Chapter 16 Friedman tongue position and the staging of obstructive sleep apnea/hypopnea syndrome

1 INTRODUCTION

Obstructive sleep apnea/hypopnea syndrome (OSAHS) is often the result of obstruction at multiple anatomic sites. Nasal, palatal and hypopharyngeal obstruction, acting alone or in concert, are frequently identified as the cause of snoring and OSAHS. Even in cases where a single site is primarily involved, the increase in negative pressure may induce further obstruction in other areas. When surgical management of OSAHS is considered, a clear understanding of the complex relationship between the sites of obstruction is essential to surgical success.

The importance of determining the sites of obstruction has led to the development of numerous methods that attempt to predict the location of the upper airway obstruction. These include snoring sound analysis, physical examination, computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, cephalometric studies and fluoroscopy, among others. Although these methods have demonstrated value, the number of methods described is evidence of the lack of agreement that any single method is perfect. The most commonly used method is the Mueller maneuver (MM). Borowiecki and Sassin first described this maneuver for the preoperative assessment of sleep-disordered breathing (SDB).1 The MM consists of having the patient perform a forced inspiratory effort against an obstructed airway with fiberoptic endoscopic visualization of the upper airway. The test is widely used and simple to perform. Despite this, its use is controversial and certainly no studies have been able to associate the maneuver as a tool for patient selection. It is within this context that the Friedman tongue positions (FTP) emerged.

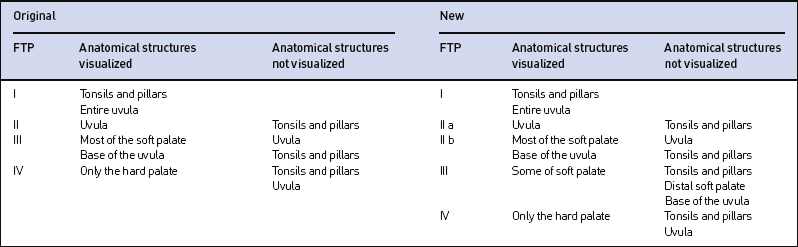

Initially presented by Friedman et al. in 1999,2 FTP (previously identified as the Mallampati palate position and subsequently as the Friedman palate position) has been found to be a simple method to approximate obstruction at the hypopharyngeal level. This classification is based on observations by Mallampati, who published a paper on palate position as an indicator of the ease or difficulty of endotracheal intubation by standard anesthesiologist techniques.3 The Mallampati stages had only been studied in the context of difficult intubations; therefore two major modifications were incorporated into FTP for its use in sleep medicine. First, the anesthesiologist assessment is based on the patient sticking out their tongue and the observer then noting the relationship of the soft palate to the tongue. FTP is based on evaluating the tongue in a neutral, natural position inside the mouth. Second, the Mallampati system had only three grades. Initially, FTP included four distinct positions, but we now believe that five positions are necessary to best describe the anatomy (Table 16.1). Due to these modifications and because this system describes the position of the tongue relative to the tonsils/pillar, uvula, soft palate, and hard palate, we have identified it as the Friedman tongue position (FTP). FTP has been studied extensively as it relates to OSAHS. As there are no studies that have been done on the ‘Mallampati position’ in sleep medicine, the use of the term is inaccurate in the context of OSAHS.

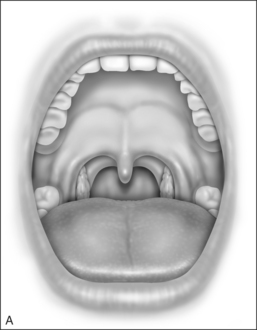

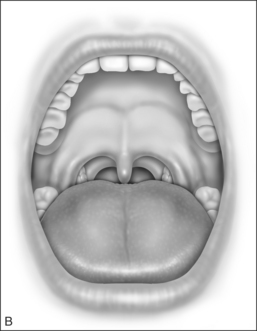

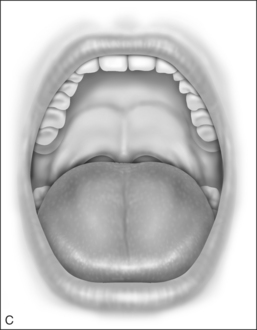

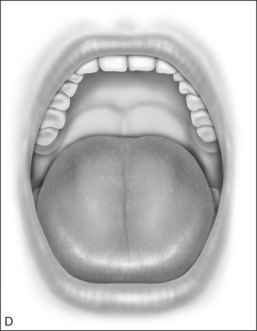

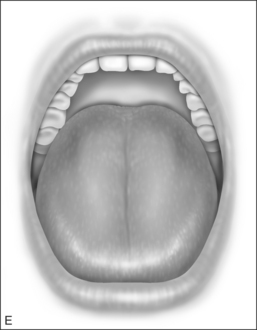

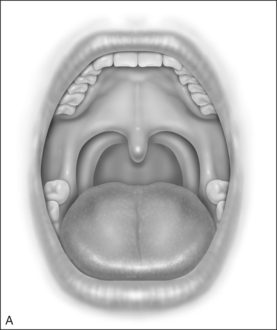

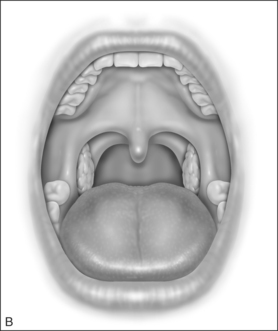

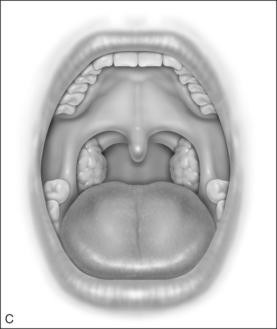

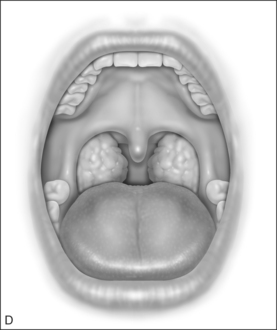

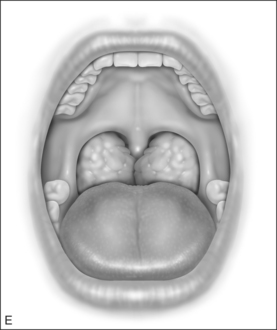

The procedure for identifying FTP involves asking the patient to open their mouth widely without protruding the tongue. The procedure is repeated five times so that the observer can assign the most consistent position as the FTP. FTP I allows the observer to visualize the entire uvula and tonsils or pillars (Fig. 16.1). FTP IIa allows visualization of the uvula but only parts of the tonsils are seen. FTP IIb allows visualization of the complete soft palate down to the base of the uvula, but the uvula and the tonsils are not seen. FTP III allows visualization of some of the soft palate but the distal soft palate is eclipsed. FTP IV allows visualization of the hard palate only (Fig. 16.1).

Earlier publications have described only four FTPs. In our experience with the system over the years, we have found that the previous staging system a majority of patients were classified as FTP III. With such a large number of subjects categorized into this one position we believe that it is clinically relevant to further stratify this group in terms of characteristics and response to surgical outcomes. We have found that expanding FTP II into two groups, FTP IIa and FTP IIb, provides the means for achieving this stratification. Patients with FTP IIb, although they may have been formerly classified as FTP III in the earlier staging system, share surgical response rates more characteristic of FTP II.

Once FTP is determined, the information can be incorporated into two distinct algorithms which can provide insights on the diagnosis and management of OSAHS. First, the use of FTP enables the clinician to predict the presence of OSAHS. A thorough history is most often the only screening for OSAHS. Unfortunately, many patients who are in denial about their symptoms cannot be identified by history alone, and therefore go undiagnosed. Routine use of FTP can be utilized as a cost-effective, non-invasive screening tool that will allow ready identification of patients that may suffer from OSAHS. Second, since FTP estimates the presence hypopharyngeal obstruction, determining FTP prior to surgical intervention can be instrumental in guiding the surgical management of OSAHS. Previous studies have demonstrated its ability to separate patients that will likely benefit from uvulopharyngopalatoplasty (UPPP) as a single modal treat-ment from those that will require multilevel surgical intervention.4,5

2 THE OSAHS SCORE

The estimated prevalence of OSAHS is 2% in women and 4% in men.6 There is also clear evidence that associates OSAHS with hypertension, insulin resistance, coronary heart disease, myocardial infarction and stroke, as well as compromised quality of life and significant social and emotional problems;7 yet it estimated that approximately 80% of cases remain undiagnosed.8 The primary screening for OSAHS is by a thorough history. Patients who complain of snoring, excessive daytime sleepiness or observed apnea are usually the only ones who are further tested for OSAHS. The major inaccuracy of such a screening system is that history, in the context of OSAHS, has a low sensitivity.The obstacles in eliciting history in sleep apnea patients are two-fold. First, because the patient is asleep when the pathology occurs, they are largely unaware of the problem and often deny symptoms. In such cases, only a history elicited from a bedpartner can offer sufficient insight into symptomology. Second, symptoms of OSAHS often overlap with other pathologies physical findings can help direct further testing. For example, a patient complaining of excessive sleepiness and fatigue may very likely receive a full work-up for depression and not OSAHS.

FTP can be employed in an algorithm that can help identify patients with OSAHS. This system is based on three readily identifiable and reproducible physical exam findings and can provide a simple means for screening patients. The system relies on calculating the patient’s Body Mass Index (BMI), along with the assessment of the patient’s tonsil size and FTP. FTP position is assessed according to the system stated in the previous section. Tonsil size and BMI are assessed as follows. Tonsil size is graded from 0 to 4. Tonsil size 1 implies tonsils hidden within the pillars. Tonsil size 2 implies the tonsil extending to the pillars. Size 3 tonsils are beyond the pillars but not to the midline. Tonsil size 4 implies tonsils that extend to the midline (Fig. 16.2).

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses