This case report describes the treatment of a 9-year old boy, who had his maxillary central incisors extruded by noncontrolled elastic mechanics to close a diastema. The article describes the consequences of this movement and how the problem was solved with controlled intrusion.

Broadbent first described the “ugly duckling stage” of dental development in the literature. Proffit and Fields reported that this stage is characterized by diastemas in the maxillary arch. The central diastema tends to close as the lateral incisors erupt, but the diastema can persist even after eruption is complete. This situation occurs so frequently that it is considered normal. For this reason, the mixed dentition can be a difficult time for children, their parents, and the orthodontist; as the child’s permanent teeth erupt, his or her smile is not as esthetic as it was during the deciduous dentition. Parents often worry about dental spacing, and the orthodontist must explain that this unesthetic period is normal and is not to be treated at that time.

Unfortunately, not every dentist is familiar with this stage and the correct way to handle the situation; as a result, the patient can suffer the consequences. This case report describes this type of situation and the orthodontic treatment necessary to overcome a serious problem.

Diagnosis and etiology

A 9-year-old boy came to the orthodontic clinic at Rio de Janeiro State University in Brazil complaining that his maxillary central incisors were extruded. He had a straight profile and good facial proportions. The clinical examination showed that he was in the mixed dentition, with a Class I molar relationship and crossbite of the maxillary lateral incisors, the right deciduous canine, and the right deciduous first molar. The midline was shifted 2 mm to the left in both arches. There was an overjet of 3 mm and a mild curve of Spee.

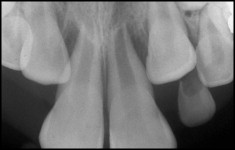

But the most significant anomaly was the extreme extrusion of the maxillary central incisors with advanced gingival recession around these teeth ( Fig 1 ). His mother mentioned that he previously had a wide gap between those teeth, and she took him to a dentist who recommended placing a rubber band around the 2 teeth to close this space. The elastic disappeared every night, and the dentist told him to put another in its place. The mother suspected that something was not right and decided to ask for a second opinion.

At this point, the central incisors had extruded about 6 mm and were extremely mobile. He had gingival hyperplasia, bleeding on probing, and deep pockets around the incisors. The elastics kept disappearing, because they were sliding up along the periodontal ligament space and gradually extracting the teeth. A panoramic radiograph showed the presence of all permanent teeth. An anterior periapical radiograph showed significant loss of bone around the central incisors, and the roots of the central incisors were in contact ( Fig 2 ).

Treatment objectives

The long-term prognosis for the central incisors was poor, but we decided to maintain these teeth as long as possible. So, the treatment objectives at this first stage were to remove the elastics from beneath the gingiva, intrude the central incisors, and align their roots to improve the bone support in this area.

Treatment objectives

The long-term prognosis for the central incisors was poor, but we decided to maintain these teeth as long as possible. So, the treatment objectives at this first stage were to remove the elastics from beneath the gingiva, intrude the central incisors, and align their roots to improve the bone support in this area.

Treatment progress

The central incisors were splinted, and a surgical procedure was used to remove the elastics ( Fig 3 ). When the flap was elevated, the bone loss, mainly on the facial side, was evident. During surgery, no scaling was performed on the roots to maintain any remnants of the periodontal ligament. Only superficial cleaning was performed to avoid damaging the cementum and, we hoped, allow future replacement of the fibers of the periodontal ligament. The inflammatory tissue was removed, and the flap was repositioned. A rigid oral hygiene program was adopted.

When the periodontal health had improved, brackets were bonded to the 2 central incisors, and bands were cemented on the maxillary first molars. A utility 0.019 × 0.025-in stainless steel archwire was used to intrude the incisors. After 6 months, both central incisors had been intruded to normal positions, and their mobility had decreased significantly. However, the roots were still in close proximity. At that time, we stopped the intrusion mechanics and placed another segmented 0.019 × 0.025-in archwire on the central incisors with small artistic bends to tip the roots distally and create space between them ( Fig 4 ). Two months later, the radiograph showed a small space between the roots with bone formation in the area ( Fig 5 ).