A young man, 19 years of age, with the chief complaint of an anterior open bite, came for orthodontic treatment with a skeletal Class I relationship, anterior open bite, shortened maxillary incisor roots, and relative macroglossia. The malocclusion was treated by extracting the maxillary first premolars and using a fixed edgewise appliance. A partial glossectomy was performed before the orthognathic surgery with a 3-piece segmental LeFort I mandibular setback, and advancement was achieved with a reduction genioplasty. A functional and esthetic occlusion with an improved facial profile was established, and the apex of the maxillary left central incisor became slightly rounded after prolonged and significant tooth movement. Four years after treatment, there was occlusal stability of the results, and no further root shortening was observed.

It is well accepted that tongue size and position affect skeletal and dental components. Macroglossia, or enlarged tongue, is thought to be an etiologic factor in open bite, bimaxillary protrusion, and dental arch spacing, and it might cause instability after orthodontic treatment. A partial glossectomy to reduce tongue size can be useful in treating these problems. Understanding the signs and symptoms of macroglossia will help to identify patients who could benefit from a reduction glossectomy to improve function, esthetics, and treatment stability.

True macroglossia occurs when the tongue size is truly abnormal, caused by either congenital or acquired factors, or when histologic abnormalities correlate with the clinical findings of tongue enlargement. Vascular malformations, muscular enlargement, and tumors are the most common forms of true macroglossia. Pseudomacroglossia, or relative macroglossia, is a condition in which the tongue can be normal in size but appears large relative to its anatomic interrelationships and includes cases of apparent tongue enlargement in which the histology does not provide a pathologic explanation.

There is no practical method of measuring tongue size, and it is sometimes difficult to evaluate the degree to which macroglossia is implicated in a malocclusion. Therefore, a clinical understanding of the signs and symptoms of macroglossia are important when planning orthodontic treatment and in predicting posttreatment stability. Tongue size should be judged by clinical appearance based on a discrepancy between the size of the tongue and that of the oral cavity. Macroglossia can also cause diastemas in the mandibular arch.

This article describes the treatment of a patient with an anterior open bite and shortened maxillary central incisor roots associated with relative macroglossia; he was treated with a partial glossectomy before orthognathic surgery. The long-term results are shown 4 years after appliance removal.

Diagnosis and etiology

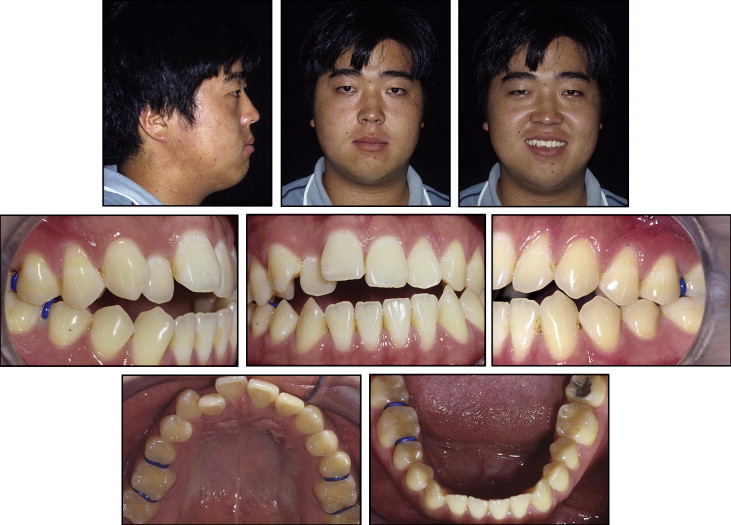

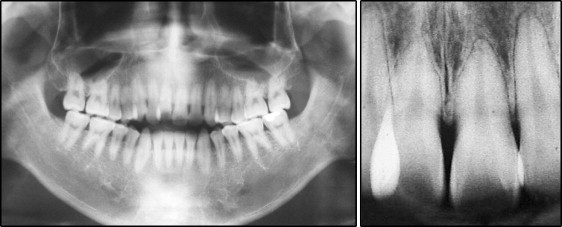

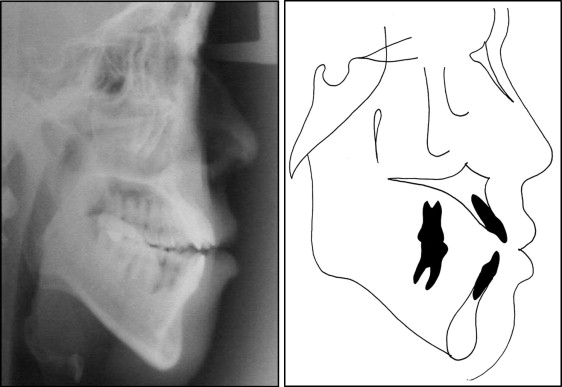

The patient was a 19-year-old man who came for orthodontic treatment with the chief complaint of an inability to bite on his front teeth. He had a long lower facial height, lack of lip seal, and slight facial asymmetry with the left side more rounded than the right. He had an Angle Class I malocclusion, anterior open bite, and occlusal contact only in the premolar and molar areas, with the maxillary midline shifted to the right. He had chronic posturing of the tongue between the anterior teeth ( Figs 1 and 2 ). The panoramic and periapical radiographs showed shortened roots of both maxillary central incisors ( Fig 3 ). The lateral cephalometric radiograph showed marked vertical discrepancy between the 2 jaws (FMA, 34°), skeletal Class I (ANB, 1°), proclined maxillary incisors (1.NA, 35°), and good mandibular incisor positioning (1.NB, 25°) ( Fig 4 , Table ).

| Measurement | Pretreatment | Posttreatment | Retention (4 y 2 mo) |

|---|---|---|---|

| SNA angle (°) | 76 | 80 | 81 |

| SNB angle (°) | 75 | 77 | 78 |

| ANB angle (°) | 1 | 3 | 3 |

| Convex angle (°) | 2 | 5 | 4 |

| Y-axis (°) | 66 | 63 | 62 |

| Facial angle (°) | 85 | 92 | 92 |

| GoGn-SN (°) | 45 | 38 | 37 |

| FMA (°) | 34 | 28 | 26 |

| IMPA (°) | 83 | 79 | 83 |

| 1-NA (°) | 35 | 23 | 22 |

| 1-NA (mm) | 12 | 2 | 2 |

| 1-NB (°) | 25 | 17 | 18 |

| 1-NB (mm) | 10 | 4 | 3 |

| Interincisal angle (°) | 120 | 137 | 138 |

| LS-S (mm) | 4 | 1 | 0 |

| LI-S (mm) | 6 | 1 | 0 |

| Z-angle (°) | 69 | 80 | 82 |

Treatment objectives and plan

The treatment goals were to (1) correct the open bite, (2) reduce the dental protrusion, (3) improve lip function, (4) reduce the size of the tongue for greater stability and appropriate function, (5) achieve better facial balance, and (6) maintain the root length.

The treatment consisted of extraction of the maxillary first premolars; alignment, leveling, and straightening the maxillary incisors; and surgery with maxillary posterior impaction by LeFort I osteotomy, mandibular setback, and reduction genioplasty. In the mandible, interproximal enamel reduction was performed. Before the orthodontic treatment, the patient and his parents were informed of the risk of further root shortening and possible loss of tooth stability.

Treatment objectives and plan

The treatment goals were to (1) correct the open bite, (2) reduce the dental protrusion, (3) improve lip function, (4) reduce the size of the tongue for greater stability and appropriate function, (5) achieve better facial balance, and (6) maintain the root length.

The treatment consisted of extraction of the maxillary first premolars; alignment, leveling, and straightening the maxillary incisors; and surgery with maxillary posterior impaction by LeFort I osteotomy, mandibular setback, and reduction genioplasty. In the mandible, interproximal enamel reduction was performed. Before the orthodontic treatment, the patient and his parents were informed of the risk of further root shortening and possible loss of tooth stability.

Treatment alternatives

Because of the severity of this patient’s malocclusion, a combination of orthodontic treatment and surgery was proposed as a favorable treatment option to achieve realistic treatment objectives, as suggested by Kokich. The second suggested option was to attempt to treat without surgery with molar intrusion using titanium screw anchorage to level and achieve normal overjet and overbite. When both options were discussed, the patient was explicitly told that it would be necessary to reduce the tongue size that was associated with the open bite, and that would be important for posttreatment stability. After discussing the treatment options, the patient and his parents chose the partial glossectomy before surgery, with the potential risks and complications associated with the procedure.

Treatment progress

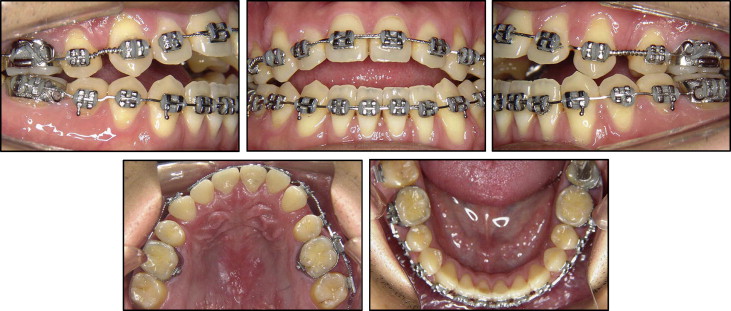

The maxillary premolar extraction spaces were closed using a fixed standard (0.022 × 0.028-in) edgewise appliance, but the anterior open bite began to worsen. Therefore, we decided to reopen and maintain the spaces between the canines and the second premolars to facilitate a 3-piece maxillary LeFort I osteotomy without damaging the roots ( Fig 5 ).