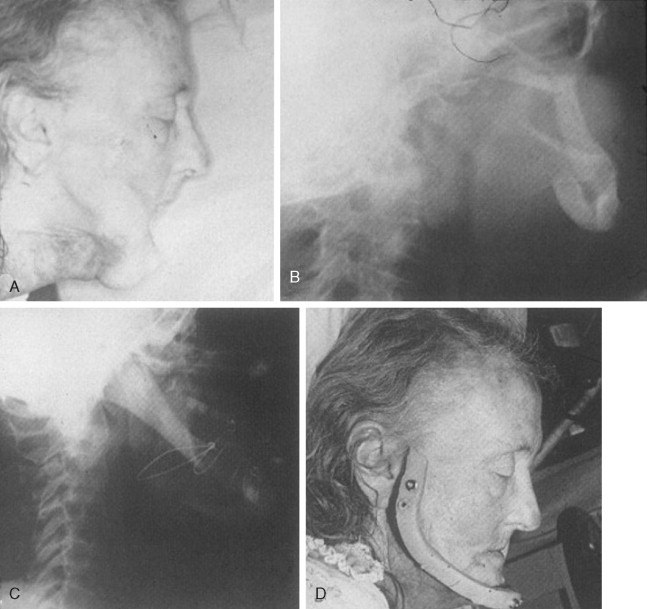

The impact of associated diseases on the etiology, course, and mortality in geriatric trauma patients was studied in a prospective and observational investigation of 55 patients aged over 65 years. Although not an essential factor in the cause per se, the diseases often encountered in the geriatric trauma population have a significant role on the recovery course and mortality. Trauma specialists must carefully consider a pre-accident neurologic or cardiovascular event when evaluating an elderly trauma victim that may have prompted the subsequent accident event and adversely affect definitive injury repair. Complex medical findings that encourage a compromised treatment plan to minimize peri-operative risks may be prudent and necessary ( Figure 22-7 ).

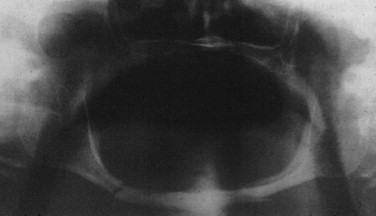

Withholding treatment of facial injuries or compromised treatment works well when no or modified surgical care is not likely to result in a substantial functional compromise ( Figure 22-8 ). Conversely, when withholding definitive facial fracture repair will contribute to loss of function and impact negatively on the patient’s health and well-being, then accepting substantial operative risks including death must be considered ( Figure 22-9 ).

Phase I: Accident Circumstances

-

Mechanism of injury

-

Immediate pre-injury events

-

Extirpation and on-scene resuscitation events

Phase II: Primary Survey

-

Predictors of respiratory distress

-

Life-threatening conditions identified and managed

Phase III: Secondary Survey

-

Time-consuming tests

-

Observations for the occult

-

Medical history

-

Stabilizing the patient

Phase IV: Stage 1 Treatment Planning

-

Optimize patient medically

-

Identify psychosocial issues

-

Identify societal issues

-

Begin discharge planning

Phase V: Stage 2 Treatment Planning Discharge Planning

-

Prioritize and integrate surgical treatments

-

Develop facial trauma surgical plan

-

Anticipate and prepare for postoperative events

Phase VI: Final Discharge Planning

-

Living circumstances

-

Financial circumstances

-

Societal considerations

-

Correcting adverse medical and psychosocial problems

Phase VII: Long-Term Rehabilitation

-

Facial injury and repair follow-up

-

Physical therapy needs

-

Return to gainful activities

-

Reducing society’s costs

-

Treating addictions

Pre-injury Health

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses