Foreign bodies in the ear, nose, and throat are commonly seen in family medicine, usually in children. Occasionally, orthodontic appliances or parts of orthodontic appliances are accidentally swallowed and have caused problems with either the airway or the gastrointestinal tract. The purposes of this article were to describe the type of appliances most likely to cause problems and to discuss their clinical management. The case of a patient who swallowed a key for turning fixed expansion appliances is presented. The key became lodged in the patient’s pharynx but subsequently passed through the gastrointestinal tract. Suggestions are made to prevent the problems that were encountered in this case and others reported in the literature in orthodontic patients.

Foreign bodies in the pharynx or trachea are medical emergencies. Successful removal depends on several factors, including location of the foreign body, type of material, whether the material is graspable (soft and irregular) or nongraspable (hard and spherical), the physician’s dexterity, and the patient’s cooperation. We report on a patient who accidentally swallowed the key used to activate a rapid maxillary expansion appliance.

Case report

A 17-year-old cleft palate patient was supine in a dental chair at our cleft clinic. We were opening the hyrax screw on his bonded splint when his cell phone rang. Startled, the patient moved his head; the key slipped and became lodged in his pharynx. He was immediately made to lie on one side and asked to cough forcefully. The dental chair was then adjusted to the upright position. The Heimlich maneuver was performed to expel the key, but it was of no use. The patient was immediately taken to the otorhinolaryngology emergency room in our hospital-based setup. A radiograph was done to localize the foreign body. The lateral view of the neck (in extended position) showed the key with its closed hexagonal loop facing downward (the head followed by the tail) in the region of the hypopharynx, overlapping the laryngeal shadow ( Fig 1 ). The patient was made to gargle with viscous lidocaine diluted 1:1 with water. Then an effort was made to retrieve the key with Magill’s forceps under the fiber-optic nasopharyngoscope. Because of the inconsistent grasp of the forceps and the patient’s spontaneous gag reflex, the key continued to slip downward. A lateral radiograph of the neck and posteroanterior view of the chest taken immediately showed clear fields ( Figs 2 and 3 ). Descent of the key into the left hypochondrium (stomach) was confirmed by an anteroposterior radiograph of the abdomen (in supine position) 2 hours after the incident ( Fig 4 ). In consultation with a gastroenterologist, an option at this stage was endoscopic retrieval of the key. However, since the patient had no symptoms of trauma or perforation, a conservative approach was preferred. He was sent home with a recall visit on the next day. Special instructions were given for the consumption of laxatives and monitoring of his stools.

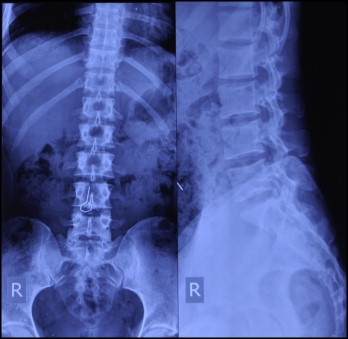

The next day, 18 hours after ingestion of the key, anteroposterior and lateral radiographs of abdomen were taken. The key was in the small bowel intestinal loop, overlying the L4 vertebral body ( Fig 5 ). The patient was sent home with the same instructions.

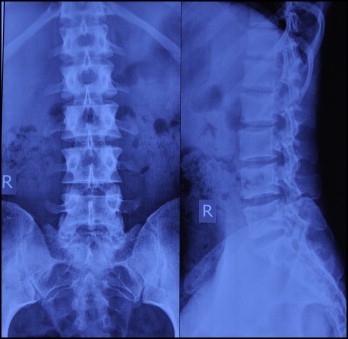

The next day, 42 hours after ingestion, anteroposterior and lateral radiographs of the abdomen were clear, suggesting that the key has been expelled ( Fig 6 ).

Discussion

Orthodontic appliances or parts of them can compromise the airway and gastrointestinal tract because of their close proximity to the oropharynx. Any foreign body in the airway needs to be treated as a serious situation, since it can be a cause of accidental death. Food materials constitute the majority of foreign bodies found in the airway, with the highest incidence occurring in childen younger than 3 years. Foreign bodies entering the alimentary canal do not represent a serious medical problem unless they become impacted or cause perforation of the gut wall; most pass through without incident.

The incidence of aspiration or swallowing of foreign bodies of dental origin varies considerably in the literature. However, aspiration or ingestion of orthodontic appliances is less common. There are literature reports of swallowing a transpalatal arch during its removal, a mandibular spring retainer, a maxillary removable appliance, a fragment of a maxillary removable appliance, a piece of archwire, and expansion appliance keys.

In the delivery of dental care, there has been a trend to treat patients in a supine position to aid in access to the oral cavity. In this position, there is an increased risk of objects entering the oropharynx. However, accidents are possible when treating patients in any position. The most readily visible site for entrapment of a foreign body that has been displaced in the oropharynx is the supratonsillar recess, followed by the epiglottic vallecula and the piriform recess. If the foreign body cannot be found in these places, it should be assumed that it has either been swallowed or aspirated.

If an object is dropped into the mouth in a supine patient, the patient’s head should be turned to one side to encourage the object to fall into the cheek and not the oropharynx, or the patient could be turned face down to allow the object to fall out of the mouth. The patient should be asked to cough. The mouth and oropharynx should be examined; if the object is visible, it should be removed with either forceps or high-speed suction, which should be available during all dental procedures.

Most foreign bodies entering the oropharynx go into the alimentary canal and pass without incident, although there is a danger of perforation of the gut, which can have serious consequences, including death. In the esophagus, only large objects and those with sharp edges are liable to become impacted; if this occurs, it is usually at the level of the fourth cervical vertebrae. Symptoms of esophageal obstruction are inability to swallow, muscle incoordination, pain on swallowing, hematemesis, or vomiting. Once a foreign body has reached the stomach, it has an 80% to 90% chance of passing through the gut without problems. Less than 1% of these foreign bodies have caused a perforation. The most common sites for perforation are the ileocecal junction and the sigmoid colon. The symptoms vary among abdominal pain, fever, nausea, vomiting, and abdominal distension, and diagnosis can be difficult. The usual time taken for a foreign body to traverse the intestinal tract is 2 to 12 days. If it is suspected that a patient has swallowed a foreign body, he or she should be referred to the appropriate medical specialty, because it might be necessary to electively remove an object with sharp edges to avoid perforation. On occasions, patients have been advised to supplement their diet with a large amount of cellulose, laxatives, and foods such as bananas, which theoretically aid the passage of the object through the gut. For radiolucent objects, ingestion of cotton wool pellets mixed with small amounts of barium-sulphate suspension has been reported to form a radiopaque bolus around the object, which allows it to be tracked through the gut radiographically.

The aspiration of a foreign body during dental treatment presents a serious problem, and the symptoms depend on where the object becomes impacted. If it is trapped above the vocal cords, acute respiratory distress can result; this requires urgent action. Smaller objects, however, tend to pass through the vocal cords, and upper airway obstruction does not occur. The commonest symptoms of laryngotracheal foreign bodies are dyspnea, cough, and stridor; those of bronchial foreign bodies are cough, decreased air entry, dyspnea, and wheezing. Hoarseness will accompany obstruction of the larynx or trachea with or without cyanosis depending on whether the obstruction is partial or complete. Initial symptoms can subside, and small foreign bodies might have no initial effects and go unrecognized until later, when secondary symptoms such as pneumonia develop. Symptoms of aspiration can also be overlooked when the patient has a history of asthma or the history of inhalation is obscure. Foreign bodies that have been present for some time can cause abscess formation, pneumonia, atelectasis, or bronchiectasis, and their removal can be complicated by granulation or scar tissue.

Management of aspirated foreign bodies depends on the severity of the symptoms. If the foreign body is obstructive and the patient is in respiratory distress, dislodgement of the foreign body should be initially attempted with back blows and the Heimlich maneuver. If these fail to dislodge the object, positive airway pressure needs to be maintained by artificial respiration; if this fails to maintain a patent airway, the object should be bypassed, and an emergency airway established. The approach recommended is via the cricothyroid membrane and should be attempted only by a medical practitioner with the appropriate training. Once an airway has been established, the patient should be transferred to a hospital for emergency medical attention. If the object has passed the vocal cords and there is no obstruction of the airway, the patient should still be referred for immediate medical attention. All foreign objects in the respiratory tract need to be removed, and this should be done as soon as possible because edema, excessive secretions, and formation of granulation tissue can make localization and removal difficult. The mucosal appearance of the pink acrylic often used in orthodontics can also make visualization during bronchoscopy of any fragment of inhaled acrylic difficult and, hence, might complicate its removal. Although spontaneous expectoration of inhaled foreign bodies occurs in 1% to 2% of cases, waiting for this to happen with postural drainage is no longer recommended because, if the foreign body is dislodged from its original location, it can obstruct the airway.

Clinical recommendations

Appliances or their components can become dislodged if retention is inadequate, and potentially serious complications to the larynx, pharynx, or gastrointestinal tract can arise. Problems have been caused by a variety of appliances, and the following recommendations are derived from this case report and those of other authors.

- 1.

Cell phones should be turned off in the clinic, where they can distract patients, the orthodontist, and the staff.

- 2.

When adjusting small components intraorally, place a gauze dental napkin behind the orthodontic appliance to act as a barrier.

- 3.

Tie floss leashes onto expansion keys, transpalatal arches, quad-helices, molar bands, and any other loose components when adjusting them intraorally. Keys attached to a plastic ring holder are commercially available.

- 4.

Use wax to temporarily stabilize auxiliaries, such as coil springs, on archwires.

- 5.

Use acrylics in colors other than pink to construct removable appliances and retainers. Removable appliances should be suitably retentive and of an adequate size. Avoid sharp edges and hooked or pointed wire components. Check the appliances regularly.

- 6.

Consider radiopaque acrylic for clear orthodontic appliances; however, these materials might possess compromised strength and esthetics.

- 7.

Advise patients both verbally and with written instructions at appliance placement that they should not try to reinsert damaged, ill-fitting, or broken fragments of any appliance. They should stop using them immediately until the appliance is checked.

- 8.

Select archwire material and grade not only for the forces required to move teeth, but also for the wire’s ability to withstand masticatory stresses.

- 9.

Before cutting the ends of archwires intraorally with safety distal-end wire cutters, place a cotton roll over the end of the archwire.

- 10.

Regularly inspect all orthodontic instruments for signs of failure; replace or recondition these instruments on a regular basis.

- 11.

When taking impressions, use a material with high viscosity and trays that fit properly. An upright position for the patient is recommended with clear instructions. The clinician should be able to visualize the back of the upper tray as it is seated in the mouth so that excess impression material does not extrude into the back of the mouth. The patient should then be advised to tilt the head forward, chin down, and avoid swallowing. Provide a bib or towel. Patients might find it more comfortable to breath through their mouth, rather than their nose, while the impression is seated in the mouth.

- 12.

If a piece of appliance is dropped in the mouth during treatment, high-speed suction with a pharyngeal tip can help with quick retrieval.

- 13.

In cases of respiratory distress resulting from aspiration of an object, the Heimlich maneuver is recommended. If the patient is in severe distress, maintain positive air pressure with cardiopulmonary resuscitation until medical help arrives. Keep up to date with cardiopulmonary resuscitation, since the recommendations can change.

- 14.

Immediate attention and elective intervention as suggested by medical consultants should be done to prevent the risk of perforation.

The authors report no commercial, proprietary, or financial interest in the products or companies described in this article.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses